Designing a Mixed Member Proportional System for Consideration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Generalization of the Minisum and Minimax Voting Methods

A Generalization of the Minisum and Minimax Voting Methods Shankar N. Sivarajan Undergraduate, Department of Physics Indian Institute of Science Bangalore 560 012, India [email protected] Faculty Advisor: Prof. Y. Narahari Deparment of Computer Science and Automation Revised Version: December 4, 2017 Abstract In this paper, we propose a family of approval voting-schemes for electing committees based on the preferences of voters. In our schemes, we calcu- late the vector of distances of the possible committees from each of the ballots and, for a given p-norm, choose the one that minimizes the magni- tude of the distance vector under that norm. The minisum and minimax methods suggested by previous authors and analyzed extensively in the literature naturally appear as special cases corresponding to p = 1 and p = 1; respectively. Supported by examples, we suggest that using a small value of p; such as 2 or 3, provides a good compromise between the minisum and minimax voting methods with regard to the weightage given to approvals and disapprovals. For large but finite p; our method reduces to finding the committee that covers the maximum number of voters, and this is far superior to the minimax method which is prone to ties. We also discuss extensions of our methods to ternary voting. 1 Introduction In this paper, we consider the problem of selecting a committee of k members out of n candidates based on preferences expressed by m voters. The most common way of conducting this election is to allow each voter to select his favorite candidate and vote for him/her, and we select the k candidates with the most number of votes. -

Are Condorcet and Minimax Voting Systems the Best?1

1 Are Condorcet and Minimax Voting Systems the Best?1 Richard B. Darlington Cornell University Abstract For decades, the minimax voting system was well known to experts on voting systems, but was not widely considered to be one of the best systems. But in recent years, two important experts, Nicolaus Tideman and Andrew Myers, have both recognized minimax as one of the best systems. I agree with that. This paper presents my own reasons for preferring minimax. The paper explicitly discusses about 20 systems. Comments invited. [email protected] Copyright Richard B. Darlington May be distributed free for non-commercial purposes Keywords Voting system Condorcet Minimax 1. Many thanks to Nicolaus Tideman, Andrew Myers, Sharon Weinberg, Eduardo Marchena, my wife Betsy Darlington, and my daughter Lois Darlington, all of whom contributed many valuable suggestions. 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction and summary 3 2. The variety of voting systems 4 3. Some electoral criteria violated by minimax’s competitors 6 Monotonicity 7 Strategic voting 7 Completeness 7 Simplicity 8 Ease of voting 8 Resistance to vote-splitting and spoiling 8 Straddling 8 Condorcet consistency (CC) 8 4. Dismissing eight criteria violated by minimax 9 4.1 The absolute loser, Condorcet loser, and preference inversion criteria 9 4.2 Three anti-manipulation criteria 10 4.3 SCC/IIA 11 4.4 Multiple districts 12 5. Simulation studies on voting systems 13 5.1. Why our computer simulations use spatial models of voter behavior 13 5.2 Four computer simulations 15 5.2.1 Features and purposes of the studies 15 5.2.2 Further description of the studies 16 5.2.3 Results and discussion 18 6. -

Candidate Ranking Strategies Under Closed List Proportional Representation

The Best at the Top? Candidate Ranking Strategies Under Closed List Proportional Representation Benoit S Y Crutzen Hideo Konishi Erasmus School of Economics Boston College Nicolas Sahuguet HEC Montreal April 21, 2021 Abstract Under closed-list proportional representation, a party’selectoral list determines the order in which legislative seats are allocated to candidates. When candidates differ in their ability, parties face a trade-off between competence and incentives. Ranking candidates in decreasing order of competence ensures that elected politicians are most competent. Yet, party list create incentives for candidates that may push parties not to rank candidates in decreasing competence order. We examine this trade-off in a game- theoretical model in which parties rank their candidate on a list, candidates choose their campaign effort, and the election is a team contest for multiple prizes. We show that the trade-off between competence and incentives depends on candidates’objective and the electoral environment. In particular, parties rank candidates in decreasing order of competence if candidates value enough post-electoral high offi ces or media coverage focuses on candidates at the top of the list. 1 1 Introduction Competent politicians are key for government and democracy to function well. In most democracies, political parties select the candidates who can run for offi ce. Parties’decision on which candidates to let run under their banner is therefore of fundamental importance. When they select candidates, parties have to worry not only about the competence of candidates but also about incentives, about their candidates’motivation to engage with voters and work hard for their party’selectoral success. -

Single-Winner Voting Method Comparison Chart

Single-winner Voting Method Comparison Chart This chart compares the most widely discussed voting methods for electing a single winner (and thus does not deal with multi-seat or proportional representation methods). There are countless possible evaluation criteria. The Criteria at the top of the list are those we believe are most important to U.S. voters. Plurality Two- Instant Approval4 Range5 Condorcet Borda (FPTP)1 Round Runoff methods6 Count7 Runoff2 (IRV)3 resistance to low9 medium high11 medium12 medium high14 low15 spoilers8 10 13 later-no-harm yes17 yes18 yes19 no20 no21 no22 no23 criterion16 resistance to low25 high26 high27 low28 low29 high30 low31 strategic voting24 majority-favorite yes33 yes34 yes35 no36 no37 yes38 no39 criterion32 mutual-majority no41 no42 yes43 no44 no45 yes/no 46 no47 criterion40 prospects for high49 high50 high51 medium52 low53 low54 low55 U.S. adoption48 Condorcet-loser no57 yes58 yes59 no60 no61 yes/no 62 yes63 criterion56 Condorcet- no65 no66 no67 no68 no69 yes70 no71 winner criterion64 independence of no73 no74 yes75 yes/no 76 yes/no 77 yes/no 78 no79 clones criterion72 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 monotonicity yes no no yes yes yes/no yes criterion80 prepared by FairVote: The Center for voting and Democracy (April 2009). References Austen-Smith, David, and Jeffrey Banks (1991). “Monotonicity in Electoral Systems”. American Political Science Review, Vol. 85, No. 2 (June): 531-537. Brewer, Albert P. (1993). “First- and Secon-Choice Votes in Alabama”. The Alabama Review, A Quarterly Review of Alabama History, Vol. ?? (April): ?? - ?? Burgin, Maggie (1931). The Direct Primary System in Alabama. -

A Canadian Model of Proportional Representation by Robert S. Ring A

Proportional-first-past-the-post: A Canadian model of Proportional Representation by Robert S. Ring A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Political Science Memorial University St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador May 2014 ii Abstract For more than a decade a majority of Canadians have consistently supported the idea of proportional representation when asked, yet all attempts at electoral reform thus far have failed. Even though a majority of Canadians support proportional representation, a majority also report they are satisfied with the current electoral system (even indicating support for both in the same survey). The author seeks to reconcile these potentially conflicting desires by designing a uniquely Canadian electoral system that keeps the positive and familiar features of first-past-the- post while creating a proportional election result. The author touches on the theory of representative democracy and its relationship with proportional representation before delving into the mechanics of electoral systems. He surveys some of the major electoral system proposals and options for Canada before finally presenting his made-in-Canada solution that he believes stands a better chance at gaining approval from Canadians than past proposals. iii Acknowledgements First of foremost, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my brilliant supervisor, Dr. Amanda Bittner, whose continuous guidance, support, and advice over the past few years has been invaluable. I am especially grateful to you for encouraging me to pursue my Master’s and write about my electoral system idea. -

Legislature by Lot: Envisioning Sortition Within a Bicameral System

PASXXX10.1177/0032329218789886Politics & SocietyGastil and Wright 789886research-article2018 Special Issue Article Politics & Society 2018, Vol. 46(3) 303 –330 Legislature by Lot: Envisioning © The Author(s) 2018 Article reuse guidelines: Sortition within a Bicameral sagepub.com/journals-permissions https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329218789886DOI: 10.1177/0032329218789886 System* journals.sagepub.com/home/pas John Gastil Pennsylvania State University Erik Olin Wright University of Wisconsin–Madison Abstract In this article, we review the intrinsic democratic flaws in electoral representation, lay out a set of principles that should guide the construction of a sortition chamber, and argue for the virtue of a bicameral system that combines sortition and elections. We show how sortition could prove inclusive, give citizens greater control of the political agenda, and make their participation more deliberative and influential. We consider various design challenges, such as the sampling method, legislative training, and deliberative procedures. We explain why pairing sortition with an elected chamber could enhance its virtues while dampening its potential vices. In our conclusion, we identify ideal settings for experimenting with sortition. Keywords bicameral legislatures, deliberation, democratic theory, elections, minipublics, participation, political equality, sortition Corresponding Author: John Gastil, Department of Communication Arts & Sciences, Pennsylvania State University, 232 Sparks Bldg., University Park, PA 16802, USA. Email: [email protected] *This special issue of Politics & Society titled “Legislature by Lot: Transformative Designs for Deliberative Governance” features a preface, an introductory anchor essay and postscript, and six articles that were presented as part of a workshop held at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, September 2017, organized by John Gastil and Erik Olin Wright. -

Engineering Electoral Systems: Possibilities and Pitfalls

Alan Wall and Mohamed Salih Engineering Electoral Systems: Possibilities and Pitfalls 1 Indonesia – Voting Station 2005 Index 1 Introduction 5 2 Engineering Electoral Systems: Possibilities and Pitfalls 6 2.1 What Is Electoral Engineering? 6 2.2 Basic Terms and Classifications 6 2.3 What Are the Potential Objectives of an Electoral System? 8 3 2.4 What Is the Best Electoral System? 8 2.5 Specific Issues in Split or Post Conflict Societies 10 2.6 The Post Colonial Blues 10 2.7 What Is an Appropriate Electoral System Development or Reform Process? 11 2.8 Stakeholders in Electoral System Reform 13 2.9 Some Key Issues for Political Parties 16 3 Further Reading 18 4 About the Authors 19 5 About NIMD 20 Annex Electoral Systems in NIMD Partner Countries 21 Colophon 24 4 Engineering Electoral Systems: Possibilities and Pitfalls 1 Introduction 5 The choice of electoral system is one of the most important decisions that any political party can be involved in. Supporting or choosing an inappropriate system may not only affect the level of representation a party achieves, but may threaten the very existence of the party. But which factors need to be considered in determining an appropriate electoral system? This publication provides an introduction to the different electoral systems which exist around the world, some brief case studies of recent electoral system reforms, and some practical tips to those political parties involved in development or reform of electoral systems. Each electoral system is based on specific values, and while each has some generic advantages and disadvantages, these may not occur consistently in different social and political environments. -

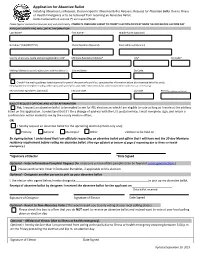

Application for Absentee Ballot

Application for Absentee Ballot Including Absentee List Request, Election Specific Absentee Ballot Request, Request for Absentee Ballot Due to Illness or Health Emergency or to be removed from receiving an Absentee Ballot. Fields marked with an asterisk (*) are required fields. Please type or use black or blue pen only and print clearly. COMPLETE FORM AND SUBMIT TO COUNTY ELECTION OFFICE BY NOON THE DAY BEFORE ELECTION DAY APPLICANT IDENTIFYING AND CONTACT INFORMATION Last Name* First Name* Middle Name (Optional) Birthdate* (MM/DD/YYYY) Phone Number (Optional) Email Address (Optional) County where you reside and are registered to vote* Montana Residence Address* City* Zip Code* Mailing Address (required if differs from residence address*) City and State Zip Code Check if the mailing address listed above is for part of the year only and if so, complete the information below (for absentee ballot list only). Clearly print the complete mailing address(es) and specify the applicable time periods for address (add more addresses as necessary). Seasonal Mailing Address (Optional) City and State Zip Code Period (mm/dd/yyyy-mm/dd/yyyy) BALLOT REQUEST OPTIONS AND VOTER AFFIRMATION Yes, I request an absentee ballot to be mailed to me for ALL elections in which I am eligible to vote as long as I reside at the address listed on this application. I understand that if I file a change of address with the U.S. postal service, I must complete, sign, and return a confirmation notice mailed to me by the county election office; OR I hereby request an absentee ballot for the upcoming election (check only one): Primary General Municipal Other election to be held on By signing below, I understand that I am officially requesting an absentee ballot and affirm that I will have met the 30-day Montana residency requirement before voting my absentee ballot. -

Voting Procedures and Their Properties

Voting Theory AAAI-2010 Voting Procedures and their Properties Ulle Endriss 8 Voting Theory AAAI-2010 Voting Procedures We’ll discuss procedures for n voters (or individuals, agents, players) to collectively choose from a set of m alternatives (or candidates): • Each voter votes by submitting a ballot, e.g., the name of a single alternative, a ranking of all alternatives, or something else. • The procedure defines what are valid ballots, and how to aggregate the ballot information to obtain a winner. Remark 1: There could be ties. So our voting procedures will actually produce sets of winners. Tie-breaking is a separate issue. Remark 2: Formally, voting rules (or resolute voting procedures) return single winners; voting correspondences return sets of winners. Ulle Endriss 9 Voting Theory AAAI-2010 Plurality Rule Under the plurality rule each voter submits a ballot showing the name of one alternative. The alternative(s) receiving the most votes win(s). Remarks: • Also known as the simple majority rule (6= absolute majority rule). • This is the most widely used voting procedure in practice. • If there are only two alternatives, then it is a very good procedure. Ulle Endriss 10 Voting Theory AAAI-2010 Criticism of the Plurality Rule Problems with the plurality rule (for more than two alternatives): • The information on voter preferences other than who their favourite candidate is gets ignored. • Dispersion of votes across ideologically similar candidates. • Encourages voters not to vote for their true favourite, if that candidate is perceived to have little chance of winning. Ulle Endriss 11 Voting Theory AAAI-2010 Plurality with Run-Off Under the plurality rule with run-off , each voter initially votes for one alternative. -

EU Electoral Law Memorandum.Pages

Memorandum on the Electoral Law of the European Union: Confederal and Federal Legitimacy and Turnout European Parliament Committee on Constitutional Affairs Hearing on Electoral Reform Brendan O’Leary, BA (Oxon), PhD (LSE) Lauder Professor of Political Science, University of Pennsylvania Citizen of Ireland and Citizen of the USA1 submitted November 26 2014 hearing December 3 2014 Page !1 of !22 The European Parliament, on one view, is a direct descendant of its confederal precursor, which was indirectly elected from among the member-state parliaments of the ESCC and the EEC. In a very different view the Parliament is the incipient first chamber of the European federal demos, an integral component of a European federation in the making.2 These contrasting confederal and federal understandings imply very different approaches to the law(s) regulating the election of the European Parliament. 1. The Confederal Understanding In the confederal vision of Europe as a union of sovereign member-states, each member- state should pass its own electoral laws, execute its own electoral administration, and regulate the conduct of its representatives in European institutions, who should be accountable to member- state parties and citizens, and indeed function as their “mandatable” delegates. In the strongest confederal vision, in the conduct of EU law-making and policy MEPs should have less powers and status than the ministers of member-states, and their delegated authorities (e.g., ambassadors, or functionally specialized civil servants). In most confederal visions MEPs should be indirectly elected from and accountable to their home parliaments. Applied astringently, the confederal understanding would suggest that the current Parliament has been mis-designed, and operating beyond its appropriate functions at least since 1979. -

Chapter 6 Michigan's Absentee Voting Process

ELECTION OFFICIALS’ MANUAL Michigan Bureau of Elections Chapter 6, October 2020 Chapter 6 Michigan’s Absentee Voting Process TABLE OF CONTENTS Note on October 2020 Updates .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Eligibility ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Application Process: ..................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Maintaining a Permanent Absent Voter Application List ............................................................................................................. 4 Submission of Absent Voter Ballot Applications .......................................................................................................................... 4 Office Hours on Saturday and/or Sunday Preceding Election ...................................................................................................... 5 Restrictions on Possession of Signed Absentee Ballot Applications ............................................................................................ 6 Application Verification Requirement ......................................................................................................................................... 6 Issuance of Absentee -

The Parliamentary Electoral System in Denmark

The Parliamentary Electoral System in Denmark GUIDE TO THE DANISH ELECTORAL SYSTEM 00 Contents 1 Contents Preface ....................................................................................................................................................................................................3 1. The Parliamentary Electoral System in Denmark ..................................................................................................4 1.1. Electoral Districts and Local Distribution of Seats ......................................................................................................4 1.2. The Electoral System Step by Step ..................................................................................................................................6 1.2.1. Step One: Allocating Constituency Seats ......................................................................................................................6 1.2.2. Step Two: Determining of Passing the Threshold .......................................................................................................7 1.2.3. Step Three: Allocating Compensatory Seats to Parties ...........................................................................................7 1.2.4. Step Four: Allocating Compensatory Seats to Provinces .........................................................................................8 1.2.5. Step Five: Allocating Compensatory Seats to Constituencies ...............................................................................8