Biodiversity Blitz Outline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparative Osteology and Evolution of the Lungless Salamanders, Family Plethodontidae David B

COMPARATIVE OSTEOLOGY AND EVOLUTION OF THE LUNGLESS SALAMANDERS, FAMILY PLETHODONTIDAE DAVID B. WAKE1 ABSTRACT: Lungless salamanders of the family Plethodontidae comprise the largest and most diverse group of tailed amphibians. An evolutionary morphological approach has been employed to elucidate evolutionary rela tionships, patterns and trends within the family. Comparative osteology has been emphasized and skeletons of all twenty-three genera and three-fourths of the one hundred eighty-three species have been studied. A detailed osteological analysis includes consideration of the evolution of each element as well as the functional unit of which it is a part. Functional and developmental aspects are stressed. A new classification is suggested, based on osteological and other char acters. The subfamily Desmognathinae includes the genera Desmognathus, Leurognathus, and Phaeognathus. Members of the subfamily Plethodontinae are placed in three tribes. The tribe Hemidactyliini includes the genera Gyri nophilus, Pseudotriton, Stereochilus, Eurycea, Typhlomolge, and Hemidac tylium. The genera Plethodon, Aneides, and Ensatina comprise the tribe Pleth odontini. The highly diversified tribe Bolitoglossini includes three super genera. The supergenera Hydromantes and Batrachoseps include the nominal genera only. The supergenus Bolitoglossa includes Bolitoglossa, Oedipina, Pseudoeurycea, Chiropterotriton, Parvimolge, Lineatriton, and Thorius. Manculus is considered to be congeneric with Eurycea, and Magnadig ita is congeneric with Bolitoglossa. Two species are assigned to Typhlomolge, which is recognized as a genus distinct from Eurycea. No. new information is available concerning Haptoglossa. Recognition of a family Desmognathidae is rejected. All genera are defined and suprageneric groupings are defined and char acterized. Range maps are presented for all genera. Relationships of all genera are discussed. -

Pseudoeurycea Naucampatepetl. the Cofre De Perote Salamander Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico. This

Pseudoeurycea naucampatepetl. The Cofre de Perote salamander is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This relatively large salamander (reported to attain a total length of 150 mm) is recorded only from, “a narrow ridge extending east from Cofre de Perote and terminating [on] a small peak (Cerro Volcancillo) at the type locality,” in central Veracruz, at elevations from 2,500 to 3,000 m (Amphibian Species of the World website). Pseudoeurycea naucampatepetl has been assigned to the P. bellii complex of the P. bellii group (Raffaëlli 2007) and is considered most closely related to P. gigantea, a species endemic to the La specimens and has not been seen for 20 years, despite thorough surveys in 2003 and 2004 (EDGE; www.edgeofexistence.org), and thus it might be extinct. The habitat at the type locality (pine-oak forest with abundant bunch grass) lies within Lower Montane Wet Forest (Wilson and Johnson 2010; IUCN Red List website [accessed 21 April 2013]). The known specimens were “found beneath the surface of roadside banks” (www.edgeofexistence.org) along the road to Las Lajas Microwave Station, 15 kilometers (by road) south of Highway 140 from Las Vigas, Veracruz (Amphibian Species of the World website). This species is terrestrial and presumed to reproduce by direct development. Pseudoeurycea naucampatepetl is placed as number 89 in the top 100 Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered amphib- ians (EDGE; www.edgeofexistence.org). We calculated this animal’s EVS as 17, which is in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its IUCN status has been assessed as Critically Endangered. -

1 Southeastern Us Coastal Plain

1 In Press: 2000. Chapter XX. Pages __-__ in Richard C. Bruce, Robert J. Jaeger, and Lynn D. Houck, editors. The Biology of the Plethodontidae. Plenum Publishing Corp., New York, N. Y. SOUTHEASTERN U. S. COASTAL PLAIN HABITATS OF THE PLETHODONTIDAE: THE IMPORTANCE OF RELIEF, RAVINES, AND SEEPAGE D. BRUCE MEANS Coastal Plains Institute and Land Conservancy, 1313 N. Duval Street, Tallahassee, FL 32303, USA 1. INTRODUCTION Because the Coastal Plain is geologically and biologically a very distinct region of the southeastern United States -- the southern portion having a nearly subtropical climate -- the life cycles, ecology, and evolutionary relationships of its plethodontid salamanders may be significantly different from plethodontids in the Appalachians and Piedmont. Little attention has been paid, however, to Coastal Plain plethodontids. For instance, of the 133 scientific papers and posters presented at the four plethodontid salamander conferences held in Highlands, North Carolina, since 1972, only three (2%) dealt with Coastal Plain plethodontids. And yet, while it possesses fewer total species than the Appalachians and Piedmont, the Coastal Plain boasts of slightly more plethodontid diversity at the generic level. The genera Phaeognathus, Haideotriton, and Stereochilus are Coastal Plain endemics, whereas in the Appalachians and Piedmont Gyrinophilus is the only endemic genus unless one accepts Leurognathus apart from Desmognathus. In addition, Aneides is found in the Appalachians and not the Coastal Plain, but the genus also occurs in the western U. S. All the rest of the plethodontid genera east of the Mississippi River are shared by the Coastal Plain with the Appalachians and Piedmont. Geographically, the Coastal Plain includes Long Island in New York, and stretches south from the New Jersey Pine Barrens to include all of Florida, then west to Texas (Fig. -

50 CFR Ch. I (10–1–20 Edition) § 16.14

§ 15.41 50 CFR Ch. I (10–1–20 Edition) Species Common name Serinus canaria ............................................................. Common Canary. 1 Note: Permits are still required for this species under part 17 of this chapter. (b) Non-captive-bred species. The list 16.14 Importation of live or dead amphib- in this paragraph includes species of ians or their eggs. non-captive-bred exotic birds and coun- 16.15 Importation of live reptiles or their tries for which importation into the eggs. United States is not prohibited by sec- Subpart C—Permits tion 15.11. The species are grouped tax- onomically by order, and may only be 16.22 Injurious wildlife permits. imported from the approved country, except as provided under a permit Subpart D—Additional Exemptions issued pursuant to subpart C of this 16.32 Importation by Federal agencies. part. 16.33 Importation of natural-history speci- [59 FR 62262, Dec. 2, 1994, as amended at 61 mens. FR 2093, Jan. 24, 1996; 82 FR 16540, Apr. 5, AUTHORITY: 18 U.S.C. 42. 2017] SOURCE: 39 FR 1169, Jan. 4, 1974, unless oth- erwise noted. Subpart E—Qualifying Facilities Breeding Exotic Birds in Captivity Subpart A—Introduction § 15.41 Criteria for including facilities as qualifying for imports. [Re- § 16.1 Purpose of regulations. served] The regulations contained in this part implement the Lacey Act (18 § 15.42 List of foreign qualifying breed- U.S.C. 42). ing facilities. [Reserved] § 16.2 Scope of regulations. Subpart F—List of Prohibited Spe- The provisions of this part are in ad- cies Not Listed in the Appen- dition to, and are not in lieu of, other dices to the Convention regulations of this subchapter B which may require a permit or prescribe addi- § 15.51 Criteria for including species tional restrictions or conditions for the and countries in the prohibited list. -

Minelli-Et-Al(Eds)

ZOOTAXA 1950 Updating the Linnaean Heritage: Names as Tools for Thinking about Animals and Plants ALESSANDRO MINELLI, LUCIO BONATO & GIUSEPPE FUSCO (EDS) Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand ALESSANDRO MINELLI, LUCIO BONATO & GIUSEPPE FUSCO (EDS) Updating the Linnaean Heritage: Names as Tools for Thinking about Animals and Plants (Zootaxa 1950) 163 pp.; 30 cm. 5 Dec. 2008 ISBN 978-1-86977-297-0 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-86977-298-7 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2008 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2008 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) Zootaxa 1950: 3–4 (2008) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2008 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Updating the Linnaean Heritage: Names as Tools for Thinking about Animals and Plants ALESSANDRO MINELLI FLS, LUCIO BONATO & GIUSEPPE FUSCO (EDS) Department of Biology, University of Padova, Via Ugo Bassi 58B, I 35131 Padova, Italy Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Table of contents 4 Preface ALESSANDRO MINELLI FLS, LUCIO BONATO, GIUSEPPE FUSCO (ITALY) 5 Actual usage of biological nomenclature and its implications for data integrators; a national, regional and global perspective CHARLES HUSSEY (UK), YDE DE JONG (THE NETHERLANDS), DAVID REMSEN (DENMARK) 9 The Linnean foundations of zoological and botanical nomenclature OTTO KRAUS (GERMANY) 21 Zoological vs. -

The Salamanders of Tennessee

Salamanders of Tennessee: modified from Lisa Powers tnwildlife.org Follow links to Nongame The Salamanders of Tennessee Photo by John White Salamanders are the group of tailed, vertebrate animals that along with frogs and caecilians make up the class Amphibia. Salamanders are ectothermic (cold-blooded), have smooth glandular skin, lack claws and must have a moist environment in which to live. 1 Amphibian Declines Worldwide, over 200 amphibian species have experienced recent population declines. Scientists have reports of 32 species First discovered in 1967, the golden extinctions, toad, Bufo periglenes, was last seen mainly species of in 1987. frogs. Much attention has been given to the Anurans (frogs) in recent years, however salamander populations have been poorly monitored. Photo by Henk Wallays Fire Salamander - Salamandra salamandra terrestris 2 Why The Concern For Salamanders in Tennessee? Their key role and high densities in many forests The stability in their counts and populations Their vulnerability to air and water pollution Their sensitivity as a measure of change The threatened and endangered status of several species Their inherent beauty and appeal as a creature to study and conserve. *Possible Factors Influencing Declines Around the World Climate Change Habitat Modification Habitat Fragmentation Introduced Species UV-B Radiation Chemical Contaminants Disease Trade in Amphibians as Pets *Often declines are caused by a combination of factors and do not have a single cause. Major Causes for Declines in Tennessee Habitat Modification -The destruction of natural habitats is undoubtedly the biggest threat facing amphibians in Tennessee. Housing, shopping center, industrial and highway construction are all increasing throughout the state and consequently decreasing the amount of available habitat for amphibians. -

Amphibian and Reptile Checklist

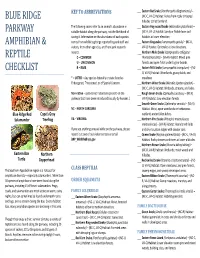

KEY TO ABBREVIATIONS ___ Eastern Rat Snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) – BLUE RIDGE (NC‐C, VA‐C) Habitat: Varies from rocky timbered hillsides to flat farmland. The following codes refer to an animal’s abundance in ___ Eastern Hog‐nosed Snake (Heterodon platirhinos) – PARKWAY suitable habitat along the parkway, not the likelihood of (NC‐R, VA‐U) Habitat: Sandy or friable loam soil seeing it. Information on the abundance of each species habitats at lower elevation. AMPHIBIAN & comes from wildlife sightings reported by park staff and ___ Eastern Kingsnake (Lampropeltis getula) – (NC‐U, visitors, from other agencies, and from park research VA‐U) Habitat: Generalist at low elevations. reports. ___ Northern Mole Snake (Lampropeltis calligaster REPTILE C – COMMON rhombomaculata) – (VA‐R) Habitat: Mixed pine U – UNCOMMON forests and open fields under logs or boards. CHECKLIST R – RARE ___ Eastern Milk Snake (Lampropeltis triangulum) – (NC‐ U, VA‐U) Habitat: Woodlands, grassy balds, and * – LISTED – Any species federally or state listed as meadows. Endangered, Threatened, or of Special Concern. ___ Northern Water Snake (Nerodia sipedon sipedon) – (NC‐C, VA‐C) Habitat: Wetlands, streams, and lakes. Non‐native – species not historically present on the ___ Rough Green Snake (Opheodrys aestivus) – (NC‐R, parkway that have been introduced (usually by humans.) VA‐R) Habitat: Low elevation forests. ___ Smooth Green Snake (Opheodrys vernalis) – (VA‐R) NC – NORTH CAROLINA Habitat: Moist, open woodlands or herbaceous Blue Ridge Red Cope's Gray wetlands under fallen debris. Salamander Treefrog VA – VIRGINIA ___ Northern Pine Snake (Pituophis melanoleucus melanoleucus) – (VA‐R) Habitat: Abandoned fields If you see anything unusual while on the parkway, please and dry mountain ridges with sandier soils. -

THE CONTRIBUTION of HEADWATER STREAMS to BIODIVERSITY in RIVER Networksl

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN WATER RESOURCES ASSOCIATION Vol. 43, No.1 AMERICAN WATER RESOURCES ASSOCIATION February 2007 THE CONTRIBUTION OF HEADWATER STREAMS TO BIODIVERSITY IN RIVER NETWORKSl Judy L. Meyer, David L. Strayer, J. Bruce Wallace, Sue L. Eggert, Gene S. Helfman, and Norman E. Leonard2 ABSTRACT: The diversity of life in headwater streams (intermittent, first and second order) contributes to the biodiversity of a river system and its riparian network. Small streams differ widely in physical, chemical, and biotic attributes, thus providing habitats for a range of unique species. Headwater species include permanent residents as well as migrants that travel to headwaters at particular seasons or life stages. Movement by migrants links headwaters with downstream and terrestrial ecosystems, as do exports such as emerging and drifting insects. We review the diversity of taxa dependent on headwaters. Exemplifying this diversity are three unmapped headwaters that support over 290 taxa. Even intermittent streams may support rich and distinctive biological communities, in part because of the predictability of dry periods. The influence of headwaters on downstream systems emerges from their attributes that meet unique habitat requirements of residents and migrants by: offering a refuge from temperature and flow extremes, competitors, predators, and introduced spe cies; serving as a source of colonists; providing spawning sites and rearing areas; being a rich source of food; and creating migration corridors throughout the landscape. Degradation and loss of headwaters and their con nectivity to ecosystems downstream threaten the biological integrity of entire river networks. (KEY TERMS: biotic integrity; intermittent; first-order streams; small streams; invertebrates; fish.) Meyer, Judy L., David L. -

3Systematics and Diversity of Extant Amphibians

Systematics and Diversity of 3 Extant Amphibians he three extant lissamphibian lineages (hereafter amples of classic systematics papers. We present widely referred to by the more common term amphibians) used common names of groups in addition to scientifi c Tare descendants of a common ancestor that lived names, noting also that herpetologists colloquially refer during (or soon after) the Late Carboniferous. Since the to most clades by their scientifi c name (e.g., ranids, am- three lineages diverged, each has evolved unique fea- bystomatids, typhlonectids). tures that defi ne the group; however, salamanders, frogs, A total of 7,303 species of amphibians are recognized and caecelians also share many traits that are evidence and new species—primarily tropical frogs and salaman- of their common ancestry. Two of the most defi nitive of ders—continue to be described. Frogs are far more di- these traits are: verse than salamanders and caecelians combined; more than 6,400 (~88%) of extant amphibian species are frogs, 1. Nearly all amphibians have complex life histories. almost 25% of which have been described in the past Most species undergo metamorphosis from an 15 years. Salamanders comprise more than 660 species, aquatic larva to a terrestrial adult, and even spe- and there are 200 species of caecilians. Amphibian diver- cies that lay terrestrial eggs require moist nest sity is not evenly distributed within families. For example, sites to prevent desiccation. Thus, regardless of more than 65% of extant salamanders are in the family the habitat of the adult, all species of amphibians Plethodontidae, and more than 50% of all frogs are in just are fundamentally tied to water. -

Key to the Identification of Streamside Salamanders

Key to the Identification of Streamside Salamanders Ambystoma spp., mole salamanders (Family Ambystomatidae) Appearance : Medium to large stocky salamanders. Large round heads with bulging eyes . Larvae are also stocky and have elaborate gills. Size: 3-8” (Total length). Spotted salamander, Ambystoma maculatum Habitat: Burrowers that spend much of their life below ground in terrestrial habitats. Some species, (e.g. marbled salamander) may be found under logs or other debris in riparian areas. All species breed in fishless isolated ponds or wetlands. Range: Statewide. Other: Five species in Georgia. This group includes some of the largest and most dramatically patterned terrestrial species. Marbled salamander, Ambystoma opacum Amphiuma spp., amphiuma (Family Amphiumidae) Appearance: Gray to black, eel-like bodies with four greatly reduced, non-functional legs (A). Size: up to 46” (Total length) Habitat: Lakes, ponds, ditches and canals, one species is found in deep pockets of mud along the Apalachicola River floodplains. A Range: Southern half of the state. Other: One species, the two-toed amphiuma ( A. means ), shown on the right, is known to occur in A. pholeter southern Georgia; a second species, ,Two-toed amphiuma, Amphiuma means may occur in extreme southwest Georgia, but has yet to be confirmed. The two-toed amphiuma (shown in photo) has two diminutive toes on each of the front limbs. Cryptobranchus alleganiensis , hellbender (Family Cryptobranchidae) Appearance: Very large, wrinkled salamander with eyes positioned laterally (A). Brown-gray in color with darker splotches Size: 12-29” (Total length) A Habitat: Large, rocky, fast-flowing streams. Often found beneath large rocks in shallow rapids. Range: Extreme northern Georgia only. -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L. -

Terrestrial Ecosystems 3 Chapter 1

TERRESTRIAL Chapter 1: Terrestrial Ecosystems 3 Chapter 1: What are the history, Terrestrial status, and projected future of terrestrial wildlife habitat types and Ecosystems species in the South? Margaret Katherine Trani (Griep) Southern Region, USDA Forest Service ■ Since presettlement, there have insect infestation, advanced age, Key Findings been significant losses of community climatic processes, and distur- biodiversity in the South (Noss and bance influence mast yields. ■ There are 132 terrestrial vertebrate others 1995). Fourteen communities ■ The ranges of many species species that are considered to be are critically endangered (greater cross both public and private of conservation concern in the South than 98-percent decline), 25 are land ownerships. The numbers of by State Natural Heritage agencies. endangered (85- to 98-percent imperiled and endangered species Of the species that warrant conser- decline), and 11 are threatened inhabiting private land indicate its vation focus, 3 percent are classed (70- to 84-percent decline). Common critical importance for conservation. factors contributing to the loss of as critically imperiled, 3 percent ■ The significance of land owner- as imperiled, and 6 percent as these communities include urban development, fire suppression, ship in the South for the provision vulnerable. Eighty-six percent of species habitat cannot be of terrestrial vertebrate species exotic species invasion, and recreational activity. overstated. Each major landowner are designated as relatively secure. has an important role to play in ■ The remaining 2 percent are either The term “fragmentation” the conservation of species and known or presumed to be extinct, references the insularization of their habitats. or have questionable status. habitat on a landscape.