To Download the PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biographies of Meeting Participants

As of 12/6/09 The Committee of 100 Leadership Delegation (December 7-14, 2009) Biographies of Meeting Participants December 7, 2009 (Beijing) 6:30PM dinner with C-100 Members John Chen, Chairman of Committee of 100 Mr. Chen is Chairman of the Committee of 100. He has served as Chairman, Chief Executive Officer, and President of Sybase, Inc. since 1998. Forbes magazine named Chen one of the Top 25 Notable Chinese Americans in Business. Chen is actively involved in international relations. In 2005, President George W. Bush appointed him to serve on the President’s Export Council. In 2006, he was appointed co-chair of the Secure Borders and Open Doors Advisory Committee. He serves on the boards of directors for the Walt Disney Company and Wells Fargo & Co. Kai-Fu Lee, Chairman and CEO of Innovation Works Dr. Lee is Chairman and CEO of Innovation Works. From 2005-2009, he was Vice President of Google, Inc. and President of Google Greater China. Before joining Google, he was Corporate Vice President for Microsoft and was founder of Microsoft Research Asia. From 1996 to 1998, Lee was the President of Cosmo Software, a subsidiary of Silicon Graphics (SGI). Lee also spent six years at Apple. From 1988 to 1990, he was an Assistant Professor at Carnegie Mellon University. Roger Wang, Chairman and CEO of Golden Eagle International Group Mr. Wang is the Chairman and CEO of Golden Eagle International Group. Founded in 1992 with headquarters in the historic former Chinese capital of Nanjing, Golden Eagle began as a real estate development company in a newly opened China, focusing primarily on the province of Jiangsu. -

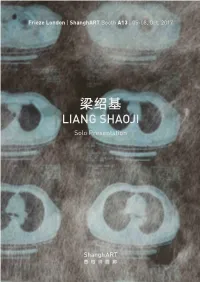

梁绍基 LIANG SHAOJI Solo Presentation 梁绍基 Liang Shaoji B

Frieze London | ShanghART Booth A13 | 05-08, Oct. 2017 梁绍基 LIANG SHAOJI Solo Presentation 梁绍基 Liang Shaoji b. 1945, now lives and works in Tiantai, Zhejiang Liang Shaoji (72-year-old) is one of the most unique and singular figures in the contemporary art scene in China. For 28 years, he has been working with his unusual partners - silkworms. Dubbed as a hermit residing in Tiantai (four-hour driving distance from Shanghai), Liang Shaoji patiently and purely devotes to art by his idiosyncratic creations imbued with ecological aesthetics. He discovers some kind of critical point where science and nature, biology and bio-ecology, weaving and sculpture, installation and performance might meet. His Nature Series sees the life process of silkworms as creation medium, the interaction in natural world as his artistic language, time and life as the essential idea. His works are fulfilled with a sense of meditation, philosophy and poetry while illustrating the inherent beauty of silk. Liang Shaoji's works have been internationally presented at: Cloud Above Cloud, Museum of China Academy of Art, Hangzhou (2016); What About the Art? Contemporary Art from China, Al Riwaq, Doha (2016); Liang Shaoji: Back to Origin, ShanghART Gallery, Shanghai (2014); Liang Shaoji: Questioning Heaven, Gao Magee Art Gallery, Madrid (2012); Art of Change, Hayward Gallery, London (2012); Liang Shaoji, Prince Claus Fund, Amsterdam (2009); Liang Shaoji: An Infinitely Fine Line, Zendai MOMA, Shanghai (2009); Liang Shaoji: Cloud, ShanghART H-Space, Shanghai (2007); The 5th Biennale d'Art Contemporain de Lyon, Lyon (2005); The 6th International Istanbul Biennial, Istanbul, Turkey (1999); The 48th Venice Biennale, Venice (1999); China/Avant-Garde Art Exhibition, National Art Museum of China, Beijing (1989) etc. -

(Chen Qiulin), 25F a Cheng, 94F a Xian, 276 a Zhen, 142F Abso

Index Note: “f ” with a page number indicates a figure. Anti–Spiritual Pollution Campaign, 81, 101, 102, 132, 271 Apartment (gongyu), 270 “......” (Chen Qiulin), 25f Apartment art, 7–10, 18, 269–271, 284, 305, 358 ending of, 276, 308 A Cheng, 94f internationalization of, 308 A Xian, 276 legacy of the guannian artists in, 29 A Zhen, 142f named by Gao Minglu, 7, 269–270 Absolute Principle (Shu Qun), 171, 172f, 197 in 1980s, 4–5, 271, 273 Absolution Series (Lei Hong), 349f privacy and, 7, 276, 308 Abstract art (chouxiang yishu), 10, 20–21, 81, 271, 311 space of, 305 Abstract expressionism, 22 temporary nature of, 305 “Academic Exchange Exhibition for Nationwide Young women’s art and, 24 Artists,” 145, 146f Apolitical art, 10, 66, 79–81, 90 Academicism, 78–84, 122, 202. See also New academicism Appearance of Cross Series (Ding Yi), 317f Academic realism, 54, 66–67 Apple and thinker metaphor, 175–176, 178, 180–182 Academic socialist realism, 54, 55 April Fifth Tian’anmen Demonstration (Li Xiaobin), 76f Adagio in the Opening of Second Movement, Symphony No. 5 April Photo Society, 75–76 (Wang Qiang), 108f exhibition, 74f, 75 Adam and Eve (Meng Luding), 28 Architectural models, 20 Aestheticism, 2, 6, 10–11, 37, 42, 80, 122, 200 Architectural preservation, 21 opposition to, 202, 204 Architectural sites, ritualized space in, 11–12, 14 Aesthetic principles, Chinese, 311 Art and Language group, 199 Aesthetic theory, traditional, 201–202 Art education system, 78–79, 85, 102, 105, 380n24 After Calamity (Yang Yushu), 91f Art field (yishuchang), 125 Agree -

Performance Art

(hard cover) PERFORMANCE ART: MOTIVATIONS AND DIRECTIONS by Lee Wen Master of Arts Fine Arts 2006 LASALLE-SIA COLLEGE OF THE ARTS (blank page) PERFORMANCE ART: MOTIVATIONS AND DIRECTIONS by Lee Wen Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Master of Arts (Fine Arts) LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts Faculty of Fine Arts Singapore May, 2006 ii Accepted by the Faculty of Fine Arts, LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree Master of Arts (Fine Arts). Vincent Leow Studio Supervisor Adeline Kueh Thesis Supervisor I certify that the thesis being submitted for examination is my own account of my own research, which has been conducted ethically. The data and the results presented are the genuine data and results actually obtained by me during the conduct of the research. Where I have drawn on the work, ideas and results of others this has been appropriately acknowledged in the thesis. The greater portion of the work described in the thesis has been undertaken subsequently to my registration for the degree for which I am submitting this document. Lee Wen In submitting this thesis to LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations and policies of the college. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the work may be made available and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. This work is also subject to the college policy on intellectual property. -

September/October 2016 Volume 15, Number 5 Inside

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2016 VOLUME 15, NUMBER 5 INSI DE Chengdu Performance Art, 2012–2016 Interview with Raqs Media Collective on the 2016 Shanghai Biennale Artist Features: Cui Xiuwen, Qu Fengguo, Ying Yefu, Zhou Yilun Buried Alive: Chapter 1 US$12.00 NT$350.00 PRINTED IN TAIWAN 6 VOLUME 15, NUMBER 5, SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2016 C ONT ENT S 23 2 Editor’s Note 4 Contributors 6 Chengdu Performance Art, 2012–2016 Sophia Kidd 23 Qu Fengguo: Temporal Configurations Julie Chun 36 36 Cui Xiuwen Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky 48 Propositioning the World: Raqs Media Collective and the Shanghai Biennale Maya Kóvskaya 59 The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly Danielle Shang 48 67 Art Labor and Ying Yefu: Between the Amateur and the Professional Jacob August Dreyer 72 Buried Alive: Chapter 1 (to be continued) Lu Huanzhi 91 Chinese Name Index 59 Cover: Zhang Yu, One Man's Walden Pond with Tire, 2014, 67 performance, one day, Lijiang. Courtesy of the artist. We thank JNBY Art Projects, Chen Ping, David Chau, Kevin Daniels, Qiqi Hong, Sabrina Xu, David Yue, Andy Sylvester, Farid Rohani, Ernest Lang, D3E Art Limited, Stephanie Holmquist, and Mark Allison for their generous contribution to the publication and distribution of Yishu. 1 Editor’s Note YISHU: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art PRESIDENT Katy Hsiu-chih Chien LEGAL COUNSEL Infoshare Tech Law Office, Mann C. C. Liu Performance art has a strong legacy in FOUNDING EDITOR Ken Lum southwest China, particularly in the city EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Keith Wallace MANAGING EDITOR Zheng Shengtian of Chengdu. Sophia Kidd, who previously EDITORS Julie Grundvig contributed two texts on performance art in this Kate Steinmann Chunyee Li region (Yishu 44, Yishu 55), updates us on an EDITORS (CHINESE VERSION) Yu Hsiao Hwei Chen Ping art medium that has shifted emphasis over the Guo Yanlong years but continues to maintain its presence CIRCULATION MANAGER Larisa Broyde WEB SITE EDITOR Chunyee Li and has been welcomed by a new generation ADVERTISING Sen Wong of artists. -

Patrick J. Hurley's Attempt to Unify China, 1944-1945

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 66-11 791 SMITH, Robert Thomas, 1938- ALONE IN CHINA; PATRICK J. HURLEY'S ATTEMPT TO UNIFY CHINA, 1944-1945. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1966 History, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan C opyright by ROBERT THOMAS SMITH 1966 THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHCMA GRADUATE COLLEGE ALONE IN CHINA: PATRICK J . HURLEY'S ATTEMPT TO UNIFY CHINA, 1944-1945 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY ROBERT THCÎ-1AS SMITH Norman, Oklahoma 1966 ALŒE IN CHINA; PATRICK J . HURLEY'S ATTEMPT TO UNIFY CHINA, 1944-1945 APPP>Î BY 'c- l <• ,L? T\ . , A. c^-Ja ^v^ c c \ (LjJ LSSERTATION COMMITTEE ACKNOWLEDGMENT 1 wish to acknowledge the aid and assistance given by my major professor, Dr, Gilbert 0, Fite, Research Professor of History, I desire also to thank Professor Donald J, Berthrong who acted as co-director of my dissertation before circumstances made it impossible for him to continue in that capacity. To Professors Percy W, Buchanan, J, Carroll Moody, John W, Wood, and Russell D, Buhite, \^o read the manuscript and vdio each offered learned and constructive criticism , I shall always be grateful, 1 must also thank the staff of the Manuscripts Divi sion of the Bizzell Library \diose expert assistance greatly simplified the task of finding my way through the Patrick J, Hurley collection. Special thanks are due my wife vdio volun teered to type the manuscript and offered aid in all ways imaginable, and to my parents \dio must have wondered if I would ever find a job. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION The wuxia film is the oldest genre in the Chinese cinema that has remained popular to the present day. Yet despite its longevity, its history has barely been told until fairly recently, as if there was some force denying that it ever existed. Indeed, the genre was as good as non-existent in China, its country of birth, for some fifty years, being proscribed over that time, while in Hong Kong, where it flowered, it was gen- erally derided by critics and largely neglected by film historians. In recent years, it has garnered a following not only among fans but serious scholars. David Bordwell, Zhang Zhen, David Desser and Leon Hunt have treated the wuxia film with the crit- ical respect that it deserves, addressing it in the contexts of larger studies of Hong Kong cinema (Bordwell), the Chinese cinema (Zhang), or the generic martial arts action film and the genre known as kung fu (Desser and Hunt).1 In China, Chen Mo and Jia Leilei have published specific histories, their books sharing the same title, ‘A History of the Chinese Wuxia Film’ , both issued in 2005.2 This book also offers a specific history of the wuxia film, the first in the English language to do so. It covers the evolution and expansion of the genre from its beginnings in the early Chinese cinema based in Shanghai to its transposition to the film industries in Hong Kong and Taiwan and its eventual shift back to the Mainland in its present phase of development. Subject and Terminology Before beginning this history, it is necessary first to settle the question ofterminology , in the process of which, the characteristics of the genre will also be outlined. -

Behind the Thriving Scene of the Chinese Art Market -- a Research

Behind the thriving scene of the Chinese art market -- A research into major market trends at Chinese art market, 2006- 2011 Lifan Gong Student Nr. 360193 13 July 2012 [email protected] Supervisor: Dr. F.R.R.Vermeylen Second reader: Dr. Marilena Vecco Master Thesis Cultural economics & Cultural entrepreneurship Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication Erasmus University Rotterdam 1 Abstract Since 2006, the Chinese art market has amazed the world with an unprecedented growth rate. Due to its recent emergence and disparity from the Western art market, it remains an indispensable yet unfamiliar subject for the art world. This study penetrates through the thriving scene of the Chinese art market, fills part of the gap by presenting an in-depth analysis of its market structure, and depicts the route of development during 2006-2011, the booming period of the Chinese art market. As one of the most important and largest emerging art markets, what are the key trends in the Chinese art market from 2006 to 2011? This question serves as the main research question that guides throughout the research. To answer this question, research at three levels is unfolded, with regards to the functioning of the Chinese art market, the geographical shift from west to east, and the market performance of contemporary Chinese art. As the most vibrant art category, Contemporary Chinese art is chosen as the focal art sector in the empirical part since its transaction cover both the Western and Eastern art market and it really took off at secondary art market since 2005, in line with the booming period of the Chinese art market. -

The Transcendence of the Arts in China and Beyond (Lissabon, 4-5 Apr 13)

The transcendence of the Arts in China and Beyond (Lissabon, 4-5 Apr 13) Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Lisbon, PORTUGAL, Apr 4–05, 2013 Deadline: Jul 31, 2012 Rui Oliveira Lopes, Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Lisbon 'Face to Face. The transcendence of the Arts in China and Beyond' Organizers: Fernando António Baptista Pereira Associated Professor, Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Lisbon Rui Oliveira Lopes Postdoctoral Researcher, Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Lisbon Conference Language English / Portuguese Conference Description Face to Face. The Transcendence of the Arts in China and Beyond is a conference that will bring a wide range of new perspectives on the artistic styles changes of Chinese Arts, resulting from the artistic exchange and mutual interactions with the arts, styles and techniques of other cultures in China itself and beyond its cultural frontiers. Given to the long artistic traditions and the multicultural sediment of Chinese arts it is critical to present a selection of comparative perspectives on the legacy of other artistic traditions in the arts of China, from the Bronze Age to Modern-day, crossing through ceramics, metalwork, paint- ing, sculpture, carving, prints, textiles, drama (theatre, opera, shadow puppetry and cinema), and performing arts (music and dance). Our goals for the conference are to raise awareness of the artistic exchange and mutual influ- ences between the Han Chinese arts and the arts from different cultural backgrounds in China itself, as well as beyond its geographical and cultural boundaries. We also aim to go through the issues on the construction of artistic identity and the balance between permeability and hege- mony, tradition and innovation, convenience and misinterpretation. -

Art As Communication: Y the Impact of Art As a Catalyst for Social Change Cm

capa e contra capa.pdf 1 03/06/2019 10:57:34 POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE OF LISBON . PORTUGAL C M ART AS COMMUNICATION: Y THE IMPACT OF ART AS A CATALYST FOR SOCIAL CHANGE CM MY CY CMY K Fifteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society Against the Grain: Arts and the Crisis of Democracy NUI Galway Galway, Ireland 24–26 June 2020 Call for Papers We invite proposals for paper presentations, workshops/interactive sessions, posters/exhibits, colloquia, creative practice showcases, virtual posters, or virtual lightning talks. Returning Member Registration We are pleased to oer a Returning Member Registration Discount to delegates who have attended The Arts in Society Conference in the past. Returning research network members receive a discount o the full conference registration rate. ArtsInSociety.com/2020-Conference Conference Partner Fourteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society “Art as Communication: The Impact of Art as a Catalyst for Social Change” 19–21 June 2019 | Polytechnic Institute of Lisbon | Lisbon, Portugal www.artsinsociety.com www.facebook.com/ArtsInSociety @artsinsociety | #ICAIS19 Fourteenth International Conference on the Arts in Society www.artsinsociety.com First published in 2019 in Champaign, Illinois, USA by Common Ground Research Networks, NFP www.cgnetworks.org © 2019 Common Ground Research Networks All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the applicable copyright legislation, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. For permissions and other inquiries, please visit the CGScholar Knowledge Base (https://cgscholar.com/cg_support/en). -

William Gropper's

US $25 The Global Journal of Prints and Ideas March – April 2014 Volume 3, Number 6 Artists Against Racism and the War, 1968 • Blacklisted: William Gropper • AIDS Activism and the Geldzahler Portfolio Zarina: Paper and Partition • Social Paper • Hieronymus Cock • Prix de Print • Directory 2014 • ≤100 • News New lithographs by Charles Arnoldi Jesse (2013). Five-color lithograph, 13 ¾ x 12 inches, edition of 20. see more new lithographs by Arnoldi at tamarind.unm.edu March – April 2014 In This Issue Volume 3, Number 6 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Fierce Barbarians Associate Publisher Miguel de Baca 4 Julie Bernatz The Geldzahler Portfoio as AIDS Activism Managing Editor John Murphy 10 Dana Johnson Blacklisted: William Gropper’s Capriccios Makeda Best 15 News Editor Twenty-Five Artists Against Racism Isabella Kendrick and the War, 1968 Manuscript Editor Prudence Crowther Shaurya Kumar 20 Zarina: Paper and Partition Online Columnist Jessica Cochran & Melissa Potter 25 Sarah Kirk Hanley Papermaking and Social Action Design Director Prix de Print, No. 4 26 Skip Langer Richard H. Axsom Annu Vertanen: Breathing Touch Editorial Associate Michael Ferut Treasures from the Vault 28 Rowan Bain Ester Hernandez, Sun Mad Reviews Britany Salsbury 30 Programs for the Théâtre de l’Oeuvre Kate McCrickard 33 Hieronymus Cock Aux Quatre Vents Alexandra Onuf 36 Hieronymus Cock: The Renaissance Reconceived Jill Bugajski 40 The Art of Influence: Asian Propaganda Sarah Andress 42 Nicola López: Big Eye Susan Tallman 43 Jane Hammond: Snapshot Odyssey On the Cover: Annu Vertanen, detail of Breathing Touch (2012–13), woodcut on Maru Rojas 44 multiple sheets of machine-made Kozo papers, Peter Blake: Found Art: Eggs Unique image. -

JUNE 2005 SUMMER ISSUE Dialogue with Hans Ulrich Obrist

JUNE 2005 SUMMER ISSUE INSIDE Dialogue with Hans Ulrich Obrist and Huo Hanru on the 2nd Guangzhou Triennial On Curating Cruel/Loving Bodies The Yellow Box: Thoughts on Art before the Age of Exhibitions Interviews with Michael Lin and Hu Jieming From Iconic to Symbolic: Ah Xian’s Semiotic Interface Between China and the West Place and Displace: Three Generations of Taiwanese Art US$12.00 NT$350.00 US$10.00 NT$350.00 Editor’s Note Contributors : Opening remarks Richard Vinograd p. 7 Re-Placing Contemporary Chinese Art Richard Vinograd Remarks Michael Sullivan : Prodigal Sons: Chinese Artists Return to the Homeland Melissa Chiu Between Truth and Fiction: Notes on Fakes, Copies and Authenticity in Contemporary Chinese Art Pauline J. Yao Ink Painting in the Contemporary Chinese Art World Shen Kuiyi Remarks p. 12 Richard Vinograd : Reflections on the First Chinese Art Seminar/Workshop, San Diego 1991 Zheng Shengtian Between the Worlds: Chinese Art at Biennials Since 1993 John Clark Between Scylla and Charybdis: The New Context of Chinese Contemporary Art and Its Creation since 2000 Pi Li Remarks: “Whose Stage Is It, Anyway?” Reflections on the Correlation of “Beauty” and International Exhibition Practices of Chinese Contemporary Art p. 83 Francesca Dal Lago : How Western People Support/Influence Contemporary Chinese Art Zhou Tiehai The Positioning of Chinese Contemporary Artworks in the International Art Market Uli Sigg Chinese Contemporary Art: At the Margin of the American Mainstream Jane Debevoise Remarks Britta Erickson p. 93 Artist Project: Zhou Tiehai WILL On the Edge Visiting Artists Program Britta Erickson On the Spot: The Stanford Visiting Artists Program Pauline J.