Fowler's Toad (Anaxyrus Fowleri)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ballistic Protective Properties of Material Representative of English Civil War Buff-Coats and Clothing

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UWE Bristol Research Repository International Journal of Legal Medicine (2020) 134:1949–1956 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-020-02378-x ORIGINAL ARTICLE Ballistic protective properties of material representative of English civil war buff-coats and clothing Brian May1 & Richard Critchley1 & Debra Carr1,2 & Alan Peare1 & Keith Dowen3 Received: 19 March 2020 /Accepted: 15 July 2020 / Published online: 21 July 2020 # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract One type of clothing system used in the English Civil War, more common amongst cavalrymen than infantrymen, was the linen shirt, wool waistcoat and buff-coat. Ballistic testing was conducted to estimate the velocity at which 50% of 12-bore lead spherical projectiles (V50) would be expected to perforate this clothing system when mounted on gelatine (a tissue simulant used in wound ballistic studies). An estimated six-shot V50 for the clothing system was calculated as 102 m/s. The distance at which the projectile would have decelerated from the muzzle of the weapon to this velocity in free flight was triple the recognised effective range of weapons of the era suggesting that the clothing system would provide limited protection for the wearer. The estimated V50 was also compared with recorded bounce-and-roll data; this suggested that the clothing system could provide some protection to the wearer from ricochets. Finally, potential wounding behind the clothing system was investigated; the results compared favourably with seventeenth century medical writings. Keywords Leather . Linen . Wool . Behind armour blunt trauma . -

Pinjarra Park Printable Form Guide

FREE printable form guides from www.punters.com.au Pinjarra Park Tuesday 25th April 2017 Race 1 PINJARRA RSL MAIDEN 1600m 1:09 pm Race 2 SOUND TELEGRAPH HANDICAP 1500m 1:44 pm Race 3 AURORA LANDSCAPING MAIDEN 1200m 2:19 pm Race 4 PINJARRA REAL ESTATE MAIDEN 1200m 2:54 pm Race 5 WORK CLOBBER MANDURAH MAIDEN 1000m 3:29 pm Race 6 SIGN STRATEGY HANDICAP 1000m 4:04 pm Race 7 WAROONA RURAL SERVICES HANDICAP 2000m 4:34 pm Race 8 RENEW IPL HANDICAP 1300m 5:10 pm Produced for free by Punters.com.au, thanks to William Hill Punters.com.au is your ultimate racing website. Social networking, free form guides, odds comparison, betting deals, the latest news, photos and a revolutionary tipping system allowing punters to buy and sell their horse racing tips. Visit www.punters.com.au for more information. © 2017 Punters Paradise Pty Ltd. If you're reading this copyright notice you're probably thinking of printing lots of copies. Go for it. Give a copy to your mates, your mum and some strangers at the TAB. We want people to have our free form guides. Just don't sell them, alter, change or reproduce parts of this form guide as it's strictly prohibited. While Punters.com.au takes all care in the preparation of information we accept no responsibility nor warrants the accuracy of the information displayed. © 2017 Racing Australia Pty Ltd (RA) (and other parties working with it). Racing materials, including fields, form and results are subject to copyright which is owned by RA and other parties working with it. -

Veterans Park Herpetological Report Manning 2015

To Whom It May Concern, The information in this document is the summary of a series of volunteer reptile and amphibian observations conducted in Hamilton Veteran’s Park in Mercer County, NJ. The document has been prepared for the Township of Hamilton. The results presented are from field observations and data collected in 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015. The data from the first three years was taken informally during morning and evening walks with family. The data from 2015 was taken for a volunteer reptile and amphibian survey performed upon the request of the Township of Hamilton, Mercer County, NJ. This information is presented voluntarily for use in conservation endeavors. General Profile: Hamilton Veteran’s Park is a 350‐acre park managed by the Township of Hamilton in Mercer County, New Jersey. The park features a diversity of habitats within its boundaries, including a field which was the site of a former farm, a wetlands meadow, a smaller upland meadow, several patches of deciduous forest, a man‐made lake, temporary and permanent wetlands, an intermittent stream, and several permanent streams. The park is located on the physiographic province known as the inner coastal plain. Comments on General Fauna: The Veteran’s Park property provides a variety of habitats for native fauna to flourish. Healthy numbers of invertebrates have been observed during the survey. Checking under logs and other cover debris reveals a multitude of native decomposers, such as ants, earthworms, slugs, centipedes, harvestmen, and others. Ticks are occasionally seen in the fields, however most of those observed were dog ticks. -

Mitochondrial Discordance and Gene Flow in a Recent Radiation of Toads

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 59 (2011) 66–80 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Nuclear–mitochondrial discordance and gene flow in a recent radiation of toads ⇑ Brian E. Fontenot , Robert Makowsky 1, Paul T. Chippindale Department of Biology, University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, TX 76019, United States article info abstract Article history: Natural hybridization among recently diverged species has traditionally been viewed as a homogenizing Received 28 April 2010 force, but recent research has revealed a possible role for interspecific gene flow in facilitating species Revised 12 December 2010 radiations. Natural hybridization can actually contribute to radiations by introducing novel genes or Accepted 23 December 2010 reshuffling existing genetic variation among diverging species. Species that have been affected by natural Available online 19 January 2011 hybridization often demonstrate patterns of discordance between phylogenies generated using nuclear and mitochondrial markers. We used Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism (AFLP) data in conjunc- Keywords: tion with mitochondrial DNA in order to examine patterns of gene flow and nuclear–mitochondrial dis- Toads cordance in the Anaxyrus americanus group, a recent radiation of North American toads. We found high Hybridization Gene flow levels of gene flow between putative species, particularly in species pairs sharing similar male advertise- Speciation ment calls that occur in close geographic proximity, suggesting that prezygotic reproductive isolating AFLPs mechanisms and isolation by distance are the primary determinants of gene flow and genetic differenti- Nuclear–mitochondrial discordance ation among these species. Additionally, phylogenies generated using AFLP and mitochondrial data were markedly discordant, likely due to recent and/or ongoing natural hybridization events between sympatric populations. -

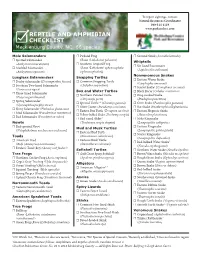

Checklist Reptile and Amphibian

To report sightings, contact: Natural Resources Coordinator 980-314-1119 www.parkandrec.com REPTILE AND AMPHIBIAN CHECKLIST Mecklenburg County, NC: 66 species Mole Salamanders ☐ Pickerel Frog ☐ Ground Skink (Scincella lateralis) ☐ Spotted Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) palustris) Whiptails (Ambystoma maculatum) ☐ Southern Leopard Frog ☐ Six-lined Racerunner ☐ Marbled Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) sphenocephala (Aspidoscelis sexlineata) (Ambystoma opacum) (sphenocephalus)) Nonvenomous Snakes Lungless Salamanders Snapping Turtles ☐ Eastern Worm Snake ☐ Dusky Salamander (Desmognathus fuscus) ☐ Common Snapping Turtle (Carphophis amoenus) ☐ Southern Two-lined Salamander (Chelydra serpentina) ☐ Scarlet Snake1 (Cemophora coccinea) (Eurycea cirrigera) Box and Water Turtles ☐ Black Racer (Coluber constrictor) ☐ Three-lined Salamander ☐ Northern Painted Turtle ☐ Ring-necked Snake (Eurycea guttolineata) (Chrysemys picta) (Diadophis punctatus) ☐ Spring Salamander ☐ Spotted Turtle2, 6 (Clemmys guttata) ☐ Corn Snake (Pantherophis guttatus) (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus) ☐ River Cooter (Pseudemys concinna) ☐ Rat Snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) ☐ Slimy Salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) ☐ Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) ☐ Eastern Hognose Snake ☐ Mud Salamander (Pseudotriton montanus) ☐ Yellow-bellied Slider (Trachemys scripta) (Heterodon platirhinos) ☐ Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber) ☐ Red-eared Slider3 ☐ Mole Kingsnake Newts (Trachemys scripta elegans) (Lampropeltis calligaster) ☐ Red-spotted Newt Mud and Musk Turtles ☐ Eastern Kingsnake -

Bear Facts: the History and Folklore of Island Bears Part Two

Folklore Bear Facts: The History and Folklore of Island Bears Part Two A handmade wooden toy pits man (?) against bear — too often the case on Prince by Jim Hornby Edward Island. In Part One of "Bear Facts/' which groups for protection against bears. An none have been seen . and it was featured in Issue 22 (Fall-Winter, 1836 visitor to Morell stated, "Bears was generally believed that they 1987), Jim Hornby treated readers to a are said to be frequently seen in this had disappeared entirely. history of the black bear on Prince neighbourhood." In 1862, the Guardian Edward Island. In the conclusion to his recorded that "Bears are becoming very The actual shooting had occurred on study, Hornby chronicles the passing numerous and exceedingly troublesome February 7, 1927. The late Bernard of Ursus americanus in the province, east of Souris." Even near the turn of Leslie of Souris Line Road was 16 when and examines its long afterlife in the century, bears were reported only he and his 18-year-old brother, George, Island folklore. as "gradually becoming scarcer" in the hunted and killed the bear. George Dundas area. noticed the tracks where the bear had The extinction of the bear on Prince crossed the north end of Souris Line Forgotten But N o t Gon e Edward Island was explained, a bit Road, heading east by Hainey's Brook. prematurely, by a commentator in 1900: Bernard told me the story. "A thaw espite their large size (even the "The forests have fallen before the came, a February thaw, and the bear Dvolume of their breath could give woodsman's axe. -

Top 10 Birds for Raising Backyard Chickens

Top 10 Birds for Raising Backyard Chickens (According to Chickenreview.com) When you’re picking your first flock, there are a few key things to look for: 1. The breed should be a recognized breed, and should be easy to find in most hatcheries. 2. The breed should have a reputation for docility, friendliness, and general tameness. 3. The breed should be fairly low-maintenance without too many care issues. You should decide whether you’re raising chickens for table meat or just eggs. If you want eggs, choose a breed that excels at laying. If you want meat, make sure to pick birds that gain weight quickly. The great thing about chickens is there are a few breeds that meet these criteria, making them excellent birds for the average backyard flock. Some of these birds are good layers and some are good layers and meat birds also! We’ve put together a list of our ten favorite chicken breeds for Urban or backyard flocks. Each of the breeds on our list meets most of the items to look for we’ve mentioned, and are very good birds for a beginner. 1: Rhode Island Red: The Best Dual-Purpose Bird: Easy to care for and a good layer! They are a popular choice for backyard flocks because of their egg laying abilities and hardiness. Although they can sometimes be stubborn, healthy hens can lay up to 5–6 eggs per week depending on their care and treatment. Rhode Island Red hens lay many more eggs than an average hen if provided plenty of quality feed 2: Buff Orpington: The Best Pet Chicken: The one caution on this breed is that their docile nature will often make them a target for bullying from other birds. -

American Toad (Anaxyrus Americanus) Fowler's Toad (Anaxyrus Fowleri

Vermont has eleven known breeding species of frogs. Their exact distributions are still being determined. In order for these species to survive and flourish, they need our help. One way you can help is to report the frogs that you come across in the state. Include in your report as much detail as you can on the appearance and location of the animal; also include the date of the sighting, your name, and how to contact you. Photographs are ideal, but not necessary. When attempting to identify a particular species, check at least three different field markings so that you can be sure of what it is. To contribute a report, you may use our website (www.vtherpatlas.org) or contact Jim Andrews directly at [email protected]. American Bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) American Toad (Anaxyrus americanus) The American Bullfrog is our largest frog and can reach 7 inches long. The Bullfrog is one of the three The American Toad is one of Vermont’s two toad species. Toads can be distinguished from other green-faced frogs in Vermont. It has a green and brown mottled body with dark stripes across its legs. frogs in Vermont by their dry and bumpy skin, and the long oval parotoid glands on each side of their The Bullfrog does not have dorsolateral ridges, but it does have a ridge that starts at the eye and goes necks. The American Toad has at least one large wart in each of the large black spots found along its around the eardrum (tympana) and down. The Bullfrog’s call is a deep low jum-a-rum. -

Classic Animaeon Teaching Resource

Classic Anima+on Teaching Resource This resource includes: About Educational • 7 very short animated films that use simple Resource storytelling techniques This • Step-by-step lesson plans on storytelling • Genres and interpretaon Pack • Learning to listen and retell stories creavely • Think creavely about animang your Key learning objec+ves: own stories • Some simple historical facts on animaon and Research has shown that children learn more games to start to think about global quickly through oral storytelling: their reading geography and wri7ng skills develop more quickly. • Accompanying resources and ac7vi7es for each lesson This pack is intended to educate students • Comprehensive fact sheets on all topics about Africa and a sense of place; about covered family-7es and the role of storytelling in educaon in Africa; and about animaon. It will smulate imaginaon and creave This pack is divided into three dis7nct parts. First thinking, it will encourage children to think it includes 3 detailed lesson outlines. These about the similari7es and the differences contain 7ps and advice on how to teach certain between children living in the UK and in Africa, aspects that are relevant to the films under enhance cultural awareness, and improve discussion but could also be taught listening skills through storytelling. Teachers independently of the films. Then there is a are also encouraged to incorporate some sec7on with Teacher Resources. This contains language learning into their exploraon of fact and informaon sheets as well as more African animaon, using the ‘Passeport pour la background on the topics under discussion, and francophonie’ on the SCILT website: tools designed to teach some complex topics. -

Griffintayle-Aug-2003

*5,)),T7"=/( Newsletter of the Barony of Politarchopolis August AS38 “Fraudem! Fraudem! Mea pecunia vobis redenda est!” Griffintayle is published by and for the Barony of Politarchopolis. It is not a corporate publication of the Society for Creative Anachronism and does not delineate SCA policy. Griffintayle is produced by Anwyn Davies Griffintayle has a limited free distribution. Secure your postal copy by subscription - $8.00 per year. Baronial Homepage: http://www.sca.org.au/politarchopolis/ Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 10 11 12 13 14 15 Booking price for 16 Guild Day, St. O ~o dPO Crusade, Borderscros, Florians goes up today A 17 18 19 20 21 22 Benevolence 23 Benevolence U O ~o dO Crusade, Borderscros Crusade, Borderscros G 24 Benevolence 25 26 27 28 29 30 Games and Crusade, Borderscros Potluck dPO O ~o 31 Heraldic Tourney 1 2 3 4 5 6 ~ ;O S 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 E O ~o dPO P 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 O ~o dO 21 Heavy Quest at 22 23 24 25 26 27 Feast of the Redwood Grove dPO Butterflies ~o REGULAR MEETINGS ;Baronial Meetings: the first Wednesday of the month at 7:30 pm. Next Meeting will be at ANU, Copland G030 O Baronial heavy fighter practice: - Sunday: from 3:00 pm at Haig Park, O’Connor near scout hall, Fencers and heavies welcome. This is not an SCA event, as waivers are not collected. - Wednesday evenings: from 6:30 pm, at Mawson Oval. This is not an SCA event, as waivers are not collected. -

Species Status Assessment Report for the Eastern Population of The

Species Status Assessment Report for the Eastern Population of the Boreal Toad, Anaxyrus boreas boreas Prepared by the Western Colorado Ecological Services Field Office U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Grand Junction, Colorado EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This species status assessment (SSA) reports the results of the comprehensive biological status review by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) for the Eastern Population of the boreal toad (Anaxyrus boreas boreas) and provides a thorough account of the species’ overall viability and, therefore, extinction risk. The boreal toad is a subspecies of the western toad (Anaxyrus boreas, formerly Bufo boreas). The Eastern Population of the boreal toad occurs in southeastern Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, northern New Mexico, and most of Utah. This SSA Report is intended to provide the best available biological information to inform a 12-month finding and decision on whether or not the Eastern Population of boreal toad is warranted for listing under the Endangered Species Act (Act), and if so, whether and where to propose designating critical habitat. To evaluate the biological status of the boreal toad both currently and into the future, we assessed a range of conditions to allow us to consider the species’ resiliency, redundancy, and representation (together, the 3Rs). The boreal toad needs multiple resilient populations widely distributed across its range to maintain its persistence into the future and to avoid extinction. A number of factors influence whether boreal toad populations are considered resilient to stochastic events. These factors include (1) sufficient population size (abundance), (2) recruitment of toads into the population, as evidenced by the presence of all life stages at some point during the year, and (3) connectivity between breeding populations. -

Saving the Mountain Chicken

Saving the mountain chicken Long-Term Recovery Strategy for the Critically Endangered mountain chicken 2014-2034 Adams, S L, Morton, M N, Terry, A, Young, R P, Dawson, J, Martin, L, Sulton, M, Hudson, M, Cunningham, A, Garcia, G, Goetz, M, Lopez, J, Tapley, B, Burton, M and Gray, G. Front cover photograph Male mountain chicken. Matthew Morton / Durrell (2012) Back cover photograph Credits All photographs in this plan are the copyright of the people credited; they must not be reproduced without prior permission. Recommended citation Adams, S L, Morton, M N, Terry, A, Young, R P, Dawson, J, Martin, L, Sulton, M, Cunningham, A, Garcia, G, Goetz, M, Lopez, J, Tapley, B, Burton, M, and Gray, G. (2014). Long-Term Recovery Strategy for the Critically Endangered mountain chicken 2014-2034. Mountain Chicken Recovery Programme. New Information To provide new information to update this Action Plan, or correct any errors, e-mail: Jeff Dawson, Amphibian Programme Coordinator, Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, [email protected] Gerard Gray, Director, Department of Environment, Ministry of Agriculture, Land, Housing and Environment, Government of Montserrat. [email protected] i Saving the mountain chicken A Long-Term Recovery Strategy for the Critically Endangered mountain chicken 2014-2034 Mountain Chicken Recovery Programme ii Forewords There are many mysteries about life and survival on Much and varied research and work needs continue however Montserrat for animals, plants and amphibians. In every case before our rescue mission is achieved. The chytrid fungus survival has been a common thread in the challenges to life remains on Montserrat and currently there is no known cure.