Trabajo Fin De Grado

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wendy A. Woloson. Refined Tastes: Sugar, Confectionery, and Consumers in Nineteenth‐Century America

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons College of the Pacific aF culty Articles All Faculty Scholarship Spring 1-1-2003 Wendy A. Woloson. Refined aT stes: Sugar, Confectionery, and Consumers in Nineteenth‐Century America Ken Albala University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facarticles Part of the Food Security Commons, History Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Albala, K. (2003). Wendy A. Woloson. Refined Tastes: Sugar, Confectionery, and Consumers in Nineteenth‐Century America. Winterthur Portfolio, 38(1), 72–76. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facarticles/70 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the All Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of the Pacific aF culty Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 72 Winterthur Portfolio 38:1 upon American material life, the articles pri- ture, anthropologists, and sociologists as well as marily address objects and individuals within the food historians. It also serves as a vivid account Delaware River valley. Philadelphia, New Jersey, of the emergence of consumer culture in gen- and Delaware are treated extensively. Outlying eral, focusing on the democratization of once- Quaker communities, such as those in New En- expensive sweets due to new technologies and in- gland, North Carolina, and New York state, are es- dustrial production and their shift from symbols sentially absent from the study. Similarly, the vol- of power and status to indulgent ephemera best ume focuses overwhelmingly upon the material life left to women and children. -

A Confectionery Map of Regional Specialties

The Great North American Road Trip THE 2021 PETER’S® CHOCOLATE CALENDAR A Confectionery Map of Regional Specialties One of the great pleasures of domestic travel in North America is to see, hear and taste the regional differences that characterize us. The places where we live help shape the way we think, the way we talk and even the way we eat. So, while chocolate has always been one of the world’s great passions, the ways in which we indulge that passion vary widely from region to region. In this, our 2021 Peter’s Chocolate Calendar, we’re celebrating the great love affair between North Americans and chocolate in all its different shapes, sizes, and flavors. We hope you’ll join us on this journey and feel inspired to recreate some of the specialties we’ve collected along the way. Whether it’s catfish or country-fried steak, boiled crawfish or peach cobbler, Alabama cuisine is simply divine. Classic southern recipes are as highly prized as family heirlooms and passed down through the generations in the Cotton State. This is doubtless how the confection known as Southern Divinity built its longstanding legacy in this region. The balanced combination of salty and sweet is both heavenly and distinctly Southern. Southern Divinity Southern Divinity Sun Mon Tue Wed Thur Fri Sat Ingredients: December February 1 001 2 002 2 Egg Whites S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 17 oz Sugar 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 56 6 oz Light Corn Syrup 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 4 oz Water 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 1 tbsp Vanilla Extract 27 28 29 30 31 28 New Year’s Day 6 oz Coarsely Chopped Pecans, roasted & salted Peter’s® Marbella™ Bittersweet Chocolate, 003 004 005 006 007 008 009 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 for drizzling Directions: Beat egg whites in a stand mixer until stiff National Chocolate peaks form. -

De Top Van Beste Eetervaringen Ter Wereld

LONELY PLANET ULTIEME CULIBESTEMMINGEN ULTIEME WAAR VIND JE DE MEEST ULTIEME CULINAIRE ERVARINGEN TER WERELD? AAN DE TASMAANSE KUST WAAR JE HEERLIJK OESTERS KUNT SLURPEN? ZET JE IN TEXAS JE TANDEN IN ZACHTGEGAARDE RUNDERBORSTSTUK? GA JE JE TE BUITEN AAN PITTIGE KIP PIRI PIRI IN MOZAMBIQUE? OF BEZOEK JE NAPELS VOOR DE BESTE PIZZA MARGHERITA? WE VROEGEN HET AAN TOPCHEFS, CULINAIR JOURNALISTEN EN ULTIEME ONZE EIGEN FOODBELUSTE EXPERTS. EN DIT IS HET RESULTAAT. LONELY PLANETS NIET TE MISSEN, ABSOLUTE TOP 500 VAN BÉSTE EETERVARINGEN TER WERELD. KIJK, GENIET EN GA PROEVEN! CULIBESTEMMINGEN ISBN 9789021570679 NUR 500/440 9 789021 570679 KOSMOS UITGEVERS WWW.KOSMOSUITGEVERS.NL UTRECHT/ANTWERPEN DE TOP VAN BESTE EETERVARINGEN TER WERELD Inleiding Met moeite baan je je een weg naar de bar en zodra je de kans krijgt bestel je: ‘Un pincho de anchoas con pimientos, por favor. Y una copa de chacolí. ¡Gracias!’ Algauw verschijnt er een bordje met je eerste pintxo en een glas sprankelende Baskische wijn. ¡Salud! Welkom in San Sebastián in Spanje, een van de mooiste wereldsteden, die absoluut een culinaire verkenning verdient. De oude stad van San Sebastián ligt tussen de Bahía de le Concha en de rivier die door de stad stroomt. Overal in de nauwe straatjes zie je pintxo- bars die elk hun eigen specialiteit van deze Baskische hapjes serveren. In Bar Txepetxa aan C/Pescadería is ansjovis een vast onderdeel. Een paar deuren verder in Nestor krijg je vleestomaten salade met enkel wat olijfolie en zout, of tortilla; deze snack is zo populair dat je bij je bestelling je naam moet opgeven. -

RE-ORIENTING CUISINE Food, Nutrition, and Culture

RE-ORIENTING CUISINE Food, Nutrition, and Culture Series Editors: Rachel Black, Boston University Leslie Carlin, University of Toronto Published by Berghahn Books in Association with the Society for the Anthropology of Food and Nutrition (SAFN). While eating is a biological necessity, the production, distribution, preparation, and consumption of food are all deeply culturally inscribed activities. Taking an anthropological perspective, this book series provides a forum for thought-pro- voking work on the bio-cultural, cultural, and social aspects of human nutrition and food habits. Th e books in this series bring timely food-related scholarship to the graduate and upper-division undergraduate classroom, to a research- focused academic audience, and to those involved in food policy. Volume 1 GREEK WHISKY Th e Localization of a Global Commodity Tryfon Bampilis Volume 2 RECONSTRUCTING OBESITY Th e Meaning of Measures and the Measure of Meanings Edited by Megan McCullough and Jessica Hardin Volume 3 REORIENTING CUISINE East Asian Foodways in the Twenty-First Century Edited by Kwang Ok Kim Volume 4 FROM VIRTUE TO VICE Negotiating Anorexia Richard A. O’Connor and Penny Van Esterik Re-Orienting Cuisine East Asian Foodways in the Twenty-First Century Edited by Kwang Ok Kim berghahn N E W Y O R K • O X F O R D www.berghahnbooks.com Published by Berghahn Books www.berghahnbooks.com © 2015 Kwang Ok Kim All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission of the publisher. -

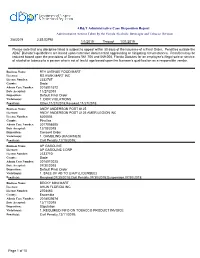

AB&T Administrative Case Disposition Report by Date

AB&T Administrative Case Disposition Report Administrative Actions Taken by the Florida Alcoholic Beverages and Tobacco Division 2/8/2019 2:35:52PM 1/1/2019 Through 1/31/2019 Please note that any discipline listed is subject to appeal within 30 days of the issuance of a Final Order. Penalties outside the AB&T Division's guildelines are based upon extensive documented aggravating or mitigating circumstances. Penalties may be reduced based upon the provisions of Sections 561.706 and 569.008, Florida Statutes for an employee's illegal sale or service of alcohol or tobacco to a person who is not of lawful age based upon the licensee's qualification as a responsible vendor. Business Name: 9TH AVENUE FOOD MART Licensee: RS KWIK MART INC License Number: 2332787 County: Dade Admin Case Number: 2018011572 Date Accepted: 11/27/2018 Disposition: Default Final Order Violation(s): 1. DOR VIOLATIONS Penalty(s): Other,11/27/2018;Revoked,11/27/2018; Business Name: ANDY ANDERSON POST #125 Licensee: ANDY ANDERSON POST #125 AMER LEGION INC License Number: 6200504 County: Pinellas Admin Case Number: 2017056505 Date Accepted: 12/18/2018 Disposition: Consent Order Violation(s): 1. GAMBLING (MACHINES) Penalty(s): Civil Penalty,12/18/2018; Business Name: AP GASOLINE Licensee: AP GASOLINE CORP License Number: 2333710 County: Dade Admin Case Number: 2018012025 Date Accepted: 07/30/2018 Disposition: Default Final Order Violation(s): 1. SALE OF AB TO U/A/P (LICENSEE) Penalty(s): Revoked,07/30/2018;Civil Penalty,07/30/2018;Suspension,07/30/2018; Business Name: BECKY MINI MART Licensee: AHUN FLORIDA INC License Number: 2704463 County: Escambia Admin Case Number: 2018039574 Date Accepted: 12/11/2018 Disposition: Stipulation Violation(s): 1. -

Malnutrition in West Africa

Brady Jeffery, Student Participant Hill City High School, Iowa Malnutrition in West Africa In the West African nations of Niger, Mauritania, Senegal, Gambia, Cape Verde and Mali over half a million people are affected by drought. The ones starving are the poor and unemployed. In January a huge storm killed tens of thousands of livestock on which almost everybody depends on for making it through the hungry season. Then in July, late, low rainfall postponed the start of the cropping season and even eliminated it in some areas. Still suffering from a bad harvest in 2001, the natural disasters have emptied the grain reserves and required families to leave out meals to cope with the food shortages. Many people are forced to borrow money to pay for food that they can find in local markets. The 2002 harvest was 23% less than the previous years. A recent food evaluation showed that many families have eaten their seed reserves and have nothing to plant next year. Damana lies south of the 14th parallel that cuts across the Sahel region on the Sahara desert and that, experts say, is often an area affected by food shortages. "That area is always precarious, the zone most at risk," states Seidou Bakari, head of Niger's national food crisis unit. Last year swarms of locusts stripped crops and grazing vegetation across the Sahel as the region suffered its worst invasion of the insect swarms for 15 years. And while adequate rain fell in many parts of the Sahel, rainfall was more patchy and ended prematurely on the northern fringes of the region, which are virtually semi-desert. -

The Devils' Dance

THE DEVILS’ DANCE TRANSLATED BY THE DEVILS’ DANCE HAMID ISMAILOV DONALD RAYFIELD TILTED AXIS PRESS POEMS TRANSLATED BY JOHN FARNDON The Devils’ Dance جينلر بازمي The jinn (often spelled djinn) are demonic creatures (the word means ‘hidden from the senses’), imagined by the Arabs to exist long before the emergence of Islam, as a supernatural pre-human race which still interferes with, and sometimes destroys human lives, although magicians and fortunate adventurers, such as Aladdin, may be able to control them. Together with angels and humans, the jinn are the sapient creatures of the world. The jinn entered Iranian mythology (they may even stem from Old Iranian jaini, wicked female demons, or Aramaic ginaye, who were degraded pagan gods). In any case, the jinn enthralled Uzbek imagination. In the 1930s, Stalin’s secret police, inveigling, torturing and then executing Uzbekistan’s writers and scholars, seemed to their victims to be the latest incarnation of the jinn. The word bazm, however, has different origins: an old Iranian word, found in pre-Islamic Manichaean texts, and even in what little we know of the language of the Parthians, it originally meant ‘a meal’. Then it expanded to ‘festivities’, and now, in Iran, Pakistan and Uzbekistan, it implies a riotous party with food, drink, song, poetry and, above all, dance, as unfettered and enjoyable as Islam permits. I buried inside me the spark of love, Deep in the canyons of my brain. Yet the spark burned fiercely on And inflicted endless pain. When I heard ‘Be happy’ in calls to prayer It struck me as an evil lure. -

Agriculture and the State of Food Insecurity in Western Africa

Agriculture and the State of Food Insecurity in Western Africa Emmanuel Mensah Graduate Research Assistant Department of Agricultural Sciences, West Texas A&M University, WTAMU Box 60998, Canyon, Texas 79016 [email protected] Lal K. Almas Fulbright Scholar and Professor of Agricultural Business and Economics, Department of Agricultural Sciences, West Texas A&M University, WTAMU Box 60998, Canyon, Texas 79016 [email protected] Bridget L. Guerrero Assistant Professor of Agricultural Business and Economics Department of Agricultural Sciences, West Texas A&M University WTAMU Box 60998, Canyon, Texas 79016 [email protected] David G. Lust Associate Professor of Animal Science Department of Agricultural Sciences, West Texas A&M University WTAMU Box 60998, Canyon, Texas 79016 [email protected] Muslum Ibrahimov Visiting Fulbright Scholar at WTAMU Azerbaijan State Economic University, Baku, Azerbaijan [email protected] Selected Paper prepared for presentation at the Southern Agricultural Economics Association 48th Annual Meeting, San Antonio, Texas, February 6-9, 2016 Abstract: The world demand for food is growing rapidly due to population increase. Agriculture is expected to play a leading role of feeding a global population that will number 9.6 billion in 2050, while providing income, employment and environmental services. The study assesses agriculture and the state of food insecurity in Western Africa. In the light of slow progress in food security, it is suggested that investments in the agricultural sector that will increase food availability and strengthen the food production system in West Africa should be given immediate priority especially the innovation of family/smallholder farming. Copyright 2016 by Emmanuel Mensah, Lal Almas, Bridget Guerrero and David Lust. -

Jews: Politics, Race, Nently Because, As Corwin Berman Explains, It Last Month, Was Cancelled Due to Inclement Many Are Trying to Revitalize It

Washtenaw Jewish News Presort Standard In this issue… c/o Jewish Federation of Greater Ann Arbor U.S. Postage PAID 2939 Birch Hollow Drive Ann Arbor, MI Ann Arbor, MI 48108 Permit No. 85 Modern Multi-faith For this year's Day aid for hamentashen, Queen Syrian hold the jam Esthers refugees page 7 page 18 page 28 March 2015 Adar/Nisan 5775 Volume XXXIX: Number 6 FREE “We Refuse to Be Enemies”—motto of Hand in Hand Schools in Israel Edible Landscape program Helena Robinovitz, special to the WJN rescheduled for March 15 he weekend of March 20–22, Lee Gor- cultures. Together the Jewish and Arab pupils study, to play, to live with Palestinian partners.” Carole Caplan, special to the WJN don, co-founder and executive director learn and speak each other’s language, study (Boston Globe, “Refusing to be Enemies in Jeru- The Jewish Alliance for Food, Land and Justice, T of five bilingual and bicultural schools each other’s history and culture, and share in salem,” December 7, 2014.) in partnership with the Ann Arbor Recon- in Israel, will be in Ann Arbor to educate the The structure structionist Congregation and Pardes Hannah, community about this innovative model of of the HIH Schools will present “Ed- education. On Saturday, March 21, 8–10 p.m., provides an oppor- ible Home Land- there will be an interfaith event at St. Clare’s tunity for interac- scapes—From Episcopal/Temple Beth Emeth. The topic will tion that naturally Saving Seeds to be “Building a Shared Society Together: Multi- evolves between stu- Harvesting Your cultural Education and Peacemaking in Israel.” dents and families in Trees” on March On Sunday, March 22, 4–6 p.m., the Jewish Fed- an integrated school 15, from 2–4 eration of Greater Ann Arbor will host Gordon system. -

Roti As Part of Food Exchange List

IOSR Journal of Nursing and Health Science (IOSR-JNHS) e-ISSN: 2320–1959.p- ISSN: 2320–1940 Volume 4, Issue 3 Ver. III (May. - Jun. 2015), PP 87-90 www.iosrjournals.org Estimation of Macronutrient Content of Traditional Pakistani Chapatti/ Roti as Part of Food Exchange List Ms. Mahnaz Nasir Khan1, Dr. Samia Kalsoom2, Dr. Ayyaz Ali Khan3 1(Assistant Professor, Food Science and Human Nutrition, Kinnaird College for Women, Lahore, Pakistan) 2(Professor, Government College of Home Economics, Lahore, Pakistan) 3(Doctor, Federal Postgraduate Medical Institute, Shaikh Zayed Medical Complex, Lahore, Pakistan) Abstract: This is a small base-line study where the researcher has made a unique attempt to disseminate the varying size of chapatti into the exchange list. Chapatti as it is a staple food of Pakistan and was assessed for its size and corresponding weight so that it could be incorporated as part of the carbohydrate exchange list. Though chapatti is served with the main course of every Pakistani cuisine yet its size and weight has not been standardized and difference in size and weight will lead to varying nutrient content and consequently number of exchanges. Chapattis of three different sizes were prepared in the Food Laboratory of Food Science & Human Nutrition Department, Kinnaird College for Women, Lahore. 9 experiments were carried out and three chapattis large, medium and small were prepared using 100grams, 75 grams and 50 grams of dry flour respectively. The results revealed that small chapatti (6inch diameter) contributed 37.5 grams of carbohydrate which in turn were converted to 2.5 carbohydrate exchanges. -

1 Centro Vasco New York

12 THE BASQUES OF NEW YORK: A Cosmopolitan Experience Gloria Totoricagüena With the collaboration of Emilia Sarriugarte Doyaga and Anna M. Renteria Aguirre TOTORICAGÜENA, Gloria The Basques of New York : a cosmopolitan experience / Gloria Totoricagüena ; with the collaboration of Emilia Sarriugarte Doyaga and Anna M. Renteria Aguirre. – 1ª ed. – Vitoria-Gasteiz : Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia = Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco, 2003 p. ; cm. – (Urazandi ; 12) ISBN 84-457-2012-0 1. Vascos-Nueva York. I. Sarriugarte Doyaga, Emilia. II. Renteria Aguirre, Anna M. III. Euskadi. Presidencia. IV. Título. V. Serie 9(1.460.15:747 Nueva York) Edición: 1.a junio 2003 Tirada: 750 ejemplares © Administración de la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco Presidencia del Gobierno Director de la colección: Josu Legarreta Bilbao Internet: www.euskadi.net Edita: Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia - Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco Donostia-San Sebastián, 1 - 01010 Vitoria-Gasteiz Diseño: Canaldirecto Fotocomposición: Elkar, S.COOP. Larrondo Beheko Etorbidea, Edif. 4 – 48180 LOIU (Bizkaia) Impresión: Elkar, S.COOP. ISBN: 84-457-2012-0 84-457-1914-9 D.L.: BI-1626/03 Nota: El Departamento editor de esta publicación no se responsabiliza de las opiniones vertidas a lo largo de las páginas de esta colección Index Aurkezpena / Presentation............................................................................... 10 Hitzaurrea / Preface......................................................................................... -

Three Colomns-ML Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results

Three colomns-ML Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results DBA CUISINE DESCRIPTION DUNKIN Donuts ALL ABOUT INDIAN FOOD Indian CHARLIES SPORTS BAR Bottled Beverages MIMMO Italian SUENOS AMERICANO BAR Spanish RESTAURANT ANN & TONY'S RESTAURANT Italian GREEN BEAN CAFE Coffee/Tea PORTO BELLO PIZZERIA & Pizza RESTAURANT GUESTHOUSE RESTAURANT Eastern European CALEXICO CARNE ASADA Mexican JOHNNY UTAHS American RUMOURS American FORDHAM RESTAURANT American HONG KONG CAFE CHINESE Chinese RESTAURANT ASTORIA SEAFOOD & GRILL Seafood SUP CRAB SEAFOOD RESTAURANT Chinese SWEETCATCH POKE Hawaiian SWEETCATCH POKE Hawaiian Page 1 of 488 09/29/2021 Three colomns-ML Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results INSPECTION DATE 11/18/2019 09/15/2021 11/24/2018 03/12/2020 01/03/2020 02/19/2019 01/16/2020 07/06/2017 04/24/2018 04/19/2018 06/20/2018 12/12/2019 09/10/2019 05/14/2018 08/19/2019 08/27/2019 06/24/2019 06/24/2019 Page 2 of 488 09/29/2021 Three colomns-ML Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results KAHLO Mexican 52ND SUSHI Japanese EL COFRE RESTAURANT Latin American CARVEL Frozen Desserts CHOPSTICKS Chinese CATRIA MODERN ITALIAN Italian CATRIA MODERN ITALIAN Italian TAGLIARE PIZZA DELTA TERMINAL American OVERLOOK American BILLIARD COMPANY American BOCADITO BISTRO Eastern European FINN'S BAGELS Coffee/Tea FINN'S BAGELS Coffee/Tea CHUAN TIAN XIA Chinese LA POSADA MEXICAN FOOD Mexican CHINA STAR QUEENS CHINESE Chinese RESTAURANT AC HOTEL NEW YORK DOWNTOWN American NEWTOWN Middle Eastern NO.1 CALLE 191 PESCADERIA