Tanzanite: Commodity Fiction Or Commodity Nightmare? Katherine C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Total Lot Value = $8,189.80 LOT #128 Location Id Lot # Item Id Sku Image Store Price Model Store Quantity Classification Total Value

Total Lot Value = $8,189.80 LOT #128 location_id Lot # item_id sku Image store_price model store_quantity classification Total Value A07-S05-D001 128 182363 TICB-1001 $13.95 16G 5/16" Internally Threaded Implant Grade Titanium Curved Barbell 8 Curved Barbell $111.60 A07-S05-D003 128 186942 NR-1316 $8.95 Purple 2mm Bezel-Set Synthetic Opal Rose Gold-Tone Steel Nose Ring Twist 1 Nose Ring $8.95 A07-S05-D005 128 65492 A208 $11.99 Celtic Swirl Reverse Belly Button Ring 4 Belly Ring Sale $47.96 A07-S05-D006 128 104247 PLG-1345-14 $10.95 9/16" Pink Heart-Shaped Cut Out Flexible Silicone Tunnel Plugs Pair 4 Plugs $43.80 A07-S05-D007 128 65494 D103 $5.95 16G 3/8 - Anodized Rainbow Titanium-Plated Captive Bead Ring 3 Captive Ring , Daith $17.85 A07-S05-D008 128 65496 D103b $5.95 Rainbow Titanium-Plated Captive Bead Ring - 14G 1/2 1 Captive Ring $5.95 A07-S05-D010 128 65499 D103d $4.99 16G 5/8 - Rainbow Anodized Steel Captive Bead Ring 51 Captive Ring $254.49 A07-S05-D011 128 87697 BR-1429 $11.99 Pink CZ Crown & Flower Dangle Belly Button Navel Ring 2 Belly Ring Sale $23.98 A07-S05-D012 128 64066 BR-1496 $11.99 Purple CZ Crown & Flower Dangle Belly Button Navel Ring 4 Belly Ring Sale $47.96 A07-S05-D013 128 65502 D111 $5.99 Spiky -Ball Twister - Body Jewelry 14 Gauge 43 Twister Barbell Sale $257.57 A07-S05-D014 128 104271 PLG-1345-16 $10.95 5/8" - Pink Heart-Shaped Cut Out Flexible Silicone Tunnel Plugs - Pair 2 Plugs $21.90 A07-S05-D015 128 104185 PLG-1345-4 $8.95 6G - Pink Heart-Shaped Cut Out Flexible Silicone Tunnel Plugs - Pair 2 Plugs $17.90 -

Distinctive Designs

Distinctive Designs Brides Ring in an Era of Self-Expression by Stacey Marcus Diamond rings have been sporting the hands of newly can elevate a traditional setting to an entirely new level. While engaged women since ancient times. In the mid 1940s, diamonds are always in vogue for engagement rings, millen- DeBeers revived the ritual with its famous “Diamonds Are nials are also opting for nontraditional stones, such as color- Forever” campaign. Today’s brides are blazing new trails by changing alexandrite, beautiful tanzanite, black opal, and even selecting nontraditional wedding rings that express their aquamarine. We are in an age when anything goes, and brides individual style. are embracing the idea of individuality and self-expression!” True Colors says Jordan Fine, CEO of JFINE. “Brides today want to be unique and they don’t mind taking Kathryn Money, vice president of strategy and merchandising chances with colors, settings, and stones. When it comes to at Brilliant Earth agrees: “Customers are seeking products that choosing an engagement ring, natural pink, blue, and even express their individuality and are increasingly drawn towards green diamonds are trending. These precious and rare dia- uniqueness. They want a ring that isn’t like everyone else’s, monds originate from only a few mines in the world, and they which we’re seeing manifested in many different ways, such 34 Spring 2018 BRIDE&GROOM as choosing a distinctive ring setting, using colored gemstones in lieu of a diamond, using a fancy (non-round) diamond, or opting for rose gold.” Money adds that 16% of respondents in a recent survey they conducted favored a colored gemstone engagement ring over a diamond. -

MAGAZINE • LEAWOOD, KS SPECIAL EDITION 2016 ISSUE 3 Fine Jewelers Magazine

A TUFTS COMMUNICATIONS fine jewelry PUBLICATION MAZZARESE MAGAZINE • LEAWOOD, KS SPECIAL EDITION 2016 ISSUE 3 fine jewelers magazine Chopard: Racing Special The New Ferrari 488 GTB The Natural Flair of John Hardy Black Beauties Omega’s New 007 SPECIAL EDITION 2016 • ISSUE 3 MAZZARESE FINE JEWELERS MAGAZINE • SPECIAL EDITION 2016 welcome It is our belief that we have an indelible link with the past and a responsibility to the future. In representing the fourth generation of master jewelers and craftsmen, and even as the keepers of a second generation family business, we believe that the responsibility to continually evolve and develop lies with us. We endeavor to always stay ahead of the latest jewelry and watch trends and innovations. We stay true to our high standards and objectives set forth by those that came before us by delivering a jewelry experience like no other; through the utmost attention to service, knowledge and value. Every great story begins with a spark of inspiration. We are reminded day after day of our spark of inspiration: you, our esteemed customer. Your stories help drive our passion to pursue the finest quality pieces. It is a privilege that we are trusted to provide the perfect gift; one that stands the test of time and is passed along through generations. We find great joy in assisting the eager couple searching for the perfect engagement ring, as they embark on a lifetime of love, helping to select a quality timepiece, or sourcing a rare jewel to mark and celebrate a milestone. We are dedicated to creating an experience that nurtures relationships and allows those who visit our store to enter as customers, but leave as members of our family. -

Murostar-Katalog-2018-2019.Pdf

Material B2B Großhandel für Piercing- und Tattoo- B2B Wholesale for body piercing and Unsere Qualität ist Ihre Zufriedenheit Our quality is your satisfaction About Us studios, sowie Schmuck- und Juwelier- tattoo studios as well as jewelry stores vertriebe Oberste Priorität hat bei uns die reibungslose Abwicklung Our top priority is to provide a smooth transaction and fast Titan Produkte entsprechen dem Grad 23 (Ti6AL 4V Eli) und Titanium products correspond to titanium grade 23 (Ti6Al und schnelle Lieferung Ihrer Ware. Daher verlassen ca. 95 % delivery. Therefore, approximately 95% of all orders are sind generell hochglanzpoliert. Sterilisierbar. 4V Eli) and are generally high polished. For sterilization. aller Aufträge unser Lager noch am selben Tag. shipped out on the same day. Black Titan besteht grundsätzlich aus Titan Grad 23 (Ti6AL Black Titanium is composed of titanium grade 23 (Ti6Al 4V Unser dynamisches, kundenorientiertes Team sowie ausge- Our dynamic, customer-oriented team and excellent expe- 4V Eli) und ist zusätzlich mit einer PVD Titanium Beschich- Eli) and is additionally equipped with a PVD Black Titanium zeichnete Erfahrungswerte garantieren Ihnen einen hervor- rience guarantee excellent service and expert advice. tung geschwärzt. Sterilisierbar. Coating. For sterilization. ragenden Service und kompetente Beratung. Steel Schmuck besteht grundsätzlich aus Chirurgenstahl Steel jewelry is composed of 316L Surgical Steel and is also Sie bestellen schnell und unkompliziert online, telefo- Your order can be placed quickly and easily online, by 316L und ist ebenfalls hochglanzpoliert. Sterilisierbar. high polished. For sterilization. nisch, per Fax oder Email mittels unseres einfachen Ex- phone, fax or email using our simple Express Number press-Nummern-Systems ohne Angabe von Farb- oder Grö- System only without providing colors or sizes. -

Gem Wealth of Tanzania GEMS & GEMOLOGY Summer 1992 Fipe 1

By Dona M.Dirlarn, Elise B. Misiorowski, Rosemaiy Tozer, Karen B. Stark, and Allen M.Bassett The East African nation of Tanzania has he United Republic of Tanzania, the largest of the East great gem wealth. First known by Western- 1African countries, is composed of mainland Tanzania and ers for its diamonds, Tanzania emerged in the island of Zanzibar. 1t is regarded by many as the birthplace the 1960s as a producer of a great variety of of the earliest ancestors of Homo sapiens. To the gem indus- other gems such as tanzanite, ruby, fancy- try, however, Tanzania is one of the most promising fron- colored sapphire, garnet, and tourmaline; to date, more than 50 gem species and vari- tiers, with 50 gem species and varieties identified, to date, eties have been produced. As the 1990s from more than 200 occurrences. begin, De Beers has reinstated diamond "Modem" mining started in the gold fields of Tanzania in exploration in Tanzania, new gem materials the late 1890s (Ngunangwa, 19821, but modem diamond min- such as transparent green zoisite have ing did not start until 1925, and nearly all mining of colored appeared on the market, and there is stones has taken place since 1950. Even so, only a few of the increasing interest in Tanzania's lesser- gem materials identified have been exploited to any significant known gems such as scapolite, spinel, and extent: diamond, ruby, sapphire, purplish blue zoisite (tan- zircon. This overview describes the main zanite; figure l),and green grossular [tsavorite)and other gar- gems and gem resources of Tanzania, and nets. -

Guaranteed Shops Ocho Rios

DI_AD_PPI_110212.pdf 1 11/2/2012 12:48:01 PM GUARANTEED SHOPS OCHO RIOS SHOP SCAN SHOP&SCAN ACTIVATE YOUR SHOPPING GUARANTEE INTERNATIONAL LUXURY BRANDS Forevermark Diamonds • Tanzanite International Hearts On Fire Diamonds • Jewels & Time C M Y DESIGNER BRANDS CM MY Alex and Ani Jewelry • Jewels & Time CY Ammolite Jewelry by Korite • Tanzanite International CMY Crown of Light Diamonds • Tanzanite International K Ernst Benz Watches • Jewels & Time Fruitz Watches • Jewels & Time Gift Diamond Jewelry • Tanzanite International Glam Rock Watches • Jewels & Time John Hardy Jewelry • Jewels & Time Kabana Jewelry • Tanzanite International Mark Henry Alexandrite Jewelry • Jewels & Time Movado Watches • Tanzanite International Parazul Handbags & Accessories • Jewels & Time Philip Stein Watches • Jewels & Time Safi Kilima Tanzanite Jewelry• Tanzanite International AT A GLANCE IN CASE OF EMERGENCY PORT & SHOPPING Capital: Kingston Lannaman & Morris (Shipping) Ltd. CHANNEL Location: 90 miles south of Cuba Ocho Rios Cruise Ship Terminal Tune in to the Port Channel for the latest Taxi: Taxis are available P.O. Box 201 Ocho Rios updated port and shopping information. Currency: Jamaican dollar St. Ann Jamaica PORT SHOPPING BUYER’S GUARANTEE Consult your Freestyle Daily for Language: English, Sharon Snape The Port Shopping Program is operated by The PPI Group and the stores listed on this map and mentioned in the Port & Shopping Presentations have paid an advertising fee to promote shopping channel listing. opportunities ashore. These stores provide a 30-day guarantee after purchase to Norwegian Cruise Line’s guests. This guarantee is valid for repair or exchange. Buyer’s negligence and buyer’s English-based patois Tel: (876) 974-5681 / 974-2983 remorse are excluded from the guarantee. -

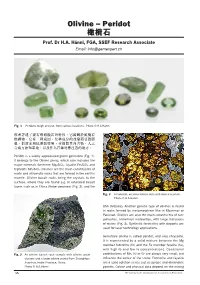

Olivine – Peridot 橄欖石 Prof

Olivine – Peridot 橄欖石 Prof. Dr H.A. Hänni, FGA, SSEF Research Associate Email: [email protected] Fig. 1 Peridots rough and cut, from various locations. Photo © H.A.Hänni 作者述了寶石級橄欖石的特性,它歸屬於橄欖石 類礦物,它有三種成因,化學成的改變而引致顏 色、折射率和比重的變異,並簡報其內含物、人工 合成方法和產地,以及作為首飾時應注意的地方。 Peridot is a widely appreciated green gemstone (Fig. 1). It belongs to the Olivine group, which also includes the major minerals forsterite Mg2SiO4, fayalite Fe2SiO4 and tephroite Mn2SiO4. Olivines are the main constituents of maic and ultramaic rocks that are formed in the earth’s mantle. Olivine-basalt rocks bring the crystals to the surface, where they are found e.g. in extended basalt layers such as in China (Hebei province) (Fig. 2), and the Fig. 3 A Pallasite, an iron-nickel matrix with olivine crystals. Photo © H.A.Hänni USA (Arizona). Another genetic type of olivines is found in rocks formed by metamorphism like in Myanmar or Pakistan. Olivines are also the main constituents of rare pallasites, nickel-iron meteorites, with large inclusions of olivine (Fig. 3). Synthetic forsterites with dopants are used for laser technology applications. Gemstone olivine is called peridot, and also chrysolite. It is represented by a solid mixture between the Mg member forsterite (fo) and the Fe member fayalite (fa), with high fo and low fa concentrations. Occasional Fig. 2 An olivine-basalt rock sample with olivine grain contributions of Mn, Ni or Cr are always very small, but clusters and a larger olivine crystal from Zhangjikou- inluence the colour of the stone. Forsterite and fayalite Xuanhua, Hebei Province, China. are a solid solution series just as pyrope and almandine Photo © H.A.Hänni garnets. -

Weight of Production of Emeralds, Rubies, Sapphires, and Tanzanite from 1995 Through 2005

Weight of Production of Emeralds, Rubies, Sapphires, and Tanzanite from 1995 Through 2005 By Thomas R. Yager, W. David Menzie, and Donald W. Olson Open-File Report 2008–1013 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2008 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested citation: Yager, T.R., Menzie, W.D., and Olson, D. W., 2008, Weight of production of emeralds, rubies, sapphires, and tanzanite from 1995 through 2005: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2008-1013, 9 p., available only online, http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2008/1013. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. ii Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................1 Emeralds.......................................................................................................................................2 -

October 2021 : CA Category Changes

October 2021 : CA Category Changes Change Type Count New 473 Retired 2143 Rename 169 Move 40 Move & Rename 49 Total 2874 Category Name Category ID Comments Actions Required + Antiques 20081 - Art 550 Fine Art Drawings 552 Art NFTs 262051 Fine Art Photographs 2211 Before 12 October: If you would like your All listings are being moved into [Other listings to be moved into an appropriate Folk Art & Indigenous Art 357 Art - 20158]. category, please use the applicable eBay recommended item specifics. Art Posters 28009 Fine Art Prints 360 Fine Art Sculptures 553 Mixed Media Art & Collage Art 554 Paintings 551 Textile Art & Fibre Art 156196 Other Art 20158 - Automotive 6000 + Cars & Trucks 6001 + Motorcycles 6024 + Other Vehicles & Trailers 6038 + Boats 26429 + Powersports 66466 - Parts & Accessories 6028 + ATV, Side-by-Side & UTV Parts & Accessories 43962 + Apparel, Protective Gear & Merchandise 6747 + Aviation Parts & Accessories 26435 + Boat Parts 26443 - In-Car Technology, GPS & Security 38635 + In-Car Entertainment 171101 + Electronic Accessories 169423 - Dash Cams, Alarms & Security 169321 Anti-Sleep Systems 185021 Anti-Theft Car Alarms 75329 Car Immobilizers 173712 Car Keys, Fobs & Remotes 53908 CA_Category_Changes_Oct2021 - Page 1 of 284 Category Name Category ID Comments Actions Required Car Tracking Systems 173713 Dash Cams 174121 Key Blanks 40016 Moved from [Ignition Systems-33687] Remote Entry System Kits 184651 Remote Start System Kits 184652 Other Car Dash Cams, Alarms & Security Devices 169335 + GPS & Sat Nav Devices 139835 + Terminals & Wiring 179672 + DIY for Speakers & Subwoofers 138854 Radios for Parts 14262 Vintage Radios 96370 Other In-Car Technology 185012 - Car & Truck Parts & Accessories 6030 Renamed from [Car & Truck Parts] Before 12 October: If you would like your All listings are being moved into [Other listings to be moved into an appropriate Accessories 179413 Car & Truck Parts & Accessories - 9886]. -

Gemstone Identification Using Raman Spectroscopy

RM APPLICATION NOTE 01-03 Gemstone Identification Using Raman Spectroscopy In recent years, the gemstone market has been flooded with stones of questionable origin. Frequently, even thorough analysis by a qualified jeweler cannot unequivocally reveal whether a gemstone is genuine or fake. In the worst case, even sophisticated analytical methods struggle to differentiate modified diamonds, causing Figure 1. Diamonds of varying color. considerable concern to the international gemstone trade. Raman micro-spectroscopy is an ideal method for the examination of marketable Laboratory grown crystals of ruby, sapphire, diamond, gemstones. The lack of sample preparation and the emerald, and star sapphire are real semiprecious non-destructive nature of Raman analysis make it stones. They just weren’t grown in the earth. So what ideal for the analysis of even high-value gems. is the answer: Real or Fake? This argument can be Plus, the micro-Raman study of a stone provides a discussed with all sides being technically correct, but it unique record for identification purposes. We will is not the most important information. From a lapidary discuss the variety of Raman spectra that can be or jeweler’s point of view, the most important topic is obtained from different families of gemstones, proper disclosure. Does the buyer know up front that comparing and contrasting spectra from genuine the stone he is purchasing has been ‘helped along’ by and artificial materials. the human touch? Gems are often examined by trained personnel Introduction using optical microscopy and other methods. In some well-studied cases like diamond, these techniques will Gemstones and semi-precious stones have been usually suffice. -

TRIUMPH of COLOUR Fancy Colour Rough and Polished Diamonds Win the Market Editorial Note

IN-HOUSE PUBLICATION OF THE LARGEST DIAMOND MINING COMPANY SEPTEMBER 2018 CARATS ON THE What is the difference between customers’ profiles in China and the USA? 500ALROSA social responsibility projects Head of ALROSA SERGEY MATTER OF IVANOV: TECHNIQUE “We change New player in response to new in the diamond challenges” detection market TRIUMPH OF COLOUR Fancy colour rough and polished diamonds win the market Editorial note STEPAN PISAKHOV, A XX CENTURY WRITER AND ARTIST FROM THE ARKHANGELSK REGION, which is world-famous for coloured diamonds minable there, in his fairytale “Frozen songs” (Morozheny pesni) tells how semiprecious stones came out of songs. The local people pronounced words in the freezing cold; the words remained frozen till thawing weather, and when it got warmer they thawed and sang again. “We have fences shored with strong words, and old men and women lean on warmly said words.” And delightful laces shining like diamonds were resulted from songs of maidens and women. Houses were SMART HELPER FOR PICKING decorated with these diamond laces; and venturers brought the frozen diamond songs to other countries. NATURAL DIAMONDS JEWELRY This issue of the magazine is dedicated to the way in which PORTABLE DIAMOND DETECTOR the gems of unique hues appear by quaint plan of nature, INTELLIGENT AND USERFRIENDLY about special aspects and possibilities of fancy colour diamonds market, and ALROSA colour gems mining and faceting. We also tell about selling of the most valuable diamond of the Company, about new development in diamond origin detection, about the • polished natural diamonds; most outstanding social responsibility projects of ALROSA. -

JDI Brazil and Tanzania Report Fall 2019

1 2 Executive Summary This report presents the research findings of the fifth team of graduate students from the School of International Service at American University in fulfillment of their capstone requirement. In accordance with the statement of work, this report analyzes the impact on human security of amethyst and citrine in Brazil and tanzanite in Tanzania. The research team identified the human security risks per five United Nations (UN) Human Security Indicators: governance, economy, environment, health, and human rights. There is not a universal tool that analyzes the global jewelry industries’ impact on a host country. The jewelry industry can benefit host counties and local communities by creating jobs, increasing local revenue, and providing social services. However, these industries also can harm countries as mining can irreparably damage the local environment, cause chronic health problems for miners and residents of mining communities, and potentially present challenges to human rights. The Jewelry Development Impact Index (JDII) is a research project by American University Graduate Students in coordination with the U.S. Department of State, Office of Threat Finance Countermeasures, and the University of Delaware, Minerals, Materials, and Society Program. This report, in combination with the four previous reports, contributes to a uniform measurement tool to assess the impact of the jewelry industry on local human security and development. The research team used academic journals, business sector and NGO reports, news articles, and interviews with key stakeholders to score each country on a seven-point Likert. On this scale, a higher score (on a scale of one to seven) indicates that the industry does not present a significant human security risk.