Australian Maritime Issues 2005 SPC-A Annual Issues 2005 SPC-A Annual Edited by Gregory P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This for Rememberance 4 Th Anks to a Number of Readers Some More Information Has Come to Light Regarding the Australians at Jutland

ISSUE 137 SEPTEMBER 2010 Th is for Rememberance Fuel for Th ought: Nuclear Propulsion and the RAN Re-Introducing Spirituality to Character Training in the Royal Australian Navy Navy Aircrew Remediation Training People, Performance & Professionalism: How Navy’s Signature Behaviours will manage a ‘New Generation’ of Sailors Management of Executive Offi cers on Armidale Class Patrol Boats Th e very name of the Canadian Navy is under question... A brief look at Submarines before Oberon Amphibious Warfare – Th e Rising Tide (And Beyond…) Studies in Trait Leadership in the Royal Australian Navy – Vice Admiral Sir William Creswell JOURNAL OF THE 137 SEPT 2010.indd 1 21/07/10 11:33 AM Trusted Partner Depth of expertise Proudly the leading mission systems integrator for the Royal Australia Navy, Raytheon Australia draws on a 1300 strong Australian workforce and the proven record of delivering systems integration for the Collins Class submarine, Hobart Class Air Warfare Destroyer and special mission aircraft. Raytheon Australia is focused on the needs of the Australian Defence Force and has the backing of Raytheon Company — one of the most innovative, high technology companies in the world — to provide NoDoubt® confi dence to achieve our customer’s mission success. www.raytheon.com.au © 2009 Raytheon Australia. All rights reserved. “Customer Success Is Our Mission” is a registered trademark of Raytheon Company. Image: Eye in the Sky 137Collins SEPT Oct09 2010.indd A4.indd 12 21/10/200921/07/10 10:14:55 11:33 AM AM Issue 137 3 Letter to the Editor Contents Trusted Partner “The Australians At Jutland” This for Rememberance 4 Th anks to a number of readers some more information has come to light regarding the Australians at Jutland. -

Guns Blazing! Newsletter of the Naval Wargames Society No

All Guns Blazing! Newsletter of the Naval Wargames Society No. 290 – DECEMBER 2018 Extract from President Roosevelt’s, “Fireside Chat to the Nation”, 29 December 1940: “….we cannot escape danger by crawling into bed and pulling the covers over our heads……if Britain should go down, all of us in the Americas would be living at the point of a gun……We must produce arms and ships with every energy and resource we can command……We must be the great arsenal of democracy”. oOoOoOoOoOoOoOo The Poppies of four years ago at the Tower of London have been replaced by a display of lights. Just one of many commemorations around the World to mark one hundred years since the end of The Great War. Another major piece of art, formed a focal point as the UK commemorated 100 years since the end of the First World War. The ‘Shrouds of the Somme’ brought home the sheer scale of human sacrifice in the battle that came to epitomize the bloodshed of the 1914-18 war – the Battle of the Somme. Artist Rob Heard hand stitched and bound calico shrouds for 72,396 figures representing British Commonwealth servicemen killed at the Somme who have no known grave, many of whose bodies were never recovered and whose names are engraved on the Thiepval Memorial. Each figure of a human form, was individually shaped, shrouded and made to a name. They were laid out shoulder to shoulder in hundreds of rows to mark the Centenary of Armistice Day at Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park from 8-18th November 2018 filling an area of over 4000 square metres. -

The British Commonwealth and Allied Naval Forces' Operation with the Anti

THE BRITISH COMMONWEALTH AND ALLIED NAVAL FORCES’ OPERATION WITH THE ANTI-COMMUNIST GUERRILLAS IN THE KOREAN WAR: WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE OPERATION ON THE WEST COAST By INSEUNG KIM A dissertation submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham May 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines the British Commonwealth and Allied Naval forces operation on the west coast during the final two and a half years of the Korean War, particularly focused on their co- operation with the anti-Communist guerrillas. The purpose of this study is to present a more realistic picture of the United Nations (UN) naval forces operation in the west, which has been largely neglected, by analysing their activities in relation to the large number of irregular forces. This thesis shows that, even though it was often difficult and frustrating, working with the irregular groups was both strategically and operationally essential to the conduct of the war, and this naval-guerrilla relationship was of major importance during the latter part of the naval campaign. -

Quality Versus Quantity: Lessons for Canadian Naval Renewal

QUALITY VERSUS QUANTITY: LESSONS FOR CANADIAN NAVAL RENEWAL Commander C. R. Wood JCSP 45 PCEMI 45 Service Paper Étude militaire Disclaimer Avertissement Opinions expressed remain those of the author and do Les opinons exprimées n’engagent que leurs auteurs et not represent Department of National Defence or ne reflètent aucunement des politiques du Ministère de Canadian Forces policy. This paper may not be used la Défense nationale ou des Forces canadiennes. Ce without written permission. papier ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation écrite © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, représentée par le Minister of National Defence, 2019. ministre de la Défense nationale, 2019. CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE/COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 45/PCEMI 45 15 OCT 2018 DS545 COMPONENT CAPABILITIES QUALITY VERSUS QUANTITY: LESSONS FOR CANADIAN NAVAL RENEWAL By Commander C. R. Wood Royal Navy “This paper was written by a candidate « La présente étude a été rédigée par un attending the Canadian Forces College in stagiaire du Collège des Forces canadiennes fulfillment of one of the requirements of the pour satisfaire à l’une des exigences du Course of Studies. The paper is a scholastic cours. L’étude est un document qui se document, and thus contains facts and rapporte au cours et contient donc des faits opinions which the author alone considered et des opinions que seul l’auteur considère appropriate and correct for the subject. It appropriés et convenables au sujet. Elle ne does not necessarily reflect the policy or the reflète pas nécessairement la politique ou opinion of any agency, including the l’opinion d’un organisme quelconque, y Government of Canada and the Canadian compris le gouvernement du Canada et le Department of National Defence. -

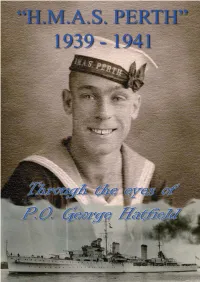

37845R CS3 Book Hatfield's Diaries.Indd

“H.M.A.S. PERTH” 1939 -1941 From the diaries of P.O. George Hatfield Published in Sydney Australia in 2009 Publishing layout and Cover Design by George Hatfield Jnr. Printed by Springwood Printing Co. Faulconbridge NSW 2776 1 2 Foreword Of all the ships that have flown the ensign of the Royal Australian Navy, there has never been one quite like the first HMAS Perth, a cruiser of the Second World War. In her short life of just less than three years as an Australian warship she sailed all the world’s great oceans, from the icy wastes of the North Atlantic to the steamy heat of the Indian Ocean and the far blue horizons of the Pacific. She survived a hurricane in the Caribbean and months of Italian and German bombing in the Mediterranean. One bomb hit her and nearly sank her. She fought the Italians at the Battle of Matapan in March, 1941, which was the last great fleet action of the British Royal Navy, and she was present in June that year off Syria when the three Australian services - Army, RAN and RAAF - fought together for the first time. Eventually, she was sunk in a heroic battle against an overwhelming Japanese force in the Java Sea off Indonesia in 1942. Fast and powerful and modern for her times, Perth was a light cruiser of some 7,000 tonnes, with a main armament of eight 6- inch guns, and a top speed of about 34 knots. She had a crew of about 650 men, give or take, most of them young men in their twenties. -

Japan Im Ersten Weltkrieg

ÖSTERREICHISCHEÖMZ MILITÄRISCHE ZEITSCHRIFT In dieser Onlineausgabe Harald Pöcher Japan im Ersten Weltkrieg Nikolaus Scholik Power-Projection vs Anti-Access/Area-Denial (A2/AD) Die operationellen Konzepte von U.S. Navy (USN) und Peoples Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) im Indo-Pazifischen Raum Andreas Armborst Dschihadismus im Irak Andreas Steiger Die Berufsoffiziersausbildung an der Theresianischen Militärakademie in Wr. Neustadt Beiträge zur Geschichte des Bundesheeres der 1. Republik von 1934-1938 Zusätzlich in der Printausgabe Walter Schilling Die Problematik der pazifistischen Grundströmung in Deutschland Hans Krech Die direkte Einflussnahme der strategischen Führungsebene von Al Qaida auf interne Konflikte in den Regionalorganisationen Heino Matzken Zwist statt Liebe in der Geburtskirche Ewiger christlicher Zankapfel auch Spielball im palästinensisch-israelischen Staatspoker! Klaus-Jürgen Bremm Die elektrische Telegraphie als Mittel militärischer Führung und der Nachrichtengewinnung in den deutschen Einigungskriegen sowie zahlreiche Berichte zur österreichischen und internationalen Verteidigungspolitik ÖMZ 4/2014-Online ÖMZ itärisc Mil he Z e ei h ts sc c i h h r Japan im Ersten Weltkrieg c i i f e t r r e t s Ö w Peer Revie Harald Pöcher 1808 er japanische Beitrag zum Ersten Weltkrieg Nation-starke Armee). Unmittelbar nach der Öffnung des führte zu einer Neugestaltung des westpazi- Landes gaben sich die ausländischen Militärdelegationen - Dfisch-ostasiatischen Raumes und schuf damit auch in der Hoffnung auf gute Geschäfte für ihre Rüstungs- -

The Oakhill Drive Volume 32 | July 2015

The Oakhill Drive volume 32 | july 2015 The Centenary of the Gallipoli Campaign 1915 – 2015 his year, 2015, marks one hundred years since the Gallipoli Campaign in World War I. The spirit of ANZAC has come to mean T many things for so many people over these past 100 Years. Next year, 2016, Oakhill College will celebrate 80 Years of Lasallian education in the Hills Region. During the course of our 80 Year history only one of our Alumni has died in the service of our country – Trooper Jason Brown (Class of 1999). In 2013 Jason was made an Alumni of Distinction (posthumously) in memorial of his life. Many hundreds of our Alumni have served or are still serving in our defence forces. As we pay tribute to all those many Australian men and women who have died in conflicts around the world over the past 100 years we would also like to recognise the achievements and on-going commitment to the service of this country by our Alumni. One such person is Colonel Kahlil Fegan. Kahlil Fegan graduated from Oakhill College in 1988 after commencing at the school eight years earlier in Grade 5. He studied for a Bachelor of Arts Degree at Newcastle University prior to graduating from the Royal Military College - Duntroon in 1993, to the Royal Australian Infantry Corps. He has served in a wide variety of roles in Australia, Canada, East Timor, Iraq and Afghanistan. Kahlil is currently serving as the Chief of Staff of the 1st Division/Deployable Joint Forces Headquarters. He is married to Ilona, an Organisational Development Manager and has two daughters, Caitlin and Lauren and a young son Elijah. -

September 2006 Vol

Registered by AUSTRALIA POST NO. PP607128/00001 ListeningListeningTHE AUGUST/SEPTEMBER 2006 VOL. 29 No.4 PostPost The official journal of THE RETURNED & SERVICES LEAGUE OF AUSTRALIA POSTAGE PAID SURFACE WA Branch Incorporated • PO Box Y3023 Perth 6832 • Established 1920 AUSTRALIA MAIL Viet-NamViet-Nam –– 4040 YearsYears OnOn Battle of Long-Tan Page 9 90th Anniversary – Annual Report Page 11 The “official” commencement date for the increased Australian commitment, this commitment “A Tribute to Australian involvement in Viet-Nam is set at 23 grew to involve the Army, Navy and Air Force as well May 1962, the date on which the (then) as civilian support, such as medical / surgical aid Minister for External Affairs announced the teams, war correspondents and officially sponsored Australia’s decision to send military instructors to entertainers. Vietnam. The first Australian troops At its peak in 1968, the Australian commitment Involvement in committed to Viet-Nam arrived in Saigon on amounted to some 83,000 service men and women. 3rd August 1962. This group of advisers were A Government study in 1977 identified some 59,036 Troops complete mission Viet-Nam collectively known as the “Australian Army males and 484 females as having met its definition of and depart Camp Smitty Training Team” (AATTV). “Viet-Nam Veterans”. Page 15 1962 – 1972 As the conflict escalated, so did pressure for Continue Page 5. 2 THE LISTENING POST August/September 2006 FULLY LOADED DEALS DRIVE AWAY NO MORE TO PAY $41,623* Metallic paint (as depicted) $240 extra. (Price applies to ‘05 build models) * NISSAN X-TRAIL ST-S $ , PATHFINDER ST Manual 40th Anniversary Special Edition 27 336 2.5 TURBO DIESEL PETROL AUTOMATIC 7 SEAT • Powerful 2.5L DOHC engine • Dual SRS airbags • ABS brakes • 128kW of power/403nm Torque • 3,000kg towing capacity PLUS Free alloy wheels • Free sunroof • Free fog lamps (trailer with brakes)• Alloy wheels • 5 speed automatic FREE ALLOY WHEEL, POWER WINDOWS * $ DRIVE AWAY AND LUXURY SEAT TRIM. -

South-West Pacific: Amphibious Operations, 1942–45

Issue 30, 2021 South-West Pacific: amphibious operations, 1942–45 By Dr. Karl James Dr. James is the Head of Military History, Australian War Memorial. Issue 30, 2021 © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print, and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice and imagery metadata) for your personal, non- commercial use, or use within your organisation. This material cannot be used to imply an endorsement from, or an association with, the Department of Defence. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Issue 30, 2021 On morning of 1 July 1945 hundreds of warships and vessels from the United States Navy, the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), and the Royal Netherlands Navy lay off the coast of Balikpapan, an oil refining centre on Borneo’s south-east coast. An Australian soldier described the scene: Landing craft are in formation and swing towards the shore. The naval gunfire is gaining momentum, the noise from the guns and bombs exploding is terrific … waves of Liberators [heavy bombers] are pounding the area.1 This offensive to land the veteran 7th Australian Infantry Division at Balikpapan was the last of a series amphibious operations conducted by the Allies to liberate areas of Dutch and British territory on Borneo. It was the largest amphibious operation conducted by Australian forces during the Second World War. Within an hour some 16,500 troops were ashore and pushing inland, along with nearly 1,000 vehicles.2 Ultimately more than 33,000 personnel from the 7th Division and Allied forces were landed in the amphibious assault.3 Balikpapan is often cited as an example of the expertise achieved by Australian forces in amphibious operations during the war.4 It was a remarkable development. -

SCOTTISH RECORD OFFICE Reels M584, M985-986

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT SCOTTISH RECORD OFFICE Reels M584, M985-986 Scottish Record Office HM General Register House 2 Princes Street Edinburgh EH1 3YY National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1964, 1976 CONTENTS Page 3 GD25 Kennedy Family, Earls of Cassillis 3 GD112 Campbell Family, Earls of Breadalbane 3 GD64 Campbell Family of Jura 4 GD18 Clerk Family of Penicuik 5 GD21 Cuninghame Family of Thorntoun 6 GD45 Dalhousie Papers 7 GD80 MacPherson Family of Cluny 7 GD68 Murray Family of Lintrose 8 GD1/395 Riddell Family of Ardnamurchan and Sunart 8 GD145 Robertson Family of Kindeace 8 GD46 Mackenzie Family, Earls of Saforth 9 GD1/471 New Blantyre, Lanarckshire 9 GD1/486 Andrew Rodger 9 GD51 Dundas Family of Melville 22 GD156 Elphinstone Family, Lords Elphinstone 23 GD161 Buchanan Family of Leny 23 GD219 Murray Family of Murraythwaite 23 GD232 Fraser, Stoddart and Ballingall of Edinburgh 24 GD240 Bruce and Kerr 24 GD248 Ogilvy Family, Earls of Seafield Note: The name of the Scottish Record Office was changed to the National Archives of Scotland in 1999. In 2011 it merged with the General Register Office for Scotland to form National Records of Scotland. 2 SCOTTISH RECORD OFFICE Reel M584 GD25 Papers of the Kennedy Family, Earls of Cassillis (Ailsa Muniments), c 1290-1940 Archibald Kennedy (1770-1846), 12th Earl of Cassillis (succeeded 1794), 1st Baron Ailsa (created 1806), 1st Marquess of Ailsa (created 1831). GD25/9 Miscellaneous papers 42 Letters: business and estate matters, 1793-1848 Select: 13 John Hutchinson (HMS Captivity) to Lord Cassillis, 19 June 1811: gift of model of Tower of David at Jerusalem; Lord Cassillis’s kindness during Hutchison’s misfortunes. -

Revisiting and Early Naval Incident of the Cold War: Archaeological Identification of the Bow of HMS Volage Sunk During the Corf

Notes 1 During the 2008 field season the bay of Porto Polermo and its entrance was completed. 2 Multibeam data was acquired through Kongsberg’s SIS software, processed in CARIS HIPS/SIPS, and modeled in IVS Fledermaus software for anomaly analysis. All acquisition and processing of data was performed by surveyors contracted from Highland Geo Solutions Inc. of Fredericton, NB, Canada. 3 IVS kindly provided a prototype software module that allowed the tracking of all vessels within James P. Delgado INA the 3-D models of the seafloor in Jeffery Royal RPM Nautical Foundation Fledermaus. Adrian Anastasi University of Tirana 4 Although it is not clear from the evidence if this was the scuttled Austro-Hungarian submarine U-72, the German U-24, or whether a Revisiting and Early Naval Incident of the Cold British submarine (possibly the H2) that was also lost in the area. War: Archaeological Identification of the Bow 5 Not only were modern war craft a common find, but a spent of HMS Vol ag e Sunk During the Corfu missile was also found in target confirmation. There have been Channel Incident of October 22, 1946 many tons of munitions from the HMS Volage, various 20th-century conflicts from Pingbosun, removed from Montengro’s waters Destroyers by the RDMC; however, all of the Second Album, finds discussed here were at depths Picasa. over 60 m. 6 The heavy concentration of Roman and Late Roman-era amphoras littering the seafloor, some of which are intrusive on Archaic-Hellenist Greek wreck sites, probably led to confusion. 7 Lindhagen 2009. -

We Envy No Man on Earth Because We Fly. the Australian Fleet Air

We Envy No Man On Earth Because We Fly. The Australian Fleet Air Arm: A Comparative Operational Study. This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Murdoch University 2016 Sharron Lee Spargo BA (Hons) Murdoch University I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………………………………………………………………….. Abstract This thesis examines a small component of the Australian Navy, the Fleet Air Arm. Naval aviators have been contributing to Australian military history since 1914 but they remain relatively unheard of in the wider community and in some instances, in Australian military circles. Aviation within the maritime environment was, and remains, a versatile weapon in any modern navy but the struggle to initiate an aviation branch within the Royal Australian Navy was a protracted one. Finally coming into existence in 1947, the Australian Fleet Air Arm operated from the largest of all naval vessels in the post battle ship era; aircraft carriers. HMAS Albatross, Sydney, Vengeance and Melbourne carried, operated and fully maintained various fixed-wing aircraft and the naval personnel needed for operational deployments until 1982. These deployments included contributions to national and multinational combat, peacekeeping and humanitarian operations. With the Australian government’s decision not to replace the last of the aging aircraft carriers, HMAS Melbourne, in 1982, the survival of the Australian Fleet Air Arm, and its highly trained personnel, was in grave doubt. This was a major turning point for Australian Naval Aviation; these versatile flyers and the maintenance and technical crews who supported them retrained on rotary aircraft, or helicopters, and adapted to flight operations utilising small compact ships.