Ksu-45-05-001-03127-2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

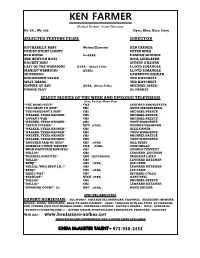

K E N F a R M

KEN FAR MER (Partial Resume- Actor/Director) Ht: 6ft., Wt: 200 Eyes: Blue, Hair: Grey SELECTED FEATURE FILMS DIRECTOR ROCKABILLY BABY Writer/Director KEN FARMER FRIDAY NIGHT LIGHTS PETER BERG RED RIDGE Co-STAR DAMIAN SKINNER THE NEWTON BOYS RICK LINKLATER ROCKET MAN STUART GILLARD LAST OF THE WARRIORS (STAR, - Above Title) LLOYD SIMANDLE MANIAC WARRIORS (STAR) LLOYD SIMANDLE SILVERADO LAWRENCE KASDAN UNCOMMON VALOR TED KOTCHEFF SPLIT IMAGE TED KOTCHEFF EMPIRE OF ASH (STAR - Above Title) MICHAEL MAZO POWER PLAY AL FRAKES SELECT MOVIES OF THE WEEK AND EPISODIC TELEVISION (Star, Co-Star, Guest Star) “THE GOOD GUYS” FOX SANFORD BOOKSTAVER "TOO LEGIT TO QUIT" VH1 ARTIE MANDELBERG "THE PRESIDENT'S MAN" CBS MICHAEL PREECE "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS MICHAEL PREECE "LOGAN'S WAR" CBS MICHAEL PREECE "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS TONY MORDENTE "AUSTIN STORIES" MTV (STAR) GEORGE VERSHOOR "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS ALEX SINGER "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS TONY MORDENTE "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS MICHAEL PREECE "WALKER, TEXAS RANGER" CBS TONY MORDENTE "ANOTHER PAIR OF ACES" CBS (STAR) BILL BIXBY "AMERICA'S MOST WANTED" FOX (STAR) TOM SHELLY "HIGH MOUNTAIN RANGERS" CBS GEORGE FENNEDY "DALLAS" CBS LEONARD KATZMAN "GENERAL HOSPITAL" ABC (RECURRING) MARLENA LAIRD "DALLAS" CBS LEONARD KATZMAN "BENJI" CBS (STAR) JOE CAMP "DALLAS, WHO SHOT J.R.?" CBS LEONARD KATZMAN "BENJI" CBS (STAR) JOE CAMP "JAKE'S WAY" CBS RICHARD COLLA "BACKLOT" NICK (STAR) GARY PAUL "DALLAS" CBS MICHAEL PREECE "DALLAS" CBS LEONARD KATZMAN "SUPERIOR COURT" (2) NBC (STAR) HANK GRIMER SPECIAL ABILITIES EXPERT HORSEMAN: ALL SPORTS: COLLEGE ALL-AMERICAN, FOOTBALL: EXCELLENT SWIMMER: DIVING: SCUBA: WRESTLING: HAND-TO-HAND COMBAT: USMC: FAMILIAR WITH ALL TYPES OF FIREARMS: CAN FURNISH OWN FILM TRAINED HORSE: BACHELOR'S DEGREE - SPEECH & DRAMA : GOLF: AUTHOR OF "ACTING IS STORYTELLING ©" : ACTING COACH: STORYTELLING CONSULTANT: PRODUCER: DIRECTOR Web Site - www.kenfarmer-author.net THEATRICAL AND COMMERCIAL DVD & AUDIO TAPES AVAILABLE LINDA McALISTER TALENT - 972-938-2433. -

'Perfect Fit': Industrial Strategies, Textual Negotiations and Celebrity

‘Perfect Fit’: Industrial Strategies, Textual Negotiations and Celebrity Culture in Fashion Television Helen Warner Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Film and Television Studies Submitted July 2010 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author's prior, written consent. Helen Warner P a g e | 2 ABSTRACT According to the head of the American Costume Designers‟ Guild, Deborah Nadoolman Landis, fashion is emphatically „not costume‟. However, if this is the case, how do we approach costume in a television show like Sex and the City (1998-2004), which we know (via press articles and various other extra-textual materials) to be comprised of designer clothes? Once onscreen, are the clothes in Sex and the City to be interpreted as „costume‟, rather than „fashion‟? To be sure, it is important to tease out precise definitions of key terms, but to position fashion as the antithesis of costume is reductive. Landis‟ claim is based on the assumption that the purpose of costume is to tell a story. She thereby neglects to acknowledge that the audience may read certain costumes as fashion - which exists in a framework of discourses that can be located beyond the text. This is particularly relevant with regard to contemporary US television which, according to press reports, has witnessed an emergence of „fashion programming‟ - fictional programming with a narrative focus on fashion. -

The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams by Cynthia A. Burkhead A

Dancing Dwarfs and Talking Fish: The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams By Cynthia A. Burkhead A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Ph.D. Department of English Middle Tennessee State University December, 2010 UMI Number: 3459290 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3459290 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DANCING DWARFS AND TALKING FISH: THE NARRATIVE FUNCTIONS OF TELEVISION DREAMS CYNTHIA BURKHEAD Approved: jr^QL^^lAo Qjrg/XA ^ Dr. David Lavery, Committee Chair c^&^^Ce~y Dr. Linda Badley, Reader A>& l-Lr 7i Dr./ Jill Hague, Rea J <7VM Dr. Tom Strawman, Chair, English Department Dr. Michael D. Allen, Dean, College of Graduate Studies DEDICATION First and foremost, I dedicate this work to my husband, John Burkhead, who lovingly carved for me the space and time that made this dissertation possible and then protected that space and time as fiercely as if it were his own. I dedicate this project also to my children, Joshua Scanlan, Daniel Scanlan, Stephen Burkhead, and Juliette Van Hoff, my son-in-law and daughter-in-law, and my grandchildren, Johnathan Burkhead and Olivia Van Hoff, who have all been so impressively patient during this process. -

Science Fiction Films of the 1950S Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 "Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noonan, Bonnie, ""Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3653. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3653 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “SCIENCE IN SKIRTS”: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN SCIENCE IN THE “B” SCIENCE FICTION FILMS OF THE 1950S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Bonnie Noonan B.G.S., University of New Orleans, 1984 M.A., University of New Orleans, 1991 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Bonnie Noonan All rights reserved ii This dissertation is “one small step” for my cousin Timm Madden iii Acknowledgements Thank you to my dissertation director Elsie Michie, who was as demanding as she was supportive. Thank you to my brilliant committee: Carl Freedman, John May, Gerilyn Tandberg, and Sharon Weltman. -

The Use and Abuse of Global Telepoiesis: of Human and Non-Human Bondages Entangled in Media Mobilities

Keio Communication Review No.39, 2017 The Use and Abuse of Global Telepoiesis: Of Human and Non-Human Bondages Entangled in Media Mobilities OGAWA NISHIAKI Yoko* Introduction Collective memory is not an archive that is concealed or defiant to any access. Rather, collective memory is open to re-interpretation. Also, collective memory is displayed in various forms: names, folk tales, old films, TV programs and Japanese cinema on the big screen, which Japanese migrant women watch again but this time with local audiences in foreign cities. Media audience studies and other studies on diasporic media consumption (Morley, 1974, 1990; Collins et al., 1986; Liebes & Katz, 1990; Ang, 1991; Livingstone, 1998; Moores, 1993; Ogawa, 1992) have been endeavoring to examine readings of specific media texts in relation to audience so far. On the contrary, more detailed analysis of collective memory will be required to understand the global media mobilities we encounter in the past decades (Zelizer, 1993; Gillespie, 1995; Fortier, 2000). This paper will focus on recursivity by shifting the emphasis from meaning of the text itself to how collective memories in talks act as sites, namely time-spaces (Scannell, 1988, 1991; Gilroy et al., 2000). It is this type of media mobilities with which the Japanese women who live abroad try to locate themselves somewhere local amid the global upheavals they encounter (Ogawa, 1994, 1996; Urry, 2007; 1 Elliot & Urry, 2010) . With emphasis on Japanese women, who are unfamiliar with war memories but are destined to recursively cope with them, diasporic experiences in relation with media, history and self-identity will be highlighted (Dower, 1986; Goodman, 1990; Clair et al., 2016). -

Cross Cultural Readings of American TV

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication 1-1990 Interacting With "Dallas": Cross Cultural Readings of American TV Elihu Katz University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Tamar Liebes Hebrew University of Jerusalem Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons Recommended Citation Katz, E., & Liebes, T. (1990). Interacting With "Dallas": Cross Cultural Readings of American TV. Canadian Journal of Communication, 15 (1), 45-66. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/159 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/159 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interacting With "Dallas": Cross Cultural Readings of American TV Abstract Decoding by overseas audiences of the American hit program, "Dallas," shows that viewers use the program as a "forum" to reflect on their identities. They become involved morally (comparing "them" and "us"), playfully (trying on unfamiliar roles), ideologically (searching for manipulative messages), and aesthetically (discerning the formulae from which the program is constructed). Keywords TV Disciplines Broadcast and Video Studies | Communication This journal article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/159 INTERACTING WITH "DALLAS": CROSS CULTURAL READINGS OF AMERICAN TV * Elihu Katz Tamar Liebes Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Annenberg School of Communications, University of Southern California *An early version of this paper was prepared for the Manchester Symposium on Broadcasting, March 5-6, 1985. We wish to thank Peter Clarke, Dean of the Annenberg School of Communications at the University of Southern California, for support of the research project on which the paper is based. -

Dallas (1978 TV Series)

Dallas (1978 TV series) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article is about the original 1978–1991 television series. For the sequel, see Dallas (2012 TV series). Dallas is a long-running American prime time television soap opera that aired from April 2, 1978, to May 3, 1991, on CBS. The series revolves around a wealthy and feuding Texan family, the Ewings, who own the independent oil company Ewing Oil and the cattle-ranching land of Southfork. The series originally focused on the marriage of Bobby Ewing and Pamela Barnes, whose families were sworn enemies with each other. As the series progressed, oil tycoon J.R. Ewing grew to be the show's main character, whose schemes and dirty business became the show's trademark.[1] When the show ended in May 1991, J.R. was the only character to have appeared in every episode. The show was famous for its cliffhangers, including the Who shot J.R.? mystery. The 1980 episode Who Done It remains the second highest rated prime-time telecast ever.[2] The show also featured a "Dream Season", in which the entirety of the ninth season was revealed to have been a dream of Pam Ewing's. After 14 seasons, the series finale "Conundrum" aired in 1991. The show had a relatively ensemble cast. Larry Hagman stars as greedy, scheming oil tycoon J.R. Ewing, stage/screen actressBarbara Bel Geddes as family matriarch Miss Ellie and movie Western actor Jim Davis as Ewing patriarch Jock, his last role before his death in 1981. The series won four Emmy Awards, including a 1980 Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series win for Bel Geddes. -

DEAN DENTON SAG/AFTRA Height: 6’0’’ Hair: Brown Eyes: Brown Weight: 195

(404) 874-6448 DEAN DENTON SAG/AFTRA www.deandenton.com Height: 6’0’’ Hair: Brown Eyes: Brown Weight: 195 FILM Devotion Supporting (Capt. Sisson) Director: J.D. Dillard/Black Label Media American Underdog Supporting (David Gillis) Director: Andrew Erwin/Lionsgate The Highwaymen Supporting (Bob Alcorn) Director: John Lee Hancock/Netflix Prods. Brian Banks Supporting (Coach Jaso) Director: Tom Shadyac/ShivHans Prods. God’s Not Dead: A Light in Darkness Supporting (Policeman) Director: Jon Gunn/GND 3 Prods. The Riot Act Supporting (Marshal) Director: Devon Parks/Riot Act Prods. The Whisperers Supporting (Dad) Director: Jason Miller/Rugged Prods. Faith Lead (Mike) Director: Dean Denton/Domino Prods. Thankful Hearts Lead (Derrick James) Director: Dean Denton/Domino Prods. Come Morning Supporting (Jim) Director: Derrick Sims/Fabeled Pictures Change Lead (John Kash) Director: Misty Steele/Open Eyes Prods. Bloodstone Diaries Supporting (Lungo) Director: Gerry Bruno/Let’s Think Prods. Ballerina Lead (Frank Gross) Director: Bryan Stafford/Ballerina Prods. Blind Turn Supporting (Father) Director: Robert Orr/Point O Seven Prods. Seven Souls Lead (Michael) Director: Gerry Bruno/Let’s Think Prods. Step Away From The Stone Lead (Dr. Harris) Director: Bill Barton/Rock Prods. Summertime Christmas Lead (Nick) Director: Andrew Ehrenkrook/Ehrenkrook Born on the Fourth of July Featured (Recruiter) Director: Oliver Stone/Ixtlan Prods. Riverbend Featured Director: Sam Firstenberg/Vandale Prods. Love Hurts Featured Director: Bud Yorkin/Vestron Pictures Paramedics Featured Director: Stuart Margolin/Crow Prods. Robo Cop Featured Director: Paul Verhoeven/Orion Pictures TELEVISION Women of the Movement Co-Star (Foreman) Director: Tina Mabry/Mazo Partners Finding Love in Mountain View Co-Star (Ted Banks) Director: Sandra L. -

The Coalition Does Not Believe That the FISR Must Be Preserved in Perpetuity. Future Changes in the Television Marketplace May W

The Coalition does not believe that the FISR must be preserved in perpetuity. Future changes in the television marketplace may well warrant relaxation of the Rule, and, ultimately, its repeal. That day, however, has not arrived. While the Coalition therefore supports Commission review of the Rule, undertaking a review of the FISR every two years has simply resulted in higher costs for the industry, both in terms of business uncertainty and transaction costs, as parties attempt to adapt to a rapidly changing regulatory landscape. Moreover, marketplace changes of the magnitude that would render the FISR unnecessary are unlikely to occur in a two-year period. Consequently, the Coalition urges the Commission to commit to review the Rule again in 1999. There is nothing to be lost, but much to be gained, from permitting the Commission this additional time to review the consequences of its deregulatory actions. On the one hand, a number of the trends discussed above -- e.g., the increase in in-house production, the reduction in production by small producers -- are continuing ones. It is impossible to determine, at this early stage, when the marketplace will reach some new equilibrium, or what that equilibrium will look like. In addition, once the marketplace has fully adjusted to the new regulatory regime, it will take some time to measure and evaluate the public interest consequences of the changes that have taken place. On the other hand, under a strengthened FISR, the networks will continue to be able to acquire financial interests in programs, subject to the separate negotiation safeguard. This will permit the marketplace to realize any efficiencies associated with network participation in program financing. -

Lrsing Home Or Campus -Veterans Nu

-Veterans NuLrsing Home Human Errors Foil Grades :.Planned' fi By George Bidermann or An "oversight" was responsible Campus for a computer error which caused all "D" grades given to under- By Mitchell Horowitz plete, according to Robert Kistler. the State Health graduates last semester to be recorded as unre- Plans to build a 350-bed veterans nursing home on Department's director of Institutional Management. ported grades, according to William Strockbine, the Stony Brook campus were announced in Governor Planning and construction costs are expected to be $25 the director of the Registrar. As a result, many - Mario Cuomo's January 6 State of the State address. In million, with 65 percent of that being supplied by the students were placed on academic notice, and some Albany yesterday the SUNY Board of Trustees ap- federal government. The brunt of operating costs, $11 were even sent letters of dismissal from the proved Cuomo's decision. million a year, will be handled mostly by the state, university. The state-run facility will be the administrative re- Kistler said. - Strockbine said the Registrar's Office changed sponsibility of the Stony Brook main campus and "The project will certainly have an educational com- the classification codes for undergraduates last se- * Health Sciences Center (HSC). The home will main- ponent," said Vice President for Campus Operations mester, from a system which categorized the stu- tain its own staff, yet certain main campus/HSC ser- Bob Francis. "It can be devised so that it is constant dent by the expected year of graduation to a "U-1 vices will be used to run it on a day-to-day basis. -

Dallas“ Anhand Bestimmter Kriterien

BACHELORARBEIT Rebecca Renz Original und Remake bzw. Fortführung am Beispiel der Serie „Dallas“ anhand bestimmter Kriterien Showing the original series and remake respectively the continuation by using the example of the series ”Dallas“ with the aid of specific criteria 2013 0 BACHELORARBEIT Frau Rebecca Renz Original und Remake bzw. Fortführung am Beispiel der Serie „Dallas“ anhand be- stimmter Kriterien 2013 1 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Original und Remake bzw. Fortführung am Beispiel der Serie „Dallas“ anhand be- stimmter Kriterien Autor/in: Frau Rebecca Renz Studiengang: Film und Fernsehen Seminargruppe: FF10w1-B Erstprüfer: Otto Altendorfer, Prof.Dr.phil. Zweitprüfer: Ulrich Florl, M.A. Einreichung: Ort, Datum 2 Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS Showing the original series and remake respectively the continuation by using the ex- ample of the series “Dallas” with the aid of specific criteria author: Ms. Rebecca Renz course of studies: Film and TV seminar group: FF10w1-B first examiner: Otto Altendorfer, Prof.Dr.phil. second examiner: Ulrich Florl, M.A. submission: Ort, Datum 3 Bibliografische Angaben Renz, Rebecca: Original und Remake bzw. Fortführung am Beispiel der Serie “Dallas” anhand bestimmter Kriterien Showing the original series and remake respectively the continuation by using the example of the series “Dallas” with the aid of specific criteria 50 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2013 Abstract Diese Bachelorarbeit befasst sich mit der US-amerikanischen Fernsehserie „Dallas“. Der Schwerpunkt wird hierbei auf das „Dallas“ gesetzt, das am 2.April 1978 im US- Fernsehen seine Premiere feierte und drei Jahre später auch in die deutsche Fernseh- landschaft Einzug hielt und diese nachdrücklich beeinflusste. -

"St. Elsewhere" Star Is Gradspeaker

c Volume 9, Number 6 College At Lincoln Center, Fordham University April 15-28,1987 Out With Old Spring is Here! Core Curriculum In With New Goes Back To Dohrmann Leadership Basics Fruitful, Says USG By Mary P. Dtxon By O.T. Mfflsap The long-awaited core curriculum wul arrive at Lincoln Center this fall semester. The Mellon As candidates campaigned this month for Committee designed a new, more unified core United Student Government senate and executive program. The new courses will affect freshmen board positions for the 1987-88 term, the issue and new adult students entering the College at common to almost every candidate was in one Lincoln Center. form or another creating a new sense of commu- The program was finalized last spring and will nity at the College at Lincoln Center. Although it be instituted in September. It will consist of two remains to be seen whether the USG can shake the general courses, "History and Knowing" and doldrums from CLC's students, the outgoing "Language and Knowing." Students will also be members of the 1986-87 USG, and those running required to take a two credit composition course. for re-election, seem to have put the reputation of The new program is based to a considerable the club back on a solid footing this year. extent on Excel and Freshman Interdisciplinary During the 1985-86 school year, the USG was Program, both which will be affected by the new marred by a lack of student interest in running for core curriculum. Proficiency Requirements, Area senate positions, the one-month disciplinary pro- Requirements, and FIP will be phased out.