Country Sheet Cyprus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study of the Geomorphology of Cyprus

STUDY OF THE GEOMORPHOLOGY OF CYPRUS FINAL REPORT Unger and Kotshy (1865) – Geological Map of Cyprus PART 1/3 Main Report Metakron Consortium January 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1/3 1 Introduction 1.1 Present Investigation 1-1 1.2 Previous Investigations 1-1 1.3 Project Approach and Scope of Work 1-15 1.4 Methodology 1-16 2 Physiographic Setting 2.1 Regions and Provinces 2-1 2.2 Ammochostos Region (Am) 2-3 2.3 Karpasia Region (Ka) 2-3 2.4 Keryneia Region (Ky) 2-4 2.5 Mesaoria Region (Me) 2-4 2.6 Troodos Region (Tr) 2-5 2.7 Pafos Region (Pa) 2-5 2.8 Lemesos Region (Le) 2-6 2.9 Larnaca Region (La) 2-6 3 Geological Framework 3.1 Introduction 3-1 3.2 Terranes 3-2 3.3 Stratigraphy 3-2 4 Environmental Setting 4.1 Paleoclimate 4-1 4.2 Hydrology 4-11 4.3 Discharge 4-30 5 Geomorphic Processes and Landforms 5.1 Introduction 5-1 6 Quaternary Geological Map Units 6.1 Introduction 6-1 6.2 Anthropogenic Units 6-4 6.3 Marine Units 6-6 6.4 Eolian Units 6-10 6.5 Fluvial Units 6-11 6.6 Gravitational Units 6-14 6.7 Mixed Units 6-15 6.8 Paludal Units 6-16 6.9 Residual Units 6-18 7. Geochronology 7.1 Outcomes and Results 7-1 7.2 Sidereal Methods 7-3 7.3 Isotopic Methods 7-3 7.4 Radiogenic Methods – Luminescence Geochronology 7-17 7.5 Chemical and Biological Methods 7-88 7.6 Geomorphic Methods 7-88 7.7 Correlational Methods 7-95 8 Quaternary History 8-1 9 Geoarchaeology 9.1 Introduction 9-1 9.2 Survey of Major Archaeological Sites 9-6 9.3 Landscapes of Major Archaeological Sites 9-10 10 Geomorphosites: Recognition and Legal Framework for their Protection 10.1 -

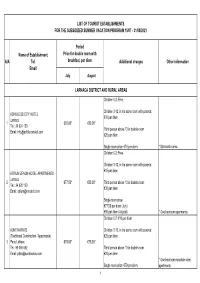

Larnaca District and Rural Areas List of Tourist Establishments for the Subsidized Summer Vacation Program 15/07

LIST OF TOURIST ESTABLISHMENTS FOR THE SUBSIDIZED SUMMER VACATION PROGRAM 15/07 - 31/08/2021 Period Name of Establishment Price for double room with Α/Α Tel. breakfast, per diem Additional charges Other information Email July August LARNACA DISTRICT AND RURAL AREAS Children 0-2: Free. Children 3-12, in the same room with parents: ACHILLEOS CITY HOTEL €10 per diem. Larnaca 1 €80,00* €80,00* Tel.: 24 624 150 Third person above 13 in double room: Email: [email protected] €20 per diem. Single room price: €70 per diem. * Standard rooms. Children 0-2: Free. Children 3-12, in the same room with parents: €15 per diem. ATRIUM ZENON HOTEL APARTMENTS Larnaca 2 €77,50* €80,00* Third person above 13 in double room: Tel.: 24 620 100 €30 per diem. Email: [email protected] Single room price: €77,50 per diem (July) €80 per diem (August). * One bedroom apartments. Children 0-2: €10 per diem. AUNT MARIA'S Children 3-12, in the same room with parents: (Traditional Construction / Apartments) €20 per diem. 3 Pano Lefkara €79,00* €79,00* Tel.: 99 356 652 Third person above 13 in double room: Email: [email protected] €20 per diem. * One bedroom mountain view Single room price: €79 per diem. apartments. 1 Period Name of Establishment Price for double room with Α/Α Tel. breakfast, per diem Additional charges Other information Email July August Children 0-2: Free. Children 3-12, in the same room with parents: BEST WESTERN PLUS LARCO HOTEL €20 per diem. Larnaca 4 €80,00 €80,00 Tel.: 24 657 100, 24 657 006 Third person above 13 in double room: Email: [email protected] €32 per diem. -

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

United Nations CCPR/C/CYP/5 International Covenant on Distr.: General 26 November 2020 Civil and Political Rights Original: English English, French and Spanish only Human Rights Committee Fifth periodic report submitted by Cyprus under article 40 of the Covenant pursuant to the optional reporting procedure, due in 2020*, ** [Date received: 27 July 2020] * The present document is being issued without formal editing. ** The annexes to the present report are on file with the secretariat and are available for consultation. They may also be accessed from the web page of the Human Rights Committee. GE.20-16001(E) CCPR/C/CYP/5 Contents Page List of abbreviations ...................................................................................................................... 3 I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 5 II. Provisions of the Covenant ........................................................................................................... 5 Α. General information on the national human rights situation, including new measures and developments relating to the implementation of the Covenant ............................... 5 Β. Specific information on the implementation of articles 1–27 of the Covenant, including with regard to the previous recommendations of the Committee .................................. 6 Constitutional and legal framework within which the Covenant is implemented (art. 2) ..... 6 Non-discrimination, -

Cyprus Authentic Route 2

Cyprus Authentic Route 2 Safety Driving in Cyprus Comfort Rural Accommodation Tips Useful Information Only DIGITAL Version A Village Life Larnaka • Livadia • Kellia • Troulloi • Avdellero • Athienou • Petrofani • Lympia • Ancient Idalion • Alampra • Mosfiloti • Kornos • Pyrga • Stavrovouni • Kofinou • Psematismenos • Maroni • Agios Theodoros • Alaminos • Mazotos • Kiti • Hala Sultan Tekke • Larnaka Route 2 Larnaka – Livadia – Kellia – Troulloi – Avdellero – Athienou – Petrofani – Lympia - Ancient Idalion – Alampra – Mosfiloti – Kornos – Pyrga – Stavrovouni – Kofinou – Psematismenos – Maroni – Agios Theodoros – Alaminos – Mazotos – Kiti – Hala Sultan Tekke – Larnaka Margo Agios Arsos Pyrogi Spyridon Agios Tremetousia Tseri Golgoi Sozomenos Melouseia Athienou Potamia Pergamos Petrofani Troulloi Margi Nisou Dali Pera Louroukina Avdellero Pyla Chorio Idalion Kotsiatis Lympia Alampra Agia Voroklini Varvara Agios Kellia Antonios Kochi Mathiatis Sia Aradippou Mosfiloti Agia Livadia Psevdas Anna Ε4 Kalo Chorio Port Kition Kornos Chapelle Delikipos Pyrga Royal LARNAKA Marina Salt LARNAKA BAY Lake Hala Sultan Stavrovouni Klavdia Tekkesi Dromolaxia- Dipotamos Meneou Larnaka Dam Kiti Dam International Alethriko Airport Tersefanou Anglisides Panagia Kivisili Menogeia Kiti Aggeloktisti Perivolia Aplanta Softades Skarinou Kofinou Anafotida Choirokoitia Alaminos Mazotos Cape Kiti Choirokoitia Agios Theodoros Tochni Psematismenos Maroni scale 1:300,000 0 1 2 4 6 8 10 Kilometers Zygi AMMOCHOSTOS Prepared by Lands and Surveys Department, Ministry of Interior, -

N Cyprus There Are Few If Any Private Gardens That Are Open to the Public, but Most Major Towns Have Municipal Gardens, Which Vary Greatly from Place I to Place

n Cyprus there are few if any private gardens that are open to the public, but most major towns have municipal gardens, which vary greatly from place I to place. Until very recently Cypriot gardens were mainly courtyards with a few herbs in pots and perhaps a grapevine or fig tree for shade during the long hot summer months. Latterly, with more and more Cypriots returning to their homeland from years spent in other countries where gardening is part of the culture, more adventurous plantings have been taking place and landscape gardeners are coming into their own, as people realise how therapeutic a garden can be after the rigours of work. In the valley where I live, amongst the courtyards and tiny planted strips around the houses, there are several gardens of note. In the village of Agia Anna in Larnaca District, there is a wonderful Cacti and Succulent Garden planted out on a rocky hillside. In the next village Psevdas, a garden lover has pruned the trees in his front garden into the most interesting shapes. In the same village two gardens on the main street have been landscaped in a modern style containing very old olive trees, which are such a part of the Cypriot landscape. My own garden in Mosfiloti has a lavender par terre, which has matured over the years. It no longer needs watering other than the rain which falls during the winter months, as the grey leaves protect the plants from the fierce-some sun. Many gardens are hidden away behind courtyard doors. If you are able to peek behind them, you will find some real jewels. -

Where to … Larnaka

WHERE TO … LARNAKA –Past & Present treasures revealed– WHERE TO… WHERE TO… 2 LARNAKA LARNAKA 3 Past & Present treasures revealed content welcome Past & Present treasures revealed WHERE to… WHERE to… STAY VISIT CTO Licensed Religious Sites Accommodation Establishments Cultural Sites Rural Larnaka 06 11 WHERE to… WHERE to… the chairman of the larnaka tourism Born and raised in Larnaka, he is pas- hope that you will begin to understand Board welcomes you to larnaka. sionate about his home, “I love every why this is the feeling that so many single thing about Larnaka. I strongly people from Larnaka carry in their GO TaSTE Dinos Lefkaritis, endeavours along believe that Larnaka is the most beau- hearts. with the other board members to tiful city in Cyprus.” highlight this beautiful, historical re- The charismatic personalities, the hos- Beaches . Watersports Dining gion. As you browse through our guide, we pitable warmth, as with good food is Leisure . Diving & Cruising Drinking Cycling . Nature Trails Events Diary 52 76 WHERE to… WHERE to… SHOP FIND Retail Therapy Tourist Information Maps 84 88 Published by Where To Cyprus for the Larnaka Tourism Board. Where To Cyprus endeavor to make every effort to ensure that the contents of this publica- tion are accurate at the time of publication. The editorial materials and views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of Where To Cyprus, its publish- ers or partners. Where To Cyprus Reserve All Rights to this publication and its content and it may not be reproduced in full or in part without expressed written permission of Where To Cyprus. -

The Population of the Mixed Villages of Cyprus Based on the 1960 Census

THE POPULATION OF THE MIXED VILLAGES OF CYPRUS BASED ON THE 1960 CENSUS Notes: (1) The villages with the * sign are in the north. (2) The names in parenthesis are those currently in use in the north. (3) This is just a quick list of these villages, it may be incomplete. (4) This font is used to indicate later additions to the list. NICOSIA DISTRICT Additional note: (Goodwin + Census) Nicosia [suburbs included] 73381GC 22134TC. [51% living in the suburbs] Nicosia within city limits 49% 25651GC, 14868TC Town/village G/C T/C G/C contact T/C contact Strovolos 7390 76 Aglantzia/Athalassa 3593 316 Kaimakli (Kucuk 8175 5130 Kaimakli)/Omorphita* (Kucuk Omorphita) Trahonas* 2316 921 Ayios Vasilios* (Turkeli) 492 117 Ayios Georgios Lefkas* 312 143 Akaki 1355 156 Ambelikou* (Baglikoy) 63 485 Arethiou 265 90 Dhali 2403 206 Dhenia 196 128 Flasou 427 97 Kalon Horion Lefkas* 244 307 (Camlikoy) Karavostasi*/Xeros* 1111 333 (Gemikonagi) Kato Deftera 464 37 Mathiatis 201 208 Morfou* (Guzelyurt) 6480 123 Neo Horio* (Minarelikoy) 1157 230 Orounta 601 39 Peristerona 690 476 Potamia 220 319 Pyroi* (Galizer) 374 86 Skylloura* (Yilmazkoy) 504 89 Palekithro* (Balikesir) 862 251 KYRENIA DISTRICT Town/village G/C T/C G/C contact T/C contact Kyrenia* 2802 696 Lapithos* (Lapta) 3124 370 Templos* (Zeytinlik) 61 161 Ayia Irini* (Akdeniz) 166 305 Ayios Georgios* (Karaoglanoglu) 618 203 Vasilia* (Karsiyaka) 855 213 Diorios* (Tebebasi) 514 156 Kazafani* (Ozankoy) 458 598 LIMASSOL DISTRICT Town/village G/C T/C G/C contact T/C contact Limassol 37478 6115 Kato Polemidia -

Press Release “The Religious Heritage of Cyprus” on Website

Press Release “The Religious Heritage of Cyprus” on Website 2 August 2021 The Office of the Religious Track of the Cyprus Peace Process under the Auspices of the Embassy of Sweden (RTCYPP) and Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) Cyprus announce the launch of “The Religious Heritage of Cyprus” website https://www.cyreligiousheritage.org/ The website contains an interactive map with Christian and Muslim places of worship and cemeteries, including photos and background information, starting with the districts of Larnaca and Kyrenia followed by the district of Nicosia, coming soon. Presented in a simple, descriptive, and impartial way, it allows everyone interested to witness the current status of the religious heritage of the island and learn more about it. From the very beginning of the RTCYPP, the Religious Leaders have advocated for the right to freedom of religion or belief and the protection of the shared religious heritage of Cyprus including free access to all sacred spaces to restore, renovate and worship. Since 2011, they have worked together to promote the universal values of religious freedom and invited others to join them. The website, launched today, is part of the Religious Heritage of Cyprus project begun in 2019 headed by Dr Thorsten Kruse from the University of Münster in Germany, endorsed by the Religious Leaders of Cyprus and supported by the Office of RTCYPP. The result was the first ever research publication where Christian and Muslim religious monuments and cemeteries appear side by side, called “The Religious Heritage of Cyprus - a Survey in the Districts of Kyrenia and Larnaca”, mapping out Christian monuments and sites in the Kyrenia district and Muslim monuments and sites in the Larnaca District; funded by the Human Rights Fund of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands and supported onsite by the Embassy of the Netherlands in Nicosia. -

Between Politics and Technopolitics

DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY AND HISTORY OF SCIENCE Division of History of Science and Technology Postgraduate Programme in History and Philosophy of Science and Technology PhD Thesis Between politics and technopolitics: critical episodes in energy and transportation infrastructures in colonial Cyprus Ανάμεσα στην πολιτική και τεχνοπολιτική: κρίσιμα επεισόδια στις υποδομές ενέργειας και μεταφορών στην αποικιακή Κύπρο Serkan Karas ΔT 008/02 Advisory Committee: Professor Kostas Gavroglu (supervisor) Lecturer Dr Stathis Arapostathis Associate Professor Aristotle Tympas Examining Committee: Professor Jean Christianidis, Assistant Professor Faidra Papanelopoulou, Professor Costas Dimitracopoulos, Professor Theodore Arabatzis, Members of Advisory Committee July 2014, Athens Contents-Περιεχο List of Abbreviations- Λίστα Ακρωνυμίων List of Tables – Λίστα Πινάκων List of Maps- Λίστα Χαρτών List of Photographs- Λίστα Εικόνων Acknowledgments- Ευχαριστίες Prologue- Πρόλογος 1 Chapter 1. Integrating techno-politics into politics: Theoretical frameworks Κεφάλαιο 1. Ενσωματώνοντας την τεχνοπολιτική στην πολιτική: θεωρητικά πλαίσια 5 Chapter 2. The Colonial period in the history of Cyprus Κεφάλαιο 2. Η Αποικιακή περίοδος στην ιστορία της Κύπρου 34 Chapter 3. The (non)-making of railway in Cyprus: railway lines towards the sea Κεφάλαιο 3. Η (μη) κατασκευή σιδηρόδρομου στην Κύπρο: σιδηροδρομικές γραμμές προς τη θάλασσα 76 Chapter 4. Negotiating/translating imperial policy, nationalism and vested interests into harbours: the making of Famagusta Harbour and Larnaca Harbour improvements Κεφάλαιο 4. Διαπραγματεύοντας/μεταφράζοντας την αυτοκρατορική πολιτική, τον εθνικισμό και τα συμφέροντα στα λιμάνια: η κατασκευή του λιμανιού της Αμμοχώστου και τα έργα στο λιμάνι της Λάρνακας 156 Chapter 5: ‘Electrifying’ Cyprus Κεφάλαιο 5. «Ηλεκτρίζοντας» την Κύπρο 218 i Chapter 6. Post-war colonial port development: Colonial Development and Welfare Act 1945 Κεφάλαιο 6. -

Camp Cyprus Environmental Economics Activity

CAMP CYPRUS ENVIRONMENTAL ECONOMICS ACTIVITY ENVIRONMENTAL ECONOMICS PILOT APPLICATION CASE STUDY SOUTHERN LARNACA COASTAL AREA Prepared by Glafkos Constantinides, PAP RAC Consultant Savvas Maliotis National Consultant December 2007 CAMP Cyprus – Environmental Economics Activity Environmental Economics Pilot Application Case Study, December 2007 Page 1 of 83 The PAP/RAC Consultant Mr Glafkos Constantinides and the National Specialist Mr Savvas Maliotis wish to acknowledge the support of the Environment Service of the Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Environment of the Republic of Cyprus to CAMP Cyprus Project in the capacity of National Implementing Authority. Particular thanks are expressed to the Planning Bureau of the Ministry of Finance which acted as lead agency for the Environmental Economics Activity, the Team Leaders and staff. Above all, thanks are extended to the EE Activity Team for their support and contributions. Ms Egli Pandelakis, Economic Director and Team Leader, Planning Bureau Ms Georgia Christofidou, Senior Economic Planning Officer, Co-Team Leader, Planning Bureau Ms Joanna Constantinides, CAMP Cyprus National Coordinator, Environment Service Mr Giannis Gregoriou, Team Member, Planning Bureau Ms Alexia Georgiadou, Team Member, Department of Town Planning and Housing Mr Varnavas Pashioulis, Team Member, Department of Lands & Surveys Ms Athena Metaxa, Team Member, Cyprus Tourism Organization Mr Spyros Stephanou, Team Member, Water Development Department Ms Panayiota Hadjigeorgiou, Team Member, Water Development Department Ms Stavrini Theodosiou, Coastal Unit, Public Works Department Ms Marilena Kythreotou, Team Member, Department of Statistical Services, Ministry of Finance Ms Christalla Costa, Team Member, Department of Agriculture Mr Christoforos Pandeli, Team Member, Secretary of Pervolia Local Authority Acknowledgement is also extended to the Priority Actions Programme (PAP/RAC) of UNEP’s Mediterranean Actions Programme for their diverse contributions to CAMP Cyprus under which this Activity is implemented. -

( Αλαμινός - Μενογεια - Αγγλισίδες - Αλεθρικό - Σταθμός Λάρνακας ) Τεχνικη Σχολη Λαρνακας Technical School Larnaka

- - 412 - - Άγιοι Ανάργυροι Α Agioi Anargyroi A Agia Anna Κόκκινες Kokkines ( Αλαμινός - Μενογεια - Αγγλισίδες - Αλεθρικό - Σταθμός Λάρνακας ) Τεχνικη Σχολη Λαρνακας Technical School Larnaka Σταδιο Αντ. Παπαδοπουλος Stadium Ant. Papadopoulos ( Alaminos - Menogeia - Aglisides - Alethriko - Larnaka Station ) Συν. Τσιακκιλερό Tsiakkilero Settl. Άγιοι Ανάργυροι Β Agioi Anargyroi B Omirou s a Mosfilon Ivykou d Hwy. Limasol - Larnaka Σταδιο Αμμοχωστος v yrou Kyprianou (Timagia) Sp e Lysis Stadium Ammochostos Avenue s s P Egkomis a Καλό Χωριό - s Συν. Αγ. Γεωργίου Assias ou os A a l llad Peristeriou g g ia E Ag. Georgios Settl. ia r E104 e AfaneiasA g u s i en Patron B1 T y ve A Kalo Chorio Av h Πυργά P n E323 e u E323 Avenue Ellados Τριφύλλια k e l A S a mm Ektoros Λιμανι Λαρνακας i u L s oc nt Trifyllia arn h ik o ako o Βεργίνα a r Larnaka Port s Pyrga s Λάρνακα y Tefkrou Anthia to Σταδιο Γ.Σ.Ζ C g u Vergina h y a Finish l A G.S.Z. Stadium Larnaka n o Kamaras rch o P ie um Zakynthou pisk Κόρνος opou Pa Ch isio Olympou ami u t Mpe s i Κεντρικός Σταθμός tra Kornos i Di m B1 Central Bus Station IA Γενικο Νοσοκομειο Kilkis General Hospital Πυροσβ. Σταθμος 1 Mystra Fire Station 1 Louki Akrita Αστυνομικος Σταθμος Police Station a Pandoras k Telamonos a Κ Σινεπλεξ Δροσιά n r K Cineplex Evripidou Drosia Μαρινα Λαρνακας a Ακρόπολη Συν. Καμάρες 2 Tinou L Larnaka Marina u Δημ. Βιβλιοθηκη Akropoli - Kamares 2 Settl. -

United Nations Security Council on the Cyprus Problem Adopted ,,N~Njmously on 20 July 1974

iffi-·~' · UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page 183 fJ M Date 15/06/2006 9:27:44AM " iJ Time ~ IIIII IIII II IIII II IIIII Ill II IIIII Ill IIIIIII Ill II IIIII Ill II Ill IIIII II Ill II Ill IIIIIII Ill II IIIII Ill II Ill II Ill IIIII S-0903-0010-11-00001 Expanded Number S-0903-0010-11-00001 Title Items-in-Cyprus - documents, resolutions, reports by the Secretary-General - reports by the Secretary-General Date Created 22/05/1974 Record Type Archival Item Container S-0903-0010: Peackeeping - Cyprus 1971-1981 Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit I I UNITED NATIONS SECURITY s/11568 COUNCIL 6 December 1974 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH REPORT BY THE SECRETARY-GENERAL ON THE UNITED NATIONS OPERA'I'ION IN CYPRUS (for the period 23 May to 5 December 1974) CONTENTS INTRODUCTION • . • • • . • 2 I. THE SITUATION IN CYPRUS FROM 23 ~,AY TO THE COUP D'ETAT ON 15 JULY . 2 II. OUTLINE OF EVENTS FROM THE COUP D'ETAT OF 15 JULY TO THE CEASE-FIRE OF 16 AUGUST 1974 . 2 III. SUMMARY OF UNFICYP OPERATIONS FROM THE COUP D'ETAT 15 .TTJLY TO THE CEASE-FIRE OF 16 AUGUST 1974 ..... 4 IV. UNFICYP OPERATIONS FROM THE CEASE-FIRE ON 16 AUGUST UNTIL 5 DECEMBER 197 4 . • . 6 A. Concept of oper&,tions . • • . • • . 6 B. Liaison and co-operation • • • • 6 c. Maintenance of the cease-fire • • • •.. 7 D. Violations of the cease-fire by shooting incidents f • 7 E. Violations of the cease-fire by movement; construction of defensive positions 7 F.