Congestion Pricing: a Step Toward Safer Streets?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In New York City

Outdoors Outdoors THE FREE NEWSPAPER OF OUTDOOR ADVENTURE JULY / AUGUST / SEPTEMBER 2009 iinn NNewew YYorkork CCityity Includes CALENDAR OF URBAN PARK RANGER FREE PROGRAMS © 2009 Chinyera Johnson | Illustration 2 CITY OF NEW YORK PARKS & RECREATION www.nyc.gov/parks/rangers URBAN PARK RANGERS Message from: Don Riepe, Jamaica Bay Guardian To counteract this problem, the American Littoral Society in partnership with NYC Department of Parks & Recreation, National Park Service, NYC Department of Environmental Protection, NY State Department of Environmental Conservation, Jamaica Bay EcoWatchers, NYC Audubon Society, NYC Sierra Club and many other groups are working on various projects designed to remove debris and help restore the bay. This spring, we’ve organized a restoration cleanup and marsh planting at Plum Beach, a section of Gateway National Recreation Area and a major spawning beach for the ancient horseshoe crab. In May and June during the high tides, the crabs come ashore to lay their eggs as they’ve done for millions of years. This provides a critical food source for the many species of shorebirds that are migrating through New York City. Small fi sh such as mummichogs and killifi sh join in the feast as well. JAMAICA BAY RESTORATION PROJECTS: Since 1986, the Littoral Society has been organizing annual PROTECTING OUR MARINE LIFE shoreline cleanups to document debris and create a greater public awareness of the issue. This September, we’ll conduct Home to many species of fi sh & wildlife, Jamaica Bay has been many cleanups around the bay as part of the annual International degraded over the past 100 years through dredging and fi lling, Coastal Cleanup. -

Nfbidlovesbiz #STOPBYSHOPBUY

NORTH FLATBUSH BID CONNECTING COMMUNITIES FOR OVER 30 YEARS Visit us at: NORTHFLATBUSHBID.NYC 282 Flatbush Avenue Brooklyn New York 11217 718-783-1685 · [email protected] Design by AGD Studio · www.agd.studio Stay connected with us: #NFBIDlovesBIZ #STOPBYSHOPBUY @NORTHFLATBUSHBK @NFBID NFBID: OUR BACKGROUND NFBID: DISTRICT MAP & BOARD MEMBERS N Take a further look: Scale of map: NFBID.COM/SHOP 1 in = 250 ft NORTH FLATBUSH BID Greetings! B45 B67 CLASS A: PROPERTY OWNERS A little over 35 years ago, a group of committed citizens joined BAM BAM ATLANTIC AVE & forces to improve the area known as North Flatbush Avenue. These 3RD AVENUE SHARP HARVEY BARCLAYS CENTER committed citizens, along with the assistance of elected officials B D N R Q WILLIAMSBURGH FULTON STREET President, Ms. Regina Cahill and city agencies, brought renewal to Flatbush Avenue beginning SAVINGS BANK with the “Triangle Parks Commission” and the North Flatbush Avenue TOWER Vice President, Mr. Michael Pintchik Betterment Committee that ultimately gave rise to the North Flatbush B37 Secretary & Treasurer, Ms. Diane Allison Business Improvement District (NFBID). This corridor along Flatbush B65 B45 ATLANTIC AVE & BARCLAYS CENTER Avenue from Atlantic Avenue towards Prospect Park connects NORTH B103 FLATBUSH 2 3 4 5 Mr. Abed Awad residential communities like Park Slope, Prospect Heights, Pacific Park BID B63 and bustling Downtown to the peaceful Prospect Park and beyond Mr. Scott Domansky 4TH AVENUE B41 with a slew of transportation links and the Avenue traveling from the B65 BARCLAYS Mr. Chris King Manhattan Bridge to the bay. B67 CENTER Mr. Matthew Pintchik Over the years, the members of the NFBID Board of Directors, BERGEN ST ATLANTIC AVENUE Mr. -

The Bishop, the Coach & the Mayor

Saint Mary's College of California Saint Mary's Digital Commons Scholarship, Research, Creative Activities, and Interdisciplinary Works Community Engagement Spring 2014 The Bishop, The Coach & The Mayor: Three Characters in College History L. Raphael Patton FSC Saint Mary's College of California, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.stmarys-ca.edu/collaborative-works Repository Citation Patton, L. Raphael FSC. The Bishop, The Coach & The Mayor: Three Characters in College History (2014). [article]. https://digitalcommons.stmarys-ca.edu/collaborative-works/49 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship, Research, Creative Activities, and Community Engagement at Saint Mary's Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Interdisciplinary Works by an authorized administrator of Saint Mary's Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The Bishop, The Coach & The Mayor Three characters in College history Saint Mary’s College 2 3 The Bishop: Alemany and his college Preface 5 Introduction 7 1 California 9 2 Spain 17 3 Church 21 4 San Francisco 27 5 The Vicar General 33 6 Italy 41 7 Later Years 45 8 The end 49 Appendices 55 Saint Mary’s College 4 5 Preface The history of the Church in California, the history of Saint Mary’s College and the story of the Dominicans on the West Coast have each been written and rewritten, supported by impressive scholarship. Archives, newspaper morgues and libraries have been mined for material. -

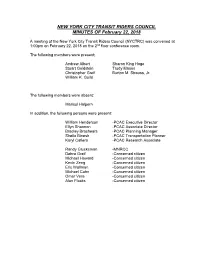

NYCTRC Minutes 2.22.18 W Presentation

NEW YORK CITY TRANSIT RIDERS COUNCIL MINUTES OF February 22, 2018 A meeting of the New York City Transit Riders Council (NYCTRC) was convened at 1:00pm on February 22, 2018 on the 2nd floor conference room. The following members were present: Andrew Albert Sharon King Hoge Stuart Goldstein Trudy Mason Christopher Greif Burton M. Strauss, Jr. William K. Guild The following members were absent: Marisol Halpern In addition, the following persons were present: William Henderson -PCAC Executive Director Ellyn Shannon -PCAC Associate Director Bradley Brashears -PCAC Planning Manager Sheila Binesh -PCAC Transportation Planner Karyl Cafiero -PCAC Research Associate Randy Glucksman -MNRCC Debra Greif -Concerned citizen Michael Howard -Concerned citizen Kevin Zeng -Concerned citizen Eric Wollman -Concerned citizen Michael Cohn -Concerned citizen Omar Vera -Concerned citizen Alan Flacks -Concerned citizen NYCTRC MINUTES -2 - Time Point Video Part 1 00:04 Approval of Agenda The agenda for the February 22, 2018 Meeting were approved. Approval of Minutes The minutes of the January 25, 2018 meeting were approved as 00:56 amended with corrections 01:51 Chair’s Report (The Chair’s Report is attached to minutes.) 03:24 A. Albert: Paying bus ridership is down, slow buses, Andy Byford’s customer focus, L train closure 06:30 T. Mason: Unclear/improper announcements communications 09:08 New MTA graphics discussion. 10:26 Introduction of Presenter: Sam Schwartz of MoveNY and FixNYC presents on Congestion Pricing proposal. 20:10 A. Albert: Bloomberg Plan only charged people entering across the East River or across northern cordon, while FixNYC allows for some free entry to FDR Drive. -

Re:C Ons T R U C T

RE:CONSTRUCTION Alliance for Downtown New York, Inc. 120 Broadway, Suite 3340 New York, New York 10271 The mission of the Alliance for Downtown New York is to provide service, advocacy, research and information to advance Lower Manhattan as a global model of the 21st Century Central Business District for the businesses, residents and visitors. www.DowntownNY.com RE:CONSTRUCTION Portrait of Progress in Lower Manhattan 2 From the Chairman and President Lower Manhattan is in a constant state of reinvention. It is a neighborhood synonymous with progress and renewal. More than 400 years of history have shown that Lower Manhattan is a wellspring of innovation, resilience, and resounding achievement. It has always creatively “reconstructed” itself as it adapts to new peoples, new challenges, new technologies, and the unforeseen. In the dozen years since September 11, 2001, Lower Manhattan is experiencing another renaissance. Over these last 12 years, private and public entities have invested $30 billion in Lower Manhattan. While this monumental investment is adding incredible dynamism to our already swiftly evolving neighborhood, it has also created a set of temporary challenges as 70 significant construction projects have been launched in a densely packed district. In response, the Downtown Alliance asked: how do we harness the tumult and create something positive and beautiful for the 60,000 people who call Lower Manhattan home, the hundreds of thousands who work here, and the millions who come and visit? The answer: Re:Construction, a groundbreaking initiative that recasts construction barriers as large-scale canvases for temporary public art. Amid the hustle and bustle of fast-changing Lower Manhattan, since 2007 the Re:Construction program has unveiled nearly 40 works of art—making our sidewalks more user-friendly, our streetscape more scenic, and integrating thought-provoking and delightful art into the pedestrian experience. -

Weinshall and Mihaltses: Testimony Before

NEW YORK STATE ASSEMBLY STANDING COMMITTEE ON LIBRARIES AND EDUCATION TECHNOLOGY ANNUAL BUDGET OVERSIGHT HEARING ON FUNDING PUBLIC LIBRARIES January 10, 2018 Good morning. My name is Iris Weinshall and I am the Chief Operating and Chief Financial Officer and Treasurer of the New York Public Library (NYPL). I am joined by George Mihaltses, Vice President for Government and Community Affairs. I would like to extend a warm welcome to new Chairwoman Didi Barrett and a thank you to all of the members of the New York State Assembly Standing Committee on Libraries and Education Technology for the invitation to testify today. We are grateful for the opportunity to speak on behalf of our millions of patrons and to emphasize the importance of State funding to successfully deliver all the programs and services we offer. Who We Are Founded in 1895, the NYPL is the nation’s largest public library system, including 88 neighborhood branches across The Bronx, Manhattan, and Staten Island and four world- renowned research facilities: The Stephen A. Schwarzman Building on 5th Avenue, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, the Science, Industry, and Business Library in Mid-Manhattan, and the Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center. Our collections hold approximately 45.2 million research items and just over 23.8 million circulating materials. In Fiscal Year 2017, NYPL hosted over 18 million visits and offered over 93,000 programs to nearly 2 million attendees. Why Our Services Matter More Than Ever Your increase in support over the last several years demonstrates that you know our services matter more now than ever. -

Staten Island, New York Draft Master Plan March 2006

FRESH KILLS PARK: LIFESCAPE STATEN ISLAND, NEW YORK DRAFT MASTER PLAN MARCH 2006 FRESH KILLS PARK: DRAFT MASTER PLAN MARCH 2006 prepared for: THE CITY OF NEW YORK Michael R. Bloomberg, Mayor NEW YORK CITY DEPARTMENT OF CITY PLANNING Amanda M. Burden, Director New York City Department of Parks & Recreation New York City Department of Sanitation New York City Department of Cultural Affairs New York City Department of Transportation Offi ce of the Staten Island Borough President New York State Department of State New York State Department of Environmental Conservation New York State Department of Transportation Municipal Art Society prepared by: FIELD OPERATIONS 475 Tenth Avenue, 10th Floor New York, New York 10018 212.433.1450 in collaboration with: Hamilton, Rabinovitz & Alschuler AKRF, Inc. Applied Ecological Services Arup GeoSyntec Skidmore, Owings & Merrill Stan Allen Architect L’Observatoire International Tomato Richard Lynch Curry & Kerlinger Mierle Laderman Ukeles The New York Department of State, through the Division of Coastal Resources, has provided funding for the Fresh Kills Park Master Plan under Title 11 of the Environmental Protection Fund for further information: www.nyc.gov/freshkillspark Fresh Kills Park Hotline: 212.977.5597, ex.275 New York City Representative: 311 or 212.NEW.YORK Community Advisory Group James P. Molinaro, President, Borough of Staten Island Michael McMahon, Councilman, City of New York James Oddo, Councilman, City of New York Andrew Lanza, Councilman, City of New York Linda Allocco, Executive Director, -

Board Committee Documents Facilities Planning And

BOARD OF TRUSTEES THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK COMMITTEE ON MINUTES OF THE MEETING FACILITIES PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT JUNE 7, 2010 The meeting was called to order at 4:07 p.m. There were present: Committee Members: University Staff: Hon. Freida D. Foster, Chair Chancellor Matthew Goldstein Hon. Jeffrey S. Wiesenfeld, Vice Chair Executive Vice Chancellor and Chief Operating Hon. Wellington Chen Officer Allan Dobrin Hon. Rita DiMartino Vice Chancellor Iris Weinshall Hon. Charles Shorter Prof. Karen Kaplowitz, faculty member Sherrie Moody, student member President Jennifer Raab, COP liaison Ex-officio: Hon. Benno Schmidt Hon. Philip A. Berry Trustee Observer: Hon. Manfred Philipp Trustee Staff: Senior Vice Chancellor and Secretary of the Board Jay Hershenson Senior Vice Chancellor and General Counsel Frederick Schaffer Deputy to the Secretary Hourig Messerlian Mr. Steven Quinn Cal. No. DISPOSITION The agenda items were considered in the following order: I. ACTION ITEMS: A. APPROVAL OF THE MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF APRIL 7, 2010. The minutes were unanimously approved as submitted. B. POLICY CALENDAR 1. Brooklyn College – Campus-Wide Fire Alarm and Security System Upgrades: Vice Chancellor Iris Weinshall stated that because of the building expansion across the campus the existing alarm systems need to be expanded and upgraded to be brought up to code. Work includes a feasibility study, a new central command station in Ingersol Halls and an insulation of new infrastructure for the fire alarm system. 2. Hostos Community College – 475 Grand Concourse ADA Renovation Project: Vice Chancellor Weinshall stated that when the college took over this former tire factor in the 1970s, it did very few renovations. -

Marathon Men Cara Alwill Leyba, a Bay Ridge Author, Gets a Kick from Her Champagne Diet

INSIDE: PAGES AND PAGES OF COUPONS TO SAVE YOU CASH! Yo u r Neighborhood — Yo u r News® BrooklynPaper.com • (718) 260–2500 • Brooklyn, NY • ©2011 Serving Brownstone Brooklyn, Williamsburg & Bay Ridge AWP/14 pages • Vol. 34, No. 45 • November 11–17, 2011 • FREE THE GOLDEN RULE Ridge lawmaker vetoes street parking permit plan By Daniel Bush publican-controlled state Senate. fectively killing the bill, which is being bany,” said an Albany source with The Brooklyn Paper State Sen. Marty Golden (R–Bay pushed by state Sen. Daniel Squadron knowledge of the GOP leadership’s The City Council overwhelmingly Ridge) is leading the fight against the (D–Brooklyn Heights) and Assembly- discussion of the so-called “residen- approved a controversial plan last Thurs- idea of charging for residential street woman Joan Millman (D–Cobble Hill) tial parking permit” proposal, which day to sell parking permits to neigh- parking, calling it a tax for something as a way of deal with the parking mess passed the Council on Nov. 3 . bors of the Barclays Center arena — that has always been free. expected when the 19,000-seat basket- The Council’s 40–8 vote came after but days later the proposal got stuck in An Albany source said that the GOP- ball arena opens next year. supporters testified that the measure the ultimate legislative pothole, the Re- led Senate would defer to Golden, ef- “This law is dead on arrival in Al- See PARKING on page 2 Community Newspaper Group / Dan MacLeod Marathon men Cara Alwill Leyba, a Bay Ridge author, gets a kick from her champagne diet. -

DECEMBER 2018 Volume 32 Number 2 Keeping You up to Date on SALES, HAPPENINGS Our Town & PEOPLE • • • • • • in Our Town - St

PRSRT STD **********************************ECRWSS US Postage PAID St. James NY POSTAL CUSTOMER Permit No. 10 DECEMBER 2018 Volume 32 Number 2 Keeping you up to date on SALES, HAPPENINGS Our Town & PEOPLE • • • • • • In Our Town - St. James S T J A M E S PUBLISHED MONTHLY Peace Wishing one & all a new year filled with love, respect, humility, compassion, tolerance, inclusion, good health and good will. Thank You for your continued support! – 2– 400 North Country Rd. St. James, NY 11780 At the Intersection of Edgewood Ave. and NorthCountry Rd. 631-724-5425 Come visit our Christmas Wonderland! Fresh Cut Christmas trees S Christmas Lights S Ornaments S Holiday Décor S Wreaths S Unique Gifts S Candles and much more! COmpLETE GarDEn CEnTEr Huge Selection of lawn & Yard toolS • rakes • Shovels • leaf Bags & more! HoMeownerS and ContraCtorS welCoMe! FULLY STOCKED SEASONED For All Your Snow Clean-Up Needs! FIREWOOD Ice Melt, Salt, Shovels, etc. Pick-up or delivery Fall Clean-UpS • Fall plantIngS MaIntenanCe ContraCtS • CaLL TODaY • www.Mazelislandscape.com to schedule your 631-724-5425 Landscape Design Project OUR TOWN • DECEMBER 2018 – 3– IN THIS ISSUE MERCHANT SPOTLIGHT Our Town Gray’s Jewelers ....................................................4 HOLIDAY HAPPENINGS S • T • J • A • M • E • S Christmas Tree Lighting Extravaganza ................6 Menorah Lighting ..................................................8 St. James Lutheran Church STAFF Worship Schedule ..............................................10 Ruth Garthe . Editor AROUND TOWN Robin Clark . .Associate Editor St. James Lutheran Church Hosts Grief Share ..12 Celebrate St. James: Past - Present - Future Events ....................12 Elizabeth Isabelle . Feature Writer Scouts Collect Candy for Our Troops ............................................14 William Garthe . Advertising Celebrate St. -

Board Committee Documents Executive Minutes July 22, 2014

BOARD OF TRUSTEES THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE MINUTES OF THE MEETING JULY 22, 2014 The meeting was called to order at 5:30 p.m. There were present: Committee Members: University Staff: Chairperson Benno Schmidt, Chair Chancellor James B. Milliken Vice Chairperson Philip A. Berry, Vice Chair Executive Vice Chancellor and Chief Operating Hon. Wellington Z. Chen Officer Allan H. Dobrin Hon. Freida D. Foster Senior Advisor to the Chancellor for Fiscal Policy Hon. Joseph J. Lhota Marc V. Shaw Hon. Carol A. Robles-Roman Vice Chancellor Matthew Sapienza Vice Chancellor Pamela Silverblatt Trustee Observers: Vice Chancellor Gillian Small Hon. Terrence Martell Vice Chancellor Iris Weinshall Hon. Muhammad W. Arshad Associate Vice Chancellor Andrea Shapiro Davis Senior University Dean for the Executive Office Trustee Staff: and Enrollment Robert Ptachik Senior Vice Chancellor and Secretary of the Deputy General Counsel Jane Sovern Board Jay Hershenson Deputy to the Secretary Hourig Messerlian Ms. Towanda Lewis Cal. No. DISPOSITION Chairperson Benno Schmidt announced that CUNY-TV is making available this important community service by transmitting the Public Session of this afternoon’s meeting of the Board of Trustees live on cable Channel 75. The meeting is also being webcast live at www.cuny.edu/livestream providing service worldwide through personal computers and mobile devices. The Public Session of this meeting will be available as a podcast within 24 hours and can be accessed through the CUNY website. Chairperson Schmidt stated that on behalf of the entire Board, he would like to warmly congratulate Vice Chancellor Iris Weinshall on her appointment at the New York Public Library as its Chief Operations Officer. -

The Taxpayer As Reformer: 'Pocketbook Politics' and the Law, 1860--1940

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2009 The taxpayer as reformer: 'Pocketbook politics' and the law, 1860--1940 Linda Upham-Bornstein University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Upham-Bornstein, Linda, "The taxpayer as reformer: 'Pocketbook politics' and the law, 1860--1940" (2009). Doctoral Dissertations. 491. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/491 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE TAXPAYER AS REFORMER: 'POCKETBOOK POLITICS' AND THE LAW, 1860 -1940 BY LINDA UPHAM-BORNSTEIN Baccalaureate Degree (BA), University of Massachusetts, Boston, 1977 Master's Degree, University of New Hampshire, 2001 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History May, 2009 UMI Number: 3363735 Copyright 2009 by Upham-Bornstein, Linda INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion.