Re-Locating the Spaces of Television Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OECD COMMUNICATIONS OUTLOOK 2001 Broadcasting Section

OECD COMMUNICATIONS OUTLOOK 2001 Broadcasting Section Country: Mexico Date completed: June 21, 2000 1 BROADCASTING Broadcasting services available 1. Please provide details of the broadcasting and cable television services available in your country. Infrastructure provision for Number of licensed Number of privately Number of public following service operators (2000) owned companies1 service organisations2 Terrestrial TV --- (National coverage3) Terrestrial TV 2251** 2051 200 (Local coverage4 only) Terrestrial radio --- (National coverage) Terrestrial radio 1500** 1242 258 (Local coverage only) Cable television service5 486 licensed operators * 486 0 It is permitted for more than one organisation to own and operate cable television in the same area. (Overbuilding is allowed) Analogue direct broadcast --- satellite (DBS) service Digital DBS service - - - MMDS 40 40 0 * There are neither concessions nor permits with national coverage in Mexico. Concessions are granted to local coverage. However, concessionaires tend to associate for national coverage. There are 5 national and 1 regional television networks. There are 20 regional radio networks. ** Includes “repeater stations”. 1 Defined as private sector companies holding one or more licences for service provision. 2 Including state-owned corporations or institutions holding one or more licences for service provision. 3 A service with national coverage is defined as a service by a group of television or radio stations distributing a majority of the same programming, that are licensed on a national or regional basis but collectively provide nation-wide coverage. Affiliating companies of the nation-wide broadcast network are included in this category. If new operators have been licensed to provide national coverage in the last three years but are at the stage of rolling out networks please include these operators in the total. -

US Army Wants to Play More Robust Role in Asia-Pacific

Msgr Gutierrez Zena Babao Bill Labestre With the 3 Kings, The Beauty of a New Year’s Good Health Can You Afford to Resolution .. p 8 .. p 10 Retire? .. p 6 JanuaryJanuary 3-9, 3-9,2014 2014 The original and first Asian Journal in America PRST STD U.S. Postage Paid Philippine Radio San Diego’s first and only Asian Filipino weekly publication and a multi-award winning newspaper! Online+Digital+Print Editions to best serve you! Permit No. 203 AM 1450 550 E. 8th St., Ste. 6, National City, San Diego County CA USA 91950 | Ph: 619.474.0588 | Fx: 619.474.0373 | Email: [email protected] | www.asianjournalusa.com Chula Vista M-F 7-8 PM CA 91910 US Army wants to play more robust role in Asia-Pacifi c Philstar.com | WASHING- TON, 1/1/2014 – The US Mexican drug cartel now Army wants to play a more “Dad, Are We Rich?” robust role in the Asia-Pacifi c in Phl – PDEA to reassert its relevance in the Arturo Cacdac Jr. said Mexico Philstar.com | MANILA, based on a true story region. was the latest foreign coun- 12/27/2013 - A Mexican drug The move came at a time try that has smuggled illegal cartel is now selling shabu when the Obama administra- drugs, particularly shabu, (methamphetamine) in the tion deemed the region to be into the country, in addition Philippines, the Philippine By Simeon G. Silverio, Jr. America’s next national secu- to China and West African Drug Enforcement Agency Publisher & Editor, rity priority, the Washington nations. -

Graeme Turner

Graeme Turner SURRENDERING THE SPACE Convergence culture, Cultural Studies and the curriculum This essay tests the claims made by some versions of convergence culture to be the next step forward for Cultural Studies. It does this by examining the teaching programmes that have been generated by various formations of convergence culture: programmes in new media studies, creative industries and digital media studies. The results of this examination are cause for concern: most of these programmes appear to have surrendered the space won for Cultural Studies in the university curriculum in favour of an instrumentalist focus on the training, rather than the education, of personnel to work in the emerging media industries. The essay argues therefore that while such developments may represent themselves as emerging from within Cultural Studies, in practice they have turned out to have very little to do with Cultural Studies at all. Keywords teaching Cultural Studies; curriculum; new media studies; creative industries; digital media studies Introduction Reservations about the hype around what we have come to call convergence culture are not new. Back in 2003, media historian Jeffery Sconce, bouncing off an account of a pre-modern example of popular hype, ‘tulipmania’,1 had this to say about the early warning signs from what was then called ‘digital culture’: I think most of us would be hard-pressed to think of a discipline in which more pages have been printed about things that haven’t happened yet (and may never) and phenomena that in the long run are simply not very important (Jennicam, anyone?). Of course, only an idiot would claim that digital media are not worthy of analysis, an assertion that would sadly replicate the hostility towards film and television studies encountered in the last century. -

US Gives Over 100 Military Vehicles to PH MANILA: the Philippines Is Receiving 114 They Would Be Deployed Soon

OFW-FPJPI holds Lahing Batangueno Christmas party, share celebrates ’versary 02blessings 03 to runaway www.kuwaittimes.net SUNDAY, DECEMBER 13, 2015 ‘Filipino Flash’ Donaire faces Juarez for super bantamweight crown Page 07 COC ni Poe kinansela ng Comelec MANILA: Kinansela na rin ng Commission on Elections (Comelec) First Division ang certificate of candidacy (COC) ni Sen. Grace Poe para sa pagtakbo nito sa pagkapangulo sa May 2016 elections. Ang botong 2-1 ng Comelec ay bunsod ng petitions na ini- hain nina Sen. Francisco Tatad, Prof. Antonio Contreras at dating US Law Dean Amado Valdez. Bumoto para kanselahin ang COC ni Poe ay sina Commissioners Rowena Guanzon at Luie Tito Guia habang lone dis- senter naman si Commissioner Christian Robert Lim. ‘Pacquiao picks Bradley for last fight’? MANILA: Manny Pacquiao has reportedly chosen Timothy Bradley, whom he has tangled with twice, as the opponent for his final fight on April 9 next year. David Anderson of The Mirror reported that Pacquiao bypassed Amir Khan and is going for a rubber match with Bradley, who defeated the Filipino icon in 2012 and lost to him in their MANILA: Customers buy Christmas decorations from a street stall at the farmer’s market in suburban Manila yesterday. The Philippines Asia’s bastion of Roman Catholicism, celebrates the world’s longest Christmas season starting on December 16 with dawn masses and ends on the first week of January. —AFP US gives over 100 military vehicles to PH MANILA: The Philippines is receiving 114 they would be deployed soon. The vehicles were offered as part of a US armoured vehicles donated by the United “Our forces are now more protected and military programme of giving away excess States, officials said, boosting the poorly- they will have more mobility because they will equipment, but the Philippines paid 67.5 mil- equipped military’s fight against various insur- be in a tracked vehicle,” that is more suited for lion pesos ($1.4 million) to cover transport gent groups in the country. -

Foreign Direct Investment in Latin America and the Caribbean Alicia Bárcena Executive Secretary

2010 Foreign Direct Investment in Latin America and the Caribbean Alicia Bárcena Executive Secretary Antonio Prado Deputy Executive Secretary Mario Cimoli Chief Division of Production, Productivity and Management Ricardo Pérez Chief Documents and Publications Division Foreign Direct Investment in Latin America and the Caribbean, 2010 is the latest edition of a series issued annually by the Unit on Investment and Corporate Strategies of the ECLAC Division of Production, Productivity and Management. It was prepared by Álvaro Calderón, Mario Castillo, René A. Hernández, Jorge Mario Martínez Piva, Wilson Peres, Miguel Pérez Ludeña and Sebastián Vergara, with assistance from Martha Cordero, Lucía Masip Naranjo, Juan Pérez, Álex Rodríguez, Indira Romero and Kelvin Sergeant. Contributions were received as well from Eduardo Alonso and Enrique Dussel Peters, consultants. Comments and suggestions were also provided by staff of the ECLAC subregional headquarters in Mexico, including Hugo Beteta, Director, and Juan Carlos Moreno-Brid, Juan Alberto Fuentes, Claudia Schatan, Willy Zapata, Rodolfo Minzer and Ramón Padilla. ECLAC wishes to express its appreciation for the contribution received from the executives and officials of the firms and other institutions consulted during the preparation of this publication. Chapters IV and V were prepared within the framework of the project “Inclusive political dialogue and exchange of experiences”, carried out jointly by ECLAC and the Alliance for the Information Society (@lis 2) with financing from the European -

Kathryn Bernardo Winning Over Her Self-Doubt Bernardo’S Story Is Not Just All About Teleserye Roles

ittle anila L.M.ConfidentialMARCH - APRIL 2013 Stolen Art on the Rise in the Philippines MANILA, Philippines - Art dealers and buyers beware: Criminal syndicates have developed a taste for fine art and, moving like a pack of wolves, they know exactly what to get their filthy paws on and how to pass the blame on to unsuspecting gallery staffers or art collectors. Many artists, art galleries, and collectors who have fallen victim to heists can attest to this, but opt to keep silent. But do their silence merely perpetuate the growing art thievery in the industry? Because he could no longer agonize silently after a handful of his sought-after creations have been lost KATHRYN to recent robberies and break-ins, sculptor Ramon Orlina gave the Inquirer pertinent information on what appears to be a new art theft modus operandi that he and some of the galleries carrying his works Bernardo have come across. Perhaps the latest and most brazen incident was a failed attempt to ransack the Orlina atelier Winning Over in Sampaloc early in February! ORLINA’S “Protector,” Self-Doubt stolen from Alabang design space Creating alibis Two men claiming to be artists paid a visit to the sculptor’s Manila workshop and studio while the artist’s workers Student kills self over Tuition were on break; they told the staff they were in search of sculptures kept in storage. UP president: Reforms under way after coed’s tragedy The pair informed Orlina’s secretary that they wanted to purchase a few pieces immediately and MANILA, Philippines - In death, and its student support system In a statement addressed to the asked to be brought to where smaller works were Kristel Pilar Mariz Tejada has under scrutiny, UP president UP community and alumni, Pascual housed. -

Tv Azteca, S Tv Azteca, S.A.B. De C.V

OFFERING CIRCULAR TV AZTECA, S.A.B. DE C.V. Medium Term Note Programme Due from Three Hundred and Sixty Days to Ten Years from the Date of Issue TV Azteca, S.A.B. de C.V. ("Azteca" or the "Issuer") may from time to time issue medium term notes (the "Notes") under the programme (the "Programme") described in this Offering Circular. All Notes having the same interest payment dates, issue price and maturity date, bearing interest at the same rate and the terms of which are otherwise identical constitute a "Series." The Notes will have the following characteristics: The Notes may be issued in any currency. The Notes will have maturities of not less than 360 days nor more than ten years. The maximum principal amount of all Notes from time to time outstanding under the Programme will not exceed US$500,000,000 (or its equivalent in other currencies calculated as described in the Programme Agreement). The Notes may be issued at their nominal amount or at a premium over or discount to their nominal amount and/or may bear interest at a fixed rate or floating rate. The Notes will be issued in either registered or bearer form. The Notes will be jointly and severally guaranteed by Azteca International Corporation, Azteca Novelas, S.A. de C.V., Estudios Azteca, S.A. de C.V., Inversora Mexicana de Producción, S.A. de C.V., Operadora Mexicana de Televisión, S.A. de C.V. and Televisión Azteca, S.A. de C.V. (the "Guarantors" and each a "Guarantor"). The Notes may be issued as unsecured Notes or as secured Notes. -

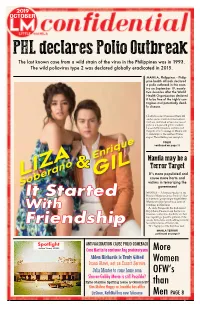

It Started Friendship

2019 OCTOBER PHL declares Polio Outbreak The last known case from a wild strain of the virus in the Philippines was in 1993. The wild poliovirus type 2 was declared globally eradicated in 2015. MANILA, Philippines -- Philip- pine health officials declared a polio outbreak in the coun- try on September 19, nearly two decades after the World Health Organization declared it to be free of the highly con- tagious and potentially dead- ly disease. Health Secretary Francisco Duque III said at a news conference that authori- ties have confirmed at least one case of polio in a 3-year-old girl in southern Lanao del Sur province and detected the polio virus in sewage in Manila and in waterways in the southern Davao region. Those findings are enough to POLIO continued on page 11 Enrique Manila may be a & Terror Target It’s more populated and LIZA GIL cause more harm and victims in terrorizing the Soberano government MANILA - A Deputy Speaker in the It Started House of Representatives thinks it’s like- ly that terror groups might target Metro Manila next after launching a series of bombings in Mindanao. With As such, Surigao del Sur 2nd district Rep. Johnny Pimentel said that law en- forcement authorities should be on their toes regarding a possible spillover of the attacks from down south, adding it would Friendship be costly in terms of human life. “It is highly possible that their next MANILA TERROR continued on page 9 Spotlight ANTI-VACCINATION CAUSE POLIO COMEBACK Au Bon Vivant, 1970’S Coco Martin to continue Ang probinsiyano More Alden Richards is Truly Gifted Ivana Alawi, not an Escort Service Women Julia Montes to come home soon OFW’s Sharon-Gabby Movie is still Possible? Kylie Maxine Spitting issue is Gimmick? than Kim Molina Happy sa Jowable box-office LizQuen, KathNiel has new Teleserye Men PAGE 8 1 1 2 2 2016. -

TV Azteca in Grupo Salinas

2Q 2021 This Presentation makes reference to certain non-IFRS measures. These non-IFRS measures are not recognized measures under IFRS, do not have a standardized meaning prescribed by IFRS and are therefore unlikely to be comparable to similar measures presented by other companies. These measures are provided as additional information to complement IFRS measures by providing further understanding of TV Azteca, S.A.B de C.V.´s (“TV Azteca”, “Azteca” or the “Company”) results of operations from a management perspective. Accordingly, they should not be considered in isolation nor as a substitute for analysis of TV Azteca's financial information reported under IFRS. Forward-Looking Statements This Presentation contains “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of the safe harbor provisions of the U.S. Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. Forward- looking statements can be identified by words such as: “anticipate,” “plan,” “believe,” “estimate,” “expect,” “strategy,” “should,” “will,” “seek,” “forecast,” and similar references to future periods. Examples of forward-looking statements include, among others, statements concerning the Company’s business outlook, future economic performance, anticipated profitability, revenues, expenses, or other financial items, market share, market growth rates, market demand, product or services growth. Forward-looking statements are neither historical facts nor assurances of future performance. Instead, they are estimates that reflect the best judgment of TV Azteca’s management based on currently available information. Because forward-looking statements relate to the future, they involve a number of risks, uncertainties and other factors that are outside of its control and could cause actual results to differ materially from those stated in such statements. -

Trust in Aquino Continues to Go Down 122415

! ! ! ! Trust in Aquino continues to go down December 24, 2015 at 12:01 am By Adelle Chua http://thestandard.com.ph/news/3main3stories/top3stories/195193/trust3in3 aquino3continues3to3go3down.html! FILIPINOS trusted President Benigno Aquino III less in December 2015 than they did in May and September, even as his performance and approval ratings for the same period were slightly higher than they were six months ago, according to The Standard Poll conducted by this newspaper’s resident pollster, Junie Laylo. President Benigno Aquino III The December survey was conducted between Dec. 4 and 12, with 1,500 biometrically registered voter respondents from the National Capital Region, Northern/ Central Luzon, Southern Luzon/Bicol, Visayas and Mindanao. The survey has a margin of error of plus or minus 2 percent on the national level. ! 1! ! ! ! ! Respondents across the country rated President Aquino’s performance at a net 43 percent, up from 28 percent in May and 40 percent in September. Aquino’s performance rating was highest in Mindanao, with net 66 percent in December from 44 percent in May and 57 percent in September. The next highest rating was given by residents of Northern and Central Luzon with net 45 percent in December from 24 percent and 32 percent in the two previous survey periods. The survey showed only a net 20 percent performance rating among Metro Manila residents. Similarly, respondents across the country gave a higher approval rating for President Aquino with net 41 percent in December from 24 percent in May and 35 percent in September. Respondents from Mindanao showed the highest approval at net 59 percent, up from 37 percent in May and 53 percent in September. -

British Cultural Studies: an Introduction, Third Edition

British Cultural Studies British Cultural Studies is a comprehensive introduction to the British tradition of cultural studies. Graeme Turner offers an accessible overview of the central themes that have informed British cultural studies: language, semiotics, Marxism and ideology, individualism, subjectivity and discourse. Beginning with a history of cultural studies, Turner discusses the work of such pioneers as Raymond Williams, Richard Hoggart, E. P. Thompson, Stuart Hall and the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies. He then explores the central theorists and categories of British cultural studies: texts and contexts; audience; everyday life; ideology; politics, gender and race. The third edition of this successful text has been fully revised and updated to include: • applying the principles of cultural studies and how to read a text • an overview of recent ethnographic studies • a discussion of anthropological theories of consumption • questions of identity and new ethnicities • how to do cultural studies, and an evaluation of recent research method- ologies • a fully updated and comprehensive bibliography. Graeme Turner is Professor of Cultural Studies at the University of Queensland. He is the editor of The Film Cultures Reader and author of Film as Social Practice, 3rd edition, both published by Routledge. Reviews of the second edition ‘An excellent introduction to cultural studies … very well written and accessible.’ John Sparrowhawk, University of North London ‘A good foundation and background to the development -

Annual Report 2007

ANNUAL REPORT 2007 Contact details: Centre for Critical and Cultural Studies Level 4 Forgan Smith Tower The University of Queensland St Lucia Qld AUSTRALIA 4072 Ph: 61 7 3364 9764 Fax: 61 7 3365 7184 Email: [email protected] Web: www.cccs.uq.edu.au TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 5 EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES ...................................................................... 6 Public Lecture Program .............................................................................................................. 6 Occasional Seminar Program.................................................................................................. 7 Symposium ........................................................................................................................................ 8 Media and Cultural Studies Meetings (MACS) .............................................................. 8 FEDERATION FELLOW PROJECT .......................................................... 9 ARC CULTURAL RESEARCH NETWORK .............................................. 9 VISITORS ................................................................................................... 10 Honorary Fellows ......................................................................................................................... 11 Visiting Scholars ........................................................................................................................... 11 Faculty Fellows