The Journal of Studies in Language, Culture and Society (JSLCS)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Is Language Typology Possible?

Why is language typology possible? Martin Haspelmath 1 Languages are incomparable Each language has its own system. Each language has its own categories. Each language is a world of its own. 2 Or are all languages like Latin? nominative the book genitive of the book dative to the book accusative the book ablative from the book 3 Or are all languages like English? 4 How could languages be compared? If languages are so different: What could be possible tertia comparationis (= entities that are identical across comparanda and thus permit comparison)? 5 Three approaches • Indeed, language typology is impossible (non- aprioristic structuralism) • Typology is possible based on cross-linguistic categories (aprioristic generativism) • Typology is possible without cross-linguistic categories (non-aprioristic typology) 6 Non-aprioristic structuralism: Franz Boas (1858-1942) The categories chosen for description in the Handbook “depend entirely on the inner form of each language...” Boas, Franz. 1911. Introduction to The Handbook of American Indian Languages. 7 Non-aprioristic structuralism: Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) “dans la langue il n’y a que des différences...” (In a language there are only differences) i.e. all categories are determined by the ways in which they differ from other categories, and each language has different ways of cutting up the sound space and the meaning space de Saussure, Ferdinand. 1915. Cours de linguistique générale. 8 Example: Datives across languages cf. Haspelmath, Martin. 2003. The geometry of grammatical meaning: semantic maps and cross-linguistic comparison 9 Example: Datives across languages 10 Example: Datives across languages 11 Non-aprioristic structuralism: Peter H. Matthews (University of Cambridge) Matthews 1997:199: "To ask whether a language 'has' some category is...to ask a fairly sophisticated question.. -

Isydma'5 Virtual Edition

ISyDMA’5 Virtual Edition ISyDMA’5 Virtual Edition 15-17 April 2020 Page 1 The Fifth International Symposium on Dielectric Materials and Applications Faculty of Science Semlalia Cadi Ayyad University, Morocco, 15-17 April 2020 Fifth edition of International Symposium on Dielectric Materials and Applications ISyDMA’5 Virtual Edition April 15-17, 2020 Organized by Cadi Ayyad University, Marrakech Faculty of Sciences Semlalia, Marrakech Moroccan Society of Applied Physics Moroccan Association of Advanced Materials (A2MA). In cooperation with: Ibn Tofail University, Kenitra, Morocco Soltan Moulay Sliman University, Beni Mellal, Morocco University of Miami, Florida, USA Ibn Zohr University, Agadir, Morocco ISyDMA’5 Virtual Edition 15-17 April 2020 Page 2 The Fifth International Symposium on Dielectric Materials and Applications Faculty of Science Semlalia Cadi Ayyad University, Morocco, 15-17 April 2020 M O R O C C A N A SSOCIATION OF Organizers & Partners A D V A N C E D M ATERIALS M O R O C C A N A SSOCIATION O F A D V A N C E D M ATERIALSX ISyDMA’5 Virtual Edition 15-17 April 2020 Page 3 The Fifth International Symposium on Dielectric Materials and Applications Faculty of Science Semlalia Cadi Ayyad University, Morocco, 15-17 April 2020 Contacts Prof. ACHOUR Mohammed Essaid Conference Chairman Faculty of Sciences, Ibn Tofail University, Kenitra, Morocco email: [email protected] Phone: +212 766207680 Prof. AIT ALI Mustapha Conference Chairman Faculty of Sciences Semlalia, Cadi Ayyad Univeristy, Marrakech, Morocco email: [email protected] Phone: +212 666935170 Prof. OUERIAGLI Amane Conference Chairman Faculty of Sciences Semlalia, Cadi Ayyad Univeristy, Marrakech, Morocco email: [email protected] ISyDMA’5 Virtual Edition 15-17 April 2020 Page 4 The Fifth International Symposium on Dielectric Materials and Applications Faculty of Science Semlalia Cadi Ayyad University, Morocco, 15-17 April 2020 Welcome message Greetings from the ISyDMA’5 organizers. -

Policy Studies in Language and Cross-Cultural Education in the College of Education

Policy Studies in Language and Cross-Cultural Education In the College of Education OFFICE: Education and Business Administration 248 PLC 553. Language Assessment and Evaluation in Multicultural TELEPHONE: 619-594-5155 / FAX: 619-594-1183 Settings (3) Theories and methods of assessment and evaluation of diverse http://edweb.sdsu.edu/PLC/ student populations including authentic and traditional models. Procedures for identification, placement, and monitoring of linguisti- Faculty cally diverse students. Theories, models, and methods for program evaluation, achievement, and decision making. Alberto J. Rodriguez, Ph.D., Professor of Policy Studies in Language and Cross-Cultural Education, Interim Chair of Department PLC 596. Special Topics in Bilingual and Multicultural Karen Cadiero-Kaplan, Ph.D., Professor of Policy Studies in Language Education (1-3) and Cross-Cultural Education (Graduate Adviser) Prerequisite: Consent of instructor. Alberto M. Ochoa, Ph.D., Professor of Policy Studies in Language and Selected topics in bilingual, cross-cultural education and policy Cross-Cultural Education, Emeritus studies. May be repeated with new content. See Class Schedule for Cristina Alfaro, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Policy Studies in specific content. Credit for 596 and 696 applicable to a master's Language and Cross-Cultural Education degree with approval of the graduate adviser. Cristian Aquino-Sterling, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Policy Studies in GRADUATE COURSES Language and Cross-Cultural Education Elsa S. Billings, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Policy Studies in PLC 600A. Foundations of Democratic Schooling (3) Language and Cross-Cultural Education Prerequisite: Consent of instructor. Analysis of relationships among ideology, culture, and power in educational context; key concepts in critical pedagogy applied to Courses Acceptable on Master’s Degree programs, curricula, and school restructuring. -

Mecca of Revolution Oxford Studies in International History

Mecca of Revolution Oxford Studies in International History James J. Sheehan, series advisor The Wilsonian Moment Self- Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism Erez Manela In War’s Wake Europe’s Displaced Persons in the Postwar Order Gerard Daniel Cohen Grounds of Judgment Extraterritoriality and Imperial Power in Nineteenth- Century China and Japan Pär Kristoffer Cassel The Acadian Diaspora An Eighteenth- Century History Christopher Hodson Gordian Knot Apartheid and the Unmaking of the Liberal World Order Ryan Irwin The Global Offensive The United States, the Palestine Liberation Organization, and the Making of the Post– Cold War Order Paul Thomas Chamberlin Mecca of Revolution Algeria, Decolonization, and the Third World Order Jeffrey James Byrne Mecca of Revolution Algeria, Decolonization, and the Third World Order JEFFREY JAMES BYRNE 1 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America. © Oxford University Press 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. -

Modeling Language Variation and Universals: a Survey on Typological Linguistics for Natural Language Processing

Modeling Language Variation and Universals: A Survey on Typological Linguistics for Natural Language Processing Edoardo Ponti, Helen O ’Horan, Yevgeni Berzak, Ivan Vulic, Roi Reichart, Thierry Poibeau, Ekaterina Shutova, Anna Korhonen To cite this version: Edoardo Ponti, Helen O ’Horan, Yevgeni Berzak, Ivan Vulic, Roi Reichart, et al.. Modeling Language Variation and Universals: A Survey on Typological Linguistics for Natural Language Processing. 2018. hal-01856176 HAL Id: hal-01856176 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01856176 Preprint submitted on 9 Aug 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Modeling Language Variation and Universals: A Survey on Typological Linguistics for Natural Language Processing Edoardo Maria Ponti∗ Helen O’Horan∗∗ LTL, University of Cambridge LTL, University of Cambridge Yevgeni Berzaky Ivan Vuli´cz Department of Brain and Cognitive LTL, University of Cambridge Sciences, MIT Roi Reichart§ Thierry Poibeau# Faculty of Industrial Engineering and LATTICE Lab, CNRS and ENS/PSL and Management, Technion - IIT Univ. Sorbonne nouvelle/USPC Ekaterina Shutova** Anna Korhonenyy ILLC, University of Amsterdam LTL, University of Cambridge Understanding cross-lingual variation is essential for the development of effective multilingual natural language processing (NLP) applications. -

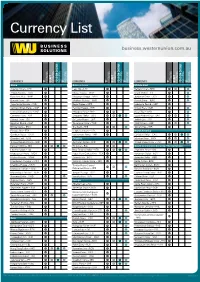

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

CEMA Regular Lecture Series, 2011-2012

Volume 2 November 2012 CEMA Centre d’Études Maghrébines en Algérie Newsletter Letter from the Director, Dr. CEMA Special Lecture Series: CEMA Activities at a Glance Robert P. Parks, and Letter The Saharan Lectures & The Pages 5-9 from Associate Director, Dr. CEMA Public Health Lecture Karim Ouaras Series Outreach, AIMS 2013 CFP, Page 2-3 Page 4 Scholars, Recent Publications Pages 10-14 ; Volume Volume 22 2 NovemberNovember 20122012 Letter from CEMA Director, Dr. Robert P. Parks 2011-2012 has been an exciting year at CEMA. Between November 2011 and October 2012, more than 90 researchers spoke at CEMA activities – at fifteen lectures, two thematic round-table activities, two symposia, one six-week fellowship, and one three-day conference. CEMA assisted the research of 47 American and international scholars. And we received nearly 6,500 walk-in visits to the center. Activity is booming and as CEMA grows, so does its audience. We hope to be able to expand our activities to Algiers and the universities and research institutes of the Center of the country this year. Programmatically, we have been active. This year CEMA organized twelve lectures as part of its regular lecture series, which primarily highlights new or on-going research in history, politics, and sociology. CEMA also organizes three special lecture series: ‘the Oran Lecture,’ ‘the Saharan Lectures,’ and a new series on Public Health. ‘The Oran Lecture,’ which we hope to recommence this year, highlights the research of non-Orani Maghrebi scholars in the social sciences and the humanities. Co- organized with the National Research Center for Social and Cultural Anthropology (CRASC), ‘The Saharan Lectures’ builds from the AIMS-West African Research Association (WARA) Saharan Crossroads Initiative, which seeks to underscore the cultural, economic, and social links between the Maghreb and Sahel region. -

An Empirical Test of Purchasing Power Parity of the Algerian Exchange Rate: Evidence from Panel Dynamic

Munich Personal RePEc Archive An Empirical Test of Purchasing Power Parity of the Algerian Exchange Rate: Evidence from Panel Dynamic Si Mohammed, Kamel and Chérif touil, Noreddine and Maliki, Samir University of Ain Temouchent, University of Mostaganem, University of Tlemcen November 2015 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/75285/ MPRA Paper No. 75285, posted 28 Nov 2016 10:24 UTC An Empirical Test of Purchasing Power Parity of the Algerian Exchange Rate: Evidence from Panel Dynamic Kamel Si Mohammed, (PhD economics) Assistant Professor, Ain Temouchent University, Algeria Noreddine Chérif Touil PhD in economy, Associate Professor, Mostaganem University, Algeria Samir MALIKI PhD , Full Professor, Tlemcen University, Algeria [email protected] Abstract: The goal of this study is to examine the validity of the long-run purchasing power parity (PPP) for a sample of nine principle trade partners of Algeria namely Canada, China, Japan, Switzerland, Sweden, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States and the euro zone countries. Using panel error correction model (PECM) upon monthly data for the period 2003 M1 – 2015M5, results suggested that the bilateral exchange rate movements is a suitable to support the purchasing power parity (PPP) hypothesis. However, suggesting that there is long run relationship between exchange rates and relative prices in foreign courtiers by using panel cointegraion of Pedroni (1999, 2004), that can be interpreted by the validity of purchasing power parity for nine principle trade partners of Algeria. Key Words: (Algeria, panel cointegration, Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), panel error correction model (PECM) 1 I. Introduction: Since 1996, the Bank of Algeria (Central Bank) adopted the floating exchange rate regime after a long period from 1997 to 1996 characterized by a strong dominance of the reference to US dollars due to the particularity of Algerian economy, an economy based on exports of oil - 98percent of export revenues paid in US dollars and imports, rising continuously, paid in euro ((Kamel et al, 2014). -

ANZAMEMS 2017 Abstracts

ANZAMEMS 2017 abstracts Catherine Abou-Nemeh Victoria University of Wellington “Opening the King’s Body: Autopsy and Anatomy in Early Modern Paris” On 1 September 1715, King Louis XIV of France died in his bed in Versailles. The next day several physicians, anatomists, and attendees assembled in the palace to carry out a post-mortem examination of the deceased monarch. In addition to the Dean of the Paris Faculty of Medicine Jean- Baptiste Doye, Guy Fagon (the king’s head physician) and Georges Mareschal (the king’s first- surgeon) led the dissection. This paper situates Louis’ autopsy in the context of late seventeenth and early eighteenth century anatomical practices in Paris. In so doing, I will assess the meaning and status of autopsy, and discuss its relation to royal power and anatomical knowledge. Anya Adair Yale University “The Post-Mortem Mobility of Dead Text: Mouvance and the Early English Legal Preface.” The introduction to a medieval law code does important rhetorical work: among other things, it must convince its audience of the justice of the laws that follow. For authority on this matter, the legal preface (like so many literary texts) often relies on the invocation of an imagined past, founding its claim on past codes, past kings, and a shared sense of stable legal history. Yet the law code itself moves through time in a very different way: in strictly legal terms, the most recent code must take precedence, overriding and erasing past laws. Laws look forward, not back. This paper explores some of the consequences of the temporal tension between prologue and laws, and traces its effects into the ways that early medieval law codes were disseminated and preserved in the manuscript record. -

People's Democratic Republic of Algeria

People's Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Mentouri University Constantine Faculty of Letters and Foreign Languages Department of English Code- Switching in the Conversation of Salespersons and Customers in Ain Smara Market (Clothes Section) Thesis submitted to the department of English in partial fulfillement of the requirements of the Master Degree in Applied language Studies Candidate: Supervisor: Zerroug Nassima Dr. Lakehal Ayat Karima 2009 – 2010 Dedications In the name of God, most merciful, most compassionate. This work is dedicated to: My dear mother who has supported me a lot in my life. My father without whom I would not be who I am. All my family, particularly my sister Amel who shared the hard moment with me and encouraged me to go further. My sister Djalila and all my all brothers: Moncef, Skander, Faouzi, Mohsen and Chemseddine. - i - Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere thanks to my supervisor Dr Lakehal Ayat who guided this research and who has generously given her time and expertise to better my work. I am very grateful for her invaluable observations, for her precious advice that she has given me, for her encouragement, support and especially tenderness because she has really treated I like her daughter. A special thank to Dr Ahmed Sid and Dr Athamna for helping me with sources. I would also to express my thanks to all my friends: Nassima, Nedjoua, Zahoua, Ibtissem, Meriem, Nora, Sara, Zineb, Hanane, Souhila and especially to Nouri Nassira for her friendship, knowledge and support to overcome all the obstacles that I faced in this dissertation. -

A Qualitative Analysis of Superstitious Behavior and Performance: How It Starts, Why It Works, and How It Works

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2015 A Qualitative Analysis of Superstitious Behavior and Performance: How it Starts, Why it Works, and How it Works Alexandra A. Farley Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Health and Physical Education Commons Recommended Citation Farley, Alexandra A., "A Qualitative Analysis of Superstitious Behavior and Performance: How it Starts, Why it Works, and How it Works" (2015). WWU Graduate School Collection. 408. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/408 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Qualitative Analysis of Superstitious Behavior and Performance: How it starts, why it works, and how it works By Alexandra Farley Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Masters of Science Kathleen L. Kitto, Dean of Graduate School Advisor Committee ___________________________ Chair, Dr. Linda Keeler ___________________________ Dr. Michelle Mielke ___________________________ Dr. Keith Russell Master’s Thesis In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non-exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. -

Interpreting Zheng Chenggong: the Politics of Dramatizing

, - 'I ., . UN1VERSIlY OF HAWAII UBRARY 3~31 INTERPRETING ZHENG CHENGGONG: THE POLITICS OF DRAMATIZING A HISTORICAL FIGURE IN JAPAN, CHINA, AND TAIWAN (1700-1963) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAW AI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THEATRE AUGUST 2007 By Chong Wang Thesis Committee: Julie A. Iezzi, Chairperson Lurana D. O'Malley Elizabeth Wichmann-Walczak · - ii .' --, L-' ~ J HAWN CB5 \ .H3 \ no. YI,\ © Copyright 2007 By Chong Wang We certity that we have read this thesis and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in Theatre. TIIESIS COMMITTEE Chairperson iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to give my wannest thanks to my family for their strong support. I also want to give my since're thanks to Dr. Julie Iezzi for her careful guidance and tremendous patience during each stage of the writing process. Finally, I want to thank my proofreaders, Takenouchi Kaori and Vance McCoy, without whom this thesis could not have been completed. - . iv ABSTRACT Zheng Chenggong (1624 - 1662) was sired by Chinese merchant-pirate in Hirado, Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan. A general at the end of the Chinese Ming Dynasty, he was a prominent leader of the movement opposing the Manchu Qing Dynasty, and in recovering Taiwan from Dutch colonial occupation in 1661. Honored as a hero in Japan, China, and Taiwan, he has been dramatized in many plays in various theatre forms in Japan (since about 1700), China (since 1906), and Taiwan (since the 1920s).