University Micrcxilms International 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Shriek of Silence: a Phenomenology of the Holocaust Novel

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in General English Language and Literature 2014 The Shriek of Silence: A Phenomenology of the Holocaust Novel David Patterson Oklahoma State University Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Patterson, David, "The Shriek of Silence: A Phenomenology of the Holocaust Novel" (2014). Literature in General. 3. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_literature_in_general/3 THE SHRIEK OF SILENCE This page intentionally left blank THE OFSILENCE APhenomenology of the Holocaust Novel DAVID PATTERSON THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Copyright © 1992 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Patterson, David, 1948- The shriek of silence : a phenomenology of the Holocaust novel / David Patterson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8131-6013-9 1. Holocaust, Jewish (1939-1945), in literature. 2. Jewish fiction-History and criticism. I. Title. PN56.H55P38 1992 809' .93358-dc20 91-17269 This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. -

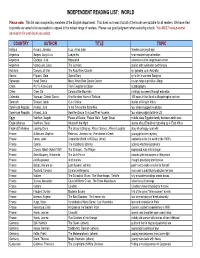

Independent Reading List: World

INDEPENDENT READING LIST: WORLD Please note: This list was compiled by members of the English department. That does not mean that all of the books are suitable for all readers. We have tried to provide as varied a list as possible to appeal to the widest range of readers. Please use good judgment when selecting a book. You MUST have parental permission for each book you select. COUNTRY AUTHOR TITLE TOPIC Antigua Kincaid, Jamaica Lucy, Annie John females coming of age Argentina Borges, Jorge Luis Labyrinths short stories/magical realism Argentina Cortazar, Julio Hopscotch adventures of an Argentinean writer Argentina Valenzuela, Luisa The Censors stories with symbolism and fantasy Australia Conway, Jill Ker The Road from Coorain girl growing up in Australia Bosnia Filipovic, Zlata Zlata's Diary girl's life in war-torn Sarajevo Botswana Head, Bessie Maru; When Rain Clouds Gather ex-con helps a primitive village China P'u Yi, Aisin-Gioro From Emperor to Citizen autobiography China Chen, Da Colors of the Mountain rural boy succeeds through education Colombia Marquez, Gabriel Garcia One Hundred Years of Solitude 100 years in the life of a village/magical realism Denmark Dinesen, Isaak Out of Africa stories of living in Africa Dominican Republic Alvarez, Julia In the Time of the Butterflies four sisters support revolution Dominican Republic Alvarez, Julia How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents four sisters adjust to life in US Egypt Mahfouz, Naguib Palace of Desire; Palace Walk; Sugar Street middle class Egyptian family between world wars -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

Lessing the Fifth Child.Pdf

Doris Lessing was born of British parents in Persia (now Iran) in 1919 and was taken to Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) when she was five. She spent her childhood on a large farm there and first came to England in 1949. She brought with her the manuscript of her first novel, The Grass is Singing, which was published in 1950 with outstanding success in Britain, in America, and in ten European countries. Since then her international repu- tation not only as a novelist but as a non-fiction and short story writer has flourished. For her collection of short novels, Five, she was honoured with the 1954 Somerset Maugham Award. She was awarded the Austrian State Prize for European Literature in 1981, and the German Federal Republic Shakespeare Prize of 1982. Among her other celebrated novels are The Golden Notebook, The Summer Before the Dark, Memoirs of a Survivor and the five volume Children of Violence series. Her short stories have been collected in a number of volumes, including To Room Nineteen and The Temptation of Jack Orkney; while her African stories appear in This Was the Old Chief's Country and The Sun Between Their Feet. Shikasta, the first in a series of five novels with the overall title of Canopus in Argos: Archives, was published in 1979. Her novel The Good Terrorist won the W. H. Smith Literary Award for 1985, and the Mondello Prize in Italy that year. The Fifth Child won the Grinzane Cavour Prize in Italy, an award voted on by students in their final year at school. -

Spelman's Political Warriors

SPELMAN Spelman’s Stacey Abrams, C’95 Political Warriors INSIDE Stacey Abrams, C’95, a power Mission in Service politico and quintessential Spelman sister Kiron Skinner, C’81, a one-woman Influencers in strategic-thinking tour de force Advocacy, Celina Stewart, C’2001, a sassy Government and woman getting things done Public Policy THE ALUMNAE MAGAZINE OF SPELMAN COLLEGE | SPRING 2019 | VOL. 130 NO. 1 SPELMAN EDITOR All submissions should be sent to: Renita Mathis Spelman Messenger Office of Alumnae Affairs COPY EDITOR 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., Box 304 Beverly Melinda James Atlanta, GA 30314 OR http://www.spelmanlane.org/SpelmanMessengerSubmissions GRAPHIC DESIGNER Garon Hart Submission Deadlines: Fall Issue: Submissions Jan. 1 – May 31 ALUMNAE DATA MANAGER Spring Issue: Submissions June 1 – Dec. 31 Danielle K. Moore ALUMNAE NOTES EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE Alumnae Notes is dedicated to the following: Jessie Brooks • Education Joyce Davis • Personal (birth of a child or marriage) Sharon E. Owens, C’76 • Professional Jane Smith, C’68 Please include the date of the event in your submission. TAKE NOTE! EDITORIAL INTERNS Take Note! is dedicated to the following alumnae Melody Greene, C’2020 achievements: Jana Hobson, C’2019 • Published Angelica Johnson, C’2019 • Appearing in films, television or on stage Tierra McClain, C’2021 • Special awards, recognition and appointments Asia Riley, C’2021 Please include the date of the event in your submission. WRITERS BOOK NOTES Maynard Eaton Book Notes is dedicated to alumnae and faculty authors. Connie Freightman Please submit review copies. Adrienne Harris Tom Kertscher IN MEMORIAM We honor our Spelman sisters. If you receive notice Alicia Lurry of the death of a Spelman sister, please contact the Kia Smith, C’2004 Office of Alumnae Affairs at 404-270-5048 or Cynthia Neal Spence, C’78, Ph.D. -

Twilight of the Anthropocene Idols

Twilight of theTwilight of Anthropocene Idols Following on from Theory and the Disappearing Future, Cohen, Colebrook and Miller turn their attention to the eco-critical and environmental humanities’ newest and most fashionable of concepts, the Anthropocene. The question that has escaped focus, as ‘tipping points’ are acknowledged as passed, is how language, mnemo-tech- Twilight of the Anthropocene Idols nologies and the epistemology of tropes appear to guide the accelerating ecocide, and how that implies a mutation within reading itself—from the era of extinction events. Tom Cohen, Claire Colebrook amd J. Hillis Miller There’s something uncanny about the very word Anthropocene. Perhaps it is in the way it seems to arrive too early and too late. It describes something that is still happening as if it had happened. Perhaps it is that it seems to implicate something about the ‘human’ but from a vantage point where the human would be over and done with, or never really existed in the first place. And so besides the crush of data there’s a problem of language to attend to in thinking where and when and who we are or could ever be or have been. Cohen, Colebrook and Miller do us the courtesy of taking the Anthropocene to be a name that marks both the state of the world and the state of language. They bring their consider- able collective resources to bear on this state of language, that we might better weave words that attend to the state of the world. McKenzie Wark, author of Molecular Red: Theory for the Anthropocene With breathtaking fearlessness, the authors expose the full extent of the Enlight- enment shell game: not only have ‘we’ never been modern, we’ve never even been human. -

Freshman Year Reading Catalog 2017–2018

Simon & Schuster Freshman Year Reading Catalog 2017–2018 FreshmanYearReads.com Dear FYE Committee Member, We are delighted to present the 2017 – 2018 Freshman Year Reading catalog from Simon & Schuster. Simon & Schuster publishes a wide variety of fiction and nonfiction titles that align with the core purpose of college and university programs across the country—to support students in transition, promote engaging conversations, explore diverse perspectives, and foster community during the college experience. If you don’t see a title that fits your program’s needs, we are ready to work with you to find the perfect book for your campus or community program. Visit FreshmanYearReads.com for author videos, reading group guides, and to request review copies. For questions about discounts on large orders, or if you’re interested in having an author speak on campus, please email [email protected]. We’d love to hear from you! For a full roster of authors available for speaking engagements, visit the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at SimonSpeakers.com. You can also contact the Speakers Bureau directly by calling (866) 248-3049 or by emailing [email protected]. If the author you are interested in is not represented by the Speakers Bureau, please send us an email at [email protected]. Best, The Simon & Schuster Education & Library Group ORDERING INFO Simon & Schuster offers generous discounts on bulk purchases of books for FYE programs, one-reads, and educational use where the books are given away. The breakdown -

The Case of Golden Dawn

THE TERRORIST ACTIVITY OF NEO-NAZI ORGANISATIONS IN EUROPE: THE CASE OF GOLDEN DAWN By Kevin Ovenden The Fuhrer of Golden Dawn, of N. Michaloliakos Fuhrer The 1. Introduction 2017 has seen a further worrying growth of far right and fascist forma- tions in several European countries. May brought the advance of Marine Le Pen into the second round of the French presidential election. The following month the Front Na- tional increased its presence in the French National Assembly, though fell short of the numbers to form an official parliamentary group. In September the Alternative for Germany (AfD) made a major breakthrough to enter the Bundestag for the first time, winning 12.6 percent of the national vote. The party has gone through a succes- sion of radicalisations since its formation as a free-market Euroscep- tic party. It now has a hardened anti-Muslim central ideology, which organises its propaganda and programme. Most concerning is that its growth as an electoral force has been accompanied by the increas- ing weight of its «fascisising wing». Entry into first regional-state and now the federal parliaments has not provided a «domestication» of its message. Far from it. At one end of the spectrum of radical right wing formations in Eu- rope – ranging from racist populists to fascists – stands Golden Dawn in Greece. It is a neo-nazi party. Its leader, Nikos Michaloliakos, says that Golden Dawn hails from «the seeds of the defeated army of 1945», that is from the beaten armed forces of the Third Reich. It was the third party in the Greek parliament elected in Septem- ber 2015. -

The Transformations of Babi Yar

FINAL REPORT TO NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H TITLE : The Transformations of Babi Yar AUTHOR : Richard Sheldo n CONTRACTOR : Research Institute of International Change , Columbia Universit y PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR : Seweryn Biale r COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 801-1 5 r DATE : The work leading to this report was supported by funds provide d by the National Council for Soviet and East European Research . THE NATIONAL COUNCI L FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H Leon S . Lipson Suite 304 Chairman, Board of Trustees 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, N .W . Vladimir I . T ouman off Washingtn, D.C. 200 36 Executive (202) 387-0168 PREFAC E This report is one of 13 separate papers by differen t authors which, assembled, will constitute the chapters of a Festschrift volume in honor of Professor Vera S . Dunham, to b e published by Westview Press . The papers will be distribute d individually to government readers by the Council in advance o f editing and publication by the Press, and therefore, may not b e identical to the versions ultimately published . The Contents for the entire series appears immediatel y following this Preface . As distributed by the Council, each individual report wil l contain this Preface, the Contents, the Editor's Introductio n for the pertinent division (I, II, or III) of the volume, an d the separate paper itself . BOARD OF TRUSTEES : George Breslauer; Herbert J . Ellison; Sheila Fitzpatrick ; Ed . A . Hewett (Vice Chairman) ; David Joravsky ; Edward L. Keenan ; Robert Legvold ; Herbert S . Levine; Leon S . Lipson (Chairman) ; Paul Marer; Daniel C. -

The Heralds of the Dawn: a History of the Motion Picture Industry in the State of Florida, 1908-2019

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2019 The Heralds of the Dawn: A History of the Motion Picture Industry in the State of Florida, 1908-2019 David Morton University of Central Florida Part of the Film Production Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Morton, David, "The Heralds of the Dawn: A History of the Motion Picture Industry in the State of Florida, 1908-2019" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 6365. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/6365 “THE HERALDS OF THE DAWN:” A HISTORY OF THE MOTION PICTURE INDUSTRY IN THE STATE OF FLORIDA, 1908-2019 by DAVID D. MORTON B.A. East Stroudsburg University, 2009 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2014 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Texts and Technology in the Department of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2019 Major Professor: Scot French © 2019 David Morton ii ABSTRACT Often overlooked in its contribution to cinema history, the State of Florida has the distinction of being among just a handful of regions in the United States to have a continuous connection with the American motion picture industry. -

Jewishreviewofbooks

The Mabam Strategy by Amos Yadlin & Ari Heistein JEWISH REVIEW Volume 10, Number 1 Spring 2019 $10.45 OF BOOKS John J. Clayton Nobody Expects the Inquisition: A Memoir Michael Weingrad Harold Bloom’s Science Fiction Diane Cole Giorgio Bassani’s Memory Garden Plus: Nathan Englander’s New Novel, Aleph-Bet Mysticism, Mizrahi Spies, and more Editor BRANDEIS Abraham Socher Senior Contributing Editor Allan Arkush UNIVERSITY PRESS Art Director Spinoza’s Challenge to Jewish Thought Betsy Klarfeld Writings on His Life, Philosophy, and Legacy Managing Editor Edited by Daniel B. Schwartz Amy Newman Smith “This collection of Jewish views on, and responses to, Spinoza over Editorial Assistant the centuries is an extremely useful addition to the literature. That Kate Elinsky it has been edited by an expert on Spinoza’s legacy in the Jewish world only adds to its value.” Steven Nadler, University of Wisconsin Editorial Board Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri March 2019 Leora Batnitzky Ruth Gavison Moshe Halbertal Hillel Halkin Jon D. Levenson Anita Shapira Michael Walzer J. H.H. Weiler Ruth R. Wisse Steven J. Zipperstein Executive Director Eric Cohen Associate Publisher Nadia Ai Kahn Chairman’s Council Blavatnik Family Foundation Publication Committee Marilyn and Michael Fedak The Donigers of Not Bad for The Soul of the Stranger Ahuva and Martin J. Gross Great Neck Delancey Street Reading God and Torah from Susan and Roger Hertog A Mythologized Memoir The Rise of Billy Rose a Transgender Perspective The Lauder Foundation– Wendy Doniger Mark Cohen Joy Ladin Leonard and Judy Lauder “This heartfelt, difficult work will “Walking through the snow to see “Comprehensive biography . -

The Child of Dawn

THE CHILD OF DAWN & BOOK OF RAPHA: A PROPHETIC & POETICAL MISCELLANY: WHEREIN IS EXPOUNDED THE MYSTERY OF BEING; THE ORIGIN & END OF CREATION; NATURE & SUPERNATURE; ALSO THE WAY OF DELIVERANCE FOR THE SOUL FROM MATTER TO SPIRIT; AS IT GREW & TOOK FORM DURING THE MAKING OF THIS BOOK; FINALLY & ESPECIALLY, A REVELATION OF THE DAWN OF A NEW DISPENSATION, & ELUCIDATION OF WHAT IS MYSTICALLY MEANT BY THE DIVINE CHILDHOOD [Here a little picture—J.C. as a boy, with halo, reading a book, and holding a cross.] The holy Child Iesous on Mount Calvary introduced his Divine Humanity into the very ultimates of nature, thereby making spiritual salvation available for all & each. He will never come again in the flesh. But He is at this very day returning to our earth in an interior mystical way, in order to complete the work he then began. His name in the heaven of heavens is Ra-El-Phaos. (Made in obedience to the dictate within by Ralph) THE SOUL & THE SAVIOUR “Little bird That beat’st in vain Thy wings against The windowpane, “Be guided by My loving hands. The door is near And open stands!” “Alas, for dread I cannot fly. Oh, touch me not Or I shall die!” JESUS CHRIST is the universal Saviour and Shepherd, who alone can guide all the lost sheep & lambs into one fold. (By these are meant the stray emotions and wandering proclivities of the soul so dear to Freud and his followers). Rapha is an aspect of his sovereignty. Science is the blind leading the blind.