The Gould Variations: Technology, Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Howard Dyck Reflects on Glenn Gould's The

“What you intended to say”: Howard Dyck Reflects on Glenn Gould’s The Quiet in the Land Doreen Helen Klassen The Quiet in the Land is a radio documentary by Canadian pianist and composer Glenn Gould (1932-82) that features the voices of nine Mennonite musicians and theologians who reflect on their Mennonite identity as a people that are in the world yet separate from it. Like the other radio compositions in his The Solitude Trilogy—“The Idea of North” (1967) and “The Latecomers” (1969)—this work focuses on those who, either through geography, history, or ideology, engage in a “deliberate withdrawal from the world.”1 Based on Gould’s interviews in Winnipeg in July 1971, The Quiet in the Land was released by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) only in 1977, as Gould awaited changes in technology that would allow him to weave together snatches of these interviews thematically. His five primary themes were separateness, dealing with an increasingly urban and cosmopolitan lifestyle, the balance between evangelism and isolation, concern with others’ well-being in relation to the historic peace position, and maintaining Mennonite unity in the midst of fissions.2 He contextualized the documentary ideologically and sonically by placing it within the soundscape of a church service recorded at Waterloo-Kitchener United Mennonite Church in Waterloo, Ontario.3 Knowing that the work had received controversial responses from Mennonites upon its release, I framed my questions to former CBC radio producer Howard Dyck,4 one of Gould’s interviewees and later one of his 1 Bradley Lehman, “Review of Glenn Gould’s ‘The Quiet in the Land,’” www. -

American Masters 200 List Finaljan2014

Premiere Date # American Masters Program Title (Month-YY) Subject Name 1 ARTHUR MILLER: PRIVATE CONVERSATIONS On the Set of "Death of a Salesman" June-86 Arthur Miller 2 PHILIP JOHNSON: A SELF PORTRAIT June-86 Philip Johnson 3 KATHERINE ANNE PORTER: THE EYE OF MEMORY July-86 Katherine Anne Porter 4 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 1) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 5 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 2) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 6 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 3) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 7 BILLIE HOLIDAY: THE LONG NIGHT OF LADY DAY August-86 Billie Holiday 8 JAMES LEVINE: THE LIFE IN MUSIC August-86 James Levine 9 AARON COPLAND: A SELF PORTRAIT August-86 Aaron Copland 10 THOMAS EAKINS: A MOTION PORTRAIT August-86 Thomas Eakins 11 GEORGIA O'KEEFFE September-86 Georgia O'Keeffe 12 EUGENE O'NEILL: A GLORY OF GHOSTS September-86 Eugene O'Neill 13 ISAAC IN AMERICA: A JOURNEY WITH ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER July-87 Isaac Bashevis Singer 14 DIRECTED BY WILLIAM WYLER July-87 William Wyler 15 ARTHUR RUBENSTEIN: RUBENSTEIN REMEMBERED July-87 Arthur Rubinstein 16 ALWIN NIKOLAIS AND MURRAY LOUIS: NIK AND MURRAY July-87 Alwin Nikolais/Murray Louis 17 GEORGE GERSHWIN REMEMBERED August-87 George Gershwin 18 MAURICE SENDAK: MON CHER PAPA August-87 Maurice Sendak 19 THE NEGRO ENSEMBLE COMPANY September-87 Negro Ensemble Co. 20 UNANSWERED PRAYERS: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF TRUMAN CAPOTE September-87 Truman Capote 21 THE TEN YEAR LUNCH: THE WIT AND LEGEND OF THE ALGONQUIN ROUND TABLE September-87 Algonquin Round Table 22 BUSTER KEATON: A HARD ACT TO FOLLOW (Part 1) November-87 Buster Keaton 23 BUSTER KEATON: -

American Academy of Arts and Letters

NEWS RELEASE American Academy of Arts and Letters Contact: Ardith Holmgrain 633 WEST 155 STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10032 [email protected] www.artsandletters.org (212) 368-5900 http://www.artsandletters.org/press_releases/2010music.php THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND LETTERS ANNOUNCES 2010 MUSIC AWARD WINNERS Sixteen Composers Receive Awards Totaling $170,000 New York, March 4, 2010—The American Academy of Arts and Letters announced today the sixteen recipients of this year's awards in music, which total $170,000. The winners were selected by a committee of Academy members: Robert Beaser (chairman), Bernard Rands, Gunther Schuller, Steven Stucky, and Yehudi Wyner. The awards will be presented at the Academy's annual Ceremonial in May. Candidates for music awards are nominated by the 250 members of the Academy. ACADEMY AWARDS IN MUSIC Four composers will each receive a $7500 Academy Award in Music, which honors outstanding artistic achievement and acknowledges the composer who has arrived at his or her own voice. Each will receive an additional $7500 toward the recording of one work. The winners are Daniel Asia, David Felder, Pierre Jalbert, and James Primosch. WLADIMIR AND RHODA LAKOND AWARD The Wladimir and Rhoda Lakond award of $10,000 is given to a promising mid-career composer. This year the award will go to James Lee III. GODDARD LIEBERSON FELLOWSHIPS Two Goddard Lieberson fellowships of $15,000, endowed in 1978 by the CBS Foundation, are given to mid-career composers of exceptional gifts. This year they will go to Philippe Bodin and Aaron J. Travers. WALTER HINRICHSEN AWARD Paula Matthusen will receive the Walter Hinrichsen Award for the publication of a work by a gifted composer. -

David Dubal Tem Dado Recitais De Piano E Masterclasses Em Todo O

David Dubal tem dado recitais de piano e masterclasses em todo o mundo, e foi jurado de competições internacionais de piano (incluindo o Van Cliburn International Piano Competition). Ele gravou vários CDs em conjunto com o pianista Stanley Waldoff para a gravadora Musical Heritage Society, e três discos foram remasterizados e lançados em CD pela gravadora Arkiv. Em 2013, Dubal participou do filme Holandês Nostalgia: a Música de Wim Statius Müller, comentando sobre as músicas do compositor, o qual foi seu professor em Ohio. Dubal lecionou na Juilliard School de 1983 a 2018, e na Manhattan School of Music de 1994 a 2015. Dubal escreveu vários livros, incluindo a Arte do Piano, Noites com Horowitz, Conversas com Menuhin, Reflexões do Teclado, Conversas com João Carlos Martins, Lembrando Horowitz e O Essencial Cânone da Música Clássica (um guia enciclopédico dos compositores proeminentes). Ele também escreveu e apresentou o documentário A Era Dourada do Piano, premiado com um Emmy e produzido por Peter Rosen. Dubal dá palestras semanais, Noites com Piano, na Good Shepherd-Faith Presbyterian Church, em Nova Iorque. Ele deu inúmeras palestras no Metropolitan Museum of Art sobre os grandes pianistas, mudanças sociais, história da música e tradição do piano. Suas palestras estão disponíveis em seu site: https://www.pianoevenings.com/david-dubal. Dubal é o anfitrião das palestras Sobre o Piano, um programa de performances comparativas de piano na WWFM e o anfitrião de Reflexões do Teclado, uma exploração semanal de gravações de piano, produzido na WQXR-FM. No final da década de 1990, ele apresentou uma série de programas de rádio intitulado The American Century, com foco em obras musicais de compositores Americanos do século XX, agora disponíveis no YouTube. -

Catalog of Copyright Entries 3D Ser Vol 27 Pt

' , S^ L* 'i-\ "'M .<^^°^ o. %-o^' .:-iM^ %/ :>m^^%,^' .^•^ °- .^il& >^'^^ "• "^^ ^^'^ 'ij : %.** -^^^^^^ -^K^ ^'-^ ° /\ A '5.^ .*^ .*^ iO. A- -> °o C^ °^ ' ./v ,0^ t>.~ « .^' '>> %.,.' ,v^:<'^, %/ These entries alone may not reflect the complete Copyright Office record pertaining to a particular work. Contact the U.S. Copyright Office for information about any additional records that may exist. ' .. .0^ o r- o > J i' <>> «, '(\'?s^/,*o 'tis 'V' ^/i^ratfete' *> «. *i%^^/, * %^-m--/ %-w--/ \w\.** %/W--/ %--W^,-^~ ^#/V* W> aV -^a r* ^^''' "^^^ ^^^ "^^^ '^^^ i^ "fc '^^ ^S^'' -^ ^- ^^ These entries alone may not reflect the complete Copyright Office record pertaining to a particular work. Contact the U.S. Copyright Office for information about any additional records that may exist. These entries alone may not reflect the complete Copyright Office record pertaining to a particular work. Contact the U.S. Copyright Office for information about any additional records that may exist. a particular These entries alone may not reflect the complete Copyright Office record pertaining to work. Contact the U.S. Copyright Office for information about any additional records that may exist. These entries alone may not reflect the complete Copyright Office record pertaining to a particular work. Contact the U.S. Copyright Office for information about any additional records that may exist. ISSN 0041-7823 Catalog of Copyright Entries: Third Series Volume 27, Part iiB Commercial Prints and Labels January—December 1973 •^ ,t«s COPYRIGHT OFFICE • THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON : 1974 These entries alone may not reflect the complete Copyright Office record pertaining to a particular work. Contact the U.S. Copyright Office for information about any additional records that may exist. -

The Pianist's Freedom and the Work's Constrictions

The Pianist’s Freedom and the Work’s Constrictions What Tempo Fluctuation in Bach and Chopin Indicate Alisa Yuko Bernhard A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music (Performance) Sydney Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney 2017 Declaration I declare that the research presented here is my own original work and has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of a degree. Alisa Yuko Bernhard 10 November 2016 i Abstract The concept of the musical work has triggered much discussion: it has been defined and redefined, and at times attacked and deconstructed, by writers including Wolterstorff, Goodman, Levinson, Davies, Nattiez, Goehr, Abbate and Parmer, to name but a few. More often than not, it is treated either as an abstract sound-structure or, in contrast, as a culturally constructed concept, even a chimera. But what is a musical work to the performer, actively engaged in a “relationship” with the work he or she is interpreting? This question, not asked often enough in scholarship, can be used to yield fascinating insights into the ontological status of the work. My thesis therefore explores the relationship between the musical work and the performance, with a specific focus on classical pianists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. I make use of two methodological starting-points for considering the nature of the work. Firstly, I survey what pianists have said and written in interviews and biographies regarding their role as interpreters of works. Secondly, I analyse pianists’ use of tempo fluctuation at structurally significant moments in a selection of pieces by Johann Sebastian Bach and Frederic Chopin. -

Gould's Notes on Bach's Goldberg Variations by Glenn Gould Copyright/Source

32 Short Films About Glenn Gould (1993), a film directed by François GIRARD and written by Girard with Don MCKELLAR, offers 32 biographical insights into the life of Canadian pianist Glenn GOULD. Non-linear in its construction, the film is made up of 32 segments, each of which explains a facet of Gould's complex interior life (the title refers to the number of the Goldberg Variations, Gould's most famous interpretation). Gould's odd relationships with friends, his obsession with long phone calls, his ideas about music and the human voice are just a few of the themes dealt with in the film. Several segments deal with his celebrated 1967 radio documentary, The Idea of the North. Another sequence attempts to reconstruct the abstract symphony of human and mechanical sound as it might have struck Gould when he entered a truck stop on the edge of Toronto, a concept of sound and music that was central to Gould's radio work. One of the "short films" is an animated piece by Norman MCLAREN with Gould's piano playing on the soundtrack. 32 Short Films marked a shift in style for Canada's semi-commercial cinema. Although Canadian filmmakers David CRONENBERG, Atom EGOYAN and Patricia ROZEMA had gained significant international attention during the 1980s and early 1990s, 32 Short Films departed from the narrative strategy of these filmmakers and turned instead to Canada's rich tradition of EXPERIMENTAL FILM and video for its inspiration. Experimental filmmaker Arthur Lipsett's innovative assembly of film fragments may have influenced the structure of Girard's film, while Michael SNOW's minimalism could have inspired the sequence in 32 Short Films composed only of extreme close-ups of piano hammers hitting the strings. -

Культура І Мистецтво Великої Британії Culture and Art of Great Britain

НАЦІОНАЛЬНА АКАДЕМІЯ ПЕДАГОГІЧНИХ НАУК УКРАЇНИ ІНСТИТУТ ПЕДАГОГІКИ Т.К. Полонська КУЛЬТУРА І МИСТЕЦТВО ВЕЛИКОЇ БРИТАНІЇ CULTURE AND ART OF GREAT BRITAIN Навчальний посібник елективного курсу з англійської мови для учнів старших класів профільної школи Київ Видавничий дім «Сам» 2017 УДК 811.111+930.85(410)](076.6) П 19 Рекомендовано до друку вченою радою Інституту педагогіки НАПН України (протокол №11 від 08.12.2016 року) Схвалено для використання у загальноосвітніх навчальних закладах (лист ДНУ «Інститут модернізації змісту освіти». №21.1/12 -Г-233 від 15.06.2017 року) Рецензенти: Олена Ігорівна Локшина – доктор педагогічних наук, професор, завідувачка відділу порівняльної педагогіки Інституту педагогіки НАПН України; Світлана Володимирівна Соколовська – кандидат педагогічних наук, доцент, заступник декана з науково- методичної та навчальної роботи факультету права і міжнародних відносин Київського університету імені Бориса Грінченка; Галина Василівна Степанчук – учителька англійської мови Навчально-виховного комплексу «Нововолинська спеціалізована школа І–ІІІ ступенів №1 – колегіум» Нововолинської міської ради Волинської області. Культура і мистецтво Великої Британії : навчальний посібник елективного курсу з англійської мови для учнів старших класів профільної школи / Т. К. Полонська. – К. : Видавничий дім «Сам», 2017. – 96 с. ISBN Навчальний посібник є основним засобом оволодіння учнями старшої школи змістом англомовного елективного курсу «Культура і мистецтво Великої Британії». Створення посібника сприятиме подальшому розвиткові у -

West Side Story” (Original Cast Recording) (1957) Added to the National Registry: 2008 Essay by Robert L

“West Side Story” (Original cast recording) (1957) Added to the National Registry: 2008 Essay by Robert L. McLaughlin (guest essay)* Original “West Side Story” cast members at recording session (from left: Elizabeth Taylor, Carmen Gutierrez, Marilyn Cooper, Carol Lawrence) “West Side Story” is among the best and most important of Broadway musicals. It was both a culmination of the Rodgers and Hammerstein integrated musical, bringing together music, dance, language and design in service of a powerful narrative, and an arrow pointing toward the future, creating new possibilities for what a musical can be and how it can work. Its cast recording preserves its score and the original performances. “West Side Story’s” journey to theater immortality was not easy. The show’s origins came in the late 1940s when director/choreographer Jerome Robbins, composer Leonard Bernstein, and playwright Arthur Laurents imagined an updated retelling of “Romeo and Juliet,” with the star- crossed lovers thwarted by their contentious Catholic and Jewish families. After some work, the men decided that such a musical would evoke “Abie’s Irish Rose” more than Shakespeare and so they set the project aside. A few years later, however, Bernstein and Laurents were struck by news reports of gang violence in New York and, with Robbins, reconceived the piece as a story of two lovers set against Caucasian and Puerto Rican gang warfare. The musical’s “Prologue” establishes the rivalry between the Jets, a gang of white teens, children mostly of immigrant parents and claimants of a block of turf on New York City’s west side, and the Sharks, a gang of Puerto Rican teens, recently come to the city and, as the play begins, finally numerous enough to challenge the Jets’ dominion. -

Media Coverage

Teaching the Life of Music MEDIA COVERAGE Filmblanc, 1121 Bay St., Suite 1901- Toronto, Ontario- Canada –M5S 3L9, www.filmblanc.com Five Worth Watching on Sunday The Toronto Star/ thestar.com Debra Yeo January 20, 2012 Print/Online Mention Link: http://www.thestar.com/article/1118955--five-worth-watching-on-sunday Music to the Soul: El Sistema has reached more than 350,000 children since it was founded 36 years ago in Venezuela as a way to counteract poverty and violence through music education. The documentary Teaching the Life of Music looks at the program’s impact in Canada, the U.S. and Scotland, where El Sistema’s goals have been applied to local kids and communities. Calgary-born, Victoria-raised Cory Monteith (Finn on Glee) narrates (OMNI at 9). Documentary brings music to the masses Insidetoronto.com Justin Skinner January 21, 2012 Online Interviews/photo Link: http://www.insidetoronto.com/what_s%20on/article/1283121--documentary-brings- music-to-the-masses Documentary brings music to the masses Downtown residents turn camera on El Sistema Teaching for Life. Founder of El Sistema, Maestro Jose Antonio Abreu is joined by the three kids – Peter, left, Pegless and Daniella – featured in the documentary film Teaching the Life of Music. From its humble roots in Venezuela to its latest incarnation in Toronto, El Sistema has helped hundreds of thousands of children enrich their lives through music. The organization, founded in 1975 by Maestro Jose Antonio Abreu, helps at-risk children find a positive outlet and uses music to help them develop in various ways. -

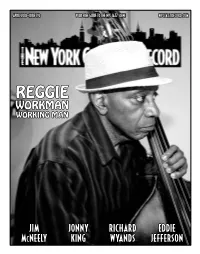

Reggie Workman Working Man

APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM REGGIE WORKMAN WORKING MAN JIM JONNY RICHARD EDDIE McNEELY KING WYANDS JEFFERSON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JIM Mcneely 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JONNY KING 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : REGGIE WORKMAN 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : RICHARD WYANDS by marilyn lester Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest WE Forget : EDDIE JEFFERSON 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : MINUS ZERO by george grella US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviews 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne -

1. Early Years: Maria Before La Callas 2. Metamorphosis

! 1. EARLY YEARS: MARIA BEFORE LA CALLAS Maria Callas was born in New York on 2nd December 1923, the daughter of Greek parents. Her name at birth was Maria Kalogeropoulou. When she was 13 years old, her parents separated. Her mother, who was ambitious for her daughter’s musical talent, took Maria and her elder sister to live in Athens. There Maria made her operatic debut at the age of just 15 and studied with Elvira de Hidalgo, a Spanish soprano who had sung with Enrico Caruso. Maria, an intensely dedicated student, began to develop her extraordinary potential. During the War years in Athens the young soprano sang such demanding operatic roles as Tosca and Leonore in Beethoven’s Fidelio. In 1945, Maria returned to the USA. She was chosen to sing Turandot for the inauguration of a prestigious new opera company in Chicago, but it went bankrupt before the opening night. Yet fate turned out to be on Maria’s side: she had been spotted by the veteran Italian tenor, Giovanni Zenatello, a talent scout for the opera festival at the Verona Arena. Callas made her Italian debut there in 1947, starring in La Gioconda by Ponchielli. Her conductor, Tullio Serafin, was to become a decisive force in her career. 2. METAMORPHOSIS After Callas’ debut at the Verona Arena, she settled in Italy and married a wealthy businessman, Giovanni Battista Meneghini. Her influential conductor from Verona, Tullio Serafin, became her musical mentor. She began to make her name in grand roles such as Turandot, Aida, Norma – and even Wagner’s Isolde and Brünnhilde – but new doors opened for her in 1949 when, at La Fenice opera house in Venice, she replaced a famous soprano in the delicate, florid role of Elvira in Bellini’s I puritani.