The Journal of Appellate Practice and Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2007 SC Playoff Summaries

PITTSBURGH PENGUINS STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 2 0 0 9 Craig Adams, Philippe Boucher, Matt Cooke, Sidney Crosby CAPTAIN, Pascal Dupuis, Mark Eaton, Ruslan Fedotenko, Marc-Andre Fleury, Mathieu Garon, Hal Gill, Eric Godard, Alex Goligoski, Sergei Gonchar, Bill Guerin, Tyler Kennedy, Chris Kunitz, Kris Letang, Evgeni Malkin, Brooks Orpik, Miroslav Satan, Rob Scuderi, Jordan Staal, Petr Sykora, Maxime Talbot, Mike Zigomanis Mario Lemieux CO-OWNER/CHAIRMAN Ray Shero GENERAL MANAGER, Dan Bylsma HEAD COACH © Steve Lansky 2010 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. All NHL logos and marks and NHL team logos and marks as well as all other proprietary materials depicted herein are the property of the NHL and the respective NHL teams and may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of NHL Enterprises, L.P. Copyright © 2010 National Hockey League. All Rights Reserved. 2009 EASTERN CONFERENCE QUARTER—FINAL 1 BOSTON BRUINS 116 v. 8 MONTRÉAL CANADIENS 93 GM PETER CHIARELLI, HC CLAUDE JULIEN v. GM/HC BOB GAINEY BRUINS SWEEP SERIES Thursday, April 16 1900 h et on CBC Saturday, April 18 2000 h et on CBC MONTREAL 2 @ BOSTON 4 MONTREAL 1 @ BOSTON 5 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD 1. BOSTON, Phil Kessel 1 (David Krejci, Chuck Kobasew) 13:11 1. BOSTON, Marc Savard 1 (Steve Montador, Phil Kessel) 9:59 PPG 2. BOSTON, David Krejci 1 (Michael Ryder, Milan Lucic) 14:41 2. BOSTON, Chuck Kobasew 1 (Mark Recchi, Patrice Bergeron) 15:12 3. -

Marcia Milgrom Dodge Curriculum Vita Overview

MARCIA MILGROM DODGE CURRICULUM VITA OVERVIEW • Freelance director and choreographer of classic and world premiere plays and musicals in Broadway, Off-Broadway, Regional, Summer Stock and University venues in the United States and abroad. More than 200 credits as director and/or choreographer. Also a published and produced playwright. • First woman Director/Choreographer hired by The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to direct and choreograph a major musical. • Adjunct Faculty and Guest Director at American Musical and Dramatic Academy. Also at New York University’s CAP 21, Marymount Manhattan College, Fordham University and University at Buffalo. Responsibilities include teaching undergraduate classes in acting, musical theatre and dance, since 1996 • Member of Stage Directors and Choreographers Society (SDC), since 1979. Fourteen (14) years of Executive Board service. • BA from the University of Michigan; includes membership in the Michigan Repertory Theatre and M.U.S.K.E.T. • Member of Musical Theatre Educators Alliance-International (MTEA), an organization of teachers in musical theatre programs from the United States, England and Europe, since 2009. • Resident Director, Born For Broadway, Annual Charity Cabaret, Founder/Producer: Sarah Galli, since 2009 • Advisory Board Member, The Musical Theatre Initiative/Wright State University, since 2013 • Associate Artist, Bay Street Theatre, Sag Harbor, NY, since 2008 • The Skylight Artists Advisory Board, Skylight Theatre, Los Angeles, since 2014 • Resident Director, Phoenix Theatre Company at SUNY Purchase, 1993-1995 • Associate Member of the Dramatists Guild, 2001-2015 • Member of Actors Equity Association, 1979-1988 EDUCATION & TRAINING BA in SPEECH COMMUNICATIONS & THEATRE, University Of Michigan, 1977 Dance Minor - Modern techniques include Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham, Horton, Luigi, Ethnic dance. -

Ice Hockey DIVISION I

72 DIVISION I Ice Hockey DIVISION I 2002 Championship Highlights Gophers Golden in Overtime: Perhaps it was a slight tweak in tradition that propelled Minnesota to the championship April 6 in St. Paul, Minnesota. Not since 1987 had a non-Minnesotan laced up the skates for the Gophers. The streak ended with Grant Potulny, a native of Grand Forks, North Dakota. Potulny scooped up a loose puck and beat Maine goaltender Matt Yeats, 16:58 into overtime, to bring the Gophers their first championship since 1979. When the puck hit the back of the net, the majority of the 19,324 on hand – a Frozen Four record – erupted. The three-session combined attendance at the Xcel Energy Center also set a Frozen Four record, totaling 57,957, to break the mark set at the 1998 championship in Boston’s Fleet Center (54,355). For the complete championship story go to the April 15, 2002 issue of The NCAA News at Photo by Vince Muzik/NCAA Photos www.ncaa.org on the World Wide Web. Minnesota players swarm Grant Potulny (18) after he scored in overtime, giving the Golden Gophers a 4-3 win over Maine in the championship game. Second period: C—Vesce (Stephen Baby, McRae), 7:56 New Hampshire 4, Cornell 3 Results (pp). Penalties: Q—Brian Herbert (slashing), 7:20; C— Cornell.............................................. 2 0 1—3 Greg Hornby (roughing), 10:18; Q—Craig Falite (rough- New Hampshire ................................ 3 0 1—4 EAST REGIONAL ing), 10:18; Q—Ben Blais (hitting from behind), 11:43; First period: NH—Jim Abbott (Preston Callander, Robbie Q—Blais (game misconduct), 11:43. -

2015 Playoff Guide Table of Contents

2015 PLAYOFF GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Company Directory ......................................................2 Brad Richardson. 60 Luca Sbisa ..............................................................62 PLAYOFF SCHEDULE ..................................................4 Daniel Sedin ............................................................ 64 MEDIA INFORMATION. 5 Henrik Sedin ............................................................ 66 Ryan Stanton ........................................................... 68 CANUCKS HOCKEY OPS EXECUTIVE Chris Tanev . 70 Trevor Linden, Jim Benning ................................................6 Linden Vey .............................................................72 Victor de Bonis, Laurence Gilman, Lorne Henning, Stan Smyl, Radim Vrbata ...........................................................74 John Weisbrod, TC Carling, Eric Crawford, Ron Delorme, Thomas Gradin . 7 Yannick Weber. 76 Jonathan Wall, Dan Cloutier, Ryan Johnson, Dr. Mike Wilkinson, Players in the System ....................................................78 Roger Takahashi, Eric Reneghan. 8 2014.15 Canucks Prospects Scoring ........................................ 84 COACHING STAFF Willie Desjardins .........................................................9 OPPONENTS Doug Lidster, Glen Gulutzan, Perry Pearn, Chicago Blackhawks ..................................................... 85 Roland Melanson, Ben Cooper, Glenn Carnegie. 10 St. Louis Blues .......................................................... 86 Anaheim Ducks -

2020-21 Big Ten Hockey Postseason Release - March 24, 2021

2020-21 BIG TEN HOCKEY POSTSEASON RELEASE - MARCH 24, 2021 Primary Contact: Megan Rowley, Assistant Director, Communications • Office: 847-696-1010 ext. 129 • E-mail: [email protected] • Twitter: @B1GHockey Secondary Contact: Leigh McGuirk, Bob Hammel Communications Intern • Office: 847-696-1010 ext. 142 • E-mail: [email protected] 2020-21 STANDINGS Conference Games All Games Win% Pts GP W L T OW-OL SW GF GA GP W L T Win% GF GA 1. Wisconsin^ .729 52 24 17 6 1 1-1 0 92 52 30 20 9 1 .683 115 74 2. Minnesota# .727 48 22 16 6 0 0-0 0 69 44 29 23 6 0 .793 110 58 3. Michigan .550 32 20 11 9 0 1-0 0 69 45 26 15 10 1 .596 91 51 4. Notre Dame .542 41 24 12 10 2 1-2 2 65 53 29 14 13 2 .517 84 78 5. Penn State .389 20 18 7 11 0 2-1 0 48 68 22 10 12 0 .455 65 81 6. Ohio State .273 20 22 6 16 0 0-2 0 39 82 27 7 19 1 .278 53 101 7. Michigan State .250 15 22 5 16 1 2-1 0 32 70 27 7 18 2 .296 40 77 ^ Big Ten Champion # Big Ten Tournament Champion Postseason Teams in Bold NCAA CHAMPIONSHIP SCHEDULE BIG TEN. BIG NEWS. FARGO REGIONAL • Four Big Ten teams were selected to participate in the 2021 NCAA Division I Men’s Ice Hockey Championship, with Scheels Arena, Fargo, N.D. -

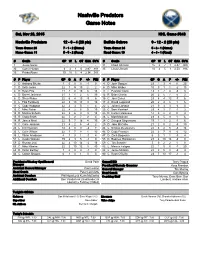

Nashville Predators Game Notes

Nashville Predators Game Notes Sat, Nov 28, 2015 NHL Game #348 Nashville Predators 12 - 6 - 4 (28 pts) Buffalo Sabres 9 - 12 - 2 (20 pts) Team Game: 23 7 - 1 - 2 (Home) Team Game: 24 5 - 8 - 1 (Home) Home Game: 11 5 - 5 - 2 (Road) Road Game: 10 4 - 4 - 1 (Road) # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% 1 Juuse Saros - - - - - - 31 Chad Johnson 15 5 7 1 2.47 .909 30 Carter Hutton 3 2 1 0 2.97 .911 35 Linus Ullmark 10 4 5 1 2.50 .916 35 Pekka Rinne 19 10 5 4 2.34 .911 # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM 2 D Anthony Bitetto 1 0 0 0 -1 0 4 D Josh Gorges 23 1 3 4 0 25 3 D Seth Jones 22 1 9 10 2 2 6 D Mike Weber 10 0 1 1 -2 13 4 D Ryan Ellis 21 2 8 10 5 14 9 L Evander Kane 13 2 2 4 -5 8 5 D Barret Jackman 21 1 1 2 5 39 12 R Brian Gionta 20 2 5 7 -5 2 6 D Shea Weber 22 6 4 10 -5 6 15 C Jack Eichel 23 8 4 12 -7 6 9 L Filip Forsberg 22 3 10 13 3 16 17 C David Legwand 20 2 4 6 1 6 11 C Cody Hodgson 22 2 3 5 1 4 22 L Johan Larsson 21 0 3 3 -3 0 12 C Mike Fisher 22 4 2 6 0 19 23 C Sam Reinhart 23 4 3 7 -1 2 14 D Mattias Ekholm 22 3 6 9 3 14 25 D Carlo Colaiacovo 14 0 2 2 0 4 15 R Craig Smith 22 5 2 7 2 4 26 L Matt Moulson 23 4 5 9 1 6 18 R James Neal 22 9 7 16 4 33 28 C Zemgus Girgensons 19 1 1 2 -1 6 19 C Calle Jarnkrok 21 4 2 6 -4 2 29 D Jake McCabe 21 2 0 2 -5 10 24 L Eric Nystrom 14 3 0 3 -3 7 44 L Nicolas Deslauriers 22 3 2 5 -4 14 33 L Colin Wilson 22 1 7 8 1 10 46 D Cody Franson 23 2 7 9 -3 12 38 L Viktor Arvidsson 4 1 0 1 -1 4 47 D Zach Bogosian 6 0 1 1 -3 4 51 L Austin Watson 19 2 3 5 -1 9 55 D Rasmus Ristolainen -

Orlando Ballet Hires Turnaround Expert Michael Kaiser

January 20, 2016 Orlando Ballet hires turnaround expert Michael Kaiser By MATTHEW J. PALM Dogged by financial struggles and a string of short-term executive directors, Orlando Ballet has hired a top name in arts leadership to shore up the organization. Michael M. Kaiser, who spent 15 years as president of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C., began consulting with the ballet this month. He left the center in August and “Giselle” dress rehearsal: Orlando Ballet dancers and Orlando Philharmonic is chairman of the DeVos musicians prepare for the ballet opening Friday, Oct. 30, at the Dr. Phillips Institute of Arts Center for the Performing Arts in Orlando. This will be the first season in Management at the which the ballet has live music for every performance. (Photo: Ricardo University of Maryland. Ramirez Buxeda) “Based on his track record of turning around arts organizations, and specifically ballet companies, we are confident his leadership will help us continue the momentum we have as a company and guide us toward long-term growth and success,” said Sibille Pritchard, a former Orlando Ballet board chair who is leading the turnaround effort. Facing a cash crunch before Christmas, the organization cut back on performances of “The Nutcracker” and threw the future of its much-ballyhooed live orchestral accompaniment into doubt. The ballet also severed ties with interim executive director James Cundiff, the group's sixth leader in six years. Throughout his career, Kaiser has demonstrated that he's not afraid of a challenge. During his tenure at the Kennedy Center, Kaiser oversaw a major renovation project and created the arts-management institute. -

Artsfund Winter 2010

WWW.ARTSFUND.ORG EMAIL: [email protected] VOLUME XVI, NO. 1, WINTER 2010 corporation could use the money—that organizations the flexibility to engage State of the Art my money can only go to developing in new directions and opportunities. He JAMES F. TUNE shaving cream, while mine can only go to notes an increase in conversations on PRESIDENT AND CEO toothpaste, especially if no one wanted the virtues of operating support, perhaps to pay to turn on the lights or pay the spurred at least in part by the struggles plumbing bill…[General operating many nonprofits are facing during these support] is fundamentally flexible times. working capital—money that can be used After our allocations process this past as opportunity arises…The organization summer, we decided it would be a good without access to such capital…misses idea to ask the arts organizations who the opportunity and quite possibly cannot applied for funding from ArtsFund what survive.” they think about our allocations process Funders around the country are and how it might be improved. Among the beginning to recognize that general questions asked was “Should ArtsFund operating support provided to nonprofits maintain the purpose of its grants as after careful evaluation of their business general operating support as opposed to operations has renewed importance. funding for specific programs?” Forty- In a recent article in the Wall Street four arts groups specifically responded; Journal, Palo Eisenberg, senior fellow The lead article in our Fall 2009 Newsletter of that number 43 responded vigorously at the Center for Public and Nonprofit “yes;” one responded “maybe both;” addressed the many program services ArtsFund Leadership at Georgetown University, none responded “no.” The 23 written provides to promote organizational excellence questioned whether current charitable comments repeated over and over among arts groups and to support the cause giving meets the needs of nonprofit how difficult it is to obtain operating of the arts in the public arena. -

Rhode Island Bar Journal Rhode Island Bar Association Volume 67

Rhode Island Bar Journal Rhode Island Bar Association Volume 67. Number 6. May/June 2019 Finding the Right Level: Viewing the Providence Water Supply from Historical and National Perspectives Navigating Title IX and Campus Sexual Misconduct Defense – Advocacy’s Wild West Your Moral Imperative to Routinely Practice Self-Care Book Review: Life is Short – Wear Your Party Pants by Loretta LaRoche Movie Review: On the Basis of Sex Articles 5 Finding the Right Level: Viewing the Providence Water Supply from Historical and National Perspectives Editor In Chief, Mark B. Morse, Esq. Samuel D. Zurier, Esq. Editor, Kathleen M. Bridge Editorial Board Victoria M. Almeida, Esq. 11 Navigating Title IX and Campus Sexual Misconduct Defense – Jerry Cohen, Esq. Advocacy’s Wild West Kayla E. Coogan O’Rourke, Esq. Eric D. Correira, Esq. John R. Grasso, Esq. James D. Cullen, Esq. William J. Delaney, Esq. 17 Your Moral Imperative to Routinely Practice Self-Care Thomas M. Dickinson, Esq. Nicole P. Dyszlewski, Esq. Katherine Itacy, Esq. Matthew Louis Fabisch, Esq. Keith D. Hoffmann, Esq. Meghan L. Hopkins, Esq. 23 Snake Eyes – American Bar Association Delegate Report – Matthew J. Landry, Esq. Midyear Meeting 2019 Christopher J. Menihan, Esq. Robert D. Oster, Esq. Lenore Marie Montanaro, Esq. Daniel J. Procaccini, Esq. Matthew David Provencher, Esq. Steven M. Richard, Esq. 25 The Ada Sawyer Award: The Rhode Island Women’s Bar Association’s Joshua G. Simon, Esq. Recognition of Women Lawyers Angelo R. Simone, Esq. Kelly I. McGee, Esq. Stephen A. Smith, Esq. Hon. Brian P. Stern Elizabeth Stone Esq. 2 7 BOOK REVIEW Life is Short – Wear Your Party Pants by Loretta LaRoche Dana N. -

Case: 20-2754 Document: 39-2 Page: 1 Date Filed: 02/15/2021

Case: 20-2754 Document: 39-2 Page: 1 Date Filed: 02/15/2021 Nos. 20-2754, 20-2755 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT COUNTY OF OCEAN, et al., Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. GURBIR S. GREWAL, in his official capacity as Attorney General of the State of New Jersey, et al., Defendants-Appellees. ROBERT A. NOLAN, in his official capacity as Cape May County Sherriff, et al., Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. GURBIR S. GREWAL, in his official capacity as Attorney General of the State of New Jersey, et al., Defendants-Appellees. On Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of New Jersey – No. 3:19-cv-18083 (Wolfson, C.J.) BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE CURRENT AND FORMER PROSECUTORS AND LAW ENFORCEMENT LEADERS AND FORMER ATTORNEYS GENERAL AND DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE OFFICIALS IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANTS-APPELLEES AND FOR AFFIRMANCE Chirag G. Badlani Mary B. McCord Caryn C. Lederer Shelby Calambokidis HUGHES SOCOL PIERS RESNICK INSTITUTE FOR CONSTITUTIONAL & DYM, LTD. ADVOCACY AND PROTECTION 70 West Madison St., Suite 4000 Georgetown University Law Center Chicago, IL 60602 600 New Jersey Avenue NW Tel.: (312) 580-0100 Washington, DC 20001 Tel.: (202) 662-9042 Counsel for Amici Curiae Case: 20-2754 Document: 39-2 Page: 2 Date Filed: 02/15/2021 Table of Contents INTEREST AND IDENTITY OF AMICI CURIAE .................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 2 ARGUMENT ........................................................................................................................ 5 I. New Jersey’s Immigrant Trust Directive Is Essential to Effective Law Enforcement .......................................................................................................... 5 A. Trust and Respect Between Communities and Law Enforcement Officials Are Thwarted When Individuals Fear Removal as a Consequence of Cooperation ........................................................................... -

NCSC Pandemic Webinar Summaries for 2020

NCSC Pandemic Webinar Summaries 2020 National Center for State Courts NCSC Pandemic Webinar Summaries for 2020 Chron. Webinar Title Date(s) Page in Sequence (Alphabetical) This Document 3rd Access to Justice Considerations for State and April 3rd, pg. 4 Local Courts as They Respond to COVID-19: A 2020 Conversation 17th Addressing Court Workplace Mental Health and June 25th, pg. 5 Well-Being in Tense Times 2020 32nd Administering Criminal Courts During the October pg. 7 Pandemic: Next Steps 29th, 2020 29th Approaches to Managing Juvenile Cases in the October 1st, pg. 8 COVID Era 2020 18th Back to the Future: Video Remote Interpreting June 30th, pg. 10 and Other Language Access Solutions in the 2020 Time of COVID 27th Court Management of Guardianships and September pg. 12 Conservatorships During the Pandemic 23rd, 2020 24th COVID-19 Business Litigation Grab Bag September pg. 14 14th, 2020 20th COVID-19 Commercial Contract Litigation July 20th, pg. 16 2020 10th COVID-19 and Courthouse Planning to Get May 15th, pg. 18 Back to Business Inside the Courthouse 2020 21st COVID-19 Labor and Employment Liability August 3rd, pg. 19 2020 22nd COVID-19 State Insolvency: Receiverships & August 10th, pg. 20 Assignment for the Benefit of Creditors 2020 9th Developing Plans for Expanding In-Person May 1st, pg. 22 Court Operations 2020 19th Essential Steps to Tackle Backlog and Prepare July 19th, pg. 24 for a Surge in New Cases 2020 11th Expanding Court Operations II: Outside the Box May 19th, pg. 26 Strategies 2020 33rd Fair and Efficient Handling of Consumer Debt November pg. -

A National Call to Action

A National Call to Action Access to Justice for Limited English Proficient Litigants: Creating Solutions to Language Barriers in State Courts July 2013 For further information contact: Konstantina Vagenas, Director/Chief Counsel Language and Access to Justice Initiatives National Center for State Courts 2425 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 350 Arlington, VA 22201-3326 [email protected] Additional Resources can be found at: www.ncsc.org Copyright 2013 National Center for State Courts 300 Newport Avenue Williamsburg, VA 23185-4147 ISBN 978-0-89656-287-5 This document has been prepared with support from a State Justice Institute grant. The points of view and opinions offered in this call to action are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policies or position of the State Justice Institute or the National Center for State Courts. Table of Contents Preface and Acknowledgments i Executive Summary ii Introduction iv Chapter 1: Pre-Summit Assessment 1 Chapter 2: The Summit 11 Plenary Sessions 12 Workshops 13 Team Exercises: Identifying Priorities and Developing Action Plans 16 Chapter 3: Action Steps: A Road Map to a Successful Language Access Program 17 Step 1: Identifying the Need for Language Assistance 19 Step 2: Establishing and Maintaining Oversight 22 Step 3: Implementing Monitoring Procedures 25 Step 4: Training and Educating Court Staff and Stakeholders 27 Step 5: Training and Certifying Interpreters 30 Step 6: Enhancing Collaboration and Information Sharing 33 Step 7: Utilizing Remote Interpreting Technology 35 Step 8: Ensuring Compliance with Legal Requirements 38 Step 9: Exploring Strategies to Obtain Funding 40 Appendix A: Summit Agenda 44 Appendix B: List of Summit Attendees/State Delegations 50 Preface and Acknowledgments Our American system of justice cannot function if it is not designed to adequately address the constitutional rights of a very large and ever-growing portion of its population, namely litigants with limited English proficiency (LEP).