The Preacher-Physicians of Colonial New England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capper 1998 Phd Karl Barth's Theology Of

Karl Barth’s Theology of Joy John Mark Capper Selwyn College Submitted for the award of Doctor of Philosophy University of Cambridge April 1998 Karl Barth’s Theology of Joy John Mark Capper, Selwyn College Cambridge, April 1998 Joy is a recurrent theme in the Church Dogmatics of Karl Barth but it is one which is under-explored. In order to ascertain reasons for this lack, the work of six scholars is explored with regard to the theme of joy, employing the useful though limited “motifs” suggested by Hunsinger. That the revelation of God has a trinitarian framework, as demonstrated by Barth in CD I, and that God as Trinity is joyful, helps to explain Barth’s understanding of theology as a “joyful science”. By close attention to Barth’s treatment of the perfections of God (CD II.1), the link which Barth makes with glory and eternity is explored, noting the far-reaching sweep which joy is allowed by contrast with the related theme of beauty. Divine joy is discerned as the response to glory in the inner life of the Trinity, and as such is the quality of God being truly Godself. Joy is seen to be “more than a perfection” and is basic to God’s self-revelation and human response. A dialogue with Jonathan Edwards challenges Barth’s restricted use of beauty in his theology, and highlights the innovation Barth makes by including election in his doctrine of God. In the context of Barth’s anthropology, paying close attention to his treatment of “being in encounter” (CD III.2), there is an examination of the significance of gladness as the response to divine glory in the life of humanity, and as the crowning of full and free humanness. -

P E E L C H R Is T Ian It Y , Is L a M , an D O R Isa R E Lig Io N

PEEL | CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, AND ORISA RELIGION Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Christianity, Islam, and Orisa Religion THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF CHRISTIANITY Edited by Joel Robbins 1. Christian Moderns: Freedom and Fetish in the Mission Encounter, by Webb Keane 2. A Problem of Presence: Beyond Scripture in an African Church, by Matthew Engelke 3. Reason to Believe: Cultural Agency in Latin American Evangelicalism, by David Smilde 4. Chanting Down the New Jerusalem: Calypso, Christianity, and Capitalism in the Caribbean, by Francio Guadeloupe 5. In God’s Image: The Metaculture of Fijian Christianity, by Matt Tomlinson 6. Converting Words: Maya in the Age of the Cross, by William F. Hanks 7. City of God: Christian Citizenship in Postwar Guatemala, by Kevin O’Neill 8. Death in a Church of Life: Moral Passion during Botswana’s Time of AIDS, by Frederick Klaits 9. Eastern Christians in Anthropological Perspective, edited by Chris Hann and Hermann Goltz 10. Studying Global Pentecostalism: Theories and Methods, by Allan Anderson, Michael Bergunder, Andre Droogers, and Cornelis van der Laan 11. Holy Hustlers, Schism, and Prophecy: Apostolic Reformation in Botswana, by Richard Werbner 12. Moral Ambition: Mobilization and Social Outreach in Evangelical Megachurches, by Omri Elisha 13. Spirits of Protestantism: Medicine, Healing, and Liberal Christianity, by Pamela E. -

Seeking a Forgotten History

HARVARD AND SLAVERY Seeking a Forgotten History by Sven Beckert, Katherine Stevens and the students of the Harvard and Slavery Research Seminar HARVARD AND SLAVERY Seeking a Forgotten History by Sven Beckert, Katherine Stevens and the students of the Harvard and Slavery Research Seminar About the Authors Sven Beckert is Laird Bell Professor of history Katherine Stevens is a graduate student in at Harvard University and author of the forth- the History of American Civilization Program coming The Empire of Cotton: A Global History. at Harvard studying the history of the spread of slavery and changes to the environment in the antebellum U.S. South. © 2011 Sven Beckert and Katherine Stevens Cover Image: “Memorial Hall” PHOTOGRAPH BY KARTHIK DONDETI, GRADUATE SCHOOL OF DESIGN, HARVARD UNIVERSITY 2 Harvard & Slavery introducTION n the fall of 2007, four Harvard undergradu- surprising: Harvard presidents who brought slaves ate students came together in a seminar room to live with them on campus, significant endow- Ito solve a local but nonetheless significant ments drawn from the exploitation of slave labor, historical mystery: to research the historical con- Harvard’s administration and most of its faculty nections between Harvard University and slavery. favoring the suppression of public debates on Inspired by Ruth Simmon’s path-breaking work slavery. A quest that began with fears of finding at Brown University, the seminar’s goal was nothing ended with a new question —how was it to gain a better understanding of the history of that the university had failed for so long to engage the institution in which we were learning and with this elephantine aspect of its history? teaching, and to bring closer to home one of the The following pages will summarize some of greatest issues of American history: slavery. -

The Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society, Volume 11, 1916

The Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society, Volume 11, 1916 Table of Contents OFFICERS AND COMMITTEES .......................................................................................5 PROCEEDINGS OF THE THIRTY-SEVENTH TO THIRTY-NINTH MEETINGS .............................................................................................7 PAPERS EXTRACTS FROM LETTERS OF THE REVEREND JOSEPH WILLARD, PRESIDENT OF HARVARD COLLEGE, AND OF SOME OF HIS CHILDREN, 1794-1830 . ..........................................................11 By his Grand-daughter, SUSANNA WILLARD EXCERPTS FROM THE DIARY OF TIMOTHY FULLER, JR., AN UNDERGRADUATE IN HARVARD COLLEGE, 1798- 1801 ..............................................................................................................33 By his Grand-daughter, EDITH DAVENPORT FULLER BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH OF MRS. RICHARD HENRY DANA ....................................................................................................................53 By MRS. MARY ISABELLA GOZZALDI EARLY CAMBRIDGE DIARIES…....................................................................................57 By MRS. HARRIETTE M. FORBES ANNUAL REPORT OF THE TREASURER ........................................................................84 NECROLOGY ..............................................................................................................86 MEMBERSHIP .............................................................................................................89 OFFICERS OF THE SOCIETY -

Professional Office Suites 45 Lyman Street Westborough, Massachusetts

Welcome to Professional Office Suites 45 Lyman Street Westborough, Massachusetts 45 Lyman Street --- Westborough, Massachusetts “Our Business is to provide the perfect place for you to operate your business” Turn key units available - We believe that when you are ready to lease office space; it should be ready for you! That is the Turn Key Concept! We have a variety of floor plans that are available for you to pick the one that’s right for your company! The day your lease begins… the movers bring in your furniture, files and office supplies and you’re in business! There is no additional cost for our standard existing build out and no delay! Rent includes landscaping, snow removal, cleaning common areas, real estate taxes, parking lot maintenance, public lighting and water and sewer charges. There is no “balance billing” for real estate taxes or other common area costs. You pay one known sum each month, no surprises later. ♦ Card swipe system for off hours building access. Entry doors automatically lock after business hours. ♦ Convenient and ample parking at each end of the building. ♦ Excellent Location! Travel east or west easily at Lyman Street traffic lights. No “back tracking.” ♦ 24-hour emergency access number - which will page maintenance personnel. ♦ Cozy yet spacious atrium lobby with cathedral ceiling, skylights and an elevator awaiting to take you to your floor ♦ Impressive archway leading to double doors to welcome you and your business clients to your office. ♦ Fiber optic and cable ready ♦ Buildings kept immaculate at all times ♦ Walking distance to restaurants and stores ♦ Full handicap access to all areas ♦ Extra wide and spacious hallways with a brass plaque identifying each tenant next to the suite door. -

Table of Contents

The Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society, Volume 38, 1959-1960 Table Of Contents OFFICERS............................................................................................................5 PAPERS THE COST OF A HARVARD EDUCATION IN THE PURITAN PERIOD..........................7 BY MARGERY S. FOSTER THE HARVARD BRANCH RAILROAD, 1849-1855..................................................23 BY ROBERT W. LOVETT RECOLLECTIONS OF THE CAMBRIDGE SOCIAL DRAMATIC CLUB........................51 BY RICHARD W. HALL NATURAL HISTORY AT HARVARD COLLEGE, 1788-1842......................................69 BY JEANNETTE E. GRAUSTEIN THE REVEREND JOSE GLOVER AND THE BEGINNINGS OF THE CAMBRIDGE PRESS.............................................................................87 BY JOHN A. HARNER THE EVOLUTION OF CAMBRIDGE HEIGHTS......................................................111 BY LAURA DUDLEY SAUNDERSON THE AVON HOME............................................................................................121 BY EILEEN G. MEANY MEMORIAL BREMER WHIDDON POND...............................................................................131 BY LOIS LILLEY HOWE ANNUAL REPORTS.............................................................................................133 MEMBERS..........................................................................................................145 THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORICAL SOCIETY PROCEEDINGS FOR THE YEARS 1959-60 LIST OF OFFICERS FOR THESE TWO YEARS 1959 President Mrs. George w. -

REVEREND WILLIAM NOYES, Born, ENGLAND, 1568

DESCENDANTS OF REVEREND WILLIAM NOYES, BoRN, ENGLAND, 1568, IN DIRECT LINE TO LAVERNE W. NOYES, AND FRANCES ADELIA NOYES-GIFFEN. ALLIED FAMILIES OF STANTON. LORD. SANFORD. CODDINGTON. THOMPSON. FELLOWS. HOLDREDGE. BERRY. SAUNDERS. CLARKE. JESSUP. STUDWELL. RUNDLE. FERRIS. LOCKWOOD. PUBLISHED BY LA VERNE W. NO-YES, CHICAGO; ILLINOIS. 1900. PRESS OF 52 W. JACJCSON ST. LAV ERSE W. N oYi-:s. ~u9fi persona[ interest, and curiosity, as to liis antecedents, f lie pu6frslier of tliis 6ook lias 9atliered, and caused to 6e 9atliered, tlie statistics lierein contained. $ecause flieg Cfl)ere so dijficaft to coffed, as CftJe{{ as to figlifen tlie task of of liers of liis ~ind . red cwlio mag liave a simifar curious interest in ancesfrg, lie decided to print f.iem, and liopes tliat tlieg mag prove of maferiaf assistance to otliers. e&af/erne W. J2oges. CHICAGO, 1900. NOYES FAMILY. Reverend William Noyes was born in England during the year 1568. He matriculated at University College, Oxford, 15 November, 1588, at the age of twenty years, and was graduated B. A., 31 May, 1592. He was Rector of the Parish of Choulderton in Wiltshire, situated between Amesbury in Wiltshire and Andover in Hampshire, and eleven mile~ from Salisbury, which contains the great Salisbury Cathedral, built in the year 1220 A. D., whose lofty tower overlooks the dead Roman city of Sarum and '' Stonehenge," the ruins of the won derful pre-historic temple of the ancient Celtic Druids, in the midst of Salisbury Plain. The register of the Diocese shows that he officiated in the Parish from 1602 to 1620, at which time he resigned. -

Providence in the Life of John Hull: Puritanism and Commerce in Massachusetts Bay^ 16^0-1680

Providence in the Life of John Hull: Puritanism and Commerce in Massachusetts Bay^ 16^0-1680 MARK VALERI n March 1680 Boston merchant John Hull wrote a scathing letter to the Ipswich preacher William Hubbard. Hubbard I owed him £347, which was long overdue. Hull recounted how he had accepted a bill of exchange (a promissory note) ftom him as a matter of personal kindness. Sympathetic to his needs, Hull had offered to abate much of the interest due on the bill, yet Hubbard still had sent nothing. 'I have patiently and a long time waited,' Hull reminded him, 'in hopes that you would have sent me some part of the money which I, in such a ftiendly manner, parted with to supply your necessities.' Hull then turned to his accounts. He had lost some £100 in potential profits from the money that Hubbard owed. The debt rose with each passing week.' A prominent citizen, militia officer, deputy to the General Court, and affluent merchant, Hull often cajoled and lectured his debtors (who were many), moralized at and shamed them, but never had he done what he now threatened to do to Hubbard: take him to court. 'If you make no great matter of it,' he warned I. John Hull to William Hubbard, March 5, 1680, in 'The Diaries of John Hull,' with appendices and letters, annotated by Samuel Jennison, Transactions of the American Anti- quarian Society, II vols. (1857; repn. New York, 1971), 3: 137. MARK \i\LERi is E. T. Thompson Professor of Church History, Union Theological Seminary, Richmond, Virginia. -

2015 Annual Report on Giving 2 | Unitarian Universalist Association

Annual Report on Giving Unitarian Universalist Association 2015 Annual Report on Giving 2 | Unitarian Universalist Association Contents Letter from the President 3 The Board of Trustees 5 Your Gifts In Action for Our Congregations & Ministers 6 Highlights from General Assembly 8 Social Justice Highlights 10 Annual Program Fund & GIFT in the Southern Region 12 Meet the UU Fellowship of San Dieguito 14 Giving Summary 15 Congregational Honor Roll 16 25+ Year Honor Congregations 16 10+ Year Honor Congregations 19 Honor Congregations 25 Merit Congregations 30 Leadership Congregations 33 Unitarian Universalist Association Giving Societies 35 Presidential Partners 35 Leadership Partners 35 Visionary Partners 36 Covenant Stewards 36 Chalice Stewards 36 Fellowship Friends 39 Spirit Friends 42 Friends of the UUA ($100+) 49 Meet Gabe and Betsy Gelb 74 In Memoriam 2014-2015 75 In Memoriam: Donald Ross 76 Faithful Sustainers Circle 77 UU Veatch Program at Shelter Rock 78 The President’s Council 79 2015 Annual Report on Giving | 3 Letter from the President Dear Friend, I am delighted to present the Annual Report of the Unitarian Universalist Association for the 2015 Fiscal Year. This year has been filled with successes, challenges, and adventures as our Association continues to be a strong liberal religious voice. This past fiscal year has been full of opportunities to make a difference in our congregations, our communities, and in the larger world. In September of 2014, we launched Commit2Respond, a coalition of Unitarian Universalists and other people of faith and conscience working for climate justice. The following spring, we celebrated Climate Justice Month with 30 days of online messages to guide and grow engagement on this issue. -

A Quarterly Magazine Devoted to the Biography, Genealogy, History and Antiquities of Essex County, Massachusetts

A QUARTERLY MAGAZINE DEVOTED TO THE BIOGRAPHY, GENEALOGY, HISTORY AND ANTIQUITIES OF ESSEX COUNTY, MASSACHUSETTS SIDNEY PERLEY, EDITOR ILLUSTRATED SALEM, MASS. Qbt Qtsse~Bntiqaarfan 1905 CONTENTS. ANswEns, 88, r43; 216, 47; 393, 48; 306, 95; EWETI, MRS. ANN,Will of, 159. 307, 95; 3149 95; 425, 191 ; 4387 191; 44% f EWBTT, JOSEPH,Will of, 113. 143. LAMBERT,FRANCIS, Will of, 36. BANK,T?IS LAND, 135. LAMBERT,JANE, Will of, 67. BAY VIEW CEM~ERY,*GLOUCESTEX, INSCPIP- LAND BANK, The, 135. n0NS IN. 68. LANESVILLB,GWUCBSTBII, INSCRIPTIONS IN BEUY NOTBS,25, 86. OLD CEMETERYAT, 106. B~sco.ELIZABETH, 108. ~THA'SVINEYARD, ESSEX COUNTY MEN AT, BISHOPNOTES, I 13. BEFORE 1700, 134. BLANCHAWGENEAL~GIES, 26, 71. NEW PUBLICATIONS,48,95, 143, 192. BUSY GBNBALOCY,32. NORFOLK COUNTY RECORDS,OW, 137. BLASDIULGENRALOGY, 49. OLDNORFOLK COUNTY RECORDS, 137. B~vmGENSUOGY, I I o. PARRUT,FRANCIS, Will of, 66. BLYTHGENEALOGY, I 12. PEABODY,REV. OLIVER.23. BOARDMAN 145. PBASLEY, JOSEPH,Wd of, 123. ~DwSLLGENMLOOY, 171. PERKINS,JOHN, Will of, 45. BOND GENBALOGY,177. PIKE, JOHN,SR, Wi of, 64. BRIDGE, THS OLD,161. PISCATAQUAPIONEERS, 191. BROWNB,RICHARD, Will of, 160. &SEX COUNTY MEN AT ARTHA HA'S VINEYARD 143; 451, 45% 191. swoas 1700, 134. ROGEILS.REV. EZEKIEL,Will of, 104. CLOU-R INSCRIPTIONS: ROGERSREV. NATHANIEL. Wi of. 6~. Ancient Buying Ground, I. SALEMCOURT RECORDSAND FI&, 61,154. Bay View Cemetery, 68. SALEMIN 1700, NO. 18, 37. Old Cemetery at knesville, 106. SALEMIN 1700, NO. 19, 72. Ancient Cemetey, West Gloucester, 152. SALEMIN 1/00, NO. 20, 114. HYMNS,THE OLD,142. SALEMIN 1700, NO. -

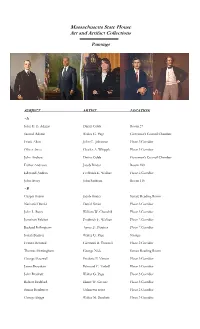

Open PDF File, 134.33 KB, for Paintings

Massachusetts State House Art and Artifact Collections Paintings SUBJECT ARTIST LOCATION ~A John G. B. Adams Darius Cobb Room 27 Samuel Adams Walter G. Page Governor’s Council Chamber Frank Allen John C. Johansen Floor 3 Corridor Oliver Ames Charles A. Whipple Floor 3 Corridor John Andrew Darius Cobb Governor’s Council Chamber Esther Andrews Jacob Binder Room 189 Edmund Andros Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor John Avery John Sanborn Room 116 ~B Gaspar Bacon Jacob Binder Senate Reading Room Nathaniel Banks Daniel Strain Floor 3 Corridor John L. Bates William W. Churchill Floor 3 Corridor Jonathan Belcher Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor Richard Bellingham Agnes E. Fletcher Floor 2 Corridor Josiah Benton Walter G. Page Storage Francis Bernard Giovanni B. Troccoli Floor 2 Corridor Thomas Birmingham George Nick Senate Reading Room George Boutwell Frederic P. Vinton Floor 3 Corridor James Bowdoin Edmund C. Tarbell Floor 3 Corridor John Brackett Walter G. Page Floor 3 Corridor Robert Bradford Elmer W. Greene Floor 3 Corridor Simon Bradstreet Unknown artist Floor 2 Corridor George Briggs Walter M. Brackett Floor 3 Corridor Massachusetts State House Art Collection: Inventory of Paintings by Subject John Brooks Jacob Wagner Floor 3 Corridor William M. Bulger Warren and Lucia Prosperi Senate Reading Room Alexander Bullock Horace R. Burdick Floor 3 Corridor Anson Burlingame Unknown artist Room 272 William Burnet John Watson Floor 2 Corridor Benjamin F. Butler Walter Gilman Page Floor 3 Corridor ~C Argeo Paul Cellucci Ronald Sherr Lt. Governor’s Office Henry Childs Moses Wight Room 373 William Claflin James Harvey Young Floor 3 Corridor John Clifford Benoni Irwin Floor 3 Corridor David Cobb Edgar Parker Room 222 Charles C. -

Early Puritanism in the Southern and Island Colonies

Early Puritanism in the Southern and Island Colonies BY BABETTE M. LEVY Preface NE of the pleasant by-products of doing research O work is the realization of how generously help has been given when it was needed. The author owes much to many people who proved their interest in this attempt to see America's past a little more clearly. The Institute of Early American History and Culture gave two grants that enabled me to devote a sabbatical leave and a summer to direct searching of colony and church records. Librarians and archivists have been cooperative beyond the call of regular duty. Not a few scholars have read the study in whole or part to give me the benefit of their knowledge and judgment. I must mention among them Professor Josephine W, Bennett of the Hunter College English Department; Miss Madge McLain, formerly of the Hunter College Classics Department; the late Dr. William W. Rockwell, Librarian Emeritus of Union Theological Seminary, whose vast scholarship and his willingness to share it will remain with all who knew him as long as they have memories; Professor Matthew Spinka of the Hartford Theological Sem- inary; and my mother, who did not allow illness to keep her from listening attentively and critically as I read to her chapter after chapter. All students who are interested 7O AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY in problems concerning the early churches along the Atlantic seaboard and the occupants of their pulpits are indebted to the labors of Dr. Frederick Lewis Weis and his invaluable compendiums on the clergymen and parishes of the various colonies.