Anaxyrus Fowleri) in a Cranberry (Vaccinium Macrocarpon) Bog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Veterans Park Herpetological Report Manning 2015

To Whom It May Concern, The information in this document is the summary of a series of volunteer reptile and amphibian observations conducted in Hamilton Veteran’s Park in Mercer County, NJ. The document has been prepared for the Township of Hamilton. The results presented are from field observations and data collected in 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015. The data from the first three years was taken informally during morning and evening walks with family. The data from 2015 was taken for a volunteer reptile and amphibian survey performed upon the request of the Township of Hamilton, Mercer County, NJ. This information is presented voluntarily for use in conservation endeavors. General Profile: Hamilton Veteran’s Park is a 350‐acre park managed by the Township of Hamilton in Mercer County, New Jersey. The park features a diversity of habitats within its boundaries, including a field which was the site of a former farm, a wetlands meadow, a smaller upland meadow, several patches of deciduous forest, a man‐made lake, temporary and permanent wetlands, an intermittent stream, and several permanent streams. The park is located on the physiographic province known as the inner coastal plain. Comments on General Fauna: The Veteran’s Park property provides a variety of habitats for native fauna to flourish. Healthy numbers of invertebrates have been observed during the survey. Checking under logs and other cover debris reveals a multitude of native decomposers, such as ants, earthworms, slugs, centipedes, harvestmen, and others. Ticks are occasionally seen in the fields, however most of those observed were dog ticks. -

Mitochondrial Discordance and Gene Flow in a Recent Radiation of Toads

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 59 (2011) 66–80 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Nuclear–mitochondrial discordance and gene flow in a recent radiation of toads ⇑ Brian E. Fontenot , Robert Makowsky 1, Paul T. Chippindale Department of Biology, University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, TX 76019, United States article info abstract Article history: Natural hybridization among recently diverged species has traditionally been viewed as a homogenizing Received 28 April 2010 force, but recent research has revealed a possible role for interspecific gene flow in facilitating species Revised 12 December 2010 radiations. Natural hybridization can actually contribute to radiations by introducing novel genes or Accepted 23 December 2010 reshuffling existing genetic variation among diverging species. Species that have been affected by natural Available online 19 January 2011 hybridization often demonstrate patterns of discordance between phylogenies generated using nuclear and mitochondrial markers. We used Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism (AFLP) data in conjunc- Keywords: tion with mitochondrial DNA in order to examine patterns of gene flow and nuclear–mitochondrial dis- Toads cordance in the Anaxyrus americanus group, a recent radiation of North American toads. We found high Hybridization Gene flow levels of gene flow between putative species, particularly in species pairs sharing similar male advertise- Speciation ment calls that occur in close geographic proximity, suggesting that prezygotic reproductive isolating AFLPs mechanisms and isolation by distance are the primary determinants of gene flow and genetic differenti- Nuclear–mitochondrial discordance ation among these species. Additionally, phylogenies generated using AFLP and mitochondrial data were markedly discordant, likely due to recent and/or ongoing natural hybridization events between sympatric populations. -

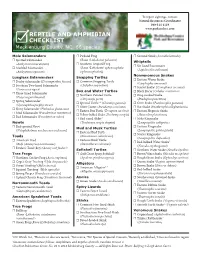

Checklist Reptile and Amphibian

To report sightings, contact: Natural Resources Coordinator 980-314-1119 www.parkandrec.com REPTILE AND AMPHIBIAN CHECKLIST Mecklenburg County, NC: 66 species Mole Salamanders ☐ Pickerel Frog ☐ Ground Skink (Scincella lateralis) ☐ Spotted Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) palustris) Whiptails (Ambystoma maculatum) ☐ Southern Leopard Frog ☐ Six-lined Racerunner ☐ Marbled Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) sphenocephala (Aspidoscelis sexlineata) (Ambystoma opacum) (sphenocephalus)) Nonvenomous Snakes Lungless Salamanders Snapping Turtles ☐ Eastern Worm Snake ☐ Dusky Salamander (Desmognathus fuscus) ☐ Common Snapping Turtle (Carphophis amoenus) ☐ Southern Two-lined Salamander (Chelydra serpentina) ☐ Scarlet Snake1 (Cemophora coccinea) (Eurycea cirrigera) Box and Water Turtles ☐ Black Racer (Coluber constrictor) ☐ Three-lined Salamander ☐ Northern Painted Turtle ☐ Ring-necked Snake (Eurycea guttolineata) (Chrysemys picta) (Diadophis punctatus) ☐ Spring Salamander ☐ Spotted Turtle2, 6 (Clemmys guttata) ☐ Corn Snake (Pantherophis guttatus) (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus) ☐ River Cooter (Pseudemys concinna) ☐ Rat Snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) ☐ Slimy Salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) ☐ Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) ☐ Eastern Hognose Snake ☐ Mud Salamander (Pseudotriton montanus) ☐ Yellow-bellied Slider (Trachemys scripta) (Heterodon platirhinos) ☐ Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber) ☐ Red-eared Slider3 ☐ Mole Kingsnake Newts (Trachemys scripta elegans) (Lampropeltis calligaster) ☐ Red-spotted Newt Mud and Musk Turtles ☐ Eastern Kingsnake -

American Toad (Anaxyrus Americanus) Fowler's Toad (Anaxyrus Fowleri

Vermont has eleven known breeding species of frogs. Their exact distributions are still being determined. In order for these species to survive and flourish, they need our help. One way you can help is to report the frogs that you come across in the state. Include in your report as much detail as you can on the appearance and location of the animal; also include the date of the sighting, your name, and how to contact you. Photographs are ideal, but not necessary. When attempting to identify a particular species, check at least three different field markings so that you can be sure of what it is. To contribute a report, you may use our website (www.vtherpatlas.org) or contact Jim Andrews directly at [email protected]. American Bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) American Toad (Anaxyrus americanus) The American Bullfrog is our largest frog and can reach 7 inches long. The Bullfrog is one of the three The American Toad is one of Vermont’s two toad species. Toads can be distinguished from other green-faced frogs in Vermont. It has a green and brown mottled body with dark stripes across its legs. frogs in Vermont by their dry and bumpy skin, and the long oval parotoid glands on each side of their The Bullfrog does not have dorsolateral ridges, but it does have a ridge that starts at the eye and goes necks. The American Toad has at least one large wart in each of the large black spots found along its around the eardrum (tympana) and down. The Bullfrog’s call is a deep low jum-a-rum. -

Species Status Assessment Report for the Eastern Population of The

Species Status Assessment Report for the Eastern Population of the Boreal Toad, Anaxyrus boreas boreas Prepared by the Western Colorado Ecological Services Field Office U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Grand Junction, Colorado EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This species status assessment (SSA) reports the results of the comprehensive biological status review by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) for the Eastern Population of the boreal toad (Anaxyrus boreas boreas) and provides a thorough account of the species’ overall viability and, therefore, extinction risk. The boreal toad is a subspecies of the western toad (Anaxyrus boreas, formerly Bufo boreas). The Eastern Population of the boreal toad occurs in southeastern Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, northern New Mexico, and most of Utah. This SSA Report is intended to provide the best available biological information to inform a 12-month finding and decision on whether or not the Eastern Population of boreal toad is warranted for listing under the Endangered Species Act (Act), and if so, whether and where to propose designating critical habitat. To evaluate the biological status of the boreal toad both currently and into the future, we assessed a range of conditions to allow us to consider the species’ resiliency, redundancy, and representation (together, the 3Rs). The boreal toad needs multiple resilient populations widely distributed across its range to maintain its persistence into the future and to avoid extinction. A number of factors influence whether boreal toad populations are considered resilient to stochastic events. These factors include (1) sufficient population size (abundance), (2) recruitment of toads into the population, as evidenced by the presence of all life stages at some point during the year, and (3) connectivity between breeding populations. -

Signs of the Seasons: a New England Phenology Program Indicator

Signs of the Seasons: A New England Phenology Program Indicator Species Fact Sheet Eastern American Toad, Anaxyrus americanus The American toad is commonly found throughout New England and is native to eastern North America. Considered habitat generalists, these toads can be found anywhere that moisture and ample food are available, including multiple forest types, fields and urban areas. Toads play an important ecosystem role as insect consumers, thereby keeping populations in check. Appearance: Toads are shades of brown in color and are covered with warts. They have a wide head and short front limbs. Behind the eyes, there are kidney bean shaped glands; J.D. Willson, USGS Savannah River Ecology Lab, http://srel.uga.edu/ these paratoid glands produce toxins that give the toad an unpleasant taste. The toads range in length from 2-4 ½ inches. Females are slightly larger than males and lack the characteristic dark colored throat seen on males. Feeding: American toads are known to feed from early morning into the evening. They consume what is available and may eat a variety of larval insects, slugs, spiders, and centipedes, for example. Tadpoles feed on algae within their pools. Life History: Breeding season is triggered by the arrival of warmer temperatures and longer days. It begins in March or April when the toads arrive at shallow, fresh water pools. Males grasp the females around the belly in order to fertilize the eggs as they are laid. Between 4,000-12,000 eggs are laid in long parallel strands. They will hatch in 3-12 days, requiring 5-10 weeks to complete metamorphosis and 2-4 years to reach sexual maturity. -

Annotated Checklist of Amphibian and Reptile Species Observed at the Gordon Natural Area (West Chester University, PA) 2008-2020

West Chester University Digital Commons @ West Chester University Gordon Natural Area Biodiversity Studies Documents Gordon Natural Area Biodiversity Studies 7-28-2020 Annotated Checklist of Amphibian and Reptile Species Observed at the Gordon Natural Area (West Chester University, PA) 2008-2020. Version I Nur Ritter Harry Tiebout Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/gna_bds_series Part of the Biodiversity Commons Annotated Checklist of Amphibian and Reptile Species Observed at the Gordon Natural Area (West Chester University, PA) 2008-2020. Version I Summary Data Number of Taxa: Species, in 14 Genera, 6 Families, and 4 Orders. Description Data were compiled from surveys by Dr. Harry Tiebout, augmented by observations from GNA staff (which, as used here, includes student interns), graduate student Steven Clay, the Stroud Water Research Center, additional WCU Faculty, and members of the WCU Grounds Department. Local residents who are regular visitors to the Gordon have also occasionally contributed observations. Because herptile data haven't been systematically archived by the GNA staff until recent years, there are many gaps in the observation timeline that are clearly artificial. For example, although the observation history for the Eastern American Toad, Eastern Redback Salamander, and Eastern Box Turtle suggests that there were a number of years in which one, or all, of these species were not seen at the GNA, it is very likely that all three of these species have been observed numerous times during every year that the GNA has been in existence. Hopefully, moving forward, we'll be able to maintain a more complete record of observations. -

Response of Reptile and Amphibian Communities to the Reintroduction of Fire T in an Oak/Hickory Forest ⁎ Steven J

Forest Ecology and Management 428 (2018) 1–13 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco Response of reptile and amphibian communities to the reintroduction of fire T in an oak/hickory forest ⁎ Steven J. Hromadaa, , Christopher A.F. Howeyb,c, Matthew B. Dickinsond, Roger W. Perrye, Willem M. Roosenburgc, C.M. Giengera a Department of Biology and Center of Excellence for Field Biology, Austin Peay State University, Clarksville, TN 37040, United States b Biology Department, University of Scranton, Scranton, PA 18510, United States c Ohio Center for Ecology and Evolutionary Studies, Department of Biological Sciences, Ohio University, Athens, OH 45701, United States d Northern Research Station, U.S. Forest Service, Delaware, OH 43015, United States e Southern Research Station, U.S. Forest Service, Hot Springs, AR 71902, United States ABSTRACT Fire can have diverse effects on ecosystems, including direct effects through injury and mortality and indirect effects through changes to available resources within the environment. Changes in vegetation structure suchasa decrease in canopy cover or an increase in herbaceous cover from prescribed fire can increase availability of preferred microhabitats for some species while simultaneously reducing preferred conditions for others. We examined the responses of herpetofaunal communities to prescribed fires in an oak/hickory forest in western Kentucky. Prescribed fires were applied twice to a 1000-ha area one and four years prior to sampling, causing changes in vegetation structure. Herpetofaunal communities were sampled using drift fences, and vegetation attributes were sampled via transects in four burned and four unburned plots. Differences in reptile community structure correlated with variation in vegetation structure largely created by fires. -

Wildlife in Your Young Forest.Pdf

WILDLIFE IN YOUR Young Forest 1 More Wildlife in Your Woods CREATE YOUNG FOREST AND ENJOY THE WILDLIFE IT ATTRACTS WHEN TO EXPECT DIFFERENT ANIMALS his guide presents some of the wildlife you may used to describe this dense, food-rich habitat are thickets, T see using your young forest as it grows following a shrublands, and early successional habitat. timber harvest or other management practice. As development has covered many acres, and as young The following lists focus on areas inhabited by the woodlands have matured to become older forest, the New England cottontail (Sylvilagus transitionalis), a rare amount of young forest available to wildlife has dwindled. native rabbit that lives in parts of New York east of the Having diverse wildlife requires having diverse habitats on Hudson River, and in parts of Connecticut, Rhode Island, the land, including some young forest. Massachusetts, southern New Hampshire, and southern Maine. In this region, conservationists and landowners In nature, young forest is created by floods, wildfires, storms, are carrying out projects to create the young forest and and beavers’ dam-building and feeding. To protect lives and shrubland that New England cottontails need to survive. property, we suppress floods, fires, and beaver activities. Such projects also help many other kinds of wildlife that Fortunately, we can use habitat management practices, use the same habitat. such as timber harvests, to mimic natural disturbance events and grow young forest in places where it will do the most Young forest provides abundant food and cover for insects, good. These habitat projects boost the amount of food reptiles, amphibians, birds, and mammals. -

Field Guide Field Journal Blanchard's Cricket Frog

Field Guide Frogs and Toads of the Washington, D.C. Area Field Journal Name: Date: Blanchard's cricket frog Location: Acris crepitans Baird, 1854 Weather: Time of Day: Observations / Data / Activity Overview General Description Acris crepitans is 1.6-3.5 cm long and has a blunt, pointed head with an occasional triangular marking. Its back and legs are covered with various dark markings. It has a middorsal bright green or brown stripe and the rear of its thigh has a distinct ragged dark stripe. A white bar extends from its eye to its foreleg. The body is slim-waisted and small while the skin is granular and warty. Hind toes are extensively webbed and toe pads are poorly developed (Stebbins 2003). Acris crepitans paludicola and Acris crepitans blanchardi are recognized as subspecies. A. c. paludicola has smooth skin with a pinkish patterned coloration. The throat Write down questions that you have for further exploration. remains pink, even for males during breeding season. A. c. blanchardi by comparison is wartier, bulkier, and heavier with a light brown or gray uniform coloration (Conant and Collins 1991). Males have more ventral spotting than females (Stebbins 2003). Distribution Unlike most small frogs in its range, A. c. crepitans does not leave the vicinity of water in its adult stage. It is found at the edge of ponds and slow-moving streams, tending to avoid wooded areas and dense vegetation (Hulse McCoy and Censky 2001). A. c. blanchardi is found in Michigan, Ohio, Nebraska, eastern Colorado, and most of Texas. A few have been spotted in Minnesota and New Mexico as well. -

Frogs and Toads Defined

by Christopher A. Urban Chief, Natural Diversity Section Frogs and toads defined Frogs and toads are in the class Two of Pennsylvania’s most common toad and “Amphibia.” Amphibians have frog species are the eastern American toad backbones like mammals, but unlike mammals they cannot internally (Bufo americanus americanus) and the pickerel regulate their body temperature and frog (Rana palustris). These two species exemplify are therefore called “cold-blooded” (ectothermic) animals. This means the physical, behavioral, that the animal has to move ecological and habitat to warm or cool places to change its body tempera- similarities and ture to the appropriate differences in the comfort level. Another major difference frogs and toads of between amphibians and Pennsylvania. other animals is that amphibians can breathe through the skin on photo-Andrew L. Shiels L. photo-Andrew www.fish.state.pa.us Pennsylvania Angler & Boater • March-April 2005 15 land and absorb oxygen through the weeks in some species to 60 days in (plant-eating) beginning, they have skin while underwater. Unlike reptiles, others. Frogs can become fully now developed into insectivores amphibians lack claws and nails on their developed in 60 days, but many (insect-eaters). Then they leave the toes and fingers, and they have moist, species like the green frog and bullfrog water in search of food such as small permeable and glandular skin. Their can “overwinter” as tadpoles in the insects, spiders and other inverte- skin lacks scales or feathers. bottom of ponds and take up to two brates. Frogs and toads belong to the years to transform fully into adult Where they go in search of this amphibian order Anura. -

Checklist of Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals of New York

CHECKLIST OF AMPHIBIANS, REPTILES, BIRDS AND MAMMALS OF NEW YORK STATE Including Their Legal Status Eastern Milk Snake Moose Blue-spotted Salamander Common Loon New York State Artwork by Jean Gawalt Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Fish and Wildlife Page 1 of 30 February 2019 New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Fish and Wildlife Wildlife Diversity Group 625 Broadway Albany, New York 12233-4754 This web version is based upon an original hard copy version of Checklist of the Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals of New York, Including Their Protective Status which was first published in 1985 and revised and reprinted in 1987. This version has had substantial revision in content and form. First printing - 1985 Second printing (rev.) - 1987 Third revision - 2001 Fourth revision - 2003 Fifth revision - 2005 Sixth revision - December 2005 Seventh revision - November 2006 Eighth revision - September 2007 Ninth revision - April 2010 Tenth revision – February 2019 Page 2 of 30 Introduction The following list of amphibians (34 species), reptiles (38), birds (474) and mammals (93) indicates those vertebrate species believed to be part of the fauna of New York and the present legal status of these species in New York State. Common and scientific nomenclature is as according to: Crother (2008) for amphibians and reptiles; the American Ornithologists' Union (1983 and 2009) for birds; and Wilson and Reeder (2005) for mammals. Expected occurrence in New York State is based on: Conant and Collins (1991) for amphibians and reptiles; Levine (1998) and the New York State Ornithological Association (2009) for birds; and New York State Museum records for terrestrial mammals.