World Heritage in Iran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Welcoming Roles of Iranian Traditional Buildings Entrances

J. Appl. Environ. Biol. Sci. , 5(4)184-189, 2015 ISSN: 2090-4274 Journal of Applied Environmental © 2015, TextRoad Publication and Biological Sciences www.textroad.com The Welcoming Roles of Iranian Traditional Buildings Entrances Ahad Nejad Ebrahimi 1, Mohammad Taghi Pirbabaei2, Fahimeh Shahiri Mehrabad 3 1Assistant professor, Architecture and Urbanism Faculty, Tabriz Islamic Art University, Iran 2Associate Professor, Architecture and Urbanism Faculty, Tabriz Islamic Art University, Iran 3Master Student in Islamic Architecture, Architecture and Urbanism Faculty, Tabriz Islamic Art University, Iran Received: September 16, 2014 Accepted: February 26, 2015 ABSTRACT Salutation and Greeting at the beginning of visiting has a significant role in Iranian culture. After the advent of Islam which was emphasizing respect to guests in Quran verses and Hadith, equality and fraternity notions were added to the culture which leads to changes in Islamic urban framework. Despite the simplicity of walls and the similarity among houses which show equality between the rich and the poor, the connection point of houses to public passages, was a place for owner greetings and expressing fraternity to the pedestrians and guests who intended to enter the house. In this study, 21 traditional houses in traditional context and 58 contemporary dwellings (apartments and houses with yards) were investigated based on explanatory descriptive method in 3 cities of Iran. Furthermore, hidden religious concepts in greeting (invitation, welcoming, permission and acceptance) were evaluated and their manifestation in traditional Iranian framework (Safavid and Qajar period) in cultural domestic setting was also studied. Finally, continuation or absence of these concepts at the moment of entering the privacy of present houses will be discussed. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Dr. Rahim Heydari Chianeh (PhD) Department of Geography and Urban Planning, Faculty of Geography and Planning P.Box 23 29 Bahman Av., University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran Fax: + 98 411 333 56 013 Phone: 333 62 330 (Home) 333 92 298 (Office) Mob.: 09144194700 Email: [email protected] Kimlik no 2909074277 Personal Data: Name Surname Date of Birth Nationality Sex Marital Status RAHIM HEYDARI-CHIANEH 1974/4/22 IRAN M Mar. Telephone Fax E-mail +98 41 33 36 23 30 +98 41 33 35 60 13 [email protected] Educational Background: Certificate Degree Field of Specialization Name of Institution Attended Date Received URBAN UNIVERSITY OF TABRIZ, IRAN 1999 M. A. PLANNING AND GEOGRAPHY URBAN UNIVERSITY OF TABRIZ, IRAN 2004 Ph.D PLANNING AND GEOGRAPHY Title of Doctorate Thesis: AN EVALUATION OF IRANIAN TOURISM INDUSTRY PLANNING Title of Post-Graduate Thesis: ROLE OF GREEN SPACES IN URBAN PLANNING CASE STUDY: TABRIZ METROPOLIS 1 Teaching Experiences: Over than 25 Course in B.A, M.A., and PhD degrees from 1999 up to now, some of them are in the table below: Dates Title of Course Level Name of Institution From To Urban Tourim Ph.D 2009 Up Dept. of Geography and Urban to Planning, University of Tabriz now Tourism Marketing B.A 2001 - Dept. of Tourism Management, University of Tabriz Tourism Geography B.A 2000 - Dept. of Geography and Urban Planning, University of Tabriz Urban Geography “ “ - “ Philisophy of Geography “ 2002 - “ Reginal Planning M.A 2007 - “ Population Geography ,, 2003 - “ Demography ,, 2003 - “ Urban Development ,, 2002 - “ Tourism Geography M.A 2007 - “ Tourism in Iran 2001 2009 ITTO Philisophy of Geography M.A 2010 - Aras International Campus University of Tabriz Population Geography M.A 2010 2014 “ Analysis Ecotourism Planning M.A 2011 - Dept. -

Open Letter to His Excellency, Ayatollah Ali Hosseini Khamenei, Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran

1 His Excellency Ayatollah Ali Hosseini Khamenei Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran The Office of the Supreme Leader Tehran Province, Tehran, District 11, Islamic Republic of Iran 17 February 2021 Joint open letter to His Excellency, Ayatollah Ali Hosseini Khamenei, Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran Your Excellency, We, the undersigned, write to you to express our grave concern over the arbitrary imprisonment of Dr Reza Eslami in Tehran’s Evin Prison. Dr Eslami’s case is illustrative of the ongoing clampdown against the legal and academic professions in Iran. On Monday 15 February 2021, 58 countries launched the International Declaration Against Arbitrary Detention in State-to-State Relations1, characterizing such arbitrary detention as a standing violation of international law. The case against Dr Eslami is an emblematic assault on this rules-based international order. On 7 February 2021,2 Dr Reza Eslami, an Iranian-Canadian human rights and environmental law professor at Beheshti University,3 was sentenced to seven years imprisonment by Branch 15 of the Revolutionary Court after being charged with ‘cooperating with a hostile state.’4 The case against Dr Eslami is devoid of any credible evidence and derives from spurious charges to begin with. We believe that this case is based on his participation in a training course on the rule of law in the Czech Republic in 2020, funded by a United States-based non-government organisation (NGO). Dr Eslami has refuted the charges as baseless, stating that his academic work was free of ‘political, security and foreign- relations issues’5 . -

Redalyc.Checklist of the Genus Eugnorisma Boursin, 1946 of Iran with New Records and Distributional Data (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae

SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología ISSN: 0300-5267 [email protected] Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología España Rabieh, M. M.; Seraj, A. A.; Gyulai, P.; Esfandiari, M. Checklist of the genus Eugnorisma Boursin, 1946 of Iran with new records and distributional data (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae, Noctuinae) SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología, vol. 41, núm. 163, septiembre, 2013, pp. 399-413 Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45529269018 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative 399-413 Checklist of the Eugno 4/9/13 12:16 Página 399 SHILAP Revta. lepid., 41 (163), septiembre 2013: 399-413 eISSN: 2340-4078 ISSN: 0300-5267 Checklist of the genus Eugnorisma Boursin, 1946 of Iran with new records and distributional data (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae, Noctuinae) M. M. Rabieh, A. A. Seraj, P. Gyulai & M. Esfandiari Abstract A checklist of 9 species and 4 subspecies of the genus Eugnorisma Boursin, 1946, in Iran, with remarks, is presented based on the literature and our research results. Furthermore 1 species and 4 subspecies are discussed, as formerly erroneously published taxons from Iran, because of misidentification or mislabeling. Two further subspecies, E. insignata leuconeura (Hampson, 1918) and E. insignata pallescens Christoph, 1893, formerly treated as valid taxons, are downgraded to mere form, both of them occurring in Iran. New data on the distribution of some species of this genus in Iran are also given. -

WAIPA-Annual-Report-2004.Pdf

Note The WAIPA Annual Report 2004 has been produced by WAIPA, in cooperation with the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). This report was prepared by Vladimir Pankov. Beatrice Abel provided editorial assistance. Teresita Sabico and Farida Negreche provided assistance in formatting the report. WAIPA would like to thank all those who have been involved in the preparation of this report for their various contributions. For further information on WAIPA, please contact the WAIPA Secretariat at the following address: WAIPA Secretariat Palais des Nations, Room E-10061 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (41-22) 907 46 43 Fax: (41-22) 907 01 97 Homepage: http://www.waipa.org UNCTAD/ITE/IPC/2005/3 Copyright @ United Nations, 2005 All rights reserved 2 Table of Contents Page Note 2 Table of Contents 3 Acknowledgements 4 Facts about WAIPA 5 WAIPA Map 8 Letter from the President 9 Message from UNCTAD 10 Message from FIAS 11 Overview of Activities 13 The Study Tour Programme 24 WAIPA Elected Office Bearers 25 WAIPA Consultative Committee 27 List of Participants: WAIPA Executive Meeting, Ninth Annual WAIPA Conference and WAIPA Training Workshops 29 Statement of Income and Expenses - 2004 51 WAIPA Directory 55 ANNEX: WAIPA Statute 101 3 Acknowledgements WAIPA would like to thank Ernst & Young – International Location Advisory Services (E&Y–ILAS); IBM Business Consulting Services – Plant Location International (IBM Business Consulting Services – PLI); and OCO Consulting for contributing their time and expertise to the WAIPA Training Programme. Ernst & Young – ILAS IBM Business Consulting Services – PLI OCO Consulting 4 Facts about WAIPA What is WAIPA? The World Association of Investment Promotion Agencies (WAIPA) was established in 1995 and is registered as a non-governmental organization (NGO) in Geneva, Switzerland. -

Persian Heritage: a Significant Role in Achieving Sustainable Development

International Journal of Cultural Heritage E. Abedi, D. Kralj http://iaras.org/iaras/journals/ijch Persian heritage: A Significant Role in Achieving Sustainable Development ELAHEH ABEDI1, DAVORIN KRALJ2, A.M.Co., Tehran, IRAN1 ALMA MATER EUROPAEA, Slovenska 17, 2000 Maribor, SLOVENIA2, [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: In every country, heritage plays a significant role in achieving sustainable development. Iran, a high plateau located at latitudes in the range of 25-40 in an arid zone in the northern hemisphere of the East, is a vast country with different climatic zones. In the past, traditional builders have presented several logical climatic solutions in order to enhance human comfort. In fact, this emphasis has been one of the most important and fundamental features of Iranian architecture. To a significant extent, Iranian architecture has been based on climate, geography, available materials, and cultural beliefs. Therefore, traditional Iranian builders had to devise various techniques to enhance architectural sustainability through the use of natural materials, and they had to do so in the absence of modern technologies. Paper describes the principals and methods of vernacular architectural designs in Iran with given examples which is predominately focused on some eclectic ancient cities in Iran as Kashan, Isfahan, and Yazd. Design and technological considerations of past, such as sustainable performance of natural materials, optimum usage of available materials, and the use of wind and solar power, were studied in order to provide effective eco architectural designs to provide the architectural criteria and insights. This study will be beneficial to today architects in the design of architectural structures to provide human comfort and a sustainable life in adverse climatic conditions. -

Iran's Nuclear Ambitions From

IDENTITY AND LEGITIMACY: IRAN’S NUCLEAR AMBITIONS FROM NON- TRADITIONAL PERSPECTIVES Pupak Mohebali Doctor of Philosophy University of York Politics June 2017 Abstract This thesis examines the impact of Iranian elites’ conceptions of national identity on decisions affecting Iran's nuclear programme and the P5+1 nuclear negotiations. “Why has the development of an indigenous nuclear fuel cycle been portrayed as a unifying symbol of national identity in Iran, especially since 2002 following the revelation of clandestine nuclear activities”? This is the key research question that explores the Iranian political elites’ perspectives on nuclear policy actions. My main empirical data is elite interviews. Another valuable source of empirical data is a discourse analysis of Iranian leaders’ statements on various aspects of the nuclear programme. The major focus of the thesis is how the discourses of Iranian national identity have been influential in nuclear decision-making among the national elites. In this thesis, I examine Iranian national identity components, including Persian nationalism, Shia Islamic identity, Islamic Revolutionary ideology, and modernity and technological advancement. Traditional rationalist IR approaches, such as realism fail to explain how effective national identity is in the context of foreign policy decision-making. I thus discuss the connection between national identity, prestige and bargaining leverage using a social constructivist approach. According to constructivism, states’ cultures and identities are not established realities, but the outcomes of historical and social processes. The Iranian nuclear programme has a symbolic nature that mingles with socially constructed values. There is the need to look at Iran’s nuclear intentions not necessarily through the lens of a nuclear weapons programme, but rather through the regime’s overall nuclear aspirations. -

Zeinab Jalalian V. Iran Submission to WGAD, March 2015

Zeinab Jalalian v. Iran Submission to WGAD, March 2015 Contents I. Identity of the Complainant ..................................................................................................................... 2 II. Introduction and Summary ..................................................................................................................... 3 III. Statement of Facts .................................................................................................................................. 6 Background .............................................................................................................................................. 6 10 March 2008: Arrest and detention of Ms. Jalalian in Iran .................................................................. 7 10 March 2008 – December 2008: Kermanshah Intelligence Prison and Kermanshah Juvenile Correction and Training Centre ............................................................................................................... 7 3 December 2008: Ms. Jalalian’s trial and conviction ............................................................................. 9 Lack of access to health care ................................................................................................................. 16 IV. VIOLATIONS .......................................................................................................................................... 17 Category I: No justification for the deprivation of liberty .................................................................... -

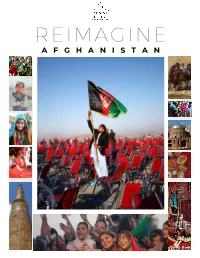

Reimagine a F G H a N I S T a N

REIMAGINE A F G H A N I S T A N A N I N I T I A T I V E B Y R A I S I N A H O U S E REIMAGINE A F G H A N I S T A N INTRODUCTION . Afghanistan equals Culture, heritage, music, poet, spirituality, food & so much more. The country had witnessed continuous violence for more than 4 ................................................... decades & this has in turn overshadowed the rich cultural heritage possessed by the country, which has evolved through mellinnias of Cultural interaction & evolution. Reimagine Afghanistan as a digital magazine is an attempt by Raisina House to explore & portray that hidden side of Afghanistan, one that is almost always overlooked by the mainstream media, the side that is Humane. Afghanistan is rich in Cultural Heritage that has seen mellinnias of construction & destruction but has managed to evolve to the better through the ages. Issued as part of our vision project "Rejuvenate Afghanistan", the magazine is an attempt to change the existing perception of Afghanistan as a Country & a society bringing forward that there is more to the Country than meets the eye. So do join us in this journey to explore the People, lifestyle, Art, Food, Music of this Adventure called Afghanistan. C O N T E N T S P A G E 1 AFGHANISTAN COUNTRY PROFILE P A G E 2 - 4 PEOPLE ETHNICITY & LANGUAGE OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 5 - 7 ART OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 8 ARTISTS OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 9 WOOD CARVING IN AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 0 GLASS BLOWING IN AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 1 CARPETS OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 2 CERAMIC WARE OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 3 - 1 4 FAMOUS RECIPES OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 5 AFGHANI POETRY P A G E 1 6 ARCHITECTURE OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 7 REIMAGINING AFGHANISTAN THROUGH CINEMA P A G E 1 8 AFGHANI MOVIE RECOMMENDATION A B O U T A F G H A N I S T A N Afghanistan Country Profile: The Islamic Republic of Afghanistan is a landlocked country situated between the crossroads of Western, Central, and Southern Asia and is at the heart of the continent. -

Ancient Egyptian Chronology.Pdf

Ancient Egyptian Chronology HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST Ancient Near East Editor-in-Chief W. H. van Soldt Editors G. Beckman • C. Leitz • B. A. Levine P. Michalowski • P. Miglus Middle East R. S. O’Fahey • C. H. M. Versteegh VOLUME EIGHTY-THREE Ancient Egyptian Chronology Edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2006 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ancient Egyptian chronology / edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton; with the assistance of Marianne Eaton-Krauss. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, The Near and Middle East ; v. 83) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-90-04-11385-5 ISBN-10: 90-04-11385-1 1. Egypt—History—To 332 B.C.—Chronology. 2. Chronology, Egyptian. 3. Egypt—Antiquities. I. Hornung, Erik. II. Krauss, Rolf. III. Warburton, David. IV. Eaton-Krauss, Marianne. DT83.A6564 2006 932.002'02—dc22 2006049915 ISSN 0169-9423 ISBN-10 90 04 11385 1 ISBN-13 978 90 04 11385 5 © Copyright 2006 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

KHERAD-DISSERTATION-2013.Pdf

Copyright by Nastaran Narges Kherad 2013 The Dissertation Committee for Nastaran Narges Kherad Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: RE-EXAMINING THE WORKS OF AHMAD MAHMUD: A FICTIONAL DEPICTION OF THE IRANIAN NATION IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE 20TH CENTURY Committee: M.R. Ghanoonparvar, Supervisor Kamran Aghaie Kristen Brustad Elizabeth Richmond-Garza Faegheh Shirazi RE-EXAMINING THE WORKS OF AHMAD MAHMUD: A FICTIONAL DEPICTION OF THE IRANIAN NATION IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE 20TH CENTURY by Nastaran Narges Kherad, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2013 Dedication Dedicated to my son, Manai Kherad-Aminpour, the joy of my life. May you grow with a passion for literature and poetry! And may you face life with an adventurous spirit and understanding of the diversity and complexity of humankind! Acknowledgements The completion of this dissertation could not have been possible without the ongoing support of my committee members. First and for most, I am grateful to Professor Ghanoonparvar, who believed in this project from the very beginning and encouraged me at every step of the way. I thank him for giving his time so generously whenever I needed and for reading, editing, and commenting on this dissertation, and also for sharing his tremendous knowledge of Persian literature. I am thankful to have the pleasure of knowing and working with Professor Kamaran Aghaei, whose seminars on religion I cherished the most. -

See the Document

IN THE NAME OF GOD IRAN NAMA RAILWAY TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN List of Content Preamble ....................................................................... 6 History ............................................................................. 7 Tehran Station ................................................................ 8 Tehran - Mashhad Route .............................................. 12 IRAN NRAILWAYAMA TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN Tehran - Jolfa Route ..................................................... 32 Collection and Edition: Public Relations (RAI) Tourism Content Collection: Abdollah Abbaszadeh Design and Graphics: Reza Hozzar Moghaddam Photos: Siamak Iman Pour, Benyamin Tehran - Bandarabbas Route 48 Khodadadi, Hatef Homaei, Saeed Mahmoodi Aznaveh, javad Najaf ...................................... Alizadeh, Caspian Makak, Ocean Zakarian, Davood Vakilzadeh, Arash Simaei, Abbas Jafari, Mohammadreza Baharnaz, Homayoun Amir yeganeh, Kianush Jafari Producer: Public Relations (RAI) Tehran - Goragn Route 64 Translation: Seyed Ebrahim Fazli Zenooz - ................................................ International Affairs Bureau (RAI) Address: Public Relations, Central Building of Railways, Africa Blvd., Argentina Sq., Tehran- Iran. www.rai.ir Tehran - Shiraz Route................................................... 80 First Edition January 2016 All rights reserved. Tehran - Khorramshahr Route .................................... 96 Tehran - Kerman Route .............................................114 Islamic Republic of Iran The Railways