Ad-Hoc Drought Management on an Overallocated River: the Ts Anislaus River, Water Years 2014-15 Philip Womble

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Year Evaluation of Predation in the Stanislaus River Project Information

Three Year Evaluation of Predation in the Stanislaus River Project Information 1. Proposal Title: Three Year Evaluation of Predation in the Stanislaus River 2. Proposal applicants: Steve Felte, Tri-Dam Project 3. Corresponding Contact Person: Jason Reed Tri-Dam Project P.O. Box 1158 Pinecrest, CA 95364 209 965-3996 [email protected] 4. Project Keywords: Anadromous salmonids At-risk species, fish Fish mortality/fish predation 5. Type of project: Research 6. Does the project involve land acquisition, either in fee or through a conservation easement? No 7. Topic Area: At-Risk Species Assessments 8. Type of applicant: Local Agency 9. Location - GIS coordinates: Latitude: 37.739 Longitude: -121.076 Datum: Describe project location using information such as water bodies, river miles, road intersections, landmarks, and size in acres. The proposed project will be conducted in the Stanislaus River between Knight’s Ferry at river mile 54.6 and the confluence with the San Joaquin River, in the mainstem San Joaquin River immediately downstream of the confluence, and in the deepwater ship channel near Stockton. 10. Location - Ecozone: 12.1 Vernalis to Merced River, 13.1 Stanislaus River, 1.2 East Delta, 11.2 Mokelumne River, 11.3 Calaveras River 11. Location - County: San Joaquin, Stanislaus 12. Location - City: Does your project fall within a city jurisdiction? No 13. Location - Tribal Lands: Does your project fall on or adjacent to tribal lands? No 14. Location - Congressional District: 18 15. Location: California State Senate District Number: 5, 12 California Assembly District Number: 25, 17 16. How many years of funding are you requesting? 3 17. -

Spring Gap-Stanislaus Project Is Located in Calaveras and Tuolumne Counties, CA on the Middle Fork Stanislaus River (Middle Fork) and South Fork Stanislaus River

Hydropower Project License Summary STANISLAUS RIVER, CALIFORNIA SPRING GAP-STANISLAUS HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT (P-2130) Photo Credit: California State Water Board This summary was produced by the Hydropower Reform Coalition Stanislaus River, CA STANISLAUS RIVER, CA SPRING GAP-STANISLAUS HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT (P-2130) DESCRIPTION: The Spring Gap-Stanislaus Project is located in Calaveras and Tuolumne Counties, CA on the Middle Fork Stanislaus River (Middle Fork) and South Fork Stanislaus River. Owned. The project, operated by Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E), has an installed capacity of 87.9 MW and occupies approximately 1,060 acres of federal land within the Stanislaus National Forest. Both the Middle and South Forks are popular destinations for a variety of outdoor recreation activities. With a section of the lower river designated by the State of CA as a Wild Trout Fishery, the Middle Fork is widely considered to be one of California’s best wild trout fisheries. The South Fork on the other hand, with its high gradient and steep rapids, is a popular whitewater kayaking and rafting destination. A. SUMMARY 1. License application filed: December 26, 2002 2. License Issued: April 24, 2009 3. License expiration: March 31, 2047 4. Capacity: Spring Gap- 6.0 MW Stanislaus- 81.9 MW 5. Waterway: Middle & North Forks of the Stanislaus River 6. Counties: Calaveras, Tuolumne 7. Licensee: Pacific Gas & Electric Company (PG&E) 8. Licensee Contact: Pacific Gas and Electric Company P.O. Box 997300 Sacramento, CA 95899-7300 9. Project area: The project is located in the Sierra Nevada mountain range of north- central California. -

Sacramento and San Joaquin Basins Climate Impact Assessment

Technical Appendix Sacramento and San Joaquin Basins Climate Impact Assessment U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation October 2014 Mission Statements The mission of the Department of the Interior is to protect and provide access to our Nation’s natural and cultural heritage and honor our trust responsibilities to Indian Tribes and our commitments to island communities. The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. Technical Appendix Sacramento and San Joaquin Basins Climate Impact Assessment Prepared for Reclamation by CH2M HILL under Contract No. R12PD80946 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Michael K. Tansey, PhD, Mid-Pacific Region Climate Change Coordinator Arlan Nickel, Mid-Pacific Region Basin Studies Coordinator By CH2M HILL Brian Van Lienden, PE, Water Resources Engineer Armin Munévar, PE, Water Resources Engineer Tapash Das, PhD, Water Resources Engineer U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation October 2014 This page left intentionally blank Table of Contents Table of Contents Page Abbreviations and Acronyms ....................................................................... xvii Preface ......................................................................................................... xxi 1.0 Technical Approach .............................................................................. 1 2.0 Socioeconomic-Climate Future -

2004 Vegetation Classification and Mapping of Peoria Wildlife Area

Vegetation classification and mapping of Peoria Wildlife Area, South of New Melones Lake, Tuolumne County, California By Julie M. Evens, Sau San, and Jeanne Taylor Of California Native Plant Society 2707 K Street, Suite 1 Sacramento, CA 95816 In Collaboration with John Menke Of Aerial Information Systems 112 First Street Redlands, CA 92373 November 2004 Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................................................... 1 Vegetation Classification Methods................................................................................................................ 1 Study Area ................................................................................................................................................. 1 Figure 1. Survey area including Peoria Wildlife Area and Table Mountain .................................................. 2 Sampling ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Figure 2. Locations of the field surveys. ....................................................................................................... 4 Existing Literature Review ......................................................................................................................... 5 Cluster Analyses for Vegetation Classification ......................................................................................... -

Gazetteer of Surface Waters of California

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTI8 SMITH, DIEECTOE WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 296 GAZETTEER OF SURFACE WATERS OF CALIFORNIA PART II. SAN JOAQUIN RIVER BASIN PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OP JOHN C. HOYT BY B. D. WOOD In cooperation with the State Water Commission and the Conservation Commission of the State of California WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1912 NOTE. A complete list of the gaging stations maintained in the San Joaquin River basin from 1888 to July 1, 1912, is presented on pages 100-102. 2 GAZETTEER OF SURFACE WATERS IN SAN JOAQUIN RIYER BASIN, CALIFORNIA. By B. D. WOOD. INTRODUCTION. This gazetteer is the second of a series of reports on the* surf ace waters of California prepared by the United States Geological Survey under cooperative agreement with the State of California as repre sented by the State Conservation Commission, George C. Pardee, chairman; Francis Cuttle; and J. P. Baumgartner, and by the State Water Commission, Hiram W. Johnson, governor; Charles D. Marx, chairman; S. C. Graham; Harold T. Powers; and W. F. McClure. Louis R. Glavis is secretary of both commissions. The reports are to be published as Water-Supply Papers 295 to 300 and will bear the fol lowing titles: 295. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part I, Sacramento River basin. 296. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part II, San Joaquin River basin. 297. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part III, Great Basin and Pacific coast streams. 298. Water resources of California, Part I, Stream measurements in the Sacramento River basin. -

Northern Calfornia Water Districts & Water Supply Sources

WHERE DOES OUR WATER COME FROM? Quincy Corning k F k N F , M R , r R e er th th a a Magalia e Fe F FEATHER RIVER NORTH FORK Shasta Lake STATE WATER PROJECT Chico Orland Paradise k F S , FEATHER RIVER MIDDLE FORK R r STATE WATER PROJECT e Sacramento River th a e F Tehama-Colusa Canal Durham Folsom Lake LAKE OROVILLE American River N Yuba R STATE WATER PROJECT San Joaquin R. Contra Costa Canal JACKSON MEADOW RES. New Melones Lake LAKE PILLSBURY Yuba Co. W.A. Marin M.W.D. Willows Old River Stanislaus R North Marin W.D. Oroville Sonoma Co. W.A. NEW BULLARDS BAR RES. Ukiah P.U. Yuba Co. W.A. Madera Canal Delta-Mendota Canal Millerton Lake Fort Bragg Palermo YUBA CO. W.A Kern River Yuba River San Luis Reservoir Jackson Meadows and Willits New Bullards Bar Reservoirs LAKE SPAULDING k Placer Co. W.A. F MIDDLE FORK YUBA RIVER TRUCKEE-DONNER P.U.D E Gridley Nevada I.D. , Nevada I.D. Groundwater Friant-Kern Canal R n ia ss u R Central Valley R ba Project Yu Nevada City LAKE MENDOCINO FEATHER RIVER BEAR RIVER Marin M.W.D. TEHAMA-COLUSA CANAL STATE WATER PROJECT YUBA RIVER Nevada I.D. Fk The Central Valley Project has been founded by the U.S. Bureau of North Marin W.D. CENTRAL VALLEY PROJECT , N Yuba Co. W.A. Grass Valley n R Reclamation in 1935 to manage the water of the Sacramento and Sonoma Co. W.A. ica mer Ukiah P.U. -

Water Quality Control Plan, Sacramento and San Joaquin River Basins

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Amendments to the 1994 Water Quality Control Plan for the Sacramento River and San Joaquin River Basins The Third Edition of the Basin Plan was adopted by the Central Valley Water Board on 9 December 1994, approved by the State Water Board on 16 February 1995 and approved by the Office of Administrative Law on 9 May 1995. The Fourth Edition of the Basin Plan was the 1998 reprint of the Third Edition incorporating amendments adopted and approved between 1994 and 1998. The Basin Plan is in a loose-leaf format to facilitate the addition of amendments. The Basin Plan can be kept up-to-date by inserting the pages that have been revised to include subsequent amendments. The date subsequent amendments are adopted by the Central Valley Water Board will appear at the bottom of the page. Otherwise, all pages will be dated 1 September 1998. Basin plan amendments adopted by the Regional Central Valley Water Board must be approved by the State Water Board and the Office of Administrative Law. If the amendment involves adopting or revising a standard which relates to surface waters it must also be approved by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) [40 CFR Section 131(c)]. -

Cvp Overview

Central Valley Project Overview Eric A. Stene Bureau of Reclamation Table Of Contents The Central Valley Project ......................................................2 About the Author .............................................................15 Bibliography ................................................................16 Archival and Manuscript Collections .......................................16 Government Documents .................................................16 Books ................................................................17 Articles...............................................................17 Interviews.............................................................17 Dissertations...........................................................17 Other ................................................................17 Index ......................................................................18 1 The Central Valley Project Throughout his political life, Thomas Jefferson contended the United States was an agriculturally based society. Agriculture may be king, but compared to the queen, Mother Nature, it is a weak monarch. Nature consistently proves to mankind who really controls the realm. The Central Valley of California is a magnificent example of this. The Sacramento River watershed receives two-thirds to three-quarters of northern California's precipitation though it only has one-third to one-quarter of the land. The San Joaquin River watershed occupies two- thirds to three-quarter of northern California's land, -

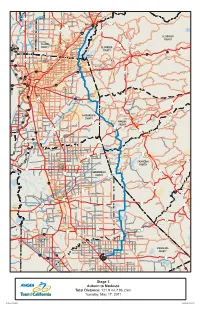

11 Atoc Stage 3

Rio Oso Rd Dry Creek Rd Big Ben Rd Rd Bell Garden Hwy Garden Locksley M Mount Pleasant Rd o Ln un North t V New erno n R Airport Rd Auburn Feather River d Atwood Rd Wally Allen Rd Allen Dowd Ave W Wise Rd Rd Mccourtney W Wise Rd Wise Rd Luther Rd Foresthill Rd 70 Crosby Herold Rd Herold Crosby Wise Rd Laurel Ave Nicolaus Ave Fruitvale Rd Fruitvale Rd Hungry Hollow Rd Gold Canal Rd Hill Rd Balderston Rd Virginiatown Rd El Dorado St Marcum Rd Nicolaus Rd Airport Rd 9th St Wentworth Springs Rd American River Trl 193 Fowler Rd El Centro Blvd Auburn Greenwood Rd O St Feather River Lincoln G St Lincoln Newcastle 1st St Ave East 193 Hwy Ln Ophir Rd Nelson Bear Creek Rd 193 Union Valley 99 Moore Rd Moore Rd Indian Hill Rd Reservoir Pleasant Grove Rd 65 49 Mosquito Rd English Colony Road Ridge Darling Taylor Rd Hackomiller Catlett Rd Catlett Rd Way 80 Garden Valley Rd Marshall Rd Rd W Catlett Rd Pacific Ave Athens Ave Whitney Blvd Garden Hwy Sunset Blvd Penryn Rd Dowd Ave Auburn Folsom Rd Howsley Rd Humphrey Rd King Rd EL DORADO Sierra College Blvd College Sierra Prospectors Rd Traverse Creek Rd Pleasant Grove Creek Canal Sunset BlvdRocklin Horseshoe Bar Rd COUNTY Sunset Blvd Industrial Ave Rattlesnake Bar Rd Phillip Rd Pacific StLoomis Fiddyment Rd Mount Murphy Rd Brewer Rd Blue Oaks Blvd Dick Cook Rd Coloma Rd Laird Rd Cross Canal 193 5th St Folsom Rock Creek Rd PLACER Wells Salmon Falls Rd Peavine Ridge Rd El Centro Blvd Rocklin Rd Lake 65 Whitney Blvd Ave 153 Sacramento River Roseville Foothills Blvd Pleasant Springview Dr Pleasant Grove Rd -

Basin Plan Amenment Implementing Control of Salt and Boron

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. AITACHMENT 2 AITACHMENT 1 RESOLUTION NO. RS-2004-0108 AMENDING THE WATER QUALITY CONTROL PLAN FOR THE SACRAMENTO RIVER AND SAN JOAQUIN RIVER BASINS FOR THE CONTROL OF SALT AND BORON DISCHARGES ~NTO THE LOWER SAN JOAQUIN RIVER Following are excerpts from Basin Plan Chapters I and IV shown similar to how they will appear after the proposed amendment is adopted. Deletions are indicated as strike through text (deleted te~) and additions are shown as underlined text (added text). Italicized text (Notation Text) is included to locate where the modifications will be made in the Basin Plan. All other text changes are shown accurately, however, formatting and pagination will change. 1 ATTACHMENT 1 RESOLUTION NO. R5-2004-0108 AMENDING THE WATER QUALITY CONTROL PLAN FOR THE SACRAMENTO RIVER AND SAN JOAQUIN RIVER BASINS FOR THE CONTROL OF SALT AND BORON DISCHARGES INTO THE LOWER SAN JOAQUIN RIVER Under the Chapter I heading: “Basin significant quantities of water to wells or springs, it can Description” on page IV-28, make the be defined as an aquifer (USGS, Water Supply Paper following changes: 1988, 1972). A ground water basin is defined as a hydrogeologic unit containing one large aquifer or several connected and interrelated aquifers (Todd, Groundwater Hydrology, 1980). -

Scanned Document

2 NOT FOR PUBLIC RELEASE BEFORE 12:00 o’clock noon EST on the day the President’s Budget is presented to Congress DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS – CIVIL WORKS FISCAL YEAR 2010 BUDGET REQUEST The Fiscal Year 2010 Budget provides $5,125,000,000 for the Civil Works program of the Army Corps of Engineers. The Civil Works program supports water resources development, management, and restoration through investigations and surveys, engineering and design, construction, and operation and maintenance, as authorized by Congress. Funding for the Civil Works program includes $464,000,000 in additional new resources, including $369,000,000 in non-Federal contributions. Based on current estimates, requested FY 2010 appropriations and additional new resources are as follows: Amount ($) Requested Appropriations: Investigations 100,000,000 Construction 1,718,000,000 1/ Operation and Maintenance 2,504,000,000 2/ Regulatory Program 190,000,000 Mississippi River and Tributaries 248,000,000 Expenses 184,000,000 Flood Control and Coastal Emergencies 41,000,000 Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program 134,000,000 Assistant Secretary of the Army, Civil Works 6,000,000 TOTAL APPROPRIATION REQUEST 5,125,000,000 Sources of Appropriations: General Fund (4,204,000,000) Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund (793,000,000) Inland Waterways Trust Fund (85,000,000) Special Recreation User Fees (43,000,000) TOTAL APPROPRIATION REQUEST (5,125,000,000) Additional New Resources: Rivers and Harbors Contributed Funds 369,000,000 3/ Coastal Wetlands Restoration Trust Fund 86,000,000 4/ Permanent Appropriations 9,000,000 TOTAL ADDITIONAL NEW RESOURCES 464,000,000 TOTAL PROGRAM FUNDING 5,589,000,000 1/ Includes $85,000,000 from the Inland Waterways Trust Fund. -

United States Department of the Interior

MP Region Public Affairs, 916-978-5100, http://www.usbr.gov/mp, May 2017 Mid-Pacific Region, New Melones Unit History acre-feet of water; today, New Melones Lake has a capacity of 2.4 million acre-feet. Located in the lower Sierra Nevada foothills The two irrigation districts that built the in Calaveras and Tuolumne County near original Melones Dam own and operate the Sonora, Calif., New Melones Dam and downstream Goodwin Diversion Dam, Reservoir are managed by the Bureau of which diverts Stanislaus River water into the Reclamation’s Mid-Pacific Region, Central district’s canal, and Tulloch Dam, Reservoir California Area Office. and Powerplant, located immediately downstream from New Melones Dam. Congress authorized the construction of Tulloch Reservoir provides Afterbay storage New Melones Dam in 1944 to prevent flood for reregulating power releases from New damage caused by rain and snowmelt to the Melones Powerplant under a contract lands and communities downstream on the between Reclamation and the two districts. Stanislaus River. Congress modified the The powerplant has a generating capacity of authorization in the 1962 Flood Control Act 322,596,000 kWh. to include irrigation, power, wildlife and fishery enhancement, recreation and water quality as other reasons for construction of the dam. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began construction of the dam in 1966, but public concerns over damage to cultural resources and the environment delayed completion until 1978. After the spillway and powerhouse were completed in 1979, the Corps transferred New Melones to New Melones Dam on the Stanislaus River Reclamation for integrated operation as the New Melones Unit of the East Side Recreation Division, Central Valley Project.