Land Monopoly and Twentieth Century American Utility Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amos Pinchot and Atomistic Capitalism: a Study in Reform Ideas

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1973 Amos Pinchot and Atomistic Capitalism: a Study in Reform Ideas. Rex Oliver Mooney Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Mooney, Rex Oliver, "Amos Pinchot and Atomistic Capitalism: a Study in Reform Ideas." (1973). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2484. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2484 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Download Catalog

Abraham Lincoln Book Shop, Inc. Catalog 183 Holiday/Winter 2020 HANDSOME BOOKS IN LEATHER GOOD HISTORY -- IDEAL AS HOLIDAY GIFTS FOR YOURSELF OR OTHERS A. Badeau, Adam. MILITARY HISTORY OF ULYSSES S. GRANT, FROM APRIL 1861 TO APRIL 1865. New York: 1881. 2nd ed.; 3 vol., illus., all maps. Later full leather; gilt titled and decorated spines; marbled endsheets. The military secretary of the Union commander tells the story of his chief; a detailed, sympathetic account. Excellent; handsome. $875.00 B. Beveridge, Albert J. ABRAHAM LINCOLN 1809-1858. Boston: 1928. 4 vols. 1st trade edition in the Publisher’s Presentation Binding of ½-tan leather w/ sp. labels; deckled edges. This work is the classic history of Lincoln’s Illinois years -- and still, perhaps, the finest. Excellent; lt. rub. only. Set of Illinois Governor Otto Kerner with his library “name” stamp in each volume. $750.00 C. Draper, William L., editor. GREAT AMERICAN LAWYERS: THE LIVES AND INFLUENCE OF JUDGES AND LAWYERS WHO HAVE ACQUIRED PERMANENT NATIONAL REPUTATION AND HAVE DEVELOPED THE JURISPRUDENCE OF THE UNITED STATES. Phila.: John Winston Co.,1907. #497/500 sets. 8 volumes; ¾-morocco; marbled boards/endsheets; raised bands; leather spine labels; gilt top edges; frontis.; illus. Marshall, Jay, Hamilton, Taney, Kent, Lincoln, Evarts, Patrick Henry, and a host of others have individual chapters written about them by prominent legal minds of the day. A handsome set that any lawyer would enjoy having on his/her shelf. Excellent. $325.00 D. Freeman, Douglas Southall. R. E. LEE: A BIOGRAPHY. New York, 1936. “Pulitzer Prize Edition” 4 vols., fts., illus., maps. -

Nfbidlovesbiz #STOPBYSHOPBUY

NORTH FLATBUSH BID CONNECTING COMMUNITIES FOR OVER 30 YEARS Visit us at: NORTHFLATBUSHBID.NYC 282 Flatbush Avenue Brooklyn New York 11217 718-783-1685 · [email protected] Design by AGD Studio · www.agd.studio Stay connected with us: #NFBIDlovesBIZ #STOPBYSHOPBUY @NORTHFLATBUSHBK @NFBID NFBID: OUR BACKGROUND NFBID: DISTRICT MAP & BOARD MEMBERS N Take a further look: Scale of map: NFBID.COM/SHOP 1 in = 250 ft NORTH FLATBUSH BID Greetings! B45 B67 CLASS A: PROPERTY OWNERS A little over 35 years ago, a group of committed citizens joined BAM BAM ATLANTIC AVE & forces to improve the area known as North Flatbush Avenue. These 3RD AVENUE SHARP HARVEY BARCLAYS CENTER committed citizens, along with the assistance of elected officials B D N R Q WILLIAMSBURGH FULTON STREET President, Ms. Regina Cahill and city agencies, brought renewal to Flatbush Avenue beginning SAVINGS BANK with the “Triangle Parks Commission” and the North Flatbush Avenue TOWER Vice President, Mr. Michael Pintchik Betterment Committee that ultimately gave rise to the North Flatbush B37 Secretary & Treasurer, Ms. Diane Allison Business Improvement District (NFBID). This corridor along Flatbush B65 B45 ATLANTIC AVE & BARCLAYS CENTER Avenue from Atlantic Avenue towards Prospect Park connects NORTH B103 FLATBUSH 2 3 4 5 Mr. Abed Awad residential communities like Park Slope, Prospect Heights, Pacific Park BID B63 and bustling Downtown to the peaceful Prospect Park and beyond Mr. Scott Domansky 4TH AVENUE B41 with a slew of transportation links and the Avenue traveling from the B65 BARCLAYS Mr. Chris King Manhattan Bridge to the bay. B67 CENTER Mr. Matthew Pintchik Over the years, the members of the NFBID Board of Directors, BERGEN ST ATLANTIC AVENUE Mr. -

The Bishop, the Coach & the Mayor

Saint Mary's College of California Saint Mary's Digital Commons Scholarship, Research, Creative Activities, and Interdisciplinary Works Community Engagement Spring 2014 The Bishop, The Coach & The Mayor: Three Characters in College History L. Raphael Patton FSC Saint Mary's College of California, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.stmarys-ca.edu/collaborative-works Repository Citation Patton, L. Raphael FSC. The Bishop, The Coach & The Mayor: Three Characters in College History (2014). [article]. https://digitalcommons.stmarys-ca.edu/collaborative-works/49 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship, Research, Creative Activities, and Community Engagement at Saint Mary's Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Interdisciplinary Works by an authorized administrator of Saint Mary's Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The Bishop, The Coach & The Mayor Three characters in College history Saint Mary’s College 2 3 The Bishop: Alemany and his college Preface 5 Introduction 7 1 California 9 2 Spain 17 3 Church 21 4 San Francisco 27 5 The Vicar General 33 6 Italy 41 7 Later Years 45 8 The end 49 Appendices 55 Saint Mary’s College 4 5 Preface The history of the Church in California, the history of Saint Mary’s College and the story of the Dominicans on the West Coast have each been written and rewritten, supported by impressive scholarship. Archives, newspaper morgues and libraries have been mined for material. -

The Inventory of the Theodore Roosevelt Collection #560

The Inventory of the Theodore Roosevelt Collection #560 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOSEVELT, THEODORE 1858-1919 Gift of Paul C. Richards, 1976-1990; 1993 Note: Items found in Richards-Roosevelt Room Case are identified as such with the notation ‘[Richards-Roosevelt Room]’. Boxes 1-12 I. Correspondence Correspondence is listed alphabetically but filed chronologically in Boxes 1-11 as noted below. Material filed in Box 12 is noted as such with the notation “(Box 12)”. Box 1 Undated materials and 1881-1893 Box 2 1894-1897 Box 3 1898-1900 Box 4 1901-1903 Box 5 1904-1905 Box 6 1906-1907 Box 7 1908-1909 Box 8 1910 Box 9 1911-1912 Box 10 1913-1915 Box 11 1916-1918 Box 12 TR’s Family’s Personal and Business Correspondence, and letters about TR post- January 6th, 1919 (TR’s death). A. From TR Abbott, Ernest H[amlin] TLS, Feb. 3, 1915 (New York), 1 p. Abbott, Lawrence F[raser] TLS, July 14, 1908 (Oyster Bay), 2 p. ALS, Dec. 2, 1909 (on safari), 4 p. TLS, May 4, 1916 (Oyster Bay), 1 p. TLS, March 15, 1917 (Oyster Bay), 1 p. Abbott, Rev. Dr. Lyman TLS, June 19, 1903 (Washington, D.C.), 1 p. TLS, Nov. 21, 1904 (Washington, D.C.), 1 p. TLS, Feb. 15, 1909 (Washington, D.C.), 2 p. Aberdeen, Lady ALS, Jan. 14, 1918 (Oyster Bay), 2 p. Ackerman, Ernest R. TLS, Nov. 1, 1907 (Washington, D.C.), 1 p. Addison, James T[hayer] TLS, Dec. 7, 1915 (Oyster Bay), 1p. Adee, Alvey A[ugustus] TLS, Oct. -

The "Private History," Grant, and West Point: Mark Twain's Exculpatory Triad

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1981 The "Private History," Grant, and West Point: Mark Twain's exculpatory triad Franklin J. Hillson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hillson, Franklin J., "The "Private History," Grant, and West Point: Mark Twain's exculpatory triad" (1981). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625139. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-kx9e-8147 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The "Private History," Grant, and West Point H Mark Twain’s Exculpatory Triad A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Franklin J. Hillson APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts ^Author Approved, June 1981 c— Carl Dolmetsch William F. Davis Scott Donaldson ABSTRACT This essay explores three interrelated episodes in the career of Samuel L. Clemens, "Mark Twain": the writing of his "Private History of a Campaign That Failed," his relationship with General Ulysses S. Grant, and his asso ciation with the United States Military Academy. Each element of this triad was responsible for aiding in the self-exculpation of the guilt that Twain suffered in the Civil War. -

Congestion Pricing: a Step Toward Safer Streets?

Congestion Pricing: A Step Toward Safer Streets? Examining the Relationship Between Urban Core Congestion Pricing and Safety on City Streets A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Architecture and Planning COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Urban Planning by Andrew Lassiter Advisor: Dr. David King | Reader: Dr. Floyd Lapp May 2016 Lassiter / Congestion Pricing: A Step Toward Safer Streets? (2016) 2 Key Words Congestion pricing, traffic safety, Vision Zero, transportation economics, street safety, planning discourse, London, Stockholm, New York City Research Question Is urban core congestion pricing understood to improve street safety? ● Is there evidence to indicate that congestion pricing implementation can improve safety? ● Is street safety a significant element of the congestion pricing discourse? ● If so, can we determine a consensus from that discourse as to whether congestion pricing reduces crashes and casualties on city streets? ● Are there opportunities to create an integrated framework that draws from both congestion pricing and street safety conversations? Abstract This thesis explores cordon-style urban core congestion pricing as a street safety mechanism. With a handful of cities around the world having implemented different versions of cordon-style pricing, and conversations about street safety growing through the increasing adoption of Vision Zero in the United States and Europe, is there a nexus between these two policies? This research examines case studies of congestion pricing in London, Stockholm and New York; and assesses the relationship, both real and perceived, that is present in each city and in the literature between pricing and safety. -

The Roles of George Perkins and Frank Munsey in the Progressive

“A Progressive Conservative”: The Roles of George Perkins and Frank Munsey in the Progressive Party Campaign of 1912 A thesis submitted by Marena Cole in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Tufts University May 2017 Adviser: Reed Ueda Abstract The election of 1912 was a contest between four parties. Among them was the Progressive Party, a movement begun by former president Theodore Roosevelt. George Perkins and Frank Munsey, two wealthy businessmen with interests in business policy and reform, provided the bulk of the Progressive Party’s funding and proved crucial to its operations. This stirred up considerable controversy, particularly amongst the party’s radical wing. One Progressive, Amos Pinchot, would later say that the two corrupted and destroyed the movement. While Pinchot’s charge is too severe, particularly given the support Perkins and Munsey had from Roosevelt, the two did push the Progressive Party to adopt a softer program on antitrust regulation and enforcement of the Sherman Antitrust Act. The Progressive Party’s official position on antitrust and the Sherman Act, as shaped by Munsey and Perkins, would cause internal ideological schisms within the party that would ultimately contribute to the party’s dissolution. ii Acknowledgements This thesis finalizes my time at the Tufts University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, which has been a tremendously challenging and fulfilling place to study. I would first like to thank those faculty at Boston College who helped me find my way to Tufts. I have tremendous gratitude to Lori Harrison-Kahan, who patiently guided me through my first experiences with archival research. -

NYCTRC Minutes 2.22.18 W Presentation

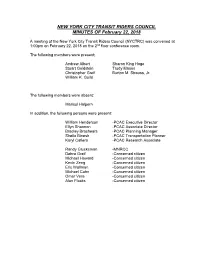

NEW YORK CITY TRANSIT RIDERS COUNCIL MINUTES OF February 22, 2018 A meeting of the New York City Transit Riders Council (NYCTRC) was convened at 1:00pm on February 22, 2018 on the 2nd floor conference room. The following members were present: Andrew Albert Sharon King Hoge Stuart Goldstein Trudy Mason Christopher Greif Burton M. Strauss, Jr. William K. Guild The following members were absent: Marisol Halpern In addition, the following persons were present: William Henderson -PCAC Executive Director Ellyn Shannon -PCAC Associate Director Bradley Brashears -PCAC Planning Manager Sheila Binesh -PCAC Transportation Planner Karyl Cafiero -PCAC Research Associate Randy Glucksman -MNRCC Debra Greif -Concerned citizen Michael Howard -Concerned citizen Kevin Zeng -Concerned citizen Eric Wollman -Concerned citizen Michael Cohn -Concerned citizen Omar Vera -Concerned citizen Alan Flacks -Concerned citizen NYCTRC MINUTES -2 - Time Point Video Part 1 00:04 Approval of Agenda The agenda for the February 22, 2018 Meeting were approved. Approval of Minutes The minutes of the January 25, 2018 meeting were approved as 00:56 amended with corrections 01:51 Chair’s Report (The Chair’s Report is attached to minutes.) 03:24 A. Albert: Paying bus ridership is down, slow buses, Andy Byford’s customer focus, L train closure 06:30 T. Mason: Unclear/improper announcements communications 09:08 New MTA graphics discussion. 10:26 Introduction of Presenter: Sam Schwartz of MoveNY and FixNYC presents on Congestion Pricing proposal. 20:10 A. Albert: Bloomberg Plan only charged people entering across the East River or across northern cordon, while FixNYC allows for some free entry to FDR Drive. -

Hypergeorgism: When Rent Taxation Is Socially Optimal∗

Hypergeorgism: When rent taxation is socially optimal∗ Ottmar Edenhoferyz, Linus Mattauch,x Jan Siegmeier{ June 25, 2014 Abstract Imperfect altruism between generations may lead to insufficient capital accumulation. We study the welfare consequences of taxing the rent on a fixed production factor, such as land, in combination with age-dependent redistributions as a remedy. Taxing rent enhances welfare by increasing capital investment. This holds for any tax rate and recycling of the tax revenues except for combinations of high taxes and strongly redistributive recycling. We prove that specific forms of recycling the land rent tax - a transfer directed at fundless newborns or a capital subsidy - allow reproducing the social optimum under pa- rameter restrictions valid for most economies. JEL classification: E22, E62, H21, H22, H23, Q24 Keywords: land rent tax, overlapping generations, revenue recycling, social optimum ∗This is a pre-print version. The final article was published at FinanzArchiv / Public Finance Analysis, doi: 10.1628/001522115X14425626525128 yAuthors listed in alphabetical order as all contributed equally to the paper. zMercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change, Techni- cal University of Berlin and Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. E-Mail: [email protected] xMercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change. E-Mail: [email protected] {(Corresponding author) Technical University of Berlin and Mercator Research Insti- tute on Global Commons and Climate Change. Torgauer Str. 12-15, D-10829 Berlin, E-Mail: [email protected], Phone: +49-(0)30-3385537-220 1 1 INTRODUCTION 2 1 Introduction Rent taxation may become a more important source of revenue in the future due to potentially low growth rates and increased inequality in wealth in many developed economies (Piketty and Zucman, 2014; Demailly et al., 2013), concerns about international tax competition (Wilson, 1986; Zodrow and Mieszkowski, 1986; Zodrow, 2010), and growing demand for natural resources (IEA, 2013). -

Amos Pinchot: Rebel Prince Nancy Pittman Pinchot Guilford, Connecticut

Amos Pinchot: Rebel Prince Nancy Pittman Pinchot Guilford, Connecticut A rebel is the kind of person who feels his rebellion not as a plea for this or that reform, but as an unbearable tension in his viscera. [He has] to break down the cause of his frustration or jump out of his skin. -Walter Lippmann' Introduction Amos Richards Eno Pinchot, if remembered at all, is usually thought of only as the younger, some might say lesser, brother of Gifford Pinchot, who founded the Forest Service and then became two-time governor of Pennsylva- nia. Yet Amos Pinchot, who never held an important position either in or out of government and was almost always on the losing side, was at the center of most of the great progressive fights of the first half of this century. His life and Amos and GirdPinchot Amos Pinchot: Rebel Prince career encompassed two distinct progressive eras, anchored by the two Roosevelt presidencies, during which these ideals achieved their greatest gains. During the twenty years in between, many more battles were lost than won, creating a discouraging climate. Nevertheless, as a progressive thinker, Amos Pinchot held onto his ideals tenaciously. Along with many others, he helped to form an ideological bridge which safeguarded many of the ideas that might have perished altogether in the hostile climate of the '20s. Pinchot seemed to thrive on adversity. Already out of step by 1914, he considered himself a liberal of the Jeffersonian stamp, dedicated to the fight against monopoly. In this, he was opposed to Teddy Roosevelt, who, was cap- tivated by Herbert Croly's "New Nationalism," extolled big business controlled by even bigger government. -

Working Paper No. 40, the Rise and Fall of Georgist Economic Thinking

Portland State University PDXScholar Working Papers in Economics Economics 12-15-2019 Working Paper No. 40, The Rise and Fall of Georgist Economic Thinking Justin Pilarski Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/econ_workingpapers Part of the Economic History Commons, and the Economic Theory Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Pilarski, Justin "The Rise and Fall of Georgist Economic Thinking, Working Paper No. 40", Portland State University Economics Working Papers. 40. (15 December 2019) i + 16 pages. This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Working Papers in Economics by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Rise and Fall of Georgist Economic Thinking Working Paper No. 40 Authored by: Justin Pilarski A Contribution to the Working Papers of the Department of Economics, Portland State University Submitted for: EC456 “American Economic History” 15 December 2019; i + 16 pages Prepared for Professor John Hall Abstract: This inquiry seeks to establish that Henry George’s writings advanced a distinct theory of political economy that benefited from a meteoric rise in popularity followed by a fall to irrelevance with the turn of the 20th century. During the depression decade of the 1870s, the efficacy of the laissez-faire economic system came into question, during this same timeframe neoclassical economics supplanted classical political economy. This inquiry considers both of George’s key works: Progress and Poverty [1879] and The Science of Political Economy [1898], establishing the distinct components of Georgist economic thought.