1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Application for the Newcastle Schools 16 to 19 Bursary Fund 2011/2012

16 to 19 Bursary Fund 2020/21 for North Tyneside Schools Application form and guidance If you are starting Year 12, 13 or 14 at a North Tyneside school in September 2020, you might be entitled to a bursary to help with costs during term time. Read inside for details. Please note that we can provide information in other formats such as large print or Braille. 1. What is the 16 to 19 School Bursary Fund? The 16 to 19 Bursary Fund provides financial help to young people aged 16 to 19 who face financial barriers to participating in education or training, provided they meet agreed standards of attendance, behaviour and progress. In North Tyneside, all secondary schools with a sixth form have agreed a joint scheme called the 16 to 19 Bursary Fund for North Tyneside Schools’. The scheme is being administered on behalf of schools by North Tyneside Council and is dependent on funding received from the Government. Other post-16 providers in North Tyneside and the surrounding area are operating their own bursary schemes and will be able to give you further information on their arrangements. Receipt of bursary funding does not affect other means-tested benefits paid to families. 2. Who is eligible for the bursary scheme? To be eligible, you must: • Attend a participating school/Local Authority provider in North Tyneside which is part of the scheme (see page 3 for a list) • Be starting Year 12, 13 or 14 in September 2020 • Be aged between 16 and 18 on 31 August 2020 In addition, there are eligibility criteria for the different levels of bursary available. -

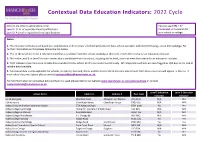

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

Proposed Co-Ordinated Admissions Scheme for Middle and High Schools in the Area of North Tyneside Local Authority 2022

Appendix 2 Proposed Co-ordinated Admissions Scheme for Middle and High Schools in the area of North Tyneside Local Authority 2022 Introduction 1. This Scheme is made by North Tyneside Council under the Education (Co-ordination of Admission Arrangements) (Primary) (England) Regulations 2008 and applies to all Middle and High Schools in North Tyneside. Interpretation 2. In this Scheme - "The LA" means North Tyneside Council acting in their capacity as Local Authority; "The LA area" means the area in respect of which the LA is the Local Authority; "Primary education" has the same meaning as in section 2(1) of the Education Act 1996; "Secondary education" has the same meaning as in section 2(2) of the Education Act 1996; "Primary school" has the same meaning as in section 5(1) of the Education Act 1996; "Secondary school" has the same meaning as in section 5(2) of the Education Act 1996; "School" means a community, foundation or voluntary school (but not a special school), which is maintained by the LA; 'VA schools" means such of the schools as are voluntary aided schools; “Trust schools” means such of the schools have a trust status; “Academy” means such of the schools have academy status; "Admission Authority" in relation to a community school means the LA and, in relation to Trust and VA schools means the governing body of that school and in relation to an Academy means the Academy Trust of that school. “The equal preference system” the scheme operated by North Tyneside Council whereby all preferences listed by parents/carers on the common application form are considered under the over-subscription criteria for each school without reference to parental rankings. -

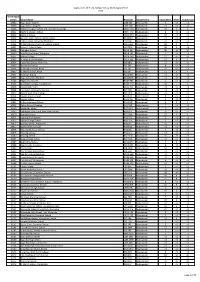

Eligible If Taken A-Levels at This School (Y/N)

Eligible if taken GCSEs Eligible if taken A-levels School Postcode at this School (Y/N) at this School (Y/N) 16-19 Abingdon 9314127 N/A Yes 3 Dimensions TA20 3AJ No N/A Abacus College OX3 9AX No No Abbey College Cambridge CB1 2JB No No Abbey College in Malvern WR14 4JF No No Abbey College Manchester M2 4WG No No Abbey College, Ramsey PE26 1DG No Yes Abbey Court Foundation Special School ME2 3SP No N/A Abbey Gate College CH3 6EN No No Abbey Grange Church of England Academy LS16 5EA No No Abbey Hill Academy TS19 8BU Yes N/A Abbey Hill School and Performing Arts College ST3 5PR Yes N/A Abbey Park School SN25 2ND Yes N/A Abbey School S61 2RA Yes N/A Abbeyfield School SN15 3XB No Yes Abbeyfield School NN4 8BU Yes Yes Abbeywood Community School BS34 8SF Yes Yes Abbot Beyne School DE15 0JL Yes Yes Abbots Bromley School WS15 3BW No No Abbot's Hill School HP3 8RP No N/A Abbot's Lea School L25 6EE Yes N/A Abbotsfield School UB10 0EX Yes Yes Abbotsholme School ST14 5BS No No Abbs Cross Academy and Arts College RM12 4YB No N/A Abingdon and Witney College OX14 1GG N/A Yes Abingdon School OX14 1DE No No Abraham Darby Academy TF7 5HX Yes Yes Abraham Guest Academy WN5 0DQ Yes N/A Abraham Moss Community School M8 5UF Yes N/A Abrar Academy PR1 1NA No No Abu Bakr Boys School WS2 7AN No N/A Abu Bakr Girls School WS1 4JJ No N/A Academy 360 SR4 9BA Yes N/A Academy@Worden PR25 1QX Yes N/A Access School SY4 3EW No N/A Accrington Academy BB5 4FF Yes Yes Accrington and Rossendale College BB5 2AW N/A Yes Accrington St Christopher's Church of England High School -

School Name POSTCODE AUCL Eligible If Taken GCSE's at This

School Name POSTCODE AUCL Eligible if taken GCSE's at this AUCL Eligible if taken A-levels at school this school City of London School for Girls EC2Y 8BB No No City of London School EC4V 3AL No No Haverstock School NW3 2BQ Yes Yes Parliament Hill School NW5 1RL No Yes Regent High School NW1 1RX Yes Yes Hampstead School NW2 3RT Yes Yes Acland Burghley School NW5 1UJ No Yes The Camden School for Girls NW5 2DB No No Maria Fidelis Catholic School FCJ NW1 1LY Yes Yes William Ellis School NW5 1RN Yes Yes La Sainte Union Catholic Secondary NW5 1RP No Yes School St Margaret's School NW3 7SR No No University College School NW3 6XH No No North Bridge House Senior School NW3 5UD No No South Hampstead High School NW3 5SS No No Fine Arts College NW3 4YD No No Camden Centre for Learning (CCfL) NW1 8DP Yes No Special School Swiss Cottage School - Development NW8 6HX No No & Research Centre Saint Mary Magdalene Church of SE18 5PW No No England All Through School Eltham Hill School SE9 5EE No Yes Plumstead Manor School SE18 1QF Yes Yes Thomas Tallis School SE3 9PX No Yes The John Roan School SE3 7QR Yes Yes St Ursula's Convent School SE10 8HN No No Riverston School SE12 8UF No No Colfe's School SE12 8AW No No Moatbridge School SE9 5LX Yes No Haggerston School E2 8LS Yes Yes Stoke Newington School and Sixth N16 9EX No No Form Our Lady's Catholic High School N16 5AF No Yes The Urswick School - A Church of E9 6NR Yes Yes England Secondary School Cardinal Pole Catholic School E9 6LG No No Yesodey Hatorah School N16 5AE No No Bnois Jerusalem Girls School N16 -

State-Funded Schools, England1 LAESTAB School

Title: State-funded schools1, who had a decrease in the attainment gap2,3 between white males4 who were and were not eligible for free school meals (FSM)5 achieving A*-C/9-4 in English and maths6,7, between 2014/15 and 2016/17 8 Years: 2014/15 and 2016/17 8 Coverage: State-funded schools, England1 LAESTAB School name 3526908 Manchester Enterprise Academy 3364113 Highfields School 8784120 Teignmouth Community School, Exeter Road 3186907 Richmond Park Academy 2046906 The Petchey Academy 8874174 Greenacre School 3594501 The Byrchall High School 3554620 All Hallows RC High School 9084135 Treviglas Community College 9194117 The Sele School 8934501 Ludlow Church of England School 9096908 Furness Academy 8904405 St George's School A Church of England Academy 8104622 Hull Trinity House Academy 3844023 Ossett Academy and Sixth Form College 8084002 St Michael's Catholic Academy 3924038 John Spence Community High School 3703326 Holy Trinity 3934019 Boldon School 8504002 The Costello School 8884405 Central Lancaster High School 2084731 The Elmgreen School 9094150 Dowdales School 9084001 Fowey River Academy 8074005 Laurence Jackson School 3024012 Whitefield School 9314120 Cheney School 3724601 Saint Pius X Catholic High School A Specialist School in Humanities 9364508 Esher Church of England High School 8865461 St John's Catholic Comprehensive 3096905 Greig City Academy 3545402 Kingsway Park High School 8614038 The Excel Academy 3314005 Stoke Park School and Community Technology College 9354033 Mildenhall College Academy 3014024 Eastbury Community -

Update on Behaviour Management And

Briefing note Meeting: Children, Education and Skills Sub-committee Date: 12th September 2019 Title: Behaviour and exclusions in the borough Author: Lisa Rodgers and Anne Oldham Tel: 643 8500 Service: Early Years and School Improvement Service Wards affected: All 1. Purpose of Report The purpose of this report is to update committee members on the most recent information, patterns and trends in behaviour and exclusions of pupils. 2. Recommendations The sub-committee is recommended to note the contents of this report. 3. Headlines 3.1. Across the last school year, the Keeping Children in School agenda has remained a focus for headteachers, school staff and local authority colleagues working with children and families. 3.2. The numbers of fixed-term and permanent exclusions, including pupils who are looked after (LAC) and those who have a special educational need or disability (SEND) continues to be well below the national average. 3.3. The challenging behaviour of pupils in primary schools has been addressed effectively through the Primary Outreach Team. This has resulted in more pupils up to the age of 11 remaining in school. 3.4. Changes in the fair access, attendance and placement panels have resulted in a more efficient approach to managing support for secondary schools and students. 3.5. Through the introduction of a graduated response, schools and settings have been supported to follow a common framework which provides appropriately staged support to pupils’ individual needs. 3.6. Officer gatekeeping of all exclusion referrals by the student support team, including pupils entering and leaving Moorbridge and PALs, has brought a higher level of consistency of documentation, scrutiny, challenge and monitoring or pupils moving around the system. -

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2018 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 6 <3 <3 10006 Ysgol Gyfun Llangefni LL77 7NG Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 10 3 3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 8 <3 <3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 17 <3 <3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained <3 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 10 3 3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 29 3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 30 10 10 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained 5 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 11 <3 <3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 15 4 4 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent <3 <3 <3 10036 The Marist School SL5 7PS Independent 4 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent <3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 11 5 4 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained <3 <3 <3 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained 6 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 30 7 5 10046 Didcot Sixth Form OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10053 Oxford Sixth Form College OX1 4HT Independent <3 <3 -

List of North East Schools

List of North East Schools This document outlines the academic and social criteria you need to meet depending on your current secondary school in order to be eligible to apply. For APP City/Employer Insights: If your school has ‘FSM’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling. If your school has ‘FSM or FG’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling or be among the first generation in your family to attend university. For APP Reach: Applicants need to have achieved at least 5 9-5 (A*-C) GCSES and be eligible for free school meals OR first generation to university (regardless of school attended) Exceptions for the academic and social criteria can be made on a case-by-case basis for children in care or those with extenuating circumstances. Please refer to socialmobility.org.uk/criteria-programmes for more details. If your school is not on the list below, or you believe it has been wrongly categorised, or you have any other questions please contact the Social Mobility Foundation via telephone on 0207 183 1189 between 9am – 5:30pm Monday to Friday. School or College Name Local Authority Academic Criteria Social Criteria Acklam Grange School Middlesbrough 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints Academy Stockton-On-Tees 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Ashington Academy Northumberland 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Astley Community High School Northumberland 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Bede Academy Northumberland 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Bedlington Academy Northumberland 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Belmont Community School County Durham 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Benfield School Newcastle Upon Tyne 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Berwick Academy Northumberland 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Biddick Academy Sunderland 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Bishop Auckland College County Durham Please check your Please check your secondary school. -

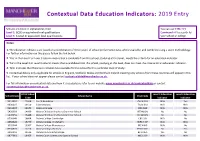

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2019 Entry

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2019 Entry Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. UCAS School Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Code School Name Post Code Code Indicator Indicator 9314901 12474 16-19 Abingdon OX14 1JB N/A Yes 9336207 19110 3 Dimensions TA20 3AJ N/A N/A 9316007 15144 Abacus College OX3 9AX -

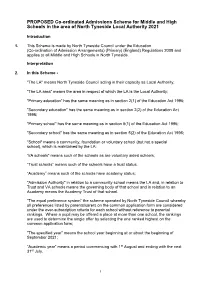

PROPOSED Co-Ordinated Admissions Scheme for Middle and High Schools in the Area of North Tyneside Local Authority 2021

PROPOSED Co-ordinated Admissions Scheme for Middle and High Schools in the area of North Tyneside Local Authority 2021 Introduction 1. This Scheme is made by North Tyneside Council under the Education (Co-ordination of Admission Arrangements) (Primary) (England) Regulations 2008 and applies to all Middle and High Schools in North Tyneside. Interpretation 2. In this Scheme - "The LA" means North Tyneside Council acting in their capacity as Local Authority; "The LA area" means the area in respect of which the LA is the Local Authority; "Primary education" has the same meaning as in section 2(1) of the Education Act 1996; "Secondary education" has the same meaning as in section 2(2) of the Education Act 1996; "Primary school" has the same meaning as in section 5(1) of the Education Act 1996; "Secondary school" has the same meaning as in section 5(2) of the Education Act 1996; "School" means a community, foundation or voluntary school (but not a special school), which is maintained by the LA; 'VA schools" means such of the schools as are voluntary aided schools; “Trust schools” means such of the schools have a trust status; “Academy” means such of the schools have academy status; "Admission Authority" in relation to a community school means the LA and, in relation to Trust and VA schools means the governing body of that school and in relation to an Academy means the Academy Trust of that school. “The equal preference system” the scheme operated by North Tyneside Council whereby all preferences listed by parents/carers on the common application form are considered under the over-subscription criteria for each school without reference to parental rankings. -

All Champion Schools for Website

Region URN School name 2018/19 Award All Saints Academy EA1 135946 Dunstable Gold EA1 109707 Ashcroft High School Bronze EA1 121164 Aylsham High School Bronze EA1 138274 Beccles Free School Gold EA1 138228 Bedford Free School Gold EA1 109727 Bedford Girls' School Gold Cardinal Newman Catholic School A EA1 142310 Specialist Science College Gold EA1 138162 Castle Manor Academy Bronze EA1 137462 Cedars Upper School Bronze Challney High School for EA1 136651 Boys Bronze EA1 138373 Chantry Academy Bronze EA1 144214 Claydon High School Bronze Coleridge Community EA1 136650 College Silver Downham Market EA1 145196 Academy Bronze EA1 137218 East Bergholt High School Bronze EA1 137632 Etonbury Academy Gold Greater Peterborough EA1 142902 UTC Silver EA1 136271 Hartismere School Silver EA1 137475 Hinchingbrooke School Silver EA1 139311 Hobart High School Bronze EA1 137208 Holbrook Academy Bronze EA1 138569 Houghton Regis Academy Silver EA1 137679 Icknield High School Gold EA1 138250 IES Breckland Gold EA1 140047 Ixworth Free School Gold EA1 145271 Jack Hunt School Silver Kempston Challenger EA1 142387 Academy Silver King Edward VI CofE Voluntary Controlled EA1 124856 Upper School Bronze Lea Manor High School EA1 109709 Performing Arts College Bronze EA1 109686 Lealands High School Silver EA1 136992 Longsands Academy Silver EA1 144342 Manshead CofE Academy Gold EA1 142396 Marshland High School Silver EA1 137082 Nene Park Academy Gold Region URN School name 2018/19 Award EA1 140669 Newmarket Academy Bronze North Cambridge EA1 139401 Academy Bronze