544 Urban Growth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Lectures on Urban Economics

2020 Lectures on Urban Economics Lecture 5: Cities in Developing Countries J. Vernon Henderson (LSE) 9 July 2020 Outline of talk • Urbanization: Moving to cities • Where are the frontiers of urbanization • Does the classic framework apply? • “Spatial equilibrium” in developing countries • Issues and patterns • Structural modelling • Data needed • Relevant questions and revisions to baseline models • Within cities • Building the city: investment in durable capital • Role of slums • Land and housing market issues Frontiers of urbanization • Not Latin America and not much of East and West Asia • (Almost) fully urbanized (60-80%) with annual rate of growth in urban share growth typically about 0.25% • Focus is on clean-up of past problems or on distortions in markets • Sub-Saharan Africa and South and South-East Asia • Urban share 35-50% and annual growth rate in that share of 1.2- 1.4% • Africa urbanizing at comparatively low-income levels compared to other regions today or in the past (Bryan at al, 2019) • Lack of institutions and lack of money for infrastructure “needs” Urbanizing while poor Lagos slums, today Sewers 1% coverage London slums, 120 years ago Sewer system: 1865 Models of urbanization • Classic dual sector • Urban = manufacturing; rural = agriculture • Structural transformation • Closed economy: • Productivity in agriculture up, relative to limited demand for food. • Urban sector with productivity growth in manufacturing draws in people • Open economy. • “Asian tigers”. External demand for manufacturing (can import food in theory) • FDI and productivity growth/transfer Moving to cities: bright lights or productivity? Lack of structural transformation • Most of Africa never really has had more than local non-traded manufactures. -

Well Isnjt That Spatial?! Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Well Isn’tThat Spatial?! Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics: A View From Economic Theory Marcus Berlianty February 2005 I thank Gilles Duranton, Sukkoo Kim, Fan-chin Kung and Ping Wang for comments, implicating them only for baiting me. yDepartment of Economics, Washington University, Campus Box 1208, 1 Brookings Drive, St. Louis, MO 63130-4899 USA. Phone: (314) 935-8486, Fax: (314) 935-4156, e-mail: [email protected] 1 As a younger and more naïve reviewer of the …rst volume of the Handbook (along with Thijs ten Raa, 1994) more than a decade ago, it is natural to begin with a comparison for the purpose of evaluating the progress or lack thereof in the discipline.1 Then I will discuss some drawbacks of the New Economic Geography, and …nally explain where I think we should be heading. It is my intent here to be provocative2, rather than to review speci…c chapters of the Handbook. First, volume 4 cites Masahisa Fujita more than the one time he was cited in volume 1. Volume 4 cites Ed Glaeser more than the 4 times he was cited in volume 3. This is clear progress. Second, since the …rst volume, much attention has been paid by economists to the simple question: “Why are there cities?” The invention of the New Economic Geography represents an important and creative attempt to answer this question, though it is not the unique set of models capable of addressing it. -

810 South Sterling Ave. Tampa, FL 33609 [email protected]

810 South Sterling Ave. Tampa, FL 33609 813.289.88L.L, [email protected] - RBANECONOMICS.COM ECONOMICS INC. MICHAEL A. MCELVEEN, MAI, CCIM, CRE President Urban Economics, Inc. 810 South Sterling Avenue Tampa, FL 33609-4516 Urban Economics, Inc. - Tampa, Florida - Michael A. McElveen is president of Urban Economics, Incorporat ed, a real estate consultancy providing econometrics, valuation, spat ia l analytics, economic impact and st igma effect advice and opinions for 31 years. The focus of Michael A. McElveen has been expert witness t estimony, having testified numerous times at either a jury trial , hearing or by deposition. Mr. McElveen has been accepted by the Ninth Jud icial Circuit Court of Florida an d the Thirteenth Judicial Circuit Court as an expert in the use of econometrics in real estate. Mr. McElveen has performed the following econometric studies: • Econometric study of the marginal impact of an additional 18-hole golf course and equestrian facility o n the value of residential lots, Lake County, FL; • Sales price index trend of fractured condominium sales in O sceola County; • Econometric study of the rent effect of deficient parking at neighborhood retail centers, Charlotte County, FL; • Economet ric study of the sales price effect of location and community w aterfront in Martin County, FL; and • Hedonic regression model analysis of the sales price effect vehicul ar traffic volume and roadway elevation on nearby ho mes in Duval County, Florida. Ed uca ti o n Bachelo r of Arts Finance, University of South Bachelor of Science, Florida State University Florida Professional Associations Appraisal Institute (MAI), Certificate No. -

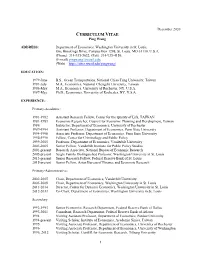

CURRICULUM VITAE Ping Wang

December 2020 CURRICULUM VITAE Ping Wang ADDRESS: Department of Economics, Washington University in St. Louis, One Brookings Drive, Campus Box 1208, St. Louis, MO 63130, U.S.A. (Phone) 314-935-5632; (Fax) 314-935-4156; (E-mail) [email protected]; (Web) https://sites.wustl.edu/pingwang/ EDUCATION: 1979-June B.S., Ocean Transportation, National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan 1981-July M.A., Economics, National Chengchi University, Taiwan 1986-May M.A., Economics, University of Rochester, NY, U.S.A. 1987-May Ph.D., Economics, University of Rochester, NY, U.S.A. EXPERIENCE: Primary-Academic: 1981-1982 Assistant Research Fellow, Center for the Quality of Life, TAIWAN 1981-1983 Economic Researcher, Council for Economic Planning and Development, Taiwan 1986 Instructor, Department of Economics, University of Rochester 1987-1994 Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, Penn State University 1994-1998 Associate Professor, Department of Economics, Penn State University 1994-1998 Fellow, Center for Criminology and Public Policy 1999-2005 Professor, Department of Economics, Vanderbilt University 2001-2005 Senior Fellow, Vanderbilt Institute for Public Policy Studies 2001-present Research Associate, National Bureau of Economic Research 2005-present Seigle Family Distinguished Professor, Washington University in St. Louis 2013-present Senior Research Fellow, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 2015-present Senior Fellow, Asian Bureau of Finance and Economic Research Primary-Administrative: 2002-2005 Chair, Department of Economics, Vanderbilt University -

Place-Based Policies

CHAPTER 18 Place-Based Policies David Neumark*, Helen Simpson† *UCI, NBER, and IZA, Irvine, CA, USA †University of Bristol, CMPO, OUCBT and CEPR, Bristol, UK Contents 18.1. Introduction 1198 18.2. Theoretical Basis for Place-Based Policies 1206 18.2.1 Agglomeration economies 1206 18.2.2 Knowledge spillovers and the knowledge economy 1208 18.2.3 Industry localization 1209 18.2.4 Spatial mismatch 1210 18.2.5 Network effects 1211 18.2.6 Equity motivations for place-based policies 1212 18.2.7 Summary and implications for empirical analysis 1213 18.3. Evidence on Theoretical Motivations and Behavioral Hypotheses Underlying Place-Based Policies 1215 18.3.1 Evidence on agglomeration economies 1215 18.3.2 Is there spatial mismatch? 1217 18.3.3 Are there important network effects in urban labor markets? 1219 18.4. Identifying the Effects of Place-Based Policies 1221 18.4.1 Measuring local areas where policies are implemented and economic outcomes in those areas 1222 18.4.2 Accounting for selective geographic targeting of policies 1222 18.4.3 Identifying the effects of specific policies when areas are subject to multiple interventions 1225 18.4.4 Accounting for displacement effects 1225 18.4.5 Studying the effects of discretionary policies targeting specific firms 1226 18.4.6 Relative versus absolute effects 1229 18.5. Evidence on Impacts of Policy Interventions 1230 18.5.1 Enterprise zones 1230 18.5.1.1 The California enterprise zone program 1230 18.5.1.2 Other recent evidence for US state-level and federal programs 1237 18.5.1.3 Evidence from other countries 1246 18.5.1.4 Summary of evidence on enterprise zones 1249 18.5.2 Place-based policies that account for network effects 1250 18.5.3 Discretionary grant-based policies 1252 18.5.3.1 Summary of evidence on discretionary grants 1259 18.5.4 Clusters and universities 1261 18.5.4.1 Clusters policies 1261 18.5.4.2 Universities 1264 18.5.4.3 Summary of evidence on clusters and universities 1267 Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics,Volume5B © 2015 Elsevier B.V. -

Hypergeorgism: When Rent Taxation Is Socially Optimal∗

Hypergeorgism: When rent taxation is socially optimal∗ Ottmar Edenhoferyz, Linus Mattauch,x Jan Siegmeier{ June 25, 2014 Abstract Imperfect altruism between generations may lead to insufficient capital accumulation. We study the welfare consequences of taxing the rent on a fixed production factor, such as land, in combination with age-dependent redistributions as a remedy. Taxing rent enhances welfare by increasing capital investment. This holds for any tax rate and recycling of the tax revenues except for combinations of high taxes and strongly redistributive recycling. We prove that specific forms of recycling the land rent tax - a transfer directed at fundless newborns or a capital subsidy - allow reproducing the social optimum under pa- rameter restrictions valid for most economies. JEL classification: E22, E62, H21, H22, H23, Q24 Keywords: land rent tax, overlapping generations, revenue recycling, social optimum ∗This is a pre-print version. The final article was published at FinanzArchiv / Public Finance Analysis, doi: 10.1628/001522115X14425626525128 yAuthors listed in alphabetical order as all contributed equally to the paper. zMercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change, Techni- cal University of Berlin and Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. E-Mail: [email protected] xMercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change. E-Mail: [email protected] {(Corresponding author) Technical University of Berlin and Mercator Research Insti- tute on Global Commons and Climate Change. Torgauer Str. 12-15, D-10829 Berlin, E-Mail: [email protected], Phone: +49-(0)30-3385537-220 1 1 INTRODUCTION 2 1 Introduction Rent taxation may become a more important source of revenue in the future due to potentially low growth rates and increased inequality in wealth in many developed economies (Piketty and Zucman, 2014; Demailly et al., 2013), concerns about international tax competition (Wilson, 1986; Zodrow and Mieszkowski, 1986; Zodrow, 2010), and growing demand for natural resources (IEA, 2013). -

Regional Science and Urban Economics

REGIONAL SCIENCE AND URBAN ECONOMICS AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Audience p.1 • Impact Factor p.1 • Abstracting and Indexing p.2 • Editorial Board p.2 • Guide for Authors p.4 ISSN: 0166-0462 DESCRIPTION . Regional Science and Urban Economics facilitates and encourages high-quality scholarship on important issues in regional and urban economics. It publishes significant contributions that are theoretical or empirical, positive or normative. It solicits original papers with a spatial dimension that can be of interest to economists. Empirical papers studying causal mechanisms are expected to propose a convincing identification strategy. Benefits to authors We also provide many author benefits, such as free PDFs, a liberal copyright policy, special discounts on Elsevier publications and much more. Please click here for more information on our author services. Please see our Guide for Authors for information on article submission. If you require any further information or help, please visit our Support Center AUDIENCE . Regional Economists, Urban Economists, Environmental Economists, Economic Geographers. IMPACT FACTOR . 2020: 2.613 © Clarivate Analytics Journal Citation Reports 2021 AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK 1 Oct 2021 www.elsevier.com/locate/regec 1 ABSTRACTING AND INDEXING . Documentation Economique International Development Abstracts Current Contents Journal of Economic Literature Engineering Village - GEOBASE Social Sciences Citation Index Sociological Abstracts ABI/Inform Journal of Economic Literature Environmental Periodicals Bibliography Journal of Regional Science Sage Urban Studies Abstracts UMI Data Courier Journal of Planning Literature RePEc EDITORIAL BOARD . Editors G. Ahlfeldt, The London School of Economics and Political Science, London, United Kingdom L. Gobillon, Paris School of Economics, Paris, France Co-Editors M. -

Cities and Climate Change

Cities and Climate Change POLICY HIGHLIGHTSPERSPECTIVES National governments enabling local action BETTER POLICIESBloomberg FOR BETTER LIVES Philanthropies This Policy Perspectives was jointly prepared by the OECD and Bloomberg Philanthropies as an input to the OECD Leaders Seminar with Michael R. Bloomberg, UN Special Envoy for Cities and Climate Change. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. On the eve of the UN Climate Summit, The steps cities take now to combat and as we approach COP 21 in climate change will have a major Paris next year, it is urgent that we impact on the future of our planet. get onto a path towards zero net Cities have shown they have the emissions from fossil fuels in the capacity and the will to meet this second half of the century so that we challenge. can meet the 2-degree goal. Solid partnerships between cities and Michael R. Bloomberg, national governments are an essential United Nations Special Envoy first step to tackling this challenge, for Cities and Climate Change given the key role cities play in both “mitigating and adapting to climate change. Angel Gurría, OECD Secretary-General 2 . © OECD CITIES AND CLIMATE CHANGE POLICY PERSPECTIVES September 2014 This Policy Perspectives explores how enabling policy frameworks at the national level can support critical urban action to combat climate change. Key Messages • Cities have a unique ability to address global climate change challenges. Choices made in cities today about long-lived urban infrastructure will determine the extent and impact of climate change, our ability to achieve emission reductions and our capacity to adapt to changing circumstances. -

Financing Green Urban Infrastructure

Financing Green Urban Infrastructure Merk, O., Saussier, S., Staropoli, C., Slack, E., Kim, J-H (2012), ―Financing Green Urban Infrastructure‖, OECD Regional Development Working Papers 2012/10, OECD Publishing; http://dc.doi.org/10.1787/5k92p0c6j6r0-en OECD Regional Development Working Papers 2012/10 ABSTRACT This paper presents an overview of practices and challenges related to financing green sustainable cities. Cities are essential actors in stimulating green infrastructure; and urban finance is one of the promising ways in which this can be achieved. Cities are key investors in infrastructure with green potential, such as buildings, transport, water and waste. Their main revenue sources, such as property taxes, transport fees and other charges, are based on these same sectors; cities thus have great potential to ―green‖ their financial instruments. At the same time, increased public constraints call for a mobilisation of new sources of finance and partnerships with the private sector. This working paper analyses several of these sources: public-private partnerships, tax-increment financing, development charges, value-capture taxes, loans, bonds and carbon finance. The challenge in mobilising these instruments is to design them in a green way, while building capacity to engage in real co-operative and flexible arrangements with the private sector. Keywords: infrastructure finance, urban infrastructure, urban development, urban finance, private finance, public-private partnerships, green growth 2 FOREWORD This paper was produced in co-operation with la Fabrique de la Cité/ The City Factory (VINCI) and was approved by the 14th session of the OECD Working Party on Urban Areas, 6 December 2011. The report has been produced and co-ordinated by Olaf Merk, under responsibility of Lamia Kamal-Chaoui (Head of OECD Urban Unit) and Joaquim Oliveira Martins (Head of OECD Regional Development Policy Division). -

Syllabus - ECON 137 – Urban & Regional Economics Summer 2006 (Session C)

Syllabus - ECON 137 – Urban & Regional Economics Summer 2006 (session C) Instructor: Guillermo Ordonez ([email protected]) Lecture hours: Monday and Wednesday 1:00 – 3:05pm, Room: Dodd 175 Office hours: Monday and Wednesday 3:30 – 4:30pm, Room: Bunche 2265 Webpage: http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/061/econ137-1/ UCLA campus “A city within a city” (UCLA undergraduate admission webpage) “A great city is not to be confounded with a populous one” Aristotle (Ancient Greek Philosopher, 384 BC-322 BC) “Los Angeles is 72 suburbs in search of a city” Dorothy Parker (American short- story writer and poet, 1893-1967) “What I like about cities is that everything is king size, the beauty and the ugliness.” Joseph Brodsky (Russian born American Poet and Writer. Nobel Prize for Literature in 1987. 1940- 1996) Course description In this class we will study the economics of cities and urban problems by understanding the effects of geographic location on the decisions of individuals and firms. The importance of location in everyday choices is easily assessed from our day-to- day lives (especially living in LA!), yet traditional microeconomic models are spaceless, (i.e we do not account for geographic factors). First we will try to answer general and interesting questions such as, Why do cities exist? How do firms decide where to locate? Why do people live in cities? What determines the growth and size of a city? Which policies can modify the shape of a city? Having discussed why we live in cities, we will analyze the economic problems that arise because we are living in cities. -

Journal of Urban Economics

JOURNAL OF URBAN ECONOMICS AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Impact Factor p.1 • Abstracting and Indexing p.1 • Editorial Board p.2 • Guide for Authors p.4 ISSN: 0094-1190 DESCRIPTION . The Journal of Urban Economics provides a focal point for the publication of research papers in the rapidly expanding field of urban economics. It publishes papers of great scholarly merit on a wide range of topics and employing a wide range of approaches to urban economics. The Journal welcomes papers that are theoretical or empirical, positive or normative. Although the Journal is not intended to be multidisciplinary, papers by noneconomists are welcome if they are of interest to economists. Brief Notes are also published if they lie within the purview of the Journal and if they contain new information, comment on published work, or new theoretical suggestions. Benefits to authors We also provide many author benefits, such as free PDFs, a liberal copyright policy, special discounts on Elsevier publications and much more. Please click here for more information on our author services. Please see our Guide for Authors for information on article submission. If you require any further information or help, please visit our Support Center IMPACT FACTOR . 2020: 3.637 © Clarivate Analytics Journal Citation Reports 2021 ABSTRACTING AND INDEXING . RePEc ABI/Inform Asian Pacific Economic Literature Journal of Economic Literature Gale Group Trade & Industry Database Social SciSearch Current Contents Embase PubMed/Medline Environmental Sciences DIALOG NewsRoom Journal of Economic Literature Web of Science AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK 24 Sep 2021 www.elsevier.com/locate/jue 1 EDITORIAL BOARD . -

Econ 414 Syllabus: Urban Economics

Econ 414: Urban Economics Syllabus – Please read carefully and consult regularly Economics 414: Urban Economics University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Fall 2016 Professor David Albouy Office: 216 David Kinley Hall (DKH) Office Hours: Tuesday 3:30-4:50 pm Email: [email protected] Lecture: Monday and Wednesday: 2:00-3:20pm, 113 David Kinley Hall Description: The economics of cities, especially in housing, labor, and transportation. Topics include rent and wage determination; the location decisions of households and firms, quality of life amenities, agglomeration economies, and optimal city size; economics and policy of housing, transportation, local government, land use, discrimination, segregation, and crime. Takes historical and contemporary views, applying theory and empirical methods. Prerequisites: Intermediate microeconomics (e.g., ECON 302). Statistics/econometrics useful. Grading 20% 1st Midterm exam (in class Sep 28) 20% 2nd Midterm exam (in class Nov 9) 30% Final exam (Dec 13, 8:00-11am, cumulative) Exams are based primarily on material taught in lecture. However, some questions may refer to material only explained fully in the required reading. 30% Six assignments (Sep 14, Sep 28, Oct 12, Oct 26, Nov 16, and Dec 7), each worth 5%: 5% Strong effort with mostly correct answers 4 Good effort with many correct answers 3 Mediocre effort with many wrong answers. 2 Sad effort/very incomplete, but at least the questions are written down. 1 A sheet with just your name on it and the assignment number (!) 0% Missing or late - please hand in whatever you have! **Up to 5% extra credit for attendance, class participation, and pronouncing my name correctly.