The Utopian Function of Art and Literature Were in Part an Endeavor to Resolve Them

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Texts and Contributions to a Critical Theory of Society

1 Introduction: Key Texts and Contributions to a Critical Theory of Society Beverley Best, Werner Bonefeld and Chris O’Kane The designation of the Frankfurt School as a known by sympathisers as ‘Café Marx’. It ‘critical theory’ originated in the United was the first Marxist research institute States. It goes back to two articles, one writ- attached to a German University. ten by Max Horkheimer and the other by Since the 1950s, ‘Frankfurt School’ criti- Herbert Marcuse, that were both published in cal theory has become an established, inter- Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung (later Studies nationally recognised ‘brand name’ in the in Philosophy and Social Science) in 1937.1 social and human sciences, which derives The Zeitschrift, published from 1932 to from its institutional association in the 1920s 1941, was the publishing organ of the and again since 1951 with the Institute Institute for Social Research. It gave coher- for Social Research in Frankfurt, (West) ence to what in fact was an internally diverse Germany. From this institutional perspec- and often disagreeing group of heterodox tive, it is the association with the Institute Marxists that hailed from a wide disciplinary that provides the basis for what is considered spectrum, including social psychology critical theory and who is considered to be a (Fromm, Marcuse, Horkheimer), political critical theorist. This Handbook works with economy and state formation (Pollock and and against its branded identification, concre- Neumann), law and constitutional theory tising as well as refuting it. (Kirchheimer, Neumann), political science We retain the moniker ‘Frankfurt School’ (Gurland, Neumann), philosophy and sociol- in the title to distinguish the character of its ogy (Adorno, Horkheimer, Marcuse), culture critical theory from other seemingly non- (Löwenthal, Adorno), musicology (Adorno), traditional approaches to society, including aesthetics (Adorno, Löwenthal, Marcuse) the positivist traditions of Marxist thought, and social technology (Gurland, Marcuse). -

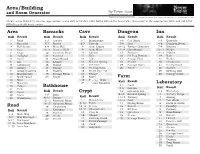

Area-Building and Room Generator

Area/Building By Trevor Scott and Room Generator neverengine.wordpress.com This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Create areas fileld with various, appropriate rooms with a few dice rolls! Roll a d20 on the Area table, then move to the appropriate table and roll a few d20s to generate some rooms. Area Barracks Cave Dungeon Inn Roll Result Roll Result Roll Result Roll Result Roll Result 1 Road 1-3 Armory 1-5 Mushrooms 1-6 Cell Block 1-3 Quarters 2 Barracks 5-7 Bunks 6-7 Cave-In 7-9 Hole 4-6 Common Room 3 Bathhouse 8-9 Mess Hall 8 Area: Crypts 10-12 Torture Chamber 7-9 Kitchen 4 Cave 10-11 Practice Hall 9 Area: Mine 13-14 Guardhouse 10-11 Shrine 5 Crypt 12 Common Room 10 Garden 15 Furnace 12-13 Stables 6 Dungeon 13 Furnace 11 Hole 16 Pit Trap Bottom 14 Bath 7 Farm 14 Guardhouse 12 Lake 17 Sewage Flow 15 Bunks 8 Inn 15 Kennel 13 Natural Spring 18 Shrine 16 Cloakroom 9 Laboratory 16 Shrine 14 Ore Vein 19 Storage Room 17 Dining Room 10 Library 17 Smithy 15 Pit Trap Bottom 20 Tomb 18 Garden 11 Living Quarters 18 Stables 16 Secret Passage 19 Meeting Hall 12 Manufactory 19 Storage Room 17 Sewage Flow 20 Storage Room 13 Marketplace 20 Study 18 Shrine Farm 14 Mine 19 Storage Room Roll Result 15 Museum 20 Torture Chamber Laboratory Palace 1-4 Field 16 Bathhouse Roll Result 17 Park Sample file 5-6 Garden 18 Sewer Roll Result Crypt 7-8 Livestock Pen 1-2 Workshop 1-8 Bath 9-10 Natural Spring 3 Archery Range 19 Slum Roll Result 20 Warehouse 9-11 Sauna 11-12 Tannery 4 Armory 12-13 -

Loneliness of Human in the Philosophy of Ernst Bloch Culture

SHS Web of Conferences 72, 03002 (2019) https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf /20197203002 APPSCONF-2 019 Loneliness of human in the philosophy of Ernst Bloch culture Pavel Lyashenko 1, and Maxim Lyashchenko 1 1Orenburg State University, 460018, Orenburg, Russia Abstract. The problem of loneliness from the view point of philosophical and anthropological knowledge acquires special significance, is filled with new content in connection with the unfolding of the modern society transformation processes, as a result, with a new stage in the reappraisal of the modern culture utopian consciousness. At the same time, Ernst Bloch's culture philosophy induce particular scientific interest, according to which the meaningful status of utopia is determined by the fact that it forms a certain ideal image of the human world, which is the space of culture as a whole. In this regard, the study of the loneliness phenomenon in Ernst Bloch culture philosophy allows us to identify the socio-cultural mechanisms of loneliness, as well as key factors in the development of modern society, leading the person to negation and the destruction of his being. 1 Introduction Like a lot of factors that form the everyday world of human, loneliness, culture, utopia belong to the phenomena of human being that are complex for scientific and philosophical comprehension. Turning to the theoretical heritage of the past and modern philosophical research leads to mutually exclusive judgments about loneliness, about culture, and about utopia. Sometimes we come to the idea of the incompatibility of these phenomena, in the absence of any strong and stable connection between them. -

Chapter 5. Between Gleichschaltung and Revolution

Chapter 5 BETWEEN GLEICHSCHALTUNG AND REVOLUTION In the summer of 1935, as part of the Germany-wide “Reich Athletic Com- petition,” citizens in the state of Schleswig-Holstein witnessed the following spectacle: On the fi rst Sunday of August propaganda performances and maneuvers took place in a number of cities. Th ey are supposed to reawaken the old mood of the “time of struggle.” In Kiel, SA men drove through the streets in trucks bearing … inscriptions against the Jews … and the Reaction. One [truck] carried a straw puppet hanging on a gallows, accompanied by a placard with the motto: “Th e gallows for Jews and the Reaction, wherever you hide we’ll soon fi nd you.”607 Other trucks bore slogans such as “Whether black or red, death to all enemies,” and “We are fi ghting against Jewry and Rome.”608 Bizarre tableau were enacted in the streets of towns around Germany. “In Schmiedeberg (in Silesia),” reported informants of the Social Democratic exile organization, the Sopade, “something completely out of the ordinary was presented on Sunday, 18 August.” A no- tice appeared in the town paper a week earlier with the announcement: “Reich competition of the SA. On Sunday at 11 a.m. in front of the Rathaus, Sturm 4 R 48 Schmiedeberg passes judgment on a criminal against the state.” On the appointed day, a large crowd gathered to watch the spectacle. Th e Sopade agent gave the setup: “A Nazi newspaper seller has been attacked by a Marxist mob. In the ensuing melee, the Marxists set up a barricade. -

The Futurist Moment : Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture

MARJORIE PERLOFF Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO AND LONDON FUTURIST Marjorie Perloff is professor of English and comparative literature at Stanford University. She is the author of many articles and books, including The Dance of the Intellect: Studies in the Poetry of the Pound Tradition and The Poetics of Indeterminacy: Rimbaud to Cage. Published with the assistance of the J. Paul Getty Trust Permission to quote from the following sources is gratefully acknowledged: Ezra Pound, Personae. Copyright 1926 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, Collected Early Poems. Copyright 1976 by the Trustees of the Ezra Pound Literary Property Trust. All rights reserved. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, The Cantos of Ezra Pound. Copyright 1934, 1948, 1956 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Blaise Cendrars, Selected Writings. Copyright 1962, 1966 by Walter Albert. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1986 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1986 Printed in the United States of America 95 94 93 92 91 90 89 88 87 86 54321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Perloff, Marjorie. The futurist moment. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Futurism. 2. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Title. NX600.F8P46 1986 700'. 94 86-3147 ISBN 0-226-65731-0 For DAVID ANTIN CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xiii Preface xvii 1. -

Woottonbrookwombourne

WoottonbrookWOMBOURNE A beautiful collection of 1,2,3 & 4 bedroom homes and apartments 1 ith idyllic streets, quaint houses and handy shops, Wif you’re looking to relocate, Wombourne makes for an attractive and welcoming place. With its three main streets around a village green, it’s a beautiful South Staffordshire gem, with a quirky reputation for claiming to be England’s largest village. Just four miles from Wolverhampton, you won’t be short on things to do. Surrounded by countryside, it’s a rambler’s paradise. There’s the scenic Wom Brook walk or a Sunday afternoon amble up and down the South Staffs Railway Walk. There’s also Baggeridge Country Park, a mere 2.5 miles away by car. If it’s jogging, cycling or even fishing, you have the Staffordshire and Worcestershire canal on your Country Life doorstep too. Woottonbrook by Elan Homes is nestled in a quiet, rural location only five minutes away from Wombourne village. A mixture of bright, spacious and contemporary 1,2,3 & 4 bedroom homes and apartments effortlessly blends rural and urban life. Welcome to your future. 2 A lot of love goes into the building of an Elan home - and it shows. We lavish attention on the beautifully crafted, traditionally styled exterior so that you don’t just end up with any new home, but one of outstanding style and real character. Then, inside, we spread the love a little bit more, by creating highly contemporary living spaces that are simply a pleasure to live in. Offering light, airy, high specification, luxury accommodation that has the flexibility to be tailored to the individual wants and needs of you and your family. -

Did Anthropogeology Anticipate the Idea of the Anthropocene?

ANR0010.1177/2053019617742169The Anthropocene ReviewHäusler 742169research-article2017 Review The Anthropocene Review 1 –18 Did anthropogeology anticipate © The Author(s) 2017 Reprints and permissions: the idea of the Anthropocene? sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav https://doi.org/10.1177/2053019617742169DOI: 10.1177/2053019617742169 journals.sagepub.com/home/anr Hermann Häusler Abstract The term anthropogeology was coined in 1959 by the Austrian geologist Heinrich Häusler. It was taken up by the Swiss geologist Heinrich Jäckli in 1972, and independently introduced again by the German geologist Rudolf Hohl in 1974. Their concept aimed at mitigating humankind’s geotechnical and ecological impact in the dimension of endogenic and exogenic geologic processes. In that context anthropogeology was defined as the scientific discipline of applied geology integrating sectors of geosciences, geography, juridical, political and economic sciences as well as sectors of engineering sciences. In 1979 the German geologist Werner Kasig newly defined anthropogeology as human dependency on geologic conditions, in particular focusing on building stone, aggregates, groundwater and mineral resources. The severe problems of environmental pollution since the 1980s and the political relevance of environmental protection led to the initiation of the discipline ‘environmental geosciences’, which – in contrast to anthropogeology – was and is taught at universities worldwide. Keywords Anthropocene, anthropogeology, engineering geology, environmental geology, mankind as geologic factor, prognosis, shift of paradigm, stakeholder The roots of anthropogeology: Humankind as a geologic factor Since the 1850s a number of scientists have become aware of the important role of humans in the present geologic cycle, and termed humankind as a geological and geomorphological force (Hamilton and Grinevald, 2015; Häusler Jr, 2016; Lewis and Maslin, 2015; Lowenthal, 2016, Steffen et al., 2007; Trachtenberg, 2015; Zalasiewicz et al., 2011). -

Philosophy of Science -----Paulk

PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE -----PAULK. FEYERABEND----- However, it has also a quite decisive role in building the new science and in defending new theories against their well-entrenched predecessors. For example, this philosophy plays a most important part in the arguments about the Copernican system, in the development of optics, and in the Philosophy ofScience: A Subject with construction of a new and non-Aristotelian dynamics. Almost every work of Galileo is a mixture of philosophical, mathematical, and physical prin~ a Great Past ciples which collaborate intimately without giving the impression of in coherence. This is the heroic time of the scientific philosophy. The new philosophy is not content just to mirror a science that develops independ ently of it; nor is it so distant as to deal just with alternative philosophies. It plays an essential role in building up the new science that was to replace 1. While it should be possible, in a free society, to introduce, to ex the earlier doctrines.1 pound, to make propaganda for any subject, however absurd and however 3. Now it is interesting to see how this active and critical philosophy is immoral, to publish books and articles, to give lectures on any topic, it gradually replaced by a more conservative creed, how the new creed gener must also be possible to examine what is being expounded by reference, ates technical problems of its own which are in no way related to specific not to the internal standards of the subject (which may be but the method scientific problems (Hurne), and how there arises a special subject that according to which a particular madness is being pursued), but to stan codifies science without acting back on it (Kant). -

Discovering the Lost Race Story: Writing Science Fiction, Writing Temporality

Discovering the Lost Race Story: Writing Science Fiction, Writing Temporality This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia 2008 Karen Peta Hall Bachelor of Arts (Honours) Discipline of English and Cultural Studies School of Social and Cultural Studies ii Abstract Genres are constituted, implicitly and explicitly, through their construction of the past. Genres continually reconstitute themselves, as authors, producers and, most importantly, readers situate texts in relation to one another; each text implies a reader who will locate the text on a spectrum of previously developed generic characteristics. Though science fiction appears to be a genre concerned with the future, I argue that the persistent presence of lost race stories – where the contemporary world and groups of people thought to exist only in the past intersect – in science fiction demonstrates that the past is crucial in the operation of the genre. By tracing the origins and evolution of the lost race story from late nineteenth-century novels through the early twentieth-century American pulp science fiction magazines to novel-length narratives, and narrative series, at the end of the twentieth century, this thesis shows how the consistent presence, and varied uses, of lost race stories in science fiction complicates previous critical narratives of the history and definitions of science fiction. In examining the implicit and explicit aspects of temporality and genre, this thesis works through close readings of exemplar texts as well as historicist, structural and theoretically informed readings. It focuses particularly on women writers, thus extending previous accounts of women’s participation in science fiction and demonstrating that gender inflects constructions of authority, genre and temporality. -

Specialists, Spies, “Special Settlers”, and Prisoners of War: Social Frictions in the Kuzbass (USSR), 1920–1950

IRSH 60 (2015), Special Issue, pp. 185–205 doi:10.1017/S0020859015000462 © 2015 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Specialists, Spies, “Special Settlers”, and Prisoners of War: Social Frictions in the Kuzbass (USSR), 1920–1950 J ULIA L ANDAU Buchenwald Memorial 99427 Weimar-Buchenwald, Germany E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: The Kuzbass coalmining region in western Siberia (Kuznetsk Basin) was explored, populated, and exploited under Stalin’s rule. Struggling to offset a high labour turnover, the local state-run coal company enrolled deportees from other regions of Russia and Siberia, who were controlled by the secret police (OGPU). These workers shared a common experience in having been forcibly separated from their place of origin. At the same time, foreigners were recruited from abroad as experts and offered a privileged position. In the years of the Great Terror (1936−1938) both groups were persecuted, as they were regarded by the state as disloyal and suspicious. After the war, foreigners were recruited in large numbers as prisoners of war. Thus, migrants, foreigners, and deportees from other regions and countries constituted a significant part of the workforce in the Kuzbass, while their status constantly shifted due to economic needs and repressive politics. From the beginning of the twentieth century, after the building of the Trans- Siberian Railway, the economic resources of Siberia became the subject of political consideration and planning efforts by the Russian and later the Soviet state. The Kuzbass region in western Siberia amazed Soviet planners with its vast supply of very high-quality coal – the layers of coal measuring from 1.5 to 20 metres.1 The content of ash (about 10 per cent) and sulphur (between 0.4 and 0.7 per cent) was comparatively low. -

Picturing France

Picturing France Classroom Guide VISUAL ARTS PHOTOGRAPHY ORIENTATION ART APPRECIATION STUDIO Traveling around France SOCIAL STUDIES Seeing Time and Pl ace Introduction to Color CULTURE / HISTORY PARIS GEOGRAPHY PaintingStyles GOVERNMENT / CIVICS Paris by Night Private Inve stigation LITERATURELANGUAGE / CRITICISM ARTS Casual and Formal Composition Modernizing Paris SPEAKING / WRITING Department Stores FRENCH LANGUAGE Haute Couture FONTAINEBLEAU Focus and Mo vement Painters, Politics, an d Parks MUSIC / DANCENATURAL / DRAMA SCIENCE I y Fontainebleau MATH Into the Forest ATreebyAnyOther Nam e Photograph or Painting, M. Pa scal? ÎLE-DE-FRANCE A Fore st Outing Think L ike a Salon Juror Form Your Own Ava nt-Garde The Flo ating Studio AUVERGNE/ On the River FRANCHE-COMTÉ Stream of Con sciousness Cheese! Mountains of Fra nce Volcanoes in France? NORMANDY “I Cannot Pain tan Angel” Writing en Plein Air Culture Clash Do-It-Yourself Pointillist Painting BRITTANY Comparing Two Studie s Wish You W ere Here Synthétisme Creating a Moo d Celtic Culture PROVENCE Dressing the Part Regional Still Life Color and Emo tion Expressive Marks Color Collectio n Japanese Prin ts Legend o f the Château Noir The Mistral REVIEW Winds Worldwide Poster Puzzle Travelby Clue Picturing France Classroom Guide NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON page ii This Classroom Guide is a component of the Picturing France teaching packet. © 2008 Board of Trustees of the National Gallery of Art, Washington Prepared by the Division of Education, with contributions by Robyn Asleson, Elsa Bénard, Carla Brenner, Sarah Diallo, Rachel Goldberg, Leo Kasun, Amy Lewis, Donna Mann, Marjorie McMahon, Lisa Meyerowitz, Barbara Moore, Rachel Richards, Jennifer Riddell, and Paige Simpson. -

Geologic Map of the Victoria Quadrangle (H02), Mercury

H01 - Borealis Geologic Map of the Victoria Quadrangle (H02), Mercury 60° Geologic Units Borea 65° Smooth plains material 1 1 2 3 4 1,5 sp H05 - Hokusai H04 - Raditladi H03 - Shakespeare H02 - Victoria Smooth and sparsely cratered planar surfaces confined to pools found within crater materials. Galluzzi V. , Guzzetta L. , Ferranti L. , Di Achille G. , Rothery D. A. , Palumbo P. 30° Apollonia Liguria Caduceata Aurora Smooth plains material–northern spn Smooth and sparsely cratered planar surfaces confined to the high-northern latitudes. 1 INAF, Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Rome, Italy; 22.5° Intermediate plains material 2 H10 - Derain H09 - Eminescu H08 - Tolstoj H07 - Beethoven H06 - Kuiper imp DiSTAR, Università degli Studi di Napoli "Federico II", Naples, Italy; 0° Pieria Solitudo Criophori Phoethontas Solitudo Lycaonis Tricrena Smooth undulating to planar surfaces, more densely cratered than the smooth plains. 3 INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Teramo, Teramo, Italy; -22.5° Intercrater plains material 4 72° 144° 216° 288° icp 2 Department of Physical Sciences, The Open University, Milton Keynes, UK; ° Rough or gently rolling, densely cratered surfaces, encompassing also distal crater materials. 70 60 H14 - Debussy H13 - Neruda H12 - Michelangelo H11 - Discovery ° 5 3 270° 300° 330° 0° 30° spn Dipartimento di Scienze e Tecnologie, Università degli Studi di Napoli "Parthenope", Naples, Italy. Cyllene Solitudo Persephones Solitudo Promethei Solitudo Hermae -30° Trismegisti -65° 90° 270° Crater Materials icp H15 - Bach Australia Crater material–well preserved cfs -60° c3 180° Fresh craters with a sharp rim, textured ejecta blanket and pristine or sparsely cratered floor. 2 1:3,000,000 ° c2 80° 350 Crater material–degraded c2 spn M c3 Degraded craters with a subdued rim and a moderately cratered smooth to hummocky floor.