BJR.Kingdavid.June2016.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Most Contagious 2011

MOST CONTAGIOUS 2011 Cover image: Take This LoLLipop / Jason Zada most contagious / p.02 / mosT ConTAGIOUS 2011 / subsCripTion oFFer / 20% disCounT FuTure-prooFing your brain VALid unTiL 9Th JANUARY 2012 offering a saving of £200 gBP chapters / Contagious exists to find and filter the most innovative 01 / exercises in branding, technology, and popular culture, and movemenTs deliver this collective wisdom to our beloved subscribers. 02 / Once a year, we round up the highlights, identify what’s important proJeCTs and why, and push it out to the world, for free. 03 / serviCe Welcome to Most Contagious 2011, the only retrospective you’ll ever need. 04 / soCiaL It’s been an extraordinary year; economies in turmoil, empires 05 / torn down, dizzying technological progress, the evolution of idenTiTy brands into venture capitalists, the evolution of a generation of young people into entrepreneurs… 06 / TeChnoLogy It’s also been a bumper year for the Contagious crew. Our 07 / Insider consultancy division is now bringing insight and inspiration daTa to clients from Kraft to Nike, and Google to BBC Worldwide. We 08 / were thrilled with the success of our first Now / Next / Why event augmenTed in London in December, and are bringing the show to New York 09 / on February 22nd. Grab your ticket here. money We’ve added more people to our offices in London and New 10 / York, launched an office in India, and in 2012 have our sights haCk Culture firmly set on Brazil. Latin America, we’re on our way. Get ready! 11 / musiC 2.0 We would also like to take this opportunity to thank our friends, supporters and especially our valued subscribers, all over the 12 / world. -

Woman War Correspondent,” 1846-1945

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository CONDITIONS OF ACCEPTANCE: THE UNITED STATES MILITARY, THE PRESS, AND THE “WOMAN WAR CORRESPONDENT,” 1846-1945 Carolyn M. Edy A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Jean Folkerts W. Fitzhugh Brundage Jacquelyn Dowd Hall Frank E. Fee, Jr. Barbara Friedman ©2012 Carolyn Martindale Edy ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract CAROLYN M. EDY: Conditions of Acceptance: The United States Military, the Press, and the “Woman War Correspondent,” 1846-1945 (Under the direction of Jean Folkerts) This dissertation chronicles the history of American women who worked as war correspondents through the end of World War II, demonstrating the ways the military, the press, and women themselves constructed categories for war reporting that promoted and prevented women’s access to war: the “war correspondent,” who covered war-related news, and the “woman war correspondent,” who covered the woman’s angle of war. As the first study to examine these concepts, from their emergence in the press through their use in military directives, this dissertation relies upon a variety of sources to consider the roles and influences, not only of the women who worked as war correspondents but of the individuals and institutions surrounding their work. Nineteenth and early 20th century newspapers continually featured the woman war correspondent—often as the first or only of her kind, even as they wrote about more than sixty such women by 1914. -

The Origins of Hamas: Militant Legacy Or Israeli Tool?

THE ORIGINS OF HAMAS: MILITANT LEGACY OR ISRAELI TOOL? JEAN-PIERRE FILIU Since its creation in 1987, Hamas has been at the forefront of armed resistance in the occupied Palestinian territories. While the move- ment itself claims an unbroken militancy in Palestine dating back to 1935, others credit post-1967 maneuvers of Israeli Intelligence for its establishment. This article, in assessing these opposing nar- ratives and offering its own interpretation, delves into the historical foundations of Hamas starting with the establishment in 1946 of the Gaza branch of the Muslim Brotherhood (the mother organization) and ending with its emergence as a distinct entity at the outbreak of the !rst intifada. Particular emphasis is given to the Brotherhood’s pre-1987 record of militancy in the Strip, and on the complicated and intertwining relationship between the Brotherhood and Fatah. HAMAS,1 FOUNDED IN the Gaza Strip in December 1987, has been the sub- ject of numerous studies, articles, and analyses,2 particularly since its victory in the Palestinian legislative elections of January 2006 and its takeover of Gaza in June 2007. Yet despite this, little academic atten- tion has been paid to the historical foundations of the movement, which grew out of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Gaza branch established in 1946. Meanwhile, two contradictory interpretations of the movement’s origins are in wide circulation. The !rst portrays Hamas as heir to a militant lineage, rigorously inde- pendent of all Arab regimes, including Egypt, and harking back to ‘Izz al-Din al-Qassam,3 a Syrian cleric killed in 1935 while !ghting the British in Palestine. -

An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem Ardi Imseis

American University International Law Review Volume 15 | Issue 5 Article 2 2000 Facts on the Ground: An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem Ardi Imseis Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Imseis, Ardi. "Facts on the Ground: An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem." American University International Law Review 15, no. 5 (2000): 1039-1069. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FACTS ON THE GROUND: AN EXAMINATION OF ISRAELI MUNICIPAL POLICY IN EAST JERUSALEM ARDI IMSEIS* INTRODUCTION ............................................. 1040 I. BACKGROUND ........................................... 1043 A. ISRAELI LAW, INTERNATIONAL LAW AND EAST JERUSALEM SINCE 1967 ................................. 1043 B. ISRAELI MUNICIPAL POLICY IN EAST JERUSALEM ......... 1047 II. FACTS ON THE GROUND: ISRAELI MUNICIPAL ACTIVITY IN EAST JERUSALEM ........................ 1049 A. EXPROPRIATION OF PALESTINIAN LAND .................. 1050 B. THE IMPOSITION OF JEWISH SETTLEMENTS ............... 1052 C. ZONING PALESTINIAN LANDS AS "GREEN AREAS"..... -

How Foreign Correspondents Risked Capture, Torture and Death to Cover World War II by Ray Moseley

2017-042 12 May 2017 Reporting War: How Foreign Correspondents Risked Capture, Torture and Death to Cover World War II by Ray Moseley. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2017. Pp. xiii, 421. ISBN 978–0–300–22466–5. Review by Donald Lateiner, Ohio Wesleyan University ([email protected]). As a child, Ray Moseley listened to reporters of World War II on the radio. He later came to know fourteen of them, but they never spoke of their experiences and he never asked (xi)—a missed oppor- tunity many of us have experienced with the diminishing older generation. 1 Moseley himself was a war and foreign correspondent for forty years from 1961, so he knows the territory from the inside out. He was posted to Moscow, Berlin, Belgrade, and Cairo, among many newspaper datelines. His book is an account and tribute to mostly British and American reporters who told “the greatest story of all time” (1, unintended blasphemy?). 2 He does not include World War II photographers as such, 3 but offers photos taken of many reporters. As usual, the European theater gets fuller attention than the Pacific (17 of the book’s 22 chapters). By design, breadth of coverage here trumps depth.4 Moseley prints excerpts from British, Australian, Canadian, Soviet, South African, Danish, Swedish, French, and Italian reporters. He excludes Japanese and German correspondents because “no independent reporting was possible in those countries” (x). This is a shame, since a constant thread in the reports is the relentless, severe censorship in occupied countries, invaded and invading Allied authorities, and the American and British Armed Forces them- selves. -

Hamas Attack on Israel Aims to Capitalize on Palestinian

Selected articles concerning Israel, published weekly by Suburban Orthodox Toras Chaim’s (Baltimore) Israel Action Committee Edited by Jerry Appelbaum ( [email protected] ) | Founding editor: Sheldon J. Berman Z”L Issue 8 8 7 Volume 2 1 , Number 1 9 Parshias Bamidbar | 48th Day Omer May 1 5 , 2021 Hamas Attack on Israel Aims to Capitalize on Palestinian Frustration By Dov Lieber and Felicia Schwartz wsj.com May 12, 2021 It is not that the police caused the uptick in violence, forces by Monday evening from Shei kh Jarrah. The but they certainly ran headfirst, full - speed, guns forces were there as part of security measures surrounding blazing into the trap that was set for them. the nightly protests. When the secretive military chief of the Palestinian As the deadline passed, the group sent the barrage of Islamist movement Hamas emerged from the shadows last rockets toward Jerusalem, precipitating the Israeli week, he chose to weigh in on a land dispute in East response. Jerusalem, threatening to retaliate against Israel if Israeli strikes and Hamas rocket fire have k illed 56 Palestinian residents there were evicted from their homes. Palestinians, including 14 children, and seven Israelis, “If the aggression against our people…doesn’ t stop including one child, according to Palestinian and Israeli immediately,” warned the commander, Mohammad Deif, officials. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said Israel “the enemy will pay an expensive price.” has killed dozens of Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad Hamas followed through on the threat, firing from the operatives. Gaza Strip, which it governs, over a thousand rockets at Althou gh the Palestinian youth have lacked a single Israel since Monday evening. -

Moshe Dayan: Iconic Military Leader Moshe Dayan, with His Iconic Eye Patch, Became the Face of Israel’S Astonishing Six Day War

Educator’s Guide Moshe Dayan: Iconic Military Leader Moshe Dayan, with his iconic eye patch, became the face of Israel’s astonishing Six Day War. After leading Israel to victory in the 1956 Sinai Campaign, Dayan was appointed defense minister in 1967, ahead of the Six Day War, in order to assuage the public’s growing fear of annihilation. But what was Dayan’s role in the war itself? Why is he credited as the hero of the war, when Levi Eshkol was prime minister and Yitzhak Rabin was IDF chief-of-staff? What was his background and did his questionable private life dampen or heighten his heroic image? Video: https://unpacked.education/video/moshe-dayan-iconic-military-leader/ Further Reading 1. Mordechai Bar-On, Moshe Dayan: Israel’s Controversial Hero, Chapter 10 2. David K. Shipler, Moshe Dayan, 66, Dies in Israel; Hero of War, Architect of Peace, https://www.nytimes.com/1981/10/17/obituaries/moshe-dayan-66-dies-in-israel-hero -of-war-architect-of-peace.htm 3. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/moshe-dayan 4. Primary source - PM Levi Eshkol’s speech after the war, https://israeled.org/resources/documents/prime-minister-levi-eshkol-statement-kn esset-conclusion-june-war/ 5. Primary source - Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin’s speech after the war, https://israeled.org/resources/documents/israeli-chief-staff-yitzhak-rabin-right-israe l/ © 2019 Unpacked for Educators All Rights Reserved 1 Review - Did the students understand the material? 1. How did Moshe Dayan lose his eye? 2. With which historic 1967 capture is Dayan most closely associated? a. -

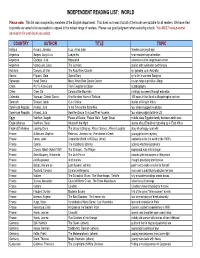

Independent Reading List: World

INDEPENDENT READING LIST: WORLD Please note: This list was compiled by members of the English department. That does not mean that all of the books are suitable for all readers. We have tried to provide as varied a list as possible to appeal to the widest range of readers. Please use good judgment when selecting a book. You MUST have parental permission for each book you select. COUNTRY AUTHOR TITLE TOPIC Antigua Kincaid, Jamaica Lucy, Annie John females coming of age Argentina Borges, Jorge Luis Labyrinths short stories/magical realism Argentina Cortazar, Julio Hopscotch adventures of an Argentinean writer Argentina Valenzuela, Luisa The Censors stories with symbolism and fantasy Australia Conway, Jill Ker The Road from Coorain girl growing up in Australia Bosnia Filipovic, Zlata Zlata's Diary girl's life in war-torn Sarajevo Botswana Head, Bessie Maru; When Rain Clouds Gather ex-con helps a primitive village China P'u Yi, Aisin-Gioro From Emperor to Citizen autobiography China Chen, Da Colors of the Mountain rural boy succeeds through education Colombia Marquez, Gabriel Garcia One Hundred Years of Solitude 100 years in the life of a village/magical realism Denmark Dinesen, Isaak Out of Africa stories of living in Africa Dominican Republic Alvarez, Julia In the Time of the Butterflies four sisters support revolution Dominican Republic Alvarez, Julia How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents four sisters adjust to life in US Egypt Mahfouz, Naguib Palace of Desire; Palace Walk; Sugar Street middle class Egyptian family between world wars -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript Pas been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissenation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from anytype of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material bad to beremoved, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with smalloverlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back ofthe book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell &Howell Information Company 300North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106-1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521·0600 THE LIN BIAO INCIDENT: A STUDY OF EXTRA-INSTITUTIONAL FACTORS IN THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY AUGUST 1995 By Qiu Jin Dissertation Committee: Stephen Uhalley, Jr., Chairperson Harry Lamley Sharon Minichiello John Stephan Roger Ames UMI Number: 9604163 OMI Microform 9604163 Copyright 1995, by OMI Company. -

Clare Hollingworth, First of the Female War Correspondents by Patrick Garrett

Of Fortunes and War: Clare Hollingworth, first of the female war correspondents by Patrick Garrett Ebook Of Fortunes and War: Clare Hollingworth, first of the female war correspondents currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Of Fortunes and War: Clare Hollingworth, first of the female war correspondents please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Paperback:::: 510 pages+++Publisher:::: Thistle Publishing (May 10, 2016)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 1910670847+++ISBN-13:::: 978-1910670842+++Product Dimensions::::5.5 x 1.3 x 8.5 inches++++++ ISBN10 1910670847 ISBN13 978-1910670 Download here >> Description: “A fascinating account of an extraordinary career. This vivid story, beautifully told, is unputdownable.”Alexander McCall Smith“Clare Hollingworth is certainly one of the most unforgettable journalists I have ever met and one of the greatest journalists of the 20th century.”Chris Patten“She was regarded by everyone as the most formidable foreign correspondent around, not just of women but out of everyone.”John Humphrys“Clare Hollingworth was one of the greatest reporters of the 20th century, and famously scooped the competition by reporting the German invasion of Poland in 1939 before anyone else did, for the Daily Telegraph.”Charles Moore“She was a pioneer.”Kate Adie OBE“Clare made an extraordinary impact in journalism. Who did the first interview with the Shah of Iran? Clare Hollingworth. Who did the last interview all those years – 30 – 40 - years later, after he fell? Clare Hollingworth. And she was the only person he wanted to speak to. And that’s really the measure of the woman.”John Simpson CBE“It was her dispatches that alerted the British Foreign Office to the fact that Germany had invaded Poland in 1939. -

University Micrcxilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality o f the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Israel ISRAEL

Israel I.H.T. Industries: food processing, diamond cutting and polishing, textiles and ISRAEL apparel, chemicals, metal products, military equipment, transport equipment, electrical equipment, potash mining, high-technology electronics, tourism Currency: 1 new Israeli shekel (NIS) = 100 new agorot Railways: total: 610 km standard gauge: 610 km 1.435-m gauge (1996) Highways: total: 15,965 km paved: 15,965 km (including 56 km of expressways) unpaved: 0 km (1998 est.) Ports and Harbors: Ashdod, Ashqelon, Elat (Eilat), Hadera, Haifa, Tel Aviv- Yafo Airports: 58 (1999 est.) Airports - with paved runways: total: 33 over 3,047 m: 2 2,438 to 3,047 m: 7 1,524 to 2,437 m: 7 914 to 1,523 m: 10 under 914 m: 7 (1999 est.) Airports - with unpaved runways: total: 25 2,438 to 3,047 m: 1 1,524 to 2,437 m: 2 914 to 1,523 m: 2 under 914 m: 20 (1999 est.) Heliports: 2 (1999 est.) Visa: required by all on arrival, subject to frequent changes. goods permitted: 250 cigarettes or 250g of tobacco products, 1 litre Duty Free: of spirits and 2 litres of wine, 250ml of eau de cologne or perfume, gifts up to the value of US$125. Health: no specific health precautions. HOTELS●MOTELS●INNS BEERSHEBA Country Dialling Code (Tel/Fax): ++972 THE BEERSHEBA DESERT INN LTD Ministry of Tourism: PO Box 1018 King George Street 24 Jerusalem Tel: (2) 675 Tuviyahu Av 4811 Fax: (2) 625 7955 Website: www.infotour.co.ul P.O.Box 247 TEL: +972 7 642 4922-9 Capital: Jerusalem Time: GMT + 2 Beersheba 84 102 FAX:+972 7 6412 772 Background: Following World War II, the British withdrew from their mandate of ISRAEL www.desertinn-hotel.com Palestine, and the UN partitioned the area into Arab and Jewish states, an E-mail: [email protected] arrangement rejected by the Arabs.