EVENT MARKETING PLANNING Course Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE BEST :BROADCAST BRIEFING in CANADA Thursday, July 6, 2006 Volume 14, Number 7 Page One of Three

THE BEST :BROADCAST BRIEFING IN CANADA Thursday, July 6, 2006 Volume 14, Number 7 Page One of Three DO NOT RETRANSMIT THIS ENERAL: The CRTC’s annual broadcast monitoring report shows PUBLICATION BEYOND YOUR Canadians are watching a bit more TV, listening to a bit less radio RECEPTION POINT Gand accessing the Internet in record numbers. The Commission also included data on handheld technologies, e.g. last year (2005), 59% Howard Christensen, Publisher of us used cellphones, 16% used an IPod or other MP3 player, 8% used a Broadcast Dialogue 18 Turtle Path webcam, 7% used a personal digital assistant (PDA) and 3% used a Lagoon City ON L0K 1B0 BlackBerry. Still limited are the numbers who access the Internet from their (705) 484-0752 [email protected] cellphones or wireless devices, or use them for services other than their www.broadcastdialogue.com main purpose. Of the people who own a cellphone, BlackBerry or PDA, 7% use it to get news or weather information, 4% cent use it to get sports scores, 3% use it to take pictures or make videos and 2% use it to watch TV. Canadians listened to radio an average 19.1 hours a week in 2005, down slightly from 19.5 the year before. They watched an average of 25.1 hours of TV each week, up from 24.7 in 2004. Seventy-four per-cent of Canadian homes had a computer, and 78% of Canadians accessed the Internet in 2005, up from 71% and 76% respectively the year before. Other points included in the CRTC’s seventh Broadcasting Policy Monitoring Report include: RADIO – 913 English-language stations out of 1,223 radio services – 275 are French-language and 35 are third- language. -

2012 Bell Astral Acquisition Presentation

AiitifAtlAcquisition of Astral Analyst Conference Call March 16, 2012 Safe harbour notice Certain statements made in this presentation including, but not limited to, statements relating to the proposed acquisition by BCE Inc. of all of the issued and outstanding shares of Astral Media Inc., certain strategic benefits and operational, competitive and cost efficiencies expected to result from the transaction, Bell Canada’s expected level of pro forma net leverage ratio and other statements that are not historical facts, are forward-looking statements. Several assumptions were made by BCE Inc. in preparing these forward-looking statements and there are r is ks t hat actua l resu lts w ill differ mater ia lly from t hose contemp late d by our forwar d-lkilooking statements. As a result, we cannot guarantee that any forward-looking statement will materialize and you are cautioned not to place undue reliance on these forward-looking statements. The completion of the above-mentioned proposed transaction is subject to customary closing conditions, termination rights and other risks and uncertainties including, without limitation, any required regulatory approvals, including approval by the CRTC, Competition Bureau and TSX. Accordingly, there can be no assurance that the proposed transaction will occur, or that it will occur on the terms and conditions contemplated in this presentation. The proposed transaction could be modified, restructured or terminated. There can also be no assurance that the strategic benefits and competitive, operational and cost efficiencies expected to result from the transaction will be fully realized. The expected return within policy range by year-end 2014 of Bell Canada’s pro forma net leverage ratio assumes the issuance of treasury shares under our employees’ savings and dividend reinvestment plans as well as ongoing significant free cash flow generation which is subject to BCE Inc.’s risk factors disclosed in its 2011 Annual MD&A dated March 8, 2012 (included in the BCE 2011 Annual Report). -

BCE 2020 Annual Information Form

IN TWENTY-TWENTY WE WERE AT THE OF CONNECTIONS WHEN IT MATTERED MOST. ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2020 MARCH 4, 2021 In this Annual Information Form, we, us, our, BCE and the company mean, as the context may require, either BCE Inc. or, collectively, BCE Inc., Bell Canada, their subsidiaries, joint arrangements and associates. Bell means, as the context may require, either Bell Canada or, collectively, Bell Canada, its subsidiaries, joint arrangements and associates. Each section of BCE’s 2018, 2019 and 2020 management’s discussion and analysis (BCE 2018 MD&A, BCE 2019 MD&A and BCE 2020 MD&A, respectively) and each section of BCE’s 2020 consolidated financial statements referred to in this Annual Information Form is incorporated by reference herein. No other document shall be considered to be incorporated by reference in this Annual Information Form. The BCE 2018 MD&A, BCE 2019 MD&A, BCE 2020 MD&A and BCE 2020 consolidated financial statements have been filed with the Canadian provincial securities regulatory authorities (available at sedar.com) and with the United States (U.S.) Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) as exhibits to BCE’s annual reports on Form 40-F (available at sec.gov). They are also available on BCE’s website at BCE.ca. Documents and other information contained in BCE’s website or in any other site referred to in BCE’s website or in this Annual Information Form are not part of this Annual Information Form and are not incorporated by reference herein. All dollar figures are in Canadian dollars, unless stated otherwise. -

BCE 2020 Annual Report

IN TWENTY-TWENTY WE WERE AT THE OF CONNECTIONS WHEN IT MATTERED MOST. ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Advancing how Canadians connect with each other and the world OUR FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE Stepping up in a year like no other As the Bell team kept Canada connected in a challenging 2020, we built marketplace momentum with world-class network, service and content innovations for our customers while delivering sustainable dividend growth for our shareholders. 2020 financial performance Revenue * (3.8%) Adjusted EBITDA (1) * (4.0%) Capital intensity 18.4% Adjusted EPS (1) $3.02 Free cash flow (1) * (10.4%) * Compared to 2019 6.1 % +307% Dividend yield Total shareholder in 2020 (2) return 2009–2020 (3) +5.1 % +140% Increase in dividend Increase in dividend per common share per common share for 2021 2009–2021 (1) Adjusted EBITDA, adjusted EPS and free cash floware non-GAAP financial measures and do not have any standardized meaning under International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). Therefore, they are unlikely to be comparable to similar measures presented by other issuers. For a full description of these measures, see section 10.2, Non-GAAP financial measures and key performance indicators (KPIs) on pp. 115 to 117 of the MD&A. (2) Annualized dividend per BCE common share divided by BCE’s share price at the end of the year. (3) The change in BCE’s common share price for a specified period plus BCE common share dividends reinvested, divided by BCE’s common share price at the beginning of the period. 2 | BCE INC. 2020 AnnuAL REPORT OUR PURPOSE Bell’s goal and Strategic Imperatives Our goal is to advance how Canadians connect with each other and the world, and the Bell team is executing a clear strategy that leverages our strengths and highlights the opportunities of the broadband economy for our company and all our stakeholders. -

THE HAROLD Greenberg FUND LE FONDS Harold Greenberg ANNUAL REPORT 2007

THE HAROLD GREENBERG FUND LE FONDS HAROLD GREENBERG ANNUAL REPORT 2007. 2008 MESSAGE FROM OUR PARTNER Unequalled in their potential impact on society, the audiovisual media are also the most costly of all forms of cultural expression. Indeed, producing a quality work demands enormous resources, from the original idea to delivery of the finished product. From scriptwriters to actors, technicians, musicians, directors and producers, hundreds of people pool their efforts to bring a work to life. Canadian films and television programs have become so accessible that it’s easy to forget how much effort goes into their creation. They make us laugh, teach us something, get us thinking, or all of these things at the same time. Often, a film or television program reflects not IAN GREENBERG only who we are, but also our reality and our aspirations as Canadians. President and CEO Astral Media Inc. Money itself has no ideas. But ideas, even the best ones, can perish for lack of money. Astral Media’s The Harold Greenberg Fund/Le Fonds Harold Greenberg (Fund/Fonds) exists so that good ideas can come to life. Since it was created, Fund/Fonds has devoted more than $60 million to support film and television projects by Canadian creators. Following the acquisition of the remaining 50% of MusiquePlus Inc., Astral Media has committed to even more money to financing Fund/Fonds, by incorporating the MaxFACT funding program. This year, Fund/Fonds supported the production of music videos by performers such as Alfa Rococo, Andrée Watters and Martin Léon, to name a few. In cinema, we are very proud to see films that Fund/Fonds has supported at one or more stages of their development get acclaim. -

BCE 2018 Annual Information Form

Today / Fibre to the home / Rural Internet / Customer service / Wireless networks / Crave / Collaboration solutions / Smart Cities / IoT / Streaming video / Whole Home Wi-Fi / Fibe TV / Basketball / Inclusion / Virtual networks / Advertising reach / Mobile roaming / Hockey / Alt TV / Football / Connected cars / R&D / Local programming / Managed services / Streaming radio / Mental health / Manitoba / Prepaid wireless / Enterprise security / Business efficiency / Public safety / Self serve / News, sports & entertainment / The Source / Montréal transit / Branch connectivity / Order tracking / Content production / Soccer / Broadband speeds / Unified communications / Data centres / Cloud computing / Smart Homes / Canada / Dividends / just got better. Annual Information Form for the year ended December 31, 2018 MARCH 7, 2019 In this Annual Information Form, we, us, our and BCE mean, as the context may require, either BCE Inc. or, collectively, BCE Inc., Bell Canada, their subsidiaries, joint arrangements and associates. Bell means, as the context may require, either Bell Canada or, collectively, Bell Canada, its subsidiaries, joint arrangements and associates. MTS means, as the context may require, until March 17, 2017, either Manitoba Telecom Services Inc. or, collectively, Manitoba Telecom Services Inc. and its subsidiaries; and Bell MTS means, from March 17, 2017, the combined operations of MTS and Bell Canada in Manitoba. Each section of BCE’s 2016, 2017 and 2018 management’s discussion and analysis (BCE 2016 MD&A, BCE 2017 MD&A and BCE 2018 MD&A, respectively) and each section of BCE’s 2018 consolidated financial statements referred to in this Annual Information Form is incorporated by reference herein. The BCE 2016 MD&A, BCE 2017 MD&A, BCE 2018 MD&A and BCE 2018 consolidated financial statements have been filed with the Canadian provincial securities regulatory authorities (available at sedar.com) and with the United States (U.S.) Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) as exhibits to BCE’s annual reports on Form 40-F (available at sec.gov). -

Download Files to the Captured and Preventive Measures That Need Risk

VOLUME 13 ISSUE 94 YEAR 2019 ISSN 1306 5998 S-400 TRIUMPH AIR & MISSILE DEFENCE SYSTEM AND TURKEY’S AIR & MISSILE DEFENCE CAPABILITY NAVANTIA - AMBITIOUS PROJECTS WHERE EXPERIENCE MATTERS A LOOK AT THE TURKISH LAND PLATFORMS SECTOR AND ITS NATO STANDARD INDIGENOUS SOLUTIONS BEHIND THE CROSSHAIRS: ARMORING UP WITH REMOTE WEAPON SYSTEMS AS THE NEW GAME CHANGERS OF TODAY’S BATTLEFIELD SEEN AND HEARD AT THE INTERNATIONAL PARIS AIR SHOW 2019 ISSUE 94/2019 1 DEFENCE TURKEY VOLUME: 13 ISSUE: 94 YEAR: 2019 ISSN 1306 5998 Publisher Hatice Ayşe EVERS 6 Publisher & Editor in Chief Ayşe EVERS [email protected] Managing Editor Cem AKALIN [email protected] Editor İbrahim SÜNNETÇİ [email protected] Administrative Coordinator Yeşim BİLGİNOĞLU YÖRÜK [email protected] International Relations Director Şebnem AKALIN [email protected] 20 Correspondent Saffet UYANIK [email protected] Translation Tanyel AKMAN [email protected] Editing Mona Melleberg YÜKSELTÜRK Robert EVERS Graphics & Design Gülsemin BOLAT Görkem ELMAS [email protected] Photographer Sinan Niyazi KUTSAL 28 Advisory Board (R) Major General Fahir ALTAN (R) Navy Captain Zafer BETONER Prof Dr. Nafiz ALEMDAROĞLU Cem KOÇ Asst. Prof. Dr. Altan ÖZKİL Kaya YAZGAN Ali KALIPÇI Zeynep KAREL DEFENCE TURKEY Administrative Office DT Medya LTD.STI Güneypark Kümeevleri (Sinpaş Altınoran) Kule 3 No:142 Çankaya Ankara / Turkey Tel: +90 (312) 447 1320 [email protected] www.defenceturkey.com 56 Printing Demir Ofis Kırtasiye Perpa Ticaret Merkezi B Blok Kat:8 No:936 Şişli / İstanbul Tel: +90 212 222 26 36 [email protected] www.demirofiskirtasiye.com Basım Tarihi Ağustos 2019 Yayın Türü Süreli DT Medya LTD. -

2012 Bell Astral Acquisition Press Release

For Immediate Release Bell to acquire Québec’s leading media company Astral • $3.38-billion transaction establishes Bell as the leader in French-language media • Astral’s broad national media portfolio includes top-tier TV, radio, digital and out-of-home properties • Supports Bell strategy to deliver the best content across every broadband screen in Québec • Astral President & CEO Ian Greenberg to join the BCE Board of Directors at closing MONTRÉAL, March 16, 2012 – BCE Inc. (Bell) today announced that it has signed a definitive agreement to acquire all of the issued and outstanding shares of Montréal-based Astral Media Inc. (Astral) and its leading specialty and pay television channels, radio stations, digital media properties and out-of-home advertising platforms in Québec and across the rest of Canada. Greatly strengthening Bell’s competitive position in the important Québec media marketplace, this transaction directly supports Bell’s strategy of investment and innovation in broadband networks and content. Bell will acquire all Class A Non-Voting Shares of Astral for $50 per share, representing a premium of 39% based on Astral’s volume-weighted average closing share price on the TSX for the last five trading days, for a total consideration of approximately $2.8 billion. Bell will also acquire all Class B Subordinate Voting Shares for $54.83 per share, for a total consideration of approximately $151 million, and all Special Shares for a total consideration of $50 million. The transaction is valued at approximately $3.38 billion, including net debt of $380 million, and will be funded with a combination of cash (approximately 75% of the equity purchase price) and BCE common equity (approximately 25% or $750 million), with Bell retaining the right to replace shares with cash, in whole or in part, at closing. -

July 2011 Vol.12, No.7

Color Page BAYAY ROSSINGSROSSINGS “The VoiceB of the Waterfront” CC July 2011 Vol.12, No.7 A View to a Spill Gateway to the North Bay Cup Catamarans’ Bay Debut Vallejo Transit Center Opens Friendlier Shade of Green The Bay’s Forgotten Jewel Lawn Conversions Take Root Nature, History on Angel Island Complete Ferry Schedules for all SF Lines Color Page Mention this ad and receive a 2 for 1 Just a Ferry Ride Away… Reserve Tasting WINERY & TASTING ROOM 2900 Main Street, Alameda, CA 94501 Right Next to the Alameda Ferry Terminal www.RosenblumCellars.com Open Daily 11–6 • 510-995-4100 ENJOY OUR WINES RESPONSIBLY © 2009 Rosenblum Cellars, Alameda, Ca ������������������� �� Excellent Financing is Available ���������� ���������������������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������ �������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������������������� Bel_BayCrossing3.15.indd 1 3/15/11 6:10 PM columns features 10 BAYKEEPER 14 AMERICA’S CUP Safest Protection Offered AC45 Catamarans by Mineral Sunscreens Exercise License to Spill 22 by Deb Self in Thrilling Bay Debut by BC Staff guides 11 IT CAME FROM BENEATH THE SEA 16 GREEN PAGES 20 WATERFRONT ACTIVITIES The Sevengill Shark Is Homeowners Reap Green -

Le Fonds Harold Greenberg, 10 Years of Action!

20 YEARS OF ACTION! ANNUAL REPORT 2005-2006 LE FONDS HAROLD GREENBERG, 10 YEARS OF ACTION! WE WERE THE FIRST BROADCASTER TO SET UP A PRIVATE FUND FOR FILM FINANCING THE HAROLD GREENBERG FUND 20 YEARS OF ACTION! INVESTMENTS TO DATE IN SUPPORT WE REMAIN COMMITTED TO CONTINUING OF CANADIAN WRITERS, DIRECTORS, PRODUCERS AND PERFORMERS TOTAL $50.7 MILLION OUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT FOR CANADIAN FILM AND TELEVISION PRODUCTIONS MESSAGE FROM OUR PARTNER One of the most important objectives of The Fund/Le Fonds when This is a special year for Astral Media The Harold Greenberg Fund/ Since 1986, The Fund/Le Fonds has continued to grow and to diver- it was founded was to assure that the elements necessary to Le Fonds Harold Greenberg. It marks the 20th anniversary of sify. Investments to date in support of Canadian writers, directors, make a successful industry could be found right here in Canada. support for the Canadian film and television industries for its producers and performers total $50.7 million, and this year alone As a funding partner, we are very proud of our long history of English-language Program and ten years of operation for its $5.1 million has been invested in 168 projects. The Fund/Le Fonds support for the industry and we feel strongly that the growth and French-language Program. Astral Media has always been unique in has programs in both official languages, supporting a wide array success of this industry will continue to depend on the essential its approach to the industry. Not only were we the first broadcaster of film and television productions including: feature films, mix of private and public funding. -

Szakdolgozat

SZAKDOLGOZAT Deák Tamás 2016 NEMZETI KÖZSZOLGÁLATI EGYETEM HADTUDOMÁNYI ÉS HONVÉDTISZTKÉPZŐ KAR KATONAI REPÜLŐ INTÉZET FEDÉLZETI RENDSZEREK TANSZÉK A V-1 ÉS V-2 MEGTORLÓFEGYVEREK ÉS EZEK HATÁSAI A KÉSŐBBI HADIIPARI FEJLESZTÉSEKRE A konzulens neve, beosztása: Dr. Szilvássy László alezredes, egyetemi docens Szakfelelős neve, beosztása: Dr. Békési Bertold alezredes, egyetemi docens Készítette: Deák Tamás honvéd tisztjelölt Szolnok 2016 Szakdolgozat-feladatlap Jóváhagyom! Szolnok,2015. október 28. Dr. Szilvássy László alezredes mb. tanszékvezető H_AN4_SHBRM75 tanulócsoport Szakdolgozat feladatlap Deák Tamás részére A SZAKDOLGOZAT/DIPLOMAMUNKA CÍME: A V-1 és V-2 megtorlófegyverek és ezek hatásai a későbbi hadiipari fejlesztésekre KIDOLGOZANDÓ FŐ KÉRDÉSEK: Tanulmány, amely bemutatja a V-1 és V-2 német csodafegyverek működését és azok kihatásait a modern kor rakétafejlesztéseire A konzultáló tanár neve: dr. Szilvássy László alezredes Főbb időpontok: Adatgyűjtés, jegyzetek készítése: 2015.december 31-ig. Konzultációk: 2016. április 27-ig. Az elkészített szakdolgozat/diplomamunka konzulenshez való eljuttatása: 2016. április 28-ig. A konzultációkon történő részvétel igazolása: 2016. április 28-ig. A dolgozat köttetése: 2016. május 02-ig Szakdolgozat/diplomamunka leadása a tanszékre: 2016. május 02-ig. ZVB-i tagok részére történő eljuttatás: 2016. május 09-ig. A kidolgozott szakdolgozat/diplomamunka minősítési foka (nyílt, szolgálati használatos, titkos) aláhúzni! Szolnok, 2015. október 28. (Dr. Palik Mátyás alezredes) mb. intézet igazgató -

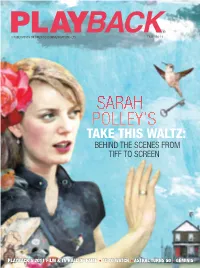

Take This Waltz: Behind the Scenes from Tiff to Screen

® A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. FALL 2011 TAKE THIS WALTZ: BEHIND THE SCENES FROM TIFF TO SCREEN PLAYBACK’S 2011 FILM & TV HALL OF FAME •• 10 TO WATCH ASTRAL TURNS 50 • GEMINIS PPB.Cover.Tiff.inddB.Cover.Tiff.indd 1 226/08/116/08/11 33:52:52 PPMM &21*5$78/$7,216 $675$/21<285WK$11,9(56$5< 7+$1.<28)25<285&217,18('68332572) 285%86,1(667+528*+2877+(<($56 :(/22.)25:$5'720$1<025( PPB.19704.eOne.Ad.inddB.19704.eOne.Ad.indd 1 225/08/115/08/11 22:24:24 PPMM TORONTO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2011 table of contents Director David Cronenberg on set during the fi lming of A Dangerous Method 9 Opening credits 31 Geminis 52 Special awards The Hot or Not list, #altgeminis and Allan Hawco and Adam Barken are Crafting nominations: The Kennedys Microsoft’s crazy new ad tech honoured for their standout and Stargate Universe crews talk Chanel accomplishments and George and alien workshops 12 TIFF 2011 Stroumboulopoulos gets the inaugural Show diaries: Producers, creators, humanitarian nod Film diary writers and directors share the stories Behind the scenes with Sarah Polley’s of how Republic of Doyle, Todd and the 56 10 to Watch Take This Waltz cast and crew Book of Pure Evil and Call Me Fitz came From all corners in the industry, a crop to life The evolution of indie marketing of fresh up-and-coming talent to keep From fi nger puppets to press an eye out for in the year ahead kits, Canadian fi lmmakers and 40 Hall of Fame distributors talk marketing indies Playback welcomes Pierre Juneau, 62 The Back Page Denis Héroux, Frédéric Back, Roger