Franklin Pipe Organs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

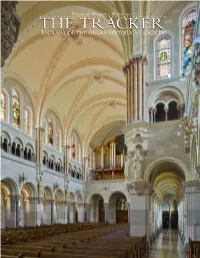

The Tracker the Tracker

Volume 56, Number 1, Winter 2012 THE TRACKER JOURNAL OF THE ORGAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY WELCOME TO CHICAGO! CHICAGO IS A WORLD-CLASS CITY that offers much to see and do—including fine dining, many museums, attractions, and events, and shopping. Allow time to savor the sights and sounds of this Come to vibrant city and make your convention trip truly un- forgettable! The 2012 Convention is presented by the Chicago-Midwest Chapter, which brought you the Chicago 2002 convention. We couldn’t fit all the wondrous organs and venues into just one convention—so make sure you don’t miss this opportunity to visit FOR OHS 2012 the City of Big Shoulders—and Big Sounds! July 8-13 † CITY OF BIG SOUNDS PHOTOS WILLIAM T. VAN PELT WHY CHICAGO? THE CONVENTION WILL COMPLETE what the 2002 con- vention started—demonstrating more of Chicago’s dis- tinguished pipe organs, from newer, interesting instru- ments that are frequent participants in Chicago’s music life, to hidden gems that have long been silent. The Convention events cover the length and breadth of the Chicago area, including northern Indiana venues, and include an evening boat cruise for viewing the mag- nificent Chicago skyline while you dine. PERFORMERS Recitalists include many of the Chicago area’s leading organists, along with artists familiar to OHS audiences from previous conventions. Many players have a Chicago connection, and the recit- als often feature younger players. CONVENTION ORGANS C.B. Fisk Casavant Frères, Limitée Hook & Hastings Hinners Organ Co. Skinner Organ Co. Wurlitzer Aeolian-Skinner Organ Co. Noack M.P. -

2017 Pipe Organ Report

ORGAN REPORT 2604 N. Swan Blvd., Wauwatosa, WI 53226 JUNE 1, 2017 “Beauty evangelizes, and a new organ will strengthen the Christ King mission to proclaim Christ and make disciples in the world.” Table of Contents A Letter From the Organ Committee.................Pg. 2 The Organ Committee Process..........................Pg. 3 Addendum 1 of 2: Riedel Organ Condition Report..................Pg. 4-15 Addendum 2 of 2: Type of Organs.............................................Pg.16-20 From theTHE Committee... PIPE ORGAN AT CHRIST KING PARISH The Organ Committee at Christ King Parish was formed in 2015 at the request of the Pastoral Council and the Worship Committee to evaluate the condition of our current organ, plus its present and future role in our community. This report will provide details on the failing condition of our organ, the cost for refurbishment vs the cost of replacing the instrument and the vetting of organ building companies. In 2007, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) issued a document entitled, “Sing to the Lord: Music in Divine Worship”. Drawing from several centuries of organ use in the Catholic Church the Bishops stated the following about organs: 87. Among all other instruments which are suitable for divine worship, the organ is “accorded pride of place” because of its capacity to sustain the singing of a large gathered assembly, due to both its size and its ability to give “resonance to the fullness of human sentiments, from joy to sadness, from praise to lamentation.” Likewise,” the manifold possibilities of the organ in some way remind us of the immensity and the magnificence of God” 88. -

Christine Jakobi- Mirwald

CHRISTINE JAKOBI-MIRWALD Initials and other Elements of Minor Decoration C H R I S T I N E J AKOBI -M IRWALD A paper on the subject of minor manuscript decoration can well turn out somewhat less than exciting. However, it depends on the point of view, and if the manuscripts of the Liber Extra are a somewhat alien field of investigation to this author, 1 this may well present a chance for a fresh approach. For once, the subject of terminologies in different languages has recently proved to be rather fascinating. 2 In the third edition of my Terminology * I would like to thank Martin Bertram for trusting me with this paper and for acce pting it at the conference, even when I was unable to participate in person, and Susanne Wittekind, who was so kind as to read the text in my place. 1 My primary fields of research have concentrated on rather earlier manuscripts: Die illuminierten Han dschr iften der Hessischen Landesbibliothek Fulda. 1. Handschriften des 6. – 13. Jahrhunderts. Textband bea rbeitet von Ch. J AKOBI - M IRWALD auf Grund der Vorarbeiten von Herbert Köllner, Denkmäler der Buchkunst 10, Stuttgart 1993; C. J AKOBI - M IRWALD , Die Initiale zu r Causa 28 in den Münchener Gratianhandschriften 17161 und 23551, in: E. E ISENLOHR , P. W O R M (Hg.), Arbeiten aus dem Marbu rger hilfswissenschaftlichen Institut, Elementa diplomatica 8, Marburg 2000, p. 217 -228; E AD. Die Schäftlarner Gratian - Handschrift Clm 17161 in der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, Münchner Jahrbuch der bildende n Kunst, 3. F. 58 (2007), p. -

Trinity's Organ

Trinity’s Organ The organ at Trinity was dedicated on October 23, 1994. In many ways it can be thought of as a reflection of our own congregation. There are 2,395 pipes in the organ. Trinity congregation, in 1994 was very close to that number in membership and has since then far surpassed it. The pipes in the organ actually form a “congregation of singers” made up of many different shapes and sizes. Some are short, some are tall. Some sing high, some sing low. Some are loud, some are soft. Each person in our sanctuary can combine his or her voice with others to offer up prayers and songs of praise. Each pipe in the organ “building” works along side of others to produce sounds for accompanying our songs of praise. We each have a mouth to sing God’s praise. Each pipe in the organ also has a mouth. The straight edge at the top of a pipe’s mouth is called the upper lip. The bottom edge is the lower lip. Pipes have “feet”, “bodies”, “ears”, and “tongues.” The pipes “sing” in much the same way as humans. Sound is produced when air causes something to vibrate. The sound then comes out through a mouth for all to hear. The pipes receive their breath for singing from a windchest. The sound produced by the pipes is thus a sound that is vibrant – “alive”! The organ at Trinity is an instrument allowed by God to be built for worship – an instrument whose breath will combine with ours to set in motion pipes for praise. -

Carl Barckhoff and the Barckhoff Church Organ Company

Volume 39, Number 4, 1995 Founded in 1956 CARL BARCKHOFF AND THE BARCKHOFF CHURCH ORGAN COMPANY Carl Barckhoff - about 1880 by Vernon Brown Reprinted from The Tracker, 22:4 (Summer, 1978) Carl Barckhoff, one of the foremost Midwest late 19th 1880, "the church filled with a fashionable and cultured and early 20th century organ builders, was born in audience," 2 Carl himself played. Cora Hawley, the Wiedenbruck, Westphalia, Germany, in 1849. His father, daughter of an influencial man in Salem, was the soprano organ builder Felix Barckhoff, brought the family to the soloist, and this marked the beginning of a romance United States in 1865, and in that same year the first between Barckhoff and Miss Hawley. Barckhoff organ was built in this country. The firm In 1881 Carl married Miss Hawley, and in 1882, having established at 1240 Hope Street, Philadelphia, was for a time obtained financial backing locally, he relocated the during the 1870's known as Felix Barckhoff & Sons, the sons Barckhoff Church Organ Company in Salem. The new being Carl and Lorenz. factory at 31 Vine Street "had an organ hall 35 feet high, Felix Barckhoff died in 1878, 1 and at about this same time which made it possible to construct the largest organs built Carl relocated the firm in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, at that time. According to records, most of the men in an area which is today North Side Pittsburgh. An organ employed by Mr. Barckhoff had learned their trade in for the Presbyterian Church of Salem, Ohio was built in this Germany. -

'The Expressive Organ Within Us:' Ether, Ethereality, And

CARMEL RAZ Music and the Nerves “The Expressive Organ within Us”: Ether, Ethereality, and Early Romantic Ideas about Music and the Nerves CARMEL RAZ In Honoré de Balzac’s novel Le Lys dans la sounds without melody, and cries that are lost in Vallée (1835), Felix de Vandenesse courts solitude.1 Henriette de Mortsauf by implying that their souls have a sympathetic connection. Katherine Prescott Wormeley’s translation ren- ders “un orgue expressif doué de mouvement” We belong to the small number of human beings as “the organ within us endowed with expres- born to the highest joys and the deepest sorrows; sion and motion.” This word choice omits the whose feeling qualities vibrate in unison and echo author’s pun on the expressive organ, here serv- each other inwardly; whose sensitive natures are in ing as both a metaphor for the brain and a harmony with the principle of things. Put such be- reference to the recently invented harmonium ings among surroundings where all is discord and instrument of the same name, the orgue they suffer horribly. The organ within us en- expressif.2 Balzac’s wordplay on the expressive dowed with expression and motion is exercised in a organ represents an unexpected convergence of void, expends its passion without an object, utters music, organology, natural science, and spiri- tualism. A variety of other harmoniums popu- I would like to thank Patrick McCreless, Brian Kane, Paola Bertucci, Anna Zayaruznaya, Courtney Thompson, Jenni- 1Honoré de Balzac, The Lily of the Valley, trans. Katharine fer Chu, Allie Kieffer, Valerie Saugera, Nori Jacoby, and P. -

Seeking Cavaillé-Coll Organs in North America We Are Forging Ahead, Indeed, and with No Little Palatable AGNES ARMSTRONG Success

VOLUME 59, NUMBER 1, WINTER 2015 THE TRACKER JOURNAL OF THE ORGAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY ORGAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY•JUNE 28-JULY 3 THE PIONEER VALLEY - WESTERN MASS. Join us for the 60th Annual OHS Convention, and our first visit to this cradle of American organbuilding. WILLIAM JACKSON (1868) CASAVANT FRÈRES LTÉE. (1897) C.B. FISK (1977) JOHNSON & SON (1892) JOHNSON & SON (1874) EMMONS HOWARD (1907) Come! Celebrate! Explore! ALSO SHOWCASING THE WORK OF HILBORNE ROOSEVELT, E. & G.G. HOOK, AEOLIAN-SKINNER, AND ANDOVER ORGAN WWW.ORGANSOCIETY.ORG/2015 SKINNER ORGAN CO. (1921) HILBORNE L. ROOSEVELT (1883) 2015 E. POWER BIGGS FELLOWSHIP HONORING A NOTABLE ADVOCATE FOR examining and understanding the pipe or- DEADLINE FOR APPLICATIONS gan, the E. Power Biggs Fellows will attend is February 28, 2015. Open to women the OHS 60th Convention in the Pioneer and men of all ages. To apply, go to Valley and the Berkshires of Western Mas- HTTP: // BIGGS.ORGANSOCIETY.ORG sachusetts, June 28 – July 3, 2015, with headquarters in Springfield, Mass. Hear and experience a wide variety of pipe or- gans in the company of organ builders, professional musicians and enthusiasts. 2015 COMMITTEE The Fellowship includes a two-year member- SAMUEL BAKER CHAIR TOM GIBBS VICE CHAIR ship in the OHS and covers these convention costs: GREGORY CROWELL CHRISTA RAKICH ♦ Travel ♦ Meals PAUL FRITTS PRISCILLA WEAVER ♦ ♦ Hotel Registration LEN LEVASSEUR LEN ORGAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY WWW.ORGANSOCIETY.ORG PHOTOS J.W. STEERE & SON (1902) A DAVID MOORE INC World-Class Tracker Organs Built in Vermont Photos Courtesy of J. O. Love A Gem Rises We are pleased to announce that our Opus 37 is nearing completion at St Paul Catholic Parish, Pensacola, Florida. -

Howe Collection of Musical Instrument Literature ARS.0167

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8cc1668 No online items Guide to the Howe Collection of Musical Instrument Literature ARS.0167 Jonathan Manton; Gurudarshan Khalsa Archive of Recorded Sound 2018 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/ars Guide to the Howe Collection of ARS.0167 1 Musical Instrument Literature ARS.0167 Language of Material: Multiple languages Contributing Institution: Archive of Recorded Sound Title: Howe Collection of Musical Instrument Literature Identifier/Call Number: ARS.0167 Physical Description: 438 box(es)352 linear feet Date (inclusive): 1838-2002 Abstract: The Howe Collection of Musical Instrument Literature documents the development of the music industry, mainly in the United States. The largest known collection of its kind, it contains material about the manufacture of pianos, organs, and mechanical musical instruments. The materials include catalogs, books, magazines, correspondence, photographs, broadsides, advertisements, and price lists. The collection was created, and originally donated to the University of Maryland, by Richard J. Howe. It was transferred to the Stanford Archive of Recorded Sound in 2015 to support the Player Piano Project. Stanford Archive of Recorded Sound, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California 94305-3076”. Language of Material: The collection is primarily in English. There are additionally some materials in German, French, Italian, and Dutch. Arrangement The collection is divided into the following six separate series: Series 1: Piano literature. Series 2: Organ literature. Series 3: Mechanical musical instruments literature. Series 4: Jukebox literature. Series 5: Phonographic literature. Series 6: General music literature. Scope and Contents The Howe Musical Instrument Literature Collection consists of over 352 linear feet of publications and documents comprising more than 14,000 items. -

Class Thesaurus Headings

Hofmeister XIX: Class thesaurus headings Ensemble Ensemble (small) Iconography Keyboard (other) Literature Miscellaneous Not classified Orchestra Pedagogical Percussion Piano (ensemble) Piano (multiple) Piano (solo) Sacred music Strings (bowed) Strings (general) Strings (plucked) Voice (multiple) Voice (solo) Voice (unspecified) Wind (brass) Wind (free reed) Wind (woodwind) Hofmeister XIX: class thesaurus terms Category English translation Class in Hofmeister thesaurus Ensemble Concertante works with orchestra or string quartet. Concertanten mit Orchester oder Streichquartett. Concertante works with orchestra or string quintet or string Concertanten mit Orchester oder Streichquintett oder quartet. Streichquartett. Concertante works with orchestra or string quintet. Concertanten mit Orchester oder Streichquintett. Concertante works with orchestra. Concertanten mit Orchester. Concertante works with string quartet. Concertanten mit Streichquartett. Concertante works with string quintet. Concertanten mit Streichquintett. Music for children's instruments. Musik für Kinderinstrumente. Music for military band. Harmoniemusik (Militär) für Blasinstrumente. Music for string and wind instruments. Musik für Streich- und Blasinstrumente. Music for string, wind and percussion instruments. Musik für Streich-, Blas- und Schlaginstrumente. Ensemble (small) Music for accordion and harmonic flute. Musik für das Accordion und Harmonieflöte. Music for harmonic flute and single-action accordion. Musik für die Harmonieflöte und Handharmonika. Music for harmonium -

A PROFILE of CHARLES M. RUGGLES, BUILDER of HAND-CRAFTED MECHANICAL ACTION ORGANS by Mark A. Herris Submitted to the Faculty Of

A PROFILE OF CHARLES M. RUGGLES, BUILDER OF HAND-CRAFTED MECHANICAL ACTION ORGANS by Mark A. Herris Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2016 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Janette Fishell, Research Director ______________________________________ Christopher Young, Chair ______________________________________ Eric J. Isaacson ______________________________________ Elisabeth Wright April 6, 2016 ii Copyright © 2016 Mark A. Herris iii Dedicated to Christy, Ryan, and Sam iv Acknowledgements I am thankful for all of the support I have received in completing this project. It has been an honor to work extensively with Charles M. Ruggles over the past several months, and this project would not have been possible without his substantial support and time. I would like to thank my research director, Professor Janette Fishell, for her feedback and direction as this project came to fruition. I cannot thank her enough for challenging me to do my best. I am also indebted to Professors Christopher Young, Eric J. Isaacson, and Elizabeth Wright for graciously agreeing to serve on the committee for this paper. I am grateful for my organ teachers who have helped me get to this point, including Christopher Young, Craig Cramer, Gail Walton, and Jack Vogelgesang. I would like to acknowledge David Kazimir and Bob Finley for their assistance in developing my understanding of organ building. Special thanks goes to Leslie Weaver for her expeditious editing of my paper. -

THE ACCORDION and the BOOK by Peter Thomas a Bit Over a Decade Ago, I Had the Idea to Make an Accordion Book

Peter and Donna Thomas. This real accordion book was made in the spring of 2016. The images and text were digitally printed on Peter’s handmade paper and then hand-colored by Donna. Peter: “I bought the Hohner accordion at the Cotati Accordion Festival. It was so beautiful, but no longer could be played, and thus a perfect candidate for becom- ing an accordion book.” THE ACCORDION AND THE BOOK by Peter Thomas A bit over a decade ago, I had the idea to make an accordion book. The book would use the accordion keyboards as covers and the bellows would be cut along the vertical ends, so that when pulled open, it would look like a real accordion book! I play the accordion and couldn’t pass up the opportunity presented by the visual pun, but the real purpose for making the book was to address a point of confusion among book artists: whether a folded paper book should be called an “accordion book” or a “con- certina book.” From playing both musical instruments, I knew that an accordion is rectangular and a concertina is hexagonal. So I made my first real accordion book in tandem with a book made out of a concertina to physically explain why, unless a book is hexagonal in shape, the correct term is accordion book. That first accordion book was followed by another, then another, creating a series. I don’t know exactly how many Donna and I have made so far. After one sells, we make another. As a series, the works are tied together by structure, text, and image. -

1950-01-29 University of Notre Dame Commencement Program

105th Annual Commencement JANUARY EXERCISES ............"'U.l~tz:~""·:;;"';'"\.'7·(~ ..... ~.:.:...•.;;.,:_:;,~-;~~;~·'!:" THE UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME NOTRE DAME, INDIANA THE GRADUATE ScHooL THE CoLLEGE OF ARTS AND LETTERS THE CoLLEGE· OF SciENCE THE CoLLEGE OF ENGINEERING THE CoLLEGE OF LAw. THE COLLEGE OF COMl'vfERCE In the University Drill Hall At 2:00 p.m. January 29, 1950 ~.~-~--------------------------------------~----------------------~ ,--------- - PROGRAM Processional The Conferring of Degrees, by the Rev. John J. Cavanaugh, C.S.C., President of the University Commencement Address, by the Ron. John Fitzgerald Kennedy of Hyannisport, Massachusetts The Blessing, by the Most Rev. Joseph Elmer Ritter, Archbishop :of St. Louis, Missouri National Anthem 3 Degrees Conferred The University of Notre Dame announces the conferring of the degree of Doctor of Laws, honoris causa, on: The Most Reverend Joseph Elmer Ritter, of St. Louis, Missouri. Rear Admiral James Lemuel Holloway, U.S.N., of Annapolis, Maryland. The Honorable John Fitzgerald Kennedy, of Hyannisport, Massachusetts~ IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL The University of Notre Dame confers the following degrees in course: The Degree of Master o/ Arts on: VRev. Joseph Thomas Engleton, of the Congregation of Holy Cross, Notre Dame, Indiana ' A.B., University of Notre Dame, 1943. Major subject: History. Dis sertation: George W. Julian and the Know-Nothing Movement in Indiana, 1840-1860. Rev. Paul Edward Fryberger, of the Congregation of Holy Cross, Notre Dame, Indiana A.B., University of Notre Dame, 1932. Major subject: Economics. Dis sertation: The Doctrine on Wages in the Social Encyclicals. Robert Staunton Berringer, South Bend, Indiana A.B., Ball State Teachers College, 1939. Major subject: Classics.