Anarchist Theorizing and Organizing in Edmonton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After Makhno – Hidden Histories of Anarchism in the Ukraine

AFTER MAKHNO The Anarchist underground in the Ukraine AFTER MAKHNO in the 1920s and 1930s: Outlines of history By Anatoly V. Dubovik & The Story of a Leaflet and the Pate of SflHflMTbl BGAVT3AC060M the Anarchist Varshavskiy (From the History of Anarchist Resistance to nPM3PflK CTflPOPO CTPOJI Totalitarianism) "by D.I. Rublyov Translated by Szarapow Nestor Makhno, the great Ukranian anarchist peasant rebel escaped over the border to Romania in August 1921. He would never return, but the struggle between Makhnovists and Bolsheviks carried on until the mid-1920s. In the cities, too, underground anarchist networks kept alive the idea of stateless socialism and opposition to the party state. New research printed here shows the extent of anarchist opposition to Bolshevik rule in the Ukraine in the 1920s and 1930s. Cover: 1921 Soviet poster saying "the bandits bring with them a ghost of old regime. Everyone struggle with banditry!" While the tsarist policeman is off-topic here (but typical of Bolshevik propaganda in lumping all their enemies together), the "bandit" probably looks similar to many makhnovists. Anarchists in the Gulag, Prison and Exile Project BCGHABOPbBV Kate Sharpley Library BM Hurricane, London, WC1N 3 XX. UK C BftHflMTMSMOM! PMB 820, 2425 Channing Way, Berkeley CA 94704, USA www.katesharpleylibrary.net Hidden histories of Anarchism in the Ukraine ISBN 9781873605844 Anarchist Sources #12 AFTER MAKHNO The Anarchist underground in the Ukraine in the 1920s and 1930s: Outlines of history By Anatoly V. Dubovik & The Story of a Leaflet and the Pate of the Anarchist Varshavskiy (From the History of Anarchist Resistance to Totalitarianism) "by D.I. -

The Continuum Companion to Anarchism

The Continuum Companion to Anarchism 9781441172129_Pre_Final_txt_print.indd i 6/9/2001 3:18:11 PM The Continuum Companion to Anarchism Edited by Ruth Kinna 9781441172129_Pre_Final_txt_print.indd iii 6/9/2001 3:18:13 PM Continuum International Publishing Group The Tower Building 80 Maiden Lane 11 York Road Suite 704 London SE1 7NX New York, NY 10038 www.continuumbooks.com © Ruth Kinna and Contributors, 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitt ed, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the permission of the publishers. E ISBN: 978-1-4411-4270-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record of this title is available from the Library of Congress. Typeset by Newgen Imaging Systems Pvt Ltd, Chennai, India Printed and bound in the United States of America 9781441172129_Pre_Final_txt_print.indd iv 6/9/2001 3:18:13 PM Contents Contributors viii Acknowledgements xiv Part I – Research on Anarchism 1 Introduction 3 Ruth Kinna Part II – Approaches to Anarchist Research 2 Research Methods and Problems: Postanarchism 41 Saul Newman 3 Anarchism and Analytic Philosophy 50 Benjamin Franks 4 Anarchism and Art History: Methodologies of Insurrection 72 Allan Antliff 5 Participant Observation 86 Uri Gordon 6 Anarchy, Anarchism and International Relations 96 Alex Prichard Part III – Current Research in Anarchist Studies 7 Bridging the Gaps: Twentieth-Century Anglo-American Anarchist Thought 111 Carissa Honeywell 8 The Hitchhiker as Theorist: Rethinking Sociology and Anthropology from an Anarchist Perspective 140 Jonathan Purkis 9 Genders and Sexualities in Anarchist Movements 162 Sandra Jeppesen and Holly Nazar v 9781441172129_Pre_Final_txt_print.indd v 6/9/2001 3:18:13 PM Contents 10 Literature and Anarchism 192 David Goodway 11 Anarchism and the Future of Revolution 212 Laurence Davis 12 Social Ecology 233 Andy Price 1 3 Leyendo el anarchismo a través de ojos latinoamericanos : Reading Anarchism through Latin American Eyes 252 Sara C. -

The State and Revolution: Theory and Practice Contents

The State and Revolution: Theory and Practice Iain McKay This is almost my chapter in the anthology Bloodstained: One Hundred Years of Leninist Counterrrevolution (Oakland/Edinburgh: AK Press, 2017). Some revisions were made during the editing process which are not included here. In addition, references to the 1913 French edition of Kropotkin’s Modern Science and Anarchy have been replaced with those from the 2018 English-language translation. However, the bulk of the text is the same, as is the message and its call to learn from history rather than repeat it. I would, of course, urge you to buy the book. Contents The State and Revolution: Theory and Practice ......................................................... 2 Theory .................................................................................................................... 2 The Paris Commune ........................................................................................... 4 Opportunism ....................................................................................................... 7 Anarchism ......................................................................................................... 10 Socialism ........................................................................................................... 18 The Party .......................................................................................................... 20 Practice ................................................................................................................ -

Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction.....................................................................................................................2 2. The Principles of Anarchism, Lucy Parsons....................................................................3 3. Anarchism and the Black Revolution, Lorenzo Komboa’Ervin......................................10 4. Beyond Nationalism, But not Without it, Ashanti Alston...............................................72 5. Anarchy Can’t Fight Alone, Kuwasi Balagoon...............................................................76 6. Anarchism’s Future in Africa, Sam Mbah......................................................................80 7. Domingo Passos: The Brazilian Bakunin.......................................................................86 8. Where Do We Go From Here, Michael Kimble..............................................................89 9. Senzala or Quilombo: Reflections on APOC and the fate of Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio...........................................................................................................................91 10. Interview: Afro-Colombian Anarchist David López Rodríguez, Lisa Manzanilla & Bran- don King........................................................................................................................96 11. 1996: Ballot or the Bullet: The Strengths and Weaknesses of the Electoral Process in the U.S. and its relation to Black political power today, Greg Jackson......................100 12. The Incomprehensible -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Burn It Down! Anarchism, Activism, and the Vancouver Five, 1967–1985

Burn it Down! Anarchism, Activism, and the Vancouver Five, 1967–1985 by Eryk Martin M.A., University of Victoria, 2008 B.A. (Hons.), University of Victoria, 2006 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Eryk Martin 2016 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2016 Approval Name: Eryk Martin Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (History) Title: Burn it Down! Anarchism, Activism, and the Vancouver Five, 1967–1985 Examining Committee: Chair: Dimitris Krallis Associate Professor Mark Leier Senior Supervisor Professor Karen Ferguson Supervisor Professor Roxanne Panchasi Supervisor Associate Professor Lara Campbell Internal Examiner Professor Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Joan Sangster External Examiner Professor Gender and Women’s Studies Trent University Date Defended/Approved: January 15, 2016 ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract This dissertation investigates the experiences of five Canadian anarchists commonly knoWn as the Vancouver Five, Who came together in the early 1980s to destroy a BC Hydro power station in Qualicum Beach, bomb a Toronto factory that Was building parts for American cruise missiles, and assist in the firebombing of pornography stores in Vancouver. It uses these events in order to analyze the development and transformation of anarchist activism between 1967 and 1985. Focusing closely on anarchist ideas, tactics, and political projects, it explores the resurgence of anarchism as a vibrant form of leftWing activism in the late tWentieth century. In addressing the ideological basis and contested cultural meanings of armed struggle, it uncovers Why and how the Vancouver Five transformed themselves into an underground, clandestine force. -

Yalensky's Fable: a History of the Anarchist Black Cross

Yalensky’s Fable: A History of the Anarchist Black Cross Matthew Hart 2003 Contents Propaganda by the Deed .................................. 5 Russian Revolution and the Continued Repression .................... 5 World War II ......................................... 6 The Second Wave ...................................... 7 The Present Wave ...................................... 8 Work Cited .......................................... 9 2 For close to a century, anarchists have united under the banner of the Anarchist Black Cross for the sole purpose of supporting those comrades imprisoned for their commitment to revolu- tion and to the ideas of anarchism. Who would have suspected that a few men supplying boots, linen, and clothing to deportees in Bialostock would have been the meager beginnings of an organization that has spread throughout the globe?1 Recently statements have been made, referring to the history of the Anarchist Black Cross as mere folklore. While I admit the history of this organization seems evasive at the surface level, a deeper search for the organization’s history uncovers a rich amount of information that is far from folklore or fairy tales. This article is just a small amount of the history that hasbeen discovered in just a couple of years of research. Hundreds of pages filled with facts regarding the history of the organization is presently being assembled by members of the Los Angeles Branch Group of the Anarchist Black Cross Federation in hopes of one day printing this information in books, pamphlets, etc. We present the informa- tion in hopes of bringing unity and knowledge within the ranks of those who struggle for the support of political prisoners throughout the world. The Anarchist Black Cross dates back to the beginning of the last century during the politically turbulent times of Tsarist Russia. -

Download As a PDF File

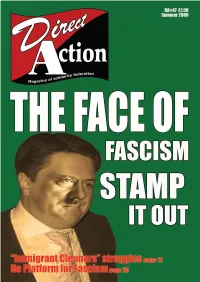

Direct Action www.direct-action.org.uk Summer 2009 Direct Action is published by the Aims of the Solidarity Federation Solidarity Federation, the British section of the International Workers he Solidarity Federation is an organi- isation in all spheres of life that conscious- Association (IWA). Tsation of workers which seeks to ly parallel those of the society we wish to destroy capitalism and the state. create; that is, organisation based on DA is edited & laid out by the DA Col- Capitalism because it exploits, oppresses mutual aid, voluntary cooperation, direct lective & printed by Clydeside Press and kills people, and wrecks the environ- democracy, and opposed to domination ([email protected]). ment for profit worldwide. The state and exploitation in all forms. We are com- Views stated in these pages are not because it can only maintain hierarchy and mitted to building a new society within necessarily those of the Direct privelege for the classes who control it and the shell of the old in both our workplaces Action Collective or the Solidarity their servants; it cannot be used to fight and the wider community. Unless we Federation. the oppression and exploitation that are organise in this way, politicians – some We do not publish contributors’ the consequences of hierarchy and source claiming to be revolutionary – will be able names. Please contact us if you want of privilege. In their place we want a socie- to exploit us for their own ends. to know more. ty based on workers’ self-management, The Solidarity Federation consists of locals solidarity, mutual aid and libertarian com- which support the formation of future rev- munism. -

Black Flag White Masks: Anti-Racism and Anarchist Historiography

Black Flag White Masks: Anti-Racism and Anarchist Historiography Süreyyya Evren1 Abstract Dominant histories of anarchism rely on a historical framework that ill fits anarchism. Mainstream anarchist historiography is not only blind to non-Western elements of historical anarchism, it also misses the very nature of fin de siècle world radicalism and the contexts in which activists and movements flourished. Instead of being interested in the network of (anarchist) radicalism (worldwide), political historiography has built a linear narrative which begins from a particular geographical and cultural framework, driven by the great ideas of a few father figures and marked by decisive moments that subsequently frame the historical compart- mentalization of the past. Today, colonialism/anti-colonialism and imperialism/anti-imperialism both hold a secondary place in contemporary anarchist studies. This is strange considering the importance of these issues in world political history. And the neglect allows us to speculate on the ways in which the priorities might change if Eurocentric anarchist histories were challenged. This piece aims to discuss Eurocentrism imposed upon the anarchist past in the form of histories of anarchism. What would be the consequences of one such attempt, and how can we reimagine the anarchist past after such a critique? Introduction Black Flag White Masks refers to the famous Frantz Fanon book, Black Skin White Masks, a classic in anti-colonial studies, and it also refers to hidden racial issues in the history of the black flag (i.e., anarchism). Could there be hidden ethnic hierarchies in the main logic of anarchism's histories? The huge difference between the anarchist past and the histories of anarchism creates the gap here. -

The History and Philosophy of the Postwar American Counterculture

The History and Philosophy of the Postwar American Counterculture: Anarchy, the Beats and the Psychedelic Transformation of Consciousness By Ed D’Angelo Copyright © Ed D’Angelo 2019 A much shortened version of this paper appeared as “Anarchism and the Beats” in The Philosophy of the Beats, edited by Sharin Elkholy and published by University Press of Kentucky in 2012. 1 The postwar American counterculture was established by a small circle of so- called “beat” poets located primarily in New York and San Francisco in the late 1940s and 1950s. Were it not for the beats of the early postwar years there would have been no “hippies” in the 1960s. And in spite of the apparent differences between the hippies and the “punks,” were it not for the hippies and the beats, there would have been no punks in the 1970s or 80s, either. The beats not only anticipated nearly every aspect of hippy culture in the late 1940s and 1950s, but many of those who led the hippy movement in the 1960s such as Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg were themselves beat poets. By the 1970s Allen Ginsberg could be found with such icons of the early punk movement as Patty Smith and the Clash. The beat poet William Burroughs was a punk before there were “punks,” and was much loved by punks when there were. The beat poets, therefore, helped shape the culture of generations of Americans who grew up in the postwar years. But rarely if ever has the philosophy of the postwar American counterculture been seriously studied by philosophers. -

Brill's Companion to Anarchism and Philosophy

Brill’s Companion to Anarchism and Philosophy Edited by Nathan Jun LEIDEN | BOSTON For use by the Author only | © 2018 Koninklijke Brill NV Contents Editor’s Preface ix Acknowledgments xix About the Contributors xx Anarchism and Philosophy: A Critical Introduction 1 Nathan Jun 1 Anarchism and Aesthetics 39 Allan Antliff 2 Anarchism and Liberalism 51 Bruce Buchan 3 Anarchism and Markets 81 Kevin Carson 4 Anarchism and Religion 120 Alexandre Christoyannopoulos and Lara Apps 5 Anarchism and Pacifism 152 Andrew Fiala 6 Anarchism and Moral Philosophy 171 Benjamin Franks 7 Anarchism and Nationalism 196 Uri Gordon 8 Anarchism and Sexuality 216 Sandra Jeppesen and Holly Nazar 9 Anarchism and Feminism 253 Ruth Kinna For use by the Author only | © 2018 Koninklijke Brill NV viii CONTENTS 10 Anarchism and Libertarianism 285 Roderick T. Long 11 Anarchism, Poststructuralism, and Contemporary European Philosophy 318 Todd May 12 Anarchism and Analytic Philosophy 341 Paul McLaughlin 13 Anarchism and Environmental Philosophy 369 Brian Morris 14 Anarchism and Psychoanalysis 401 Saul Newman 15 Anarchism and Nineteenth-Century European Philosophy 434 Pablo Abufom Silva and Alex Prichard 16 Anarchism and Nineteenth-Century American Political Thought 454 Crispin Sartwell 17 Anarchism and Phenomenology 484 Joeri Schrijvers 18 Anarchism and Marxism 505 Lucien van der Walt 19 Anarchism and Existentialism 559 Shane Wahl Index of Proper Names 583 For use by the Author only | © 2018 Koninklijke Brill NV CHAPTER 10 Anarchism and Libertarianism Roderick T. Long Introduction -

Debating Power and Revolution in Anarchism, Black Flame and Historical Marxism 1

Detailed reply to International Socialism: debating power and revolution in anarchism, Black Flame and 1 historical Marxism 7 April 2011 Source: http://lucienvanderwalt.blogspot.com/2011/02/anarchism-black-flame-marxism-and- ist.html Lucien van der Walt, Sociology, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, [email protected] **This paper substantially expands arguments I published as “Counterpower, Participatory Democracy, Revolutionary Defence: debating Black Flame, revolutionary anarchism and historical Marxism,” International Socialism: a quarterly journal of socialist theory, no. 130, pp. 193-207. http://www.isj.org.uk/index.php4?id=729&issue=130 The growth of a significant anarchist and syndicalist2 presence in unions, in the larger anti-capitalist milieu, and in semi-industrial countries, has increasingly drawn the attention of the Marxist press. International Socialism carried several interesting pieces on the subject in 2010: Paul Blackledge’s “Marxism and Anarchism” (issue 125), Ian Birchall’s “Another Side of Anarchism” (issue 127), and Leo Zeilig’s review of Michael Schmidt and my book Black Flame: the revolutionary class politics of anarchism and syndicalism (also issue 127).3 In Black Flame, besides 1 I would like to thank Shawn Hattingh, Ian Bekker, Iain McKay and Wayne Price for feedback on an earlier draft. 2 I use the term “syndicalist” in its correct (as opposed to its pejorative) sense to refer to the revolutionary trade unionism that seeks to combine daily struggles with a revolutionary project i.e., in which unions are to play a decisive role in the overthrow of capitalism and the state by organizing the seizure and self-management of the means of production.