Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

Introduction Other Voices: Dissenting Women Mary Franklin (d. 1711) was the wife of the Reverend Robert Franklin (1630–1703), one of some two thousand Nonconformist ministers who were “ejected” from their pulpits and their livings on Black Bartholomew’s Day,1 August 24, 1662, following the Restoration of Charles II (1630–1685). In May 1660, Charles returned from exile in Europe, beginning the Restoration of the monarchy. He was crowned on April 23, 1661. Though for many English subjects the Restoration was a joyous occasion, for the Dissenters,2 and especially for ministers and their relations, these became times that tried their souls. Mary Franklin wrote a narrative of her experi- ence of these times, taking up, late in life, one of her husband’s incomplete sermon notebooks, turning it upside down, and using its blank pages for her purposes.3 She wrote about her life as a minister’s wife and her family’s suffering under a govern- ment that exacted religious conformity to the Church of England as a measure of loyalty to the crown. She also recorded the triumph of God’s providences through it all. She did not seek publication of her brief, detailed, and moving testimony but rather seems to have kept the notebook within her family until her death, after 1. The name Black Bartholomew’s Day harkens back to a day of infamy for the Protestant godly, St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre, August 24, 1572, when tens of thousands of French Huguenots (Calvinists) were slaughtered by the Catholic King Charles IX. See N. -

America's Gothic Fiction

America’s Gothic Fiction America’s Gothic Fiction The Legacy of Magnalia Christi Americana Dorothy Z. Baker The Ohio State University Press Columbus Copyright © 2007 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Baker, Dorothy Zayatz. America’s gothic fiction : the legacy of Magnalia Christi Americana / Dorothy Z. Baker. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN-13: 978–0–8142–1060–4 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978–0–8142–9144–3 (cd-rom) 1. American fiction—History and criticism. 2. Religion and literature. 3. Mather, Cotton, 1663–1728. Magnalia Christi Americana. 4. Mather, Cotton, 1663–1728— Influence. 5. Puritan movements in literature. 6. Horror tales, American—History and criticism. 7. Gothic revival (Literature)—United States. 8. Religion and litera- ture—United States—History. 9. National characteristics, American, in literature. I. Title. PS166.B35 2007 813.’0872—dc22 2007012212 Cover design by Fulcrum Design Corps, LLC Text design and typesetting by Juliet Williams Type set in Minion Pro Printed by Thomson-Shore The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents w Acknowledgments vii Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 “We have seen Strange things to Day”: The History and Artistry of Cotton Mather’s Remarkables 14 Chapter 3 “A Wilderness of Error”: Edgar Allan Poe’s Revision of Providential Tropes 37 Chapter 4 Cotton Mather as the “old New England grandmother”: Harriet Beecher Stowe and the Female Historian 65 Chapter 5 Nathaniel Hawthorne and the “Singular Mind” of Cotton Mather 87 Chapter 6 “The story was in the gaps”: Catharine Maria Sedgwick and Edith Wharton 119 Works Cited 145 Index 157 Acknowledgments w My work on the legacy of Cotton Mather owes an immense debt to many scholars whose studies on American historical narrative and American his- torical fiction provided the foundation for this book. -

H Bavinck Preface Synopsis

University of Groningen Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae van den Belt, Hendrik; de Vries-van Uden, Mathilde Published in: The Bavinck review IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2017 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): van den Belt, H., & de Vries-van Uden, M., (TRANS.) (2017). Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae. The Bavinck review, 8, 101-114. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 24-09-2021 BAVINCK REVIEW 8 (2017): 101–114 Herman Bavinck’s Preface to the Synopsis Purioris Theologiae Henk van den Belt and Mathilde de Vries-van Uden* Introduction to Bavinck’s Preface On the 10th of June 1880, one day after his promotion on the ethics of Zwingli, Herman Bavinck wrote the following in his journal: “And so everything passes by and the whole period as a student lies behind me. -

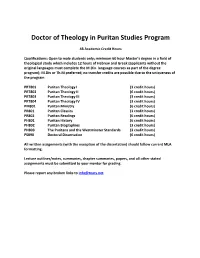

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program

Doctor of Theology in Puritan Studies Program 48 Academic Credit Hours Qualifications: Open to male students only; minimum 60 hour Master’s degree in a field of theological study which includes 12 hours of Hebrew and Greek (applicants without the original languages must complete the M.Div. language courses as part of the degree program); M.Div or Th.M preferred; no transfer credits are possible due to the uniqueness of the program. PRT801 Puritan Theology I (3 credit hours) PRT802 Puritan Theology II (6 credit hours) PRT803 Puritan Theology III (3 credit hours) PRT804 Puritan Theology IV (3 credit hours) PM801 Puritan Ministry (6 credit hours) PR801 Puritan Classics (3 credit hours) PR802 Puritan Readings (6 credit hours) PH801 Puritan History (6 credit hours) PH802 Puritan Biographies (3 credit hours) PH803 The Puritans and the Westminster Standards (3 credit hours) PS890 Doctoral Dissertation (6 credit hours) All written assignments (with the exception of the dissertation) should follow current MLA formatting. Lecture outlines/notes, summaries, chapter summaries, papers, and all other stated assignments must be submitted to your mentor for grading. Please report any broken links to [email protected]. PRT801 PURITAN THEOLOGY I: (3 credit hours) Listen, outline, and take notes on the following lectures: Who were the Puritans? – Dr. Don Kistler [37min] Introduction to the Puritans – Stuart Olyott [59min] Introduction and Overview of the Puritans – Dr. Matthew McMahon [60min] English Puritan Theology: Puritan Identity – Dr. J.I. Packer [79] Lessons from the Puritans – Ian Murray [61min] What I have Learned from the Puritans – Mark Dever [75min] John Owen on God – Dr. -

The Percival J. Baldwin Puritan Collection

The Percival J. Baldwin Puritan Collection Accessing the Collection: 1. Anyone wishing to use this collection for research purposes should complete a “Request for Restricted Materials” form which is available at the Circulation desk in the Library. 2. The materials may not be taken from the Library. 3. Only pencils and paper may be used while consulting the collection. 4. Photocopying and tracing of the materials are not permitted. Classification Books are arranged by author, then title. There will usually be four elements in the call number: the name of the collection, a cutter number for the author, a cutter number for the title, and the date. Where there is no author, the cutter will be A0 to indicate this, to keep filing in order. Other irregularities are demonstrated in examples which follow. BldwnA <-- name of collection H683 <-- cutter for author O976 <-- cutter for title 1835 <-- date of publication Example. A book by the author Thomas Boston, 1677-1732, entitled, Human nature in its fourfold state, published in 1812. BldwnA B677 <-- cutter for author H852 <-- cutter for title 1812 <-- date of publication Variations in classification scheme for Baldwin Puritan collection Anonymous works: BldwnA A0 <---- Indicates no author G363 <---- Indicates title 1576 <---- Date Bibles: BldwnA B524 <---- Bible G363 <---- Geneva 1576 <---- Date Biographies: BldwnA H683 <---- cuttered on subject's name Z5 <---- Z5 indicates biography R633Li <---- cuttered on author's name, 1863 then first two letters of title Letters: BldwnA H683 <----- cuttered -

John Cotton's Middle Way

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 John Cotton's Middle Way Gary Albert Rowland Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Rowland, Gary Albert, "John Cotton's Middle Way" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 251. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/251 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN COTTON'S MIDDLE WAY A THESIS presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History The University of Mississippi by GARY A. ROWLAND August 2011 Copyright Gary A. Rowland 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Historians are divided concerning the ecclesiological thought of seventeenth-century minister John Cotton. Some argue that he supported a church structure based on suppression of lay rights in favor of the clergy, strengthening of synods above the authority of congregations, and increasingly narrow church membership requirements. By contrast, others arrive at virtually opposite conclusions. This thesis evaluates Cotton's correspondence and pamphlets through the lense of moderation to trace the evolution of Cotton's thought on these ecclesiological issues during his ministry in England and Massachusetts. Moderation is discussed in terms of compromise and the abatement of severity in the context of ecclesiastical toleration, the balance between lay and clerical power, and the extent of congregational and synodal authority. -

Curriculum Vitae—Greg Salazar

GREG A. SALAZAR ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF HISTORICAL THEOLOGY PURITAN REFORMED THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY PHD CANDIDATE, THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE 2965 Leonard Street Phone: (616) 432-3419 Grand Rapids, MI 49525 Email: [email protected] PROFESSIONAL OBJECTIVE To train and form the next generation of Reformed Christian leaders through a career of teaching and publishing in the areas of church history, historical theology, and systematic theology. I also plan to serve the Presbyterian church as a teaching elder through a ministry of shepherding, teaching, and preaching. EDUCATION The University of Cambridge (Selwyn College) 2013-2017 (projected) PhD in History Dissertation: “Daniel Featley and Calvinist Conformity in Early Stuart England” Supervisor: Professor Alex Walsham Reformed Theological Seminary, Orlando 2009-2012 Master of Divinity The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2003-2007 Bachelor of Arts (Religious Studies) DOCTORAL RESEARCH My doctoral research is on the historical, theological, and intellectual contexts of the Reformation in England—specifically analyzing the doctrinal, ecclesiological, and pietistic links between puritanism and the post-Reformation English Church in the lead-up to the Westminster Assembly, through the lens of the English clergyman and Westminster divine Daniel Featley (1582-1645). AREAS OF RESEARCH SPECIALIZATION Broadly speaking, my competency and interests are in church history, historical theology, systematic theology, spiritual formation, and Islam. Specific Research Interests include: Post-Reformation -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Presbyterianism in Devon and Cornwall in the seventeenth century Gillespie, J. T. How to cite: Gillespie, J. T. (1943) Presbyterianism in Devon and Cornwall in the seventeenth century, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10460/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk PRBSBYTERIANISM IN DEVON AND GOmALL IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY. Thesis presented for the Degree of M.A. by the Rev. J.T. Gillespie,B.A. 31st. May,1943. Highfield, Venn Crescent, Plymouth. PRESBYTERIMISM IN DEVON AND GORW^ALL IN THS 17th. GSHTURY. The term '•Preshyterian" as it- was applied in this period of English history is a most confusing one. Through the relations of the Presbyterian party with the Independents^ tne Scottisn Church, and the political movements of the times, the name was very loosely applied, "but in general it is taken to mean all those who left the Church of England from 1660-1662 rather than accept the episcopal 'system and all that w_ent with it, unless they definitely called -^ ' themselves Bapti^for rn*5pendent. -

William Perkins (1558– 7:30 – 9:00 Pm 1602) Earned a Bachelor’S Plenary Session # 1 Degree in 1581 and a Mas- Dr

MaY 19 (FrIDaY eVeNING) William perkinS (1558– 7:30 – 9:00 pm 1602) earned a bachelor’s plenary Session # 1 degree in 1581 and a mas- Dr. Sinclair Ferguson, ter’s degree in 1584 from WILLIAM William Perkins—A Plain Preacher Christ’s College in Cam- bridge. During those stu- dent years he joined up PERKINS MaY 20 (SaTUrDaY MOrNING) with Laurence Chaderton, CONFereNCe 9:00 - 10:15 am who became his personal plenary Session # 2 tutor and lifelong friend. IN THE ROUND CHURCH Dr. Joel Beeke Perkins and Chaderton met William Perkins’s Largest Case of Conscience with Richard Greenham, Richard Rogers, and others in a spiritual brotherhood 10:30 – 11:45 am at Cambridge that espoused Puritan convictions. plenary Session # 3 Dr. Geoff Thomas From 1584 until his death, Perkins served as lectur- The Pursuit of Godliness in the er, or preacher, at Great St. Andrew’s Church, Cam- Ministry of William Perkins bridge, a most influential pulpit across the street from Christ’s College. He also served as a teaching fellow 12:00 – 6:45 pm at Christ’s College, catechized students at Corpus Free Time Christi College on Thursday afternoons, and worked as a spiritual counselor on Sunday afternoons. In MaY 20 (SaTUrDaY eVeNING) these roles Perkins influenced a generation of young 7:00 – 8:15 pm students, including Richard Sibbes, John Cotton, John plenary Session # 4 Preston, and William Ames. Thomas Goodwin wrote Dr. Stephen Yuille that when he entered Cambridge, six of his instruc- Contending for the Faith: Faith and Love in Perkins’s tors who had sat under Perkins were still passing on Defense of the Protestant Religion his teaching. -

'Very Sore Nights and Days': the Child's Experience of Illness in Early Modern England, C.1580–1720

Medical History, 2011, 55: 153–182 ‘Very Sore Nights and Days’: The Child’s Experience of Illness in Early Modern England, c.1580–1720 HANNAH NEWTON* Abstract: Sick children were ubiquitous in early modern England, and yet they have received very little attention from historians. Taking the elusive perspective of the child, this article explores the physical, emotional, and spiritual experience of illness in England between approximately 1580 and 1720. What was it like being ill and suffering pain? How did the young respond emotionally to the anticipation of death? It is argued that children’s experiences were characterised by profound ambivalence: illness could be terrifying and distressing, but also a source of emotional and spiritual fulfilment and joy. This inter- pretation challenges the common assumption amongst medical histor- ians that the experiences of early modern patients were utterly miserable. It also sheds light on children’s emotional feelings for their parents, a subject often overlooked in the historiography of childhood. The primary sources used in this article include diaries, autobiographies, letters, the biographies of pious children, printed possession cases, doc- tors’ casebooks, and theological treatises concerning the afterlife. Keywords: Child; Patient; Parents; Sickness; Pain; Death; Emotion; Providence; Puritanism; Heaven; Hell; Doctor; Paediatrics; Love; Siblings; Gender; Diaries; Letters; Casebooks; Possession Introduction ‘The Sick Child’, painted by Gabriel Metsu in 1660, inspired the subject of this article.1 The ailing child gazes listlessly out of the painting, her fragile, pale form contrasting against the solid, bright presence of her nurse or mother.2 Although the painting is Dutch, it sparks a host of questions relevant to children’s experiences of illness in early modern Europe as a whole. -

Preparation for Grace in Puritanism: an Evaluation from the Perspective of Reformed Anthropology

Diligentia: Journal of Theology and Christian Education E-ISSN: 2686-3707 ojs.uph.edu/index.php/DIL Preparation for Grace in Puritanism: An Evaluation from the Perspective of Reformed Anthropology Hendra Thamrindinata Faculty of Liberal Arts, Universitas Pelita Harapan [email protected] Abstract The Puritans’ doctrine on the preparation for grace, whose substance was an effort to find and to ascertain the true marks of conversion in a Christian through several preparatory steps which began with conviction or awakening, proceeded to humiliation caused by a sense of terror of God’s condemnation, and finally arrived into regeneration, introduced in the writings of such first Puritans as William Perkins (1558-1602) and William Ames (1576-1633), has much been debated by scholars. It was accused as teaching salvation by works, a denial of faith and assurance, and a divergence from Reformed teaching of human's total depravity. This paper, on the other hand, suggesting anthropology as theological presupposition behind this Puritan’s preparatory doctrine, through a historical-theological analysis and elaboration of the post-fall anthropology of Calvin as the most influential theologian in England during Elizabethan era will argue that this doctrine was fit well within Reformed system of believe. Keywords: Puritan, Reformed Theology, William Perkins, William Ames, England, Grace. Introduction In his book on Jonathan Edwards’s biography, Marsden tells a story about Edwards’s struggle with a question related to his spirituality, whether -

Calamy 1713 Volume 2 Text.Qxp:Calamy 1713 Volume 2 14 12 2008 23:36 Page 1

Calamy_1713_Volume_2_Text.qxp:Calamy 1713 Volume 2 14 12 2008 23:36 Page 1 EDMUND CALAMY AN ACCOUNT OF THE Ministers, Lecturers, Masters and Fellows of Colleges and Schoolmasters, who were Ejected or Silenced after the Restoration in 1660. By, or before, the ACT for UNIFORMITY. 1713 Calamy_1713_Volume_2_Text.qxp:Calamy 1713 Volume 2 14 12 2008 23:36 Page 1 AN ACCOUNT OF THE Ministers, Lecturers, Masters and Fellows of COLLEGES and Schoolmasters, WHO WERE Ejected or Silenced AFTER THE RESTORATION in 1660. By, or before, the ACT for UNIFORMITY. Quinta Press Calamy_1713_Volume_2_Text.qxp:Calamy 1713 Volume 2 14 12 2008 23:36 Page 2 Quinta Press, Meadow View, Weston Rhyn, Oswestry, Shropshire, England, SY10 7RN The format of this book is copyright © 2008 Quinta Press This is a proof-reading draft of this volume. When all five volumes have an accurate text we will import the biographical material of the jected ministers into a database for collation and sorting and will then output the information in a variety of ways, some for electronic publication and some for print publication. Calamy_1713_Volume_2_Text.qxp:Calamy 1713 Volume 2 14 12 2008 23:36 Page 3 1713 edition volume 2 3 AN ACCOUNT OF THE Ministers, Lecturers, Masters and Fellows of COLLEGES and Schoolmasters, WHO WERE Ejected or Silenced AFTER THE RESTORATION in 1660. By, or before, the ACT for UNIFORMITY. Design’d for the preserving to Posterity, the Memory of their Names, Characters, Writings and Sufferings. The Second Edition: In Two Volumes. Vol. II. By EDMUND CALAMY, D.D. LONDON: Printed for Lawrence, in the Poultrey; J.