Hypergeorgism: When Rent Taxation Is Socially Optimal∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Lectures on Urban Economics

2020 Lectures on Urban Economics Lecture 5: Cities in Developing Countries J. Vernon Henderson (LSE) 9 July 2020 Outline of talk • Urbanization: Moving to cities • Where are the frontiers of urbanization • Does the classic framework apply? • “Spatial equilibrium” in developing countries • Issues and patterns • Structural modelling • Data needed • Relevant questions and revisions to baseline models • Within cities • Building the city: investment in durable capital • Role of slums • Land and housing market issues Frontiers of urbanization • Not Latin America and not much of East and West Asia • (Almost) fully urbanized (60-80%) with annual rate of growth in urban share growth typically about 0.25% • Focus is on clean-up of past problems or on distortions in markets • Sub-Saharan Africa and South and South-East Asia • Urban share 35-50% and annual growth rate in that share of 1.2- 1.4% • Africa urbanizing at comparatively low-income levels compared to other regions today or in the past (Bryan at al, 2019) • Lack of institutions and lack of money for infrastructure “needs” Urbanizing while poor Lagos slums, today Sewers 1% coverage London slums, 120 years ago Sewer system: 1865 Models of urbanization • Classic dual sector • Urban = manufacturing; rural = agriculture • Structural transformation • Closed economy: • Productivity in agriculture up, relative to limited demand for food. • Urban sector with productivity growth in manufacturing draws in people • Open economy. • “Asian tigers”. External demand for manufacturing (can import food in theory) • FDI and productivity growth/transfer Moving to cities: bright lights or productivity? Lack of structural transformation • Most of Africa never really has had more than local non-traded manufactures. -

544 Urban Growth

544 urban growth changes in spatially delineated public goods. the physical structure of cities and how it may change as International Economic Review 45, 1047-77. cities grow. It also focuses on how changes in commuting Tolley, G. 1974. The welfare economics of city bigness. costs, as well as the industrial composition of national Journal of Urban Economics 1, 324-45. output and other technological changes, have affected the United Nations Population Division. 2004. World Population growth of cities. Another direction has focused on Prospects: The 2004 Revision Population Database. Online. understanding the evolution of systems of cities - that Available at http://esa.un.orglunpp, accessed 28 June is, how cities of different sizes interact, accommodate and 2005. share different functions as the economy develops and what the properties of the size distribution of urban areas are for economies at different stages of development. Do the properties of the system of cities and of city size urban growth distribution persist while national population is growing? Urban growth - the growth and decline of urban Finally, there is a literature that studies the link between areas - as an economic phenomenon is inextricably urban growth and economic growth. What restrictions linked with the process of urbanization. Urbanization does urban growth impose on economic growth? What itself has punctuated economic development. The spatial economic functions are allocated to cities of different distribution of economic activity, measured in terms of sizes in a growing economy? Of course, all of these lines population, output and income, is concentrated. The of inquiry are closely related and none of them may be patterns of such concentrations and their relationship fully understood, theoretically and empirically, on its to measured economic and demographic variables con own. -

Taxation of Land and Economic Growth

economies Article Taxation of Land and Economic Growth Shulu Che 1, Ronald Ravinesh Kumar 2 and Peter J. Stauvermann 1,* 1 Department of Global Business and Economics, Changwon National University, Changwon 51140, Korea; [email protected] 2 School of Accounting, Finance and Economics, Laucala Campus, The University of the South Pacific, Suva 40302, Fiji; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-55-213-3309 Abstract: In this paper, we theoretically analyze the effects of three types of land taxes on economic growth using an overlapping generation model in which land can be used for production or con- sumption (housing) purposes. Based on the analyses in which land is used as a factor of production, we can confirm that the taxation of land will lead to an increase in the growth rate of the economy. Particularly, we show that the introduction of a tax on land rents, a tax on the value of land or a stamp duty will cause the net price of land to decline. Further, we show that the nationalization of land and the redistribution of the land rents to the young generation will maximize the growth rate of the economy. Keywords: taxation of land; land rents; overlapping generation model; land property; endoge- nous growth Citation: Che, Shulu, Ronald 1. Introduction Ravinesh Kumar, and Peter J. In this paper, we use a growth model to theoretically investigate the influence of Stauvermann. 2021. Taxation of Land different types of land tax on economic growth. Further, we investigate how the allocation and Economic Growth. Economies 9: of the tax revenue influences the growth of the economy. -

Well Isnjt That Spatial?! Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Well Isn’tThat Spatial?! Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics: A View From Economic Theory Marcus Berlianty February 2005 I thank Gilles Duranton, Sukkoo Kim, Fan-chin Kung and Ping Wang for comments, implicating them only for baiting me. yDepartment of Economics, Washington University, Campus Box 1208, 1 Brookings Drive, St. Louis, MO 63130-4899 USA. Phone: (314) 935-8486, Fax: (314) 935-4156, e-mail: [email protected] 1 As a younger and more naïve reviewer of the …rst volume of the Handbook (along with Thijs ten Raa, 1994) more than a decade ago, it is natural to begin with a comparison for the purpose of evaluating the progress or lack thereof in the discipline.1 Then I will discuss some drawbacks of the New Economic Geography, and …nally explain where I think we should be heading. It is my intent here to be provocative2, rather than to review speci…c chapters of the Handbook. First, volume 4 cites Masahisa Fujita more than the one time he was cited in volume 1. Volume 4 cites Ed Glaeser more than the 4 times he was cited in volume 3. This is clear progress. Second, since the …rst volume, much attention has been paid by economists to the simple question: “Why are there cities?” The invention of the New Economic Geography represents an important and creative attempt to answer this question, though it is not the unique set of models capable of addressing it. -

The Fiscal Benefits of Stringent Climate Change Mitigation: an Overview

Climate Policy ISSN: 1469-3062 (Print) 1752-7457 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tcpo20 The fiscal benefits of stringent climate change mitigation: an overview Jan Siegmeier, Linus Mattauch, Max Franks, David Klenert, Anselm Schultes & Ottmar Edenhofer To cite this article: Jan Siegmeier, Linus Mattauch, Max Franks, David Klenert, Anselm Schultes & Ottmar Edenhofer (2017): The fiscal benefits of stringent climate change mitigation: an overview, Climate Policy, DOI: 10.1080/14693062.2017.1400943 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2017.1400943 Published online: 04 Dec 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 22 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tcpo20 Download by: [192.76.8.71] Date: 06 December 2017, At: 02:21 CLIMATE POLICY, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2017.1400943 SYNTHESIS ARTICLE The fiscal benefits of stringent climate change mitigation: an overview Jan Siegmeier a,b, Linus Mattaucha,c, Max Franksb,d, David Klenerta,b,d, Anselm Schultes b,d and Ottmar Edenhofera,b,d aMercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change, Berlin, Germany; bTechnical University of Berlin, Chair for Economics of Climate Change, Berlin, Germany; cEnvironmental Change Institute and Institute for New Economic Thinking at the Oxford Martin School, School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK; dPotsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, Potsdam, Germany ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The Paris Agreement’s very ambitious mitigation goals, notably to ‘pursue efforts’ to Carbon pricing; distributional limit warming to 1.5°C, imply that climate policy will remain a national affair for effects; policy interactions/ some time. -

810 South Sterling Ave. Tampa, FL 33609 [email protected]

810 South Sterling Ave. Tampa, FL 33609 813.289.88L.L, [email protected] - RBANECONOMICS.COM ECONOMICS INC. MICHAEL A. MCELVEEN, MAI, CCIM, CRE President Urban Economics, Inc. 810 South Sterling Avenue Tampa, FL 33609-4516 Urban Economics, Inc. - Tampa, Florida - Michael A. McElveen is president of Urban Economics, Incorporat ed, a real estate consultancy providing econometrics, valuation, spat ia l analytics, economic impact and st igma effect advice and opinions for 31 years. The focus of Michael A. McElveen has been expert witness t estimony, having testified numerous times at either a jury trial , hearing or by deposition. Mr. McElveen has been accepted by the Ninth Jud icial Circuit Court of Florida an d the Thirteenth Judicial Circuit Court as an expert in the use of econometrics in real estate. Mr. McElveen has performed the following econometric studies: • Econometric study of the marginal impact of an additional 18-hole golf course and equestrian facility o n the value of residential lots, Lake County, FL; • Sales price index trend of fractured condominium sales in O sceola County; • Econometric study of the rent effect of deficient parking at neighborhood retail centers, Charlotte County, FL; • Economet ric study of the sales price effect of location and community w aterfront in Martin County, FL; and • Hedonic regression model analysis of the sales price effect vehicul ar traffic volume and roadway elevation on nearby ho mes in Duval County, Florida. Ed uca ti o n Bachelo r of Arts Finance, University of South Bachelor of Science, Florida State University Florida Professional Associations Appraisal Institute (MAI), Certificate No. -

Working Paper No. 517 What Are the Relative Macroeconomic Merits And

Working Paper No. 517 What Are the Relative Macroeconomic Merits and Environmental Impacts of Direct Job Creation and Basic Income Guarantees? by Pavlina R. Tcherneva The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College October 2007 The Levy Economics Institute Working Paper Collection presents research in progress by Levy Institute scholars and conference participants. The purpose of the series is to disseminate ideas to and elicit comments from academics and professionals. The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, founded in 1986, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, independently funded research organization devoted to public service. Through scholarship and economic research it generates viable, effective public policy responses to important economic problems that profoundly affect the quality of life in the United States and abroad. The Levy Economics Institute P.O. Box 5000 Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 12504-5000 http://www.levy.org Copyright © The Levy Economics Institute 2007 All rights reserved. ABSTRACT There is a body of literature that favors universal and unconditional public assurance policies over those that are targeted and means-tested. Two such proposals—the basic income proposal and job guarantees—are discussed here. The paper evaluates the impact of each program on macroeconomic stability, arguing that direct job creation has inherent stabilization features that are lacking in the basic income proposal. A discussion of modern finance and labor market dynamics renders the latter proposal inherently inflationary, and potentially stagflationary. After studying the macroeconomic viability of each program, the paper elaborates on their environmental merits. It is argued that the “green” consequences of the basic income proposal are likely to emerge, not from its modus operandi, but from the tax schemes that have been advanced for its financing. -

A Macroeconomic Henry George Theorem

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Mattauch, Linus; Siegmeier, Jan; Edenhofer, Ottmar; Creutzig, Felix Working Paper Financing Public Capital through Land Rent Taxation: A Macroeconomic Henry George Theorem CESifo Working Paper, No. 4280 Provided in Cooperation with: Ifo Institute – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich Suggested Citation: Mattauch, Linus; Siegmeier, Jan; Edenhofer, Ottmar; Creutzig, Felix (2013) : Financing Public Capital through Land Rent Taxation: A Macroeconomic Henry George Theorem, CESifo Working Paper, No. 4280, Center for Economic Studies and ifo Institute (CESifo), Munich This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/77659 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Financing Public Capital through Land Rent Taxation: A Macroeconomic Henry George Theorem Linus Mattauch Jan Siegmeier Ottmar Edenhofer Felix Creutzig CESIFO WORKING PAPER NO. -

Economics Chair: Marian Manic Sai Mamunuru Halefom Belay Rosie Mueller Jan P

Economics Chair: Marian Manic Sai Mamunuru Halefom Belay Rosie Mueller Jan P. Crouter Jason Ralston Denise Hazlett Economics is the study of how people and societies choose to use scarce resources in the production of goods and services, and of the distribution of these goods and services among individuals and groups in society. The economics major requires coursework in economics and mathematics. A student who enters Whitman with no prior college-level work in either of these areas would need to complete math 125 and complete at least 35 credits in economics. Learning Goals: Upon graduation, a student will be able to demonstrate: Major-Specific Areas of Knowledge o Students should have an understanding of how economics can be used to explain and interpret a) the behavior of agents (for example, firms and households) and the markets or settings in which they interact, and b) the structure and performance of national and global economies. Students should also be able to evaluate the structure, internal consistency and logic of economic models and the role of assumptions in economic arguments. Communication o Students should be able to communicate effectively in written, spoken, graphical, and quantitative form about specific economic issues. Critical Reasoning o Students should be able to apply economic analysis to evaluate everyday problems and policy proposals and to assess the assumptions, reasoning and evidence contained in an economic argument. Quantitative Analysis o Students should grasp the mathematical logic of standard macroeconomic and microeconomic models. o Students should know how to use empirical evidence to evaluate an economic argument (including the collection of relevant data for empirical analysis, statistical analysis, and interpretation of the results of the analysis) and how to understand empirical analyses of others. -

1. Introduction : (A) What Is Public Economics? First, a Very Brief and Broad Outline of the Structure of Government Finance, Pa

1. Introduction : (a) What is Public Economics? First, a very brief and broad outline of the structure of government finance, particularly government revenue sources, in Canada. In other words, \what level of government levies what tax, and how important are the different taxes?". Before that, an important message. This course is a fourth{year level course. The pre- requisites are intermediate microeconomics, and intermediate macroeconomics : AP/ECON 2300, 2350, 2400 and 2450, or their equivalents. Those prerequisites are meant to be taken seriously. In particular, you will find out very soon that this course is a course in the application of microe- conomic theory. It is microeconomic theory applied to taxation. Some of the concepts used in Econ 2300 and 2350 are going to get used here again | every day. Indifference curves, income and substitution effects, general equilibrium prices : these will keep popping up. So this is a double warning : (i) you have to have the formal prerequisites in order to get in to the course, and (ii) the course content is going to keep reminding you of material from Econ 2300 and 2350. Why is this course full of microeconomic theory? Because economists think that the concepts of microeconomic theory are useful in analyzing the behaviour of consumers and workers and firms and voters. And because much of the subject matter of the course is the effects of taxation on the behaviour of these economic agents, and the analysis of how the behaviour of these economic agents should affect the government's choices of taxes. Why microeconomics? After all, there is something pretty public about most of the material in macroeconomics. -

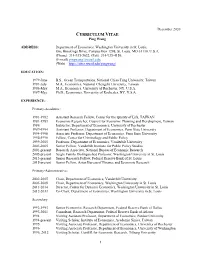

CURRICULUM VITAE Ping Wang

December 2020 CURRICULUM VITAE Ping Wang ADDRESS: Department of Economics, Washington University in St. Louis, One Brookings Drive, Campus Box 1208, St. Louis, MO 63130, U.S.A. (Phone) 314-935-5632; (Fax) 314-935-4156; (E-mail) [email protected]; (Web) https://sites.wustl.edu/pingwang/ EDUCATION: 1979-June B.S., Ocean Transportation, National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan 1981-July M.A., Economics, National Chengchi University, Taiwan 1986-May M.A., Economics, University of Rochester, NY, U.S.A. 1987-May Ph.D., Economics, University of Rochester, NY, U.S.A. EXPERIENCE: Primary-Academic: 1981-1982 Assistant Research Fellow, Center for the Quality of Life, TAIWAN 1981-1983 Economic Researcher, Council for Economic Planning and Development, Taiwan 1986 Instructor, Department of Economics, University of Rochester 1987-1994 Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, Penn State University 1994-1998 Associate Professor, Department of Economics, Penn State University 1994-1998 Fellow, Center for Criminology and Public Policy 1999-2005 Professor, Department of Economics, Vanderbilt University 2001-2005 Senior Fellow, Vanderbilt Institute for Public Policy Studies 2001-present Research Associate, National Bureau of Economic Research 2005-present Seigle Family Distinguished Professor, Washington University in St. Louis 2013-present Senior Research Fellow, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 2015-present Senior Fellow, Asian Bureau of Finance and Economic Research Primary-Administrative: 2002-2005 Chair, Department of Economics, Vanderbilt University -

Economics 230A Public Sector Microeconomics

University of California, Berkeley Professor Alan Auerbach Department of Economics 525 Evans Hall Fall 2005 3-0711; auerbach@econ ECONOMICS 230A PUBLIC SECTOR MICROECONOMICS This is the first of two courses in the Public Economics sequence. It will cover core material on taxation, public expenditures and public choice, and conclude with a consideration of the effects of capital income taxation on the behavior of households and firms. Economics 230B, the second semester in the sequence, will extend the discussion of optimal income taxation and consider more fully the behavioral effects of government policy and the institutional characteristics of important U.S. federal taxes and expenditure programs Class meetings: Tuesdays 9-11, 639 Evans Hall Office hours: Mondays, 10:00-11:30, and by appointment Prerequisites: This course should normally be taken after the completion of first-year Ph. D. courses in economic theory and econometrics. Requirements: Problem sets (2) - 30% Paper (5 page review) - 20% Final examination - 50% There is no required textbook for this course. All starred readings below are required and are either included in the course reader or, where noted, available on the web. Non-starred material will be useful for further reading on topics of interest and preparation for the public economics field examination. The following texts and collections, selections from which appear on the reading list, are also useful for background reference: A. Atkinson and J. Stiglitz, Lectures on Public Economics, McGraw-Hill (1980) A. Auerbach and M. Feldstein, eds., Handbook of Public Economics, North-Holland, vol. 1 (1985), vol. 2 (1987), vol. 3 (2002) and vol.