Re-Performance & Otherwise Movements Adam Kinner a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rapport Annuel 18/19

RAPPORT ANNUEL 2018-2019 SOMMAIRE TABLE OF CONTENTS LES GRANDS BALLETS 4 LES GRANDS BALLETS MOT DU PRÉSIDENT 6 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT HISTORIQUE DES GRANDS BALLETS 8 HISTORY OF LES GRANDS BALLETS LES GRANDS BALLETS EN CHIFFRES 12 LES GRANDS BALLETS AT A GLANCE SAISON 2018-2019 16 2018-2019 SEASON MUSIQUE ET CHANT 18 MUSIC AND SONG LE BALLET NATIONAL DE POLOGNE 21 THE POLISH NATIONAL BALLET RAYONNEMENT INTERNATIONAL 23 INTERNATIONAL CELEBRITY LA FAMILLE CASSE-NOISETTE 26 THE NUTCRACKER FAMILY CENTRE NATIONAL DE DANSE-THÉRAPIE 28 NATIONAL CENTRE FOR DANCE THERAPY LES STUDIOS 30 GALA-BÉNÉFICE 2018 35 2018 ANNUAL BENEFIT GALA LES JEUNES GOUVERNEURS 36 THE JEUNES GOUVERNEURS COMMANDITAIRES ET PARTENAIRES 38 SPONSORS AND PARTNERS REMERCIEMENTS 39 SPECIAL THANKS Photo: Sasha Onyshchenko • Danseuse / Dancer: Maude Sabourin DANSEURS 45 DANCERS 3 LES GRANDS BALLETS FAIRE BOUGER LE MONDE. AUTREMENT. Depuis plus de 60 ans, Les Grands Ballets Canadiens de Montréal sont une compagnie de création, de production et de diffusion internationale qui se consacre au développement de la danse sous toutes ses formes, en s’appuyant sur la discipline du ballet classique. Les danseuses et danseurs des Grands Ballets, sous la direction artistique d’Ivan Cavallari, interprètent des chorégraphies de créateurs de référence et d’avant-garde. Les Grands Ballets, reconnus pour leur excellence, leur créativité et leur audace, sont pleinement engagés au sein de la collectivité et rayonnent sur toutes les scènes du monde. MOVING THE WORLD. DIFFERENTLY. For over 60 years, Les Grands Ballets Canadiens de Montréal has been a creation, production and international performance company devoted to the development of dance in all its forms, while always staying faithful to the spirit of classical ballet. -

Dis/Counting Women: a Critical Feminist Analysis of Two Secondary Social Studies Textbooks

DIS/COUNTING WOMEN: A CRITICAL FEMINIST ANALYSIS OF TWO SECONDARY SOCIAL STUDIES TEXTBOOKS by JENNIFER TUPPER B.Ed., The University of Alberta, 1994 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF CURRICULUM STUDIES; FACULTY OF EDUCATION; SOCIAL STUDIES SPECIALIZATION We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September 1998 ©Copyright: Jennifer Tupper, 1998 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Curriculum Studies The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date October ff . I 9 92? 11 ABSTRACT Two secondary social studies textbooks, Canada: A Nation Unfolding, and Canada Today were analyzed with regard to the inclusion of the lives, experiences, perspectives and contributions of females throughout history and today. Drawing on the existing literature,-a framework of analysis was created comprised of four categories: 1) language; 2) visual representation; 3) positioning and; 4) critical analysis of content. Each of these categories was further broken into a series of related subcategories in order to examine in depth and detail, the portrayal of women in these two textbooks. -

Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation

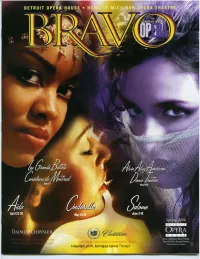

2006 Spring Opera Season is sponsored by Cadillac Copyright 2010, Michigan Opera Theatre LaSalle Bank salutes those who make the arts a part of our lives. Personal Banking· Commercial Banking· Wealth Management Making more possible LaSalle Bank ABN AMRO ~ www. la sal lebank.com t:.I Wealth Management is a division of LaSalle Bank, NA Copyright 2010,i'ENm Michigan © 2005 LaSalle Opera Bank NTheatre.A. Member FDIC. Equal Opportunity Lender. 2006 The Official MagaZine of the Detroit Opera House BRAVO IS A MICHI GAN OPERA THEAT RE P UB LI CATION Sprin",,---~ CONTRI BUTORS Dr. David DiChiera Karen VanderKloot DiChiera eason Roberto Mauro Michigan Opera Theatre Staff Dave Blackburn, Editor -wELCOME P UBLISHER Letter from Dr. D avid DiChiera ...... .. ..... ...... 4 Live Publishing Company Frank Cucciarre, Design and Art Direction ON STAGE Bli nk Concept &: Design, Inc. Production LES GRAND BALLETS CANADIENS de MONTREAL .. 7 Chuck Rosenberg, Copy Editor Be Moved! Differently . ............................... ... 8 Toby Faber, Director of Advertising Sales Physicians' service provided by Henry Ford AIDA ............... ..... ...... ... .. ... .. .... 11 Medical Center. Setting ................ .. .. .................. .... 12 Aida and the Detroit Opera House . ..... ... ... 14 Pepsi-Cola is the official soft drink and juice provider for the Detroit Opera House. C INDERELLA ...... ....... ... ......... ..... .... 15 Cadillac Coffee is the official coffee of the Detroit Setting . ......... ....... ....... ... .. .. 16 Opera House. Steinway is the official piano of the Detroit Opera ALVIN AILEY AMERICAN DANCE THEATER .. ..... 17 House and Michigan Opera Theatre. Steinway All About Ailey. 18 pianos are provided by Hammell Music, exclusive representative for Steinway and Sons in Michigan. SALOME ........ ... ......... .. ... ... 23 President Tuxedo is the official provider of Setting ............. .. ..... .......... ..... 24 formal wear for the Detroit Opera House. -

Cultural Diplomacy and Nation-Building in Cold War Canada, 1945-1967 by Kailey Miller a Thesis Submitt

'An Ancillary Weapon’: Cultural Diplomacy and Nation-building in Cold War Canada, 1945-1967 by Kailey Miller A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in History in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September, 2015 Copyright ©Kailey Miller, 2015 Abstract This dissertation is a study of Canada’s cultural approaches toward the Communist world – particularly in the performing arts – and the ways in which the public and private sectors sought to develop Canada’s identity during the Cold War. The first chapter examines how the defection of Igor Gouzenko in 1945 framed the Canadian state’s approach to the security aspects of cultural exchanges with the Soviet Union. Chapters 2 to 4 analyse the socio-economic, political, and international context that shaped Canada's music, classical theatre, and ballet exchanges with communist countries. The final chapter explores Expo ’67’s World Festival of Arts and Entertainment as a significant moment in international and domestic cultural relations. I contend that although focused abroad, Canada’s cultural initiatives served a nation-building purpose at home. For practitioners of Canadian cultural diplomacy, domestic audiences were just as, if not more, important as foreign audiences. ii Acknowledgements My supervisor, Ian McKay, has been an unfailing source of guidance during this process. I could not have done this without him. Thank you, Ian, for teaching me how to be a better writer, editor, and researcher. I only hope I can be half the scholar you are one day. A big thank you to my committee, Karen Dubinsky, Jeffrey Brison, Lynda Jessup, and Robert Teigrob. -

University Musical Society

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY Les Grands Ballets Canadians COPPELIA(1870) Saturday Evening, October 17, 1992, at 8:00 Sunday Afternoon, October 18, 1992, at 3:00 Power Center for the Performing Arts Ann Arbor, Michigan Choreography: Enrique Martinez after Marius Petipa Music: Leo Delibes Sets and Costumes: Peter Home Costumes Design Collaborator: Lydia Randolph Lighting: Nicholas Cernovitch Act I A village square The action evolves around Coppelia, the beautiful but enigmatic young daughter of Dr. Coppelius. Swanilda suspects her fiance, Frantz, of harboring a secret love for Coppelia. The burgermeister announces that tomorrow he will distribute dowries to the engaged couples of the village and urges Swanilda to wed Frantz. But possessed by jealousy, Swanilda breaks off the engagement. Night falls and the crowd disperses. As Coppelius leaves his house, he is jostled by a group of young men and drops his key. Swanilda finds the key and enters the forbidden house with her friends. Frantz, too, is attempting to enter the house when Coppelius returns unexpectedly. Act II Coppelius' workshop peopled with curious figures The young women overcome their initial timidity and boldly make their way through the house. Swanilda quickly discovers to her joy that Coppelia is only a mechanical doll. At this point, Coppelius suddenly appears and chases out the intruders, all but Swanilda who, hidden behind the curtain, takes the place of Coppelia. Coming upon Frantz, who has finally gotten into the house, Coppelius makes him drink a potion intended to pull the young man's vital force from his body and transfer it to the doll. -

20 Years of Inspiration

20 years of inspiration The arts engage and inspire us 20 years of inspiration National Arts Centre | Ottawa | May 5, 2012 20 years of inspiration Welcome to the 20th anniversary Governor General’s In 2007 the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) Performing Arts Awards Gala! joined the Awards Foundation as a creative partner, and agreed to produce a short film about each Award The Governor General’s Performing Arts Awards recipient (beginning with the 2008 laureates). After (GGPAA) were created in 1992 under the patronage of the late Right Honourable Ramon John Hnatyshyn premiering at the GGPAA Gala, these original and (1934–2002), 24th Governor General of Canada, engaging films are made available to all Canadians and his wife Gerda. on the Web and in a variety of digital formats. The idea for the GGPAA goes back to the late 2008 marked the launch of the GGPAA Mentorship 1980s and a discussion between Peter Herrndorf Program, a unique partnership between the Awards (now President and CEO of the National Arts Centre) Foundation and the National Arts Centre that pairs and entertainment industry executive Brian Robertson, a past award recipient with a talented artist in both of whom were involved at the time with the mid-career. (See page 34.) Toronto Arts Awards Foundation. When they “The Governor General’s Performing Arts Awards approached Governor General Hnatyshyn with are the highest tribute we can offer Canadian artists,” their proposal for a national performing arts awards said Judith LaRocque, former Deputy Minister of program, they received his enthusiastic support. Canadian Heritage and former Secretary to the “He became a tremendous fan of the artists receiving Governor General, in an interview on the occasion the awards each year, the perfect cheerleader in the of the 15th anniversary of the Awards. -

Femmes Du Plateau

ASSEMBLÉE GÉNÉRALE ANNUELLE SHP Mercredi ______________________________________________ 29 avril 2015 Printemps 2015 – Vol. 10, no 1 – www.histoireplateau.org (voir p. 2) Femmes du Plateau Robertine Barry 1863-1910 Gaëtane de Montreuil 1867-1951 Marie Lacoste Gérin-Lajoie 1867-1945 Éva Circé-Côté 1871-1949 Idola St-Jean 1880-1945 Madame Jean-Louis Audet 1889-1970 Marie Gérin-Lajoie 1890-1971 Thérèse Casgrain 1896-1981 Dolorès Riopel 1923-2015 Ludmilla Chiriaeff 1924-1996 Annette Nolin 1924-1993 Maureen Forrester 1930-2010 ÉVÉNEMENTS / PROJETS de la Société d’histoire du Plateau-Mont-RoyaL MERCI DOLORÈS RIOPEL CONGRÈS HISTOIRE QUÉBEC (1923-2015) 2015 e Chère sœur Dolorès, LE CONGRÈS du 50 anniversaire de la Fédération Histoire Québec aura lieu Aujourd’hui, 2 février 2015, les les 15, 16 et 17 mai 2015 à Rivière- membres de la Société d’histoire du-Loup. Le président de la Société du Plateau-Mont-Royal ont le d’histoire du Plateau-Mont-Royal, cœur lourd suite à votre départ. M. Richard Ouellet, récipiendaire Votre présence parmi nous au 2014 du Prix Honorius-Provost conseil d’administration de la pour le bénévolat, aura le privilège société pendant les premières de participer au jury de sélection de années de son existence nous l’édition 2015. a largement inspirés. Nous avions une passion commune pour l’histoire et la cueillette de témoignages. Mais surtout, nous DU SANG NEUF À LA étions fiers de côtoyer une femme de SOCIÉTÉ D’HISTOIRE : l’Institut Notre-Dame du Bon-Conseil vouée à l’action sociale. LOUIS SENÉCAL, CONSEILLER Marie Gérin-Lajoie avait raison quand elle EN INFORMATIQUE vous a dit lors de votre entrée en communauté en 1951 : « Vous en ferez des choses ». -

MISE EN CANDIDATURE Publication Produite Par Le Secrétariat Général Du Ministère De La Culture, Des Communications Et De La Condition Féminine

DOMAINE CULTUREL MISE EN CANDIDATURE Publication produite par le Secrétariat général du ministère de la Culture, des Communications et de la Condition féminine CONCEPTION GRAPHIQUE Communication Publi Griffe IMPRESSION Imprimerie Bourg-Royal inc. CRÉDITS PHOTOGRAPHIQUES Athanase David Archives nationales du Québec Paul-Émile Borduas Office national du film Denise Pelletier Studio Zarov Albert Tessier Archives nationales du Québec Gérard Morisset Archives nationales du Québec Georges-Émile Lapalme Éditeur officiel du Québec Dépôt légal : 2008 Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec Bibliothèque et Archives Canada ISBN : 2-550-51940-9 (version imprimée) ISBN : 2-550-51941-6 (PDF) © Gouvernement du Québec, 2008 MOT DE LA MINISTRE Le Québec est riche d’une culture originale reconnue à travers le monde. Celles et ceux qui lui donnent vie et qui assurent son rayonne- ment méritent la plus haute reconnaissance de la part de notre collectivité. Chaque année, les Prix du Québec récompensent l’apport de ces hommes et de ces femmes d’exception qui, par leur talent et leur générosité, se sont signalés dans un domaine lié à la culture. Il vous appartient, citoyennes et citoyens, autant qu’organismes et institutions, de faire connaître les personnes de votre entourage qui se distinguent par la qualité et la constance de leurs réalisations. Je vous invite à concrétiser votre admiration envers ces personnes en propo- sant leur candidature aux Prix du Québec 2008 et ainsi permettre leur intronisation éventuelle au panthéon des personnages illustres de notre histoire culturelle tels les Athanase David, Paul-Émile Borduas, Albert Tessier, Gérard Morisset, Denise Pelletier et Georges-Émile Lapalme. -

Chiriaeff : Danser Pour Ne Pas Mourir Comprend Des Réf

B iographie De la même auteure La place de la femme dans le Québec de 1967, Éditions Étendard, St-Jérôme, hiver 1967. La notion de service essentiel en droit du travail québécois ou l’impossible définition, dans «25 ans de pratique en relation industrielles», C.R.I., 1990. De la Curatelle au Curateur public, 50 ans de protection, Presses de l’Université du Québec, Québec, 1995. Justine Lacoste-Beaubien et l’Hôpital Sainte-Justine, en collaboration, Presses HEC, Presses de l’Université du Québec, Québec, 1995. Catalogage avant publication de Bibliothèque et Archives Canada Forget, Nicolle Ludmilla Chiriaeff : danser pour ne pas mourir Comprend des réf. bibliogr. et un index. ISBN 978-2-7644-0431-7 (Version imprimée) ISBN 978-2-7644-1456-9 (PDF) ISBN 978-2-7644-1816-1 (EPUB) 1. Chiriaeff, Ludmilla, 1924-1996. 2. Grands ballets canadiens - Histoire. 3. Danseurs de ballet - Québec (Province) - Biographies. 4. Chorégraphes - Québec (Province) - Biographies. I. Titre. GV1785.C55F67 2006 792.802'8'092 C2005-942111-8 Nous reconnaissons l’aide financière du gouvernement du Canada par l’entremise du Programme d’aide au développement de l’industrie de l’édition (PADIÉ) pour nos activités d’édition. Gouvernement du Québec – Programme de crédit d’impôt pour l’édition de livres – Gestion SODEC. Les Éditions Québec Amérique bénéficient du programme de subvention globale du Conseil des Arts du Canada. Elles tiennent également à remercier la SODEC pour son appui financier. Québec Amérique 329, rue de la Commune Ouest, 3e étage Montréal (Québec) Canada H2Y 2E1 Tél.: 514 499-3000, télécopieur: 514 499-3010 Dépôt légal : 2e trimestre 2006 Bibliothèque nationale du Québec Bibliothèque nationale du Canada ISBN 10 : 2-7644-0428-X ISBN 13 : 978-2-7644-0428-7 Mise en pages : André Vallée – Atelier typo Jane Révision linguistique : Diane Martin Conception graphique : Isabelle Lépine Tous droits de traduction, de reproduction et d’adaptation réservés ©2006 Éditions Québec Amérique inc. -

Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage

Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage CHPC Ï NUMBER 048 Ï 2nd SESSION Ï 41st PARLIAMENT EVIDENCE Monday, May 25, 2015 Chair Mr. Gordon Brown 1 Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage Monday, May 25, 2015 Ï (1530) It's exactly the same thing that we are advocating now. Over these [English] 12 years, we have tested this experience. I didn't really think that The Chair (Mr. Gordon Brown (Leeds—Grenville, CPC)): 12 years later, I myself would be able to talk about the success and, Good afternoon, everyone. above all, the results that we have achieved through this program which, fundamentally brings about what I call cultural knowledge We'll call to order meeting number 48 of the Standing Committee transfer, which would not have happened otherwise without the on Canadian Heritage. Today we are continuing our study of dance artistic work to compel them, by testifying and testing them. in Canada. For the first hour we have with us three different groups. That's what we did by addressing this from a philosophic and First we have Zab Maboungou, artistic director of Zab technical perspective, in that we had to put forward a technique for Maboungou/Compagnie Danse Nyata Nyata. movement that could operate these transfers. Today, there are trained [Translation] individuals who are working and who choose, while continuing their We also have with us Anik Bissonnette, artistic director, and artistic career, to seek professional development in the arts of health, Alix Laurent, executive director, of the École supérieure de ballet du reflection, and arts management, and other fields. -

2011 Gala Program

2011 GOVERNOR GENERAL’S PERFORMING ARTS AWARDS GALA The arts engage and inspire us 2011 GOVERNOR GENERAL’S PERFORMING ARTS AWARDS GALA Presented by National Arts Centre Ottawa May 14, 2011 The Governor General’s Performing Arts Awards The Governor General’s Performing Arts Awards are Recipients of the National Arts Centre (NAC) Award, Canada’s most prestigious honour in the performing arts. which recognizes work of an extraordinary nature in the Created in 1992 by the late Right Honourable Ramon John previous performance year, are selected by a committee Hnatyshyn (1934–2002), then Governor General of Canada, of senior NAC programmers. This Award comprises a and his wife Gerda, the Awards are the ultimate recognition $25,000 cash prize provided by the NAC, a commissioned from Canadians for Canadians whose accomplishments work created by Canadian ceramic artist Paula Murray and have inspired and enriched the cultural life of our country. a commemorative medallion. Laureates of the Lifetime Artistic Achievement Award are All commemorative medallions are generously donated selected from the fields of broadcasting, classical music, by the Royal Canadian Mint. dance, film, popular music and theatre. Nominations for this Award and the Ramon John Hnatyshyn Award for The Awards also feature a unique Mentorship Program Voluntarism in the Performing Arts are open to the public designed to benefit a talented mid-career artist. and solicited from across the country. All nominations The Program brings together a past Lifetime Artistic are reviewed by juries of professionals in each discipline; Achievement Award recipient with a next-generation each jury submits a short list to the Board of Directors artist, helping them to develop their work, explore 2 of the Governor General’s Performing Arts Awards ideas and navigate career options. -

1975-76-Annual-Report.Pdf

19th Annual Report The Canada Council 1975-1976 Honorable Hugh Faulkner Secretary of State of Canada Ottawa, Canada Sir, I have the honor to transmit herewith the Annual Report of the Canada Council, for submission to Parliament, as required by section 23 of the Canada Council Act (5-6 Elizabeth 11, 1957, Chap. 3) for the fiscal year ending March 31, 1976. I am, Sir, Yours very truly, Gertrude M. Laing, O.C ., Chairman June 1,1976 The Canada Council is a corporation created by an Act of This report is produced and distributed by Parliament in 1957 "to foster and promote the study and Information Services, enjoyment of, and the production of works in, the arts, The Canada Council, humanities and the social sciences." It offers a broad 151 Sparks Street, range of grants and provides certain services to individuals Ottawa, Ontario and organizations in these and related fields. It is also re- sponsible for maintaining the Canadian Commission for Postal address: Unesco. Box 1047, Ottawa, Ontario K1 P 5V8 The Council sets its own policies and makes its own deci- Telephone: sions within the terms of the Canada Council Act. It re- (613) 237-3400 ports to Parliament through the Secretary of State and appears before the Standing Committee on Broadcasting, Films and Assistance to the Arts. The Canada Council itself consists of a Chairman, a Vice- Chairman, and 19 other members, all of whom are ap- pointed by the Government of Canada. They meet four or five times a year, usually in Ottawa where the Council of- fices are located.