Aural Speed-Reading: Some Historical Bookmarks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Talking Books for the Blind and Physically Handicapped

cover cvr1 444n2_2p.indd4n2_2p.indd ccvr1vr1 33/2/2005/2/2005 44:11:08:11:08 PPMM Baker & Taylor 4c page cvr2 444n2_2p.indd4n2_2p.indd ccvr2vr2 33/2/2005/2/2005 44:11:47:11:47 PPMM /"-" Ê ÒÊ// -Ê, Ê7, Ê7 t Óää{Ê " Ê"ÕÌÃÌ>`}ÊV>`iVÊ/Ìi UÊÊ VÞV«i`>ÊvÊ iÌ VÃÊ>V>Ê,iviÀiViÊ1-Ò® UÊÊ VÞV«i`>ÊvÊ Õ`` ÃÊ>V>Ê,iviÀiViÊ1-Ò® UÊÊ VÞV«i`>ÊvÊ `ÀiÊ>`Ê ` `ÊÊÃÌÀÞÊ>`Ê-ViÌÞÊÊ >V>Ê,iviÀiViÊ1-Ò® UÊÊ VÞV«i`>ÊvÊ*«Õ>ÌÊ>V>Ê,iviÀiViÊ1-Ò® UÊÊ VÞV«i`>ÊvÊ,ÕÃÃ>ÊÃÌÀÞÊ>V>Ê,iviÀiViÊ1-Ò® UÊÊÊ VÞV«i`>ÊvÊÌ iÊÀi>ÌÊ i«ÀiÃÃÊ>V>Ê,iviÀiViÊ1-Ò® UÊÊÊ VÞV«i`>ÊvÊÌ iÊ`iÀÊ``iÊ >ÃÌÊEÊ ÀÌ ÊvÀV>ÊÊ >V>Ê,iviÀiViÊ1-Ò® UÊÊÀâi½ÃÊ>ÊviÊ VÞV«i`>Ê/ ÃÊ>iÒ® Óää{Ê ÃÌÊ `ÌÀÃ½Ê Vi UÊÊiÀV>Ê iV>`iÃÊ*À>ÀÞÊ-ÕÀViÃÊ/ ÃÊ>iÒ® UÊÊ VÞV«i`>ÊvÊiÃL>]Ê>Þ]Ê ÃiÝÕ>Ê>`Ê/À>Ã}i`iÀÊÃÌÀÞÊÊ ÊiÀV>Ê >ÀiÃÊ-VÀLiÀ½ÃÊ-ÃÁ® UÊÊ VÞV«i`>ÊvÊÌ iÊÀi>ÌÊ i«ÀiÃÃÊÊ >V>Ê,iviÀiViÊ1-Ò® UÊÊ ÕÀ«iÊ£{xäÊÌÊ£Çn\Ê VÞV«i`>ÊvÊÌ iÊ >ÀÞÊÊ `iÀÊ7À`Ê >ÀiÃÊ-VÀLiÀ½ÃÊ-ÃÁ® UÊÊ>ÀÊVÌÃÊvÊ }ÀiÃÃÊ>V>Ê,iviÀiViÊ1-Ò® UÊÊ VÞV«i`>ÊvÊ Ì }Ê>`Ê>Ã Ê >ÀiÃÊ-VÀLiÀ½ÃÊ-ÃÁ® £näänÇÇ ÜÜÜ°}>i°V ^ÊÓääxÊ/ ÃÊ>i]Ê>Ê«>ÀÌÊvÊ/ iÊ/ ÃÊ À«À>Ì°Ê/ Ã]Ê-Ì>ÀÊ}Ê>`Ê>V>Ê,iviÀiViÊ1-ÊÊ >ÀiÊÌÀ>`i>ÀÃÊ>`Ê>iÊ>`Ê >ÀiÃÊ-VÀLiÀ½ÃÊ-ÃÊ>ÀiÊÀi}ÃÌiÀi`ÊÌÀ>`i>ÀÃÊÕÃi`Ê iÀiÊÕ`iÀÊViÃi° 444n2_2p.indd4n2_2p.indd 5577 33/2/2005/2/2005 44:11:51:11:51 PPMM OCLC 4c page 58 444n2_2p.indd4n2_2p.indd 5588 33/2/2005/2/2005 44:11:55:11:55 PPMM Renée Vaillancourt McGrath Features Editor Kathleen M. -

American Printing House for the Blind Inc

THE FILSON CLUB HISTORY QUARTERLY VOL 36 LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY, JANUARY, 1962 NO. 1 AMERICAN PRINTING HOUSE FOR THE BLIND, INC. (1858 - 1961) A Century of Service to the Blind BY WILLIAM C. DABNEY, PRESIDENT Louisville, Kentucky A paper given before The Filson Club, April 3, 1961 I welcome the opportunity tonight to tell you something of the American Printing House for the Blind of Louisville, Kentucky, be- cause I have found that comparatively few residents of this com- munity know much about the work that this institution is carrying on. So that you may know the nature of the American Printing House for the Blind, I should like to tell you that it is the oldest national private agency for the blind in the United States, having been founded over 103 years ago on January 23, 1858, and is today the l•rgest publishing house and manufacturer of special devices for the aid of the blind in the world. It is unique in that, on the one hand, it is a seg- ment of industry, manufacturing products solely for the use of the blind, and employing the best and most efficient methods of industrial production, and, on the other, it carries on its business on a strictly non-profit basis. It also holds a singular position in the field of work for the blind in that, not only is it the textbook printery for the whole United States, but the materials that it produces are determined, not so much by the Printing House itself, as by the special needs of blind people and work in their behalf. -

A Voice E-Book Reading System Designed for the Visually Impaired People

A Voice E-book Reading System Designed for the Visually Impaired People Hsiao Ping Lee, Chung Shan Medical University, Taiwan Tzu-Fang Sheu, Providence University, Taiwan I-Wen Huang, Chung Shan Medical University, Taiwan The Asian Conference on Education & International Development 2020 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract No matter in life, study, or at work, reading is one of the major sources to obtain information. However, traditional books are mostly printed on paper. The books are not suitable for visually impaired persons to read. Though such a situation can be improved by Optical Character Recognition (OCR) technology. However, the quantity or timeliness of such resources exhibits a big gap versus that of normal sources of information for the general public. While E-books have become increasingly popular, due to the lack of consideration of the special needs of the visually impaired, as well as appropriate reading systems, the visually impaired still face many difficulties in E-book reading. In this project, we proposed a voice reading system for the visually impaired. The system provides an accessible E-book reading environment with content parsing and speech synthesis technologies. Additionally, an accessible E-book reader App is also developed with friendly interface designs for visually impaired persons. This system supports the common-used E-book format, offers a better, faster, and more convenient E-book reading environment for the visually impaired, and improves the situations of insufficient amount and poor timeliness. This improved E-book reading system for the visually impaired people would help the visually impaired people in E-learning and information access. -

Evaluating Audio Books As Supported Course Materials in Distance Education: the Experiences of the Blind Learners

The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology – TOJET October 2007 ISSN: 1303-6521 volume 6 Issue 4 Article 2 EVALUATING AUDIO BOOKS AS SUPPORTED COURSE MATERIALS IN DISTANCE EDUCATION: THE EXPERIENCES OF THE BLIND LEARNERS Prof. Dr. Aydin Ziya OZGUR Asst. Prof. Huseyin Selcuk KIRAY Anadolu University, Open Education Faculty [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT Anadolu University has a technical infrastructure, well-qualified faculty, and operates in an innovative and flexible frame. It takes an initiative role to meet the needs of higher education in Turkey by providing equal opportunity not only to satisfy those who value the principle of lifelong education but also seeks new information via distance education with the help of information and communication technologies. Anadolu University Open Education System utilizes all the facilities of contemporary education technology as well as traditional methods in its practices of distance education. Moreover, it provides the learners with the individualized, diversified and enriched services and the opportunities of contemporary education and communication technologies. The audio-book project is designed and based on individualized learning principles, notablly for the blind students, in the scope of Anadolu University Open Education System. This project enables the blind learners to study on their own, exempting them from the requirement of studying with someone else, and provides them with the opportunity to study any subjects in the book at their suitable convenience. There are approximately 300 blind students involved in this system. There are 14 course books tailored for the blind students needs whereas more than 21 books of the process of recording are still utilized. -

Annual Report, FY 2013

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE LIBRARIAN OF CONGRESS FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING SEPTEMBER 30, 2013 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE LIBRARIAN OF CONGRESS for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2013 Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2014 CONTENTS Letter from the Librarian of Congress ......................... 5 Organizational Reports ............................................... 47 Organization Chart ............................................... 48 Library of Congress Officers ........................................ 6 Congressional Research Service ............................ 50 Library of Congress Committees ................................. 7 U.S. Copyright Office ............................................ 52 Office of the Librarian .......................................... 54 Facts at a Glance ......................................................... 10 Law Library ........................................................... 56 Library Services .................................................... 58 Mission Statement. ...................................................... 11 Office of Strategic Initiatives ................................. 60 Serving the Congress................................................... 12 Office of Support Operations ............................... 62 Legislative Support ................................................ 13 Office of the Inspector General ............................ 63 Copyright Matters ................................................. 14 Copyright Royalty Board ..................................... -

Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

ILLINO S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. BULLETIN OF THE CENTER FOR HILDREN'S BOOKS FEBRUARY 1987 VOLUME 40 NUMBER 6 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO GRADUATE LIBRARY SCHOOL 4m~ EXPLANATION OF CODE SYMBOLS USED WITH ANNOTATIONS * Asterisks denote books of special distinction. R Recommended. Ad Additional book of acceptable quality for collections needing more material in the area. M Marginal book that is so slight in content or has so many weaknesses in style or format that it should be given careful consideration before purchase. NR Not recommended. SpC Subject matter or treatment will tend to limit the book to specialized collections. SpR A book that will have appeal for the unusual reader only. Recommended for the special few who will read it. Except for pre-school years, reading range is given for grade rather than for age of child. C.U. Curricular Use. D.V. Developmental Values. BULLETIN OF THE CENTER FOR CHILDREN'S BOOKS (ISSN 0008-9036) is published monthly except August by The University of Chicago Press for The University of Chicago, Graduate Library School. Betsy Hearne, Editor; Zena Sutherland, Associate Editor. An advisory commit- tee meets weekly to discuss books and reviews. The members are Carla Hayden, Isabel McCaul, Hazel Rochman, Robert Strang, and Roger Sutton. SUBSCRIPTION RATES: 1 year, $23.00; $15.00 per year for two or more subscriptions to the same address: $15.00, student rate; in countries other than the United States, add $3.00 per subscription for postage. -

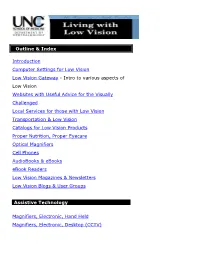

Intro to Various Aspects of Low Vision We

Outline & Index Introduction Computer Settings for Low Vision Low Vision Gateway - Intro to various aspects of Low Vision Websites with Useful Advice for the Visually Challenged Local Services for those with Low Vision Transportation & Low Vision Catalogs for Low Vision Products Proper Nutrition, Proper Eyecare Optical Magnifiers Cell Phones AudioBooks & eBooks eBook Readers Low Vision Magazines & Newsletters Low Vision Blogs & User Groups Assistive Technology Magnifiers, Electronic, Hand Held Magnifiers, Electronic, Desktop (CCTV) Magnifier Software for the Computer Screen Magnifiers for the Web Browser Low Vision Web Browsers Text to Speech Screen Readers, Software for Computers Scan to Speech Conversion Speech to Text Conversion, Speech Recognition The Macintosh The Apple Macintosh & its Special Strengths Mac Universal Access Commands Magnifiers for the Macintosh Text to Speech Screen Readers for Macintoshes Speech Recognition for Macs Financial Aid for Assistive Technology AudioBooks & eBooks Audiobooks are read to you by a recorded actor. eBooks allow you to download the book, magnify the type size and have the computer read to you out loud. Free Online eBooks • Online Books http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/ • Gutenberg Project http://www.gutenberg.net/index.php • Net Library – 24,000 eBooks & 2,000 eAudiobooks. Sign up thru your public library, then sign on to NC Live, and finally to Net Library. http://netlibrary.com/Centers/AudiobookCenter/Browse .aspx?Category=Lectures Free Online Audiobooks • http://librivox.org/newcatalog/search.php?title=&aut hor=&status=complete&action=Search • http://www.audiobooksforfree.com/ Books on CD & cassette North Carolina Library for the Blind (see above) http://statelibrary.dcr.state.nc.us/lbph/lbph.htm Downloadable Talking Books for the Blind https://www.nlstalkingbooks.org/dtb/ Audible.com. -

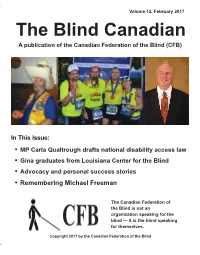

Blin Can Guts 8Th Final.Cdr

Volume 12, February 2017 The Blind Canadian A publication of the Canadian Federation of the Blind (CFB) In This Issue: l MP Carla Qualtrough drafts national disability access law l Gina graduates from Louisiana Center for the Blind l Advocacy and personal success stories l Remembering Michael Freeman TChe anadian F ederation of theB lind is not an organization speaking for the blind — it is the blind speaking for themselves. Copyright 2017 by the Canadian Federation of the Blind The Canadian Federation of the Blind is a non-profit, grassroots organization created by and for Blind Canadians. Its mandate is to improve the lives of blind people across the country through: blind people mentoring blind people; public education about the abilities of blind people; advocacy to create better opportunities and training for Blind Canadians. The long white cane is a symbol of empowerment and a tool for independence. With proper training, opportunity and a positive attitude, blindness is nothing more than a characteristic. Blind people can do almost everything sighted people can do; sometimes they just use alternative techniques to get the job done. We are educated. We have skills. We are independent. We are parents. We are teachers. We have wisdom. We represent the same range of human diversity, strengths and weaknesses as any other sector of the population. The CFB would like to realize a positive future for all people who are blind. A future where blind people can find employment; a future where blind people are valued for their contributions; a future where blind people are treated like anyone else. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 065 154 LI 003 775 TITLE Library Aids And

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 065 154 LI 003 775 TITLE Library Aids and Services Available to the Blind and Visually Handicapped. First Edition. INSTITUTION Delta Gamma Foundation, Columbus, Ohio. PUB DATE [72] NOTE 44p.; (0 References) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Adults; *Blind; Braille; Childrer.; Large Type Materials; Library Materials; *Library Services; *Partially Sighted; Senior Citizens; Talking Books; *Visually Handicapped ABSTRACT The information contained in this publication will be helpful in carrying out projects to aid blind and visually handicapped children and adults of all ages. Special materials available from the Library of Congress such as: talking books, books in braille, large print books, and books in moon tkpe are described. Other sources of reading materials for the blind ard partially sighted are listed, as are the magazines for the blind and partially sighted. Also included are cookbooks, and knitting and crocheting books for the blind and partially sighted. Sources of reading aids and supplies are listed and suggestions for giving personalized help to these handicapped persons are included. ()uthor/NH) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEH REPRO. DUCE() EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG. INATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN. IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF ECIU. CATION POSITION OR POUCY. LIBRARY AIDS AND SERVICES AVAILABLE TO THE BLIND AND VISUALLY HANDICAPPEDr This book was produced and printed in be Delta -

Handbook for Teachers of the Visually Handicapped. INSTITUTION American Printing House for the Blind, Louisville, Ky

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 043 991 EC 030 427 AUTHOR Napier, Grace D. ;Weishahn, Mel W. TITLE Handbook for Teachers of the Visually Handicapped. INSTITUTION American Printing House for the Blind, Louisville, Ky. SPONS AGENCY Bureau of Education for the Handicapped (DHEW/OE), Washington, D.C. BUREAU NO BR-272036 PUB DATE Sep 70 GRANT 0EG-2-6-062289-1E82(607) NOTE 117p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.50 HC-$5.95 DESCRIPTORS *Exceptional Child Education, Instructional Materials, Program Planning, *Teaching Guides, *Teaching Methods, *Visually Handicapped, Visually Handicapped Mobility, Visually Handicapped Orientation IDENTIFIERS Elementary and Secondary Education Act Title III ABSTRACT Designed to aid the inexperienced teacher of the visually handicapped, the handbook examines aspects of program objectives, content, philosophy, methods, eligibility, and placement procedures. The guide to material selection provides specific information on the acquisition of Braille materials, large type materials, recorded materials, direct reader service, and sources for educational aids. Suggestions for the regular classroom teacher of a blind student include the use of resource or itinerant teacher, methods to aid the blind child in his adjustment, and the maximum use of time and circumstances. Technigthts in the area of orientation and mobility are included with illustrations, and common visual impairments (such as glaucoma, nystagmus, and retrolental fibroplasia) are described. Sample forms and a bibliography concerning education of the visually handicapped are included. (RD) EC030427 HANDBOOK FOR TEACHERS of the VISUALLY HANDICAPPED LT 1PH LTLT LTLT - LT LTLTLTLTLT . .46 6... LT LTLTLT LT .6.. 64. LT LTLTLTLT LT LTLTLT LT 66 dm LT LTLTLT LT LT LTLTLTLT LT ,66.666 LTLTLTLT LTLTLT . -

International Meeting to Discuss Audio Technology As Applied to Library Services for Blind Individuals (3Rd, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, April 20-22, 1995)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 380 147 IR 055 503 TITLE International Meeting To Discuss Audio Technology as Applied to Library Services for Blind Individuals (3rd, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, April 20-22, 1995). Volumes 1-3. INSTITUTION Canedian National Inst. for the Blind, Vancouver (British Columbia).; Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. PUB DATE Apr 95 NOTE 425p.; Co-chaired by Euclid Herie and Kurt Frank Cylke. AVAILABLE FROMNational Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, 1291 Taylor Street, N.W., Washington, DC 20542. PUB TYPE Collected Works Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC17 Plus Pottage. DESCRIPTORS *Audio Equipment; Audiovisual Aids; *Blindness; Foreign Countries; Library Services; Nonprint Media; *Reading Materials; *Talking Books; Visual Impairments IDENTIFIERS Daisy Digital Talking Book System; *Digital Technology; Royal National Institute for the Blind (England) ABSTRACT This three-day conference on the subject of audio .technology for the production of materials for the blind, takes the court reporter approach to recording the speeches and discussions of the meeting. The result is a three volume set of complete transcripts, one volume for each day of the meeting, but continuous in form. The highlights of each day's discussion are as follows. Volume 1:(1) an introductory speech (by Euclid Herie) touching on the history of reading for the blind and of international meetings on the subject;(2) a representative from the Royal National Institute for the blind (RNIB, UK) outlines the major forces determining talking book formats;(3) John Cookson and Judith Dixon discuss the transition from analog to digital technology, from a U.S. -

Special Libraries, December 1962

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Special Libraries, 1962 Special Libraries, 1960s 12-1-1962 Special Libraries, December 1962 Special Libraries Association Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1962 Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarly Communication Commons Recommended Citation Special Libraries Association, "Special Libraries, December 1962" (1962). Special Libraries, 1962. 10. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1962/10 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Libraries, 1960s at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Libraries, 1962 by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPECIAL LIBRARIES ASSOCIATION Putting K~zotvled~rtr, TVo1.k OFFICERS DIRECTORS President SARAAULL ETHELS. KLAIIRE University of Houstun Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Cleveland, Ohio Houston 4, Texas First Vice-president and President-Elect JOANM. HUTCHINSON MRS. MILDREDH. BRODE Research Center, Diamorzd Alb.dt David Taylor Model Basin, Washington, D. C. Company, Painesville, Ohio Second Vice-president PAULW. RILEY ROBERTW. GIBSON,JR. College of Busi~zessAd711inistration Thomas J. Watson Research Center, Yorktou,n Boston College Heights, New York Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts Secretary MRS. JEANNEB. NORTH hhS. EI.IZABLTIIB. ROTH Lockheed Missiles d Space Company, Palo Standard Oil Company of Califor- Alto, California uia, San Francisco, California Treasurer EDWARDG. STRABLE R.4LpH H. PHELPS J. Waher Thompson Cotupan) Engineering Societies Library, New York, New YorR Chicago, Illinois Immediate Past-President LMRS.ELIZABETH R. USHER EUGENEB. JACKSON Metropolifan Museum of Atr Resear.ch Laboratories, General motor^ Corporation New York, New York Warren, Alichigan EXECUTIVE SECRETARY: Br~r.ivl.