Rocket Internet Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Semi-Annual Report As at March 31St, 2016 Unideutschland XS Investment Company: Union Investment Privatfonds Gmbh

Semi-annual report as at March 31st, 2016 UniDeutschland XS Investment Company: Union Investment Privatfonds GmbH In case of discrepancy between the English and German version, the German version shall prevail. Contents Page Preface 3 UniDeutschland XS 6 Investment Company, Depositary, Distributors 12 and Paying Agents, Committees, Auditor 2 Preface Union Investment – devoted to your interests Dealing with the change in the markets The Union Investment Group manages assets of about EUR 265 A volatile capital market, changing regulatory requirements and billion, making it one of Germany's largest investment companies new customer demands are all challenges we are meeting for both private and institutional investors. It is a fund successfully. management expert within the cooperative finance association. About 4.1 million private and institutional investors have placed The six months under review began on an upward trend, after their trust in us as their partner for fund-based investments. concerns about growth in China in previous months levelled off and the Fed stated that it intended to continue with its planned Today, the idea behind the foundation of the group in 1956 is interest rate increases, although at a moderate pace. In more topical than ever: private investors should have the December 2015, the two large central banks, the ECB and the opportunity to benefit from economic developments – even with Fed eventually stayed true to their announcements, albeit in only small monthly savings contributions. The interests of these different directions. While the Europeans further eased their investors have always been our main concern and, together with monetary policy, the Fed decided to tighten its policy. -

3-Month 2015

3-Month Report 2015 2 Selected key figures 2015 2014 Jan. – March Jan. – March Change Net income (in 5 million) Sales 905.1 709.9 + 27.5% EBITDA 173.5 112.1 + 54.8% EBIT 119.1 89.7 + 32.8% EBT 112.3 86.2 + 30.3% EPS (in 1) 0.39 0.31 + 25.8% EPS before PPA amortization (in 1) 0.43 0.32 + 34.4% Balance sheet (in 5 million) Current assets 643.5 304.3 + 111.5% Non-current assets 2,956.7 976.7 + 202.7% Equity 1,230.6 369.3 + 233.2% Equity ratio 34.2 % 28.8 % Total assets 3,600.2 1,281.0 + 181.0% Cash flow (in 5 million) Operative cash flow 133.1 79.7 + 67.0% Cash flow from operating activities 369.6(1) 125.6 + 194.3% Cash flow from investing activities - 139.1 - 22.2 Free cash flow (1) 343.1(1) 115.9 + 196.0% Employees at the end of March (2) Total 7,902 6,747 + 17.1% thereof in Germany 6,379 5,128 + 24.4% thereof abroad 1,523 1,619 - 5.9% Share (in 5) Share price at the end of March (Xetra) 42.41 34.08 + 24.4% Customer contracts (in million) Access, total contracts 7.01 5.72 + 1.29 thereof Mobile Internet 2.78 2.09 + 0.69 thereof DSL complete (ULL) 3.95 3.27 + 0.68 thereof T-DSL / R-DSL 0.28 0.36 - 0.08 Business Applications, total contracts 5.82 5.73 + 0.09 thereof in Germany 2.40 2.38 + 0.02 thereof abroad 3.42 3.35 + 0.07 Consumer Applications, total accounts 34.47 33.84 + 0.63 thereof with Premium Mail subscription 1.83 1.86 - 0.03 thereof with Value-Added subscription 0.35 0.33 + 0.02 thereof free accounts 32.29 31.65 + 0.64 (1) Free cash flow is defined as net cash inflows from operating activities, less capital expenditures, plus payments from disposals of intangible assets and property, plant and equipment; cash flow from operating activities and free cash flow Q1/2015 including the capital gains tax refund of 1 326.0 million (2) The headcount statistics of United Internet AG were revised as of June 30, 2014 and now disclose only active employees. -

INVITATION BERENBERG Is Delighted to Invite You to Its

INVITATION BERENBERG is delighted to invite you to its EUROPEAN CONFERENCE 2017 on Monday 4th – Thursday 7th December 2017 at Pennyhill Park Hotel & Spa London Road • Bagshot • Surrey • GU19 5EU • United Kingdom LIST OF ATTENDING COMPANIES (SUBJECT TO CHANGE) Automotives, Chemicals, Construction and Metals & Mining Banks, Diversified Financials, Insurance and Real Estate (cont’d) Capital Goods & Industrial Engineering and Aerospace & Defence ArcelorMittal SA Lloyds Banking Group Plc* GKN Plc* Balfour Beatty Plc NewRiver REIT Plc* Jungheinrich AG BASF SE* Nordea Bank AB KION GROUP AG* Bekaert SA Patrizia Immobilien AG* Krones AG Clariant AG* Phoenix Group Holdings* Meggitt plc * Covestro* RBS Plc* NORMA Group SE Croda International Plc Sampo Oyj* OSRAM Licht AG* Elementis Plc* St James’s Place Plc PALFINGER AG* Elringklinger AG Svenska Handelsbanken AB QinetiQ Plc Evonik Industries AG* Tryg A/S Rational AG HeidelbergCement AG* Unibail-Rodamco SE* Rheinmetall AG* HOCHTIEF AG* Vonovia SE* Rolls-Royce Holdings Plc* Johnson Matthey Plc* SAF-HOLLAND SA Kingspan Group Plc* Business Services, Leisure and Transport & Logistics Schneider Electric SA Klöckner & Co SE* Altran Technologies SA* Schoeller-Bleckmann Oilfield Equipment AG Lanxess AG* AP Moller Maersk A/S* Senvion SA* Lenzing AG Brenntag AG SGL Carbon SE* Linde AG* Compass Group Plc* Stabilus SA Novozymes A/S* DCC Plc* va-Q-tec AG PORR AG* Deutsche Post AG Varta AG Royal DSM NV* Elis SA VAT Group AG* Siltronic AG Fuller, Smith & Turner Plc* Vossloh AG* Travis Perkins Plc* Hapag-Lloyd AG -

Presentation of the Second Quarter of 2017 21 July 2017 Agenda

PRESENTATION OF THE SECOND QUARTER OF 2017 21 JULY 2017 AGENDA A Operating Companies’ Performance TODAY’S PRESENTERS B Investment Management Activities Joakim Andersson Acting CEO, Chief Financial Officer C Kinnevik’s Financial Position Chris Bischoff Senior Investment Director D Summary Considerations Torun Litzén Director Corporate Communication Q2 2017 HIGHLIGHTS: HIGH INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT ACTIVITY AND NEW KINNEVIK CEO APPOINTED OPERATING COMPANIES’ PERFORMANCE . E-Commerce: New customer offerings and scale benefits supported continued growth and profitability improvements . Communication: Continued mobile data adoption drove revenue and customer growth . Entertainment: The shift in consumer video consumption towards on demand and online entertainment products continued and drove growth . Financial Services: Product development and new partnerships supported strong customer growth . Healthcare: Strong user growth driven by strategic partnerships, and further investments made to improve the customer proposition INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT ACTIVITIES . Total investments of SEK 3.9bn in the second quarter, whereof SEK 3.7bn for a 18.5% stake in Com Hem . Total divestments of SEK 3.1bn, whereof: . SEK 2.1bn (EUR 217m) from the sale of Kinnevik’s remaining shareholding in Rocket Internet . SEK 1.0bn (USD 115m) from the sale of Kinnevik’s remaining shareholding in Lazada . On 21 July, Kinnevik announced an investment of USD 65m in Betterment, increasing the ownership to 16% FINANCIAL POSITION . Net Asset Value of SEK 81.9bn (SEK 298 per share), up SEK 2.4bn or 3% during the quarter led by a SEK 1.9bn increase from Zalando and a SEK 1.2bn increase from Tele2 including dividend received. Adding back dividend paid of SEK 2.2bn, the value increase was 6% during the quarter . -

Individual Financial Statements Berlin 2018

INDIVIDUAL FINANCIAL STATEMENTS BERLIN 2018 – HelloFresh SE – INDIVIDUAL FINANCIAL STATEMENTS BERLIN 2018 HELLOFRESH SE, BERLIN | BALANCE SHEET AS OF 31 DECEMBER 2018 Assets 31. December 2017 EUR EUR EUR A. Fixed assets I. Intangible assets 1. Internally generated software 3,025,425.81 3,542,879.14 Concessions, industrial property rights and similar rights 2. and assets, and licenses in such rights and assets 662,820.99 877,285.68 3 Assets under construction 870,291.36 208,979.03 4,558,538.16 4,629,143.85 II. Property, plant and equipment Other equipment, furniture and fixtures 1,658,265.72 1,029,995.25 1,658,265.72 1,029,995.25 III. Financial assets 1. Shares in affiliates 52,383,239.28 7,078,064.87 2. Loans to affiliates 328,595,116.28 265,986,336.61 3. Other financial assets 34,418.39 303,062.32 381,012,773.95 273,367,463.80 387,229,577.83 279,026,602.90 B. Current assets I. Receivables and other assets 1. Trade receivables due from affiliates 16,896,499.08 19,611,240.40 2. Other assets 3,557,909.33 3,154,501.00 20,454,408.41 22,765,741.40 II. Cash on hand and bank balances 149,186,057.74 294,528,749.37 169,640,466.15 317,294,490.77 C. Prepaid expenses 2,245,616.67 781,662.78 559,115,660.65 597,102,756.45 4 HelloFresh SE INDIVIDUAL FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2018 Equity and liabilities 31. -

Paice MONITOR Market, Technology, Innovation Imprint

PAiCE MONITOR Market, Technology, Innovation Imprint Published by PAiCE Scientific Assistance iit – Institut für Innovation und Technik in der VDI / VDE Innovation + Technik GmbH Peter Gabriel Steinplatz 1 10623 Berlin [email protected] www.paice.de Authors Birgit Buchholz | 030 310078-164 | [email protected] Peter Gabriel | 030 310078-206 | [email protected] Dr. Tom Kraus | 030 310078-5615 | [email protected] Dr. Matthias Künzel | 030 310078-286 | [email protected] Stephan Richter | 030 310078-5407 | [email protected] Uwe Seidel | 030 310078-181 | [email protected] Dr. Inessa Seifert | 030 310078-370 | [email protected] Dr. Steffen Wischmann | 030 310078-147 | [email protected] Design and layout LoeschHundLiepold Kommunikation GmbH Hauptstraße 28 | 10827 Berlin [email protected] Status April 2018 PAiCE MONITOR Market, Technology, Innovation 4 PAiCE MONITOR Inhalt 1 Introduction . 6 2 The Robotics cluster – Service robotics for industry, services and end customers . .. 8 2.1 Market analysis .......................................................8 2.2 Start-up environment ..................................................10 2.3 State of the art .......................................................12 2.4 R&D developments ...................................................14 2.5 Projects of the Robotics cluster ..........................................17 BakeR – Modular system for cost-efficient, modular cleaning robots ................18 QBIIK – Autonomous, learning logistics robot with gripper system -

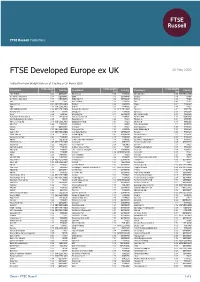

FTSE Publications

2 FTSE Russell Publications 20 May 2020 FTSE Developed Europe ex UK Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 31 March 2020 Index weight Index weight Index weight Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country (%) (%) (%) 1&1 Drillisch 0.02 GERMANY Biomerieux 0.09 FRANCE Ems Chemie I 0.08 SWITZERLAND A P Moller - Maersk A 0.07 DENMARK BMW 0.3 GERMANY Enagas 0.09 SPAIN A P Moller - Maersk B 0.11 DENMARK BMW AG Pref 0.04 GERMANY Endesa 0.12 SPAIN A2A 0.04 ITALY BNP Paribas 0.6 FRANCE Enel 0.99 ITALY Aalberts NV 0.04 NETHERLANDS Boliden 0.09 SWEDEN Engie 0.31 FRANCE ABB 0.58 SWITZERLAND Bollore 0.05 FRANCE Eni 0.46 ITALY ABN AMRO Bank NV 0.06 NETHERLANDS Boskalis Westminster 0.03 NETHERLANDS Epiroc A 0.11 SWEDEN Acciona S.A. 0.04 SPAIN Bouygues 0.11 FRANCE Epiroc B 0.07 SWEDEN Accor 0.09 FRANCE Brenntag AG 0.11 GERMANY EQT Partners AB 0.04 SWEDEN Ackermans & Van Haaren 0.05 BELGIUM Bureau Veritas S.A. 0.1 FRANCE Equinor ASA 0.23 NORWAY ACS Actividades Cons y Serv 0.09 SPAIN Buzzi Unicem 0.02 ITALY Ericsson A 0.01 SWEDEN Adecco Group AG 0.11 SWITZERLAND Buzzi Unicem Rsp 0.01 ITALY Ericsson B 0.45 SWEDEN Adevinta 0.04 NORWAY CaixaBank 0.12 SPAIN Erste Group Bank 0.1 AUSTRIA Adidas 0.8 GERMANY Campari 0.07 ITALY EssilorLuxottica 0.58 FRANCE Adyen 0.41 NETHERLANDS Capgemini SE 0.24 FRANCE Essity Aktiebolag B 0.34 SWEDEN Aegon NV 0.08 NETHERLANDS Carl Zeiss Meditec 0.07 GERMANY Eurazeo 0.04 FRANCE Aena SME SA 0.14 SPAIN Carlsberg (B) 0.21 DENMARK Eurofins Scienti 0.1 FRANCE Aeroports de Paris 0.05 FRANCE Carrefour 0.17 FRANCE Euronext 0.08 FRANCE Ageas 0.14 BELGIUM Casino Guichard Perrachon 0.04 FRANCE Eutelsat Communications 0.04 FRANCE Ahold Delhaize 0.47 NETHERLANDS Castellum 0.08 SWEDEN Evonik Industries AG 0.07 GERMANY AIB Group 0.02 IRELAND CD Projekt SA 0.08 POLAND Exor NV 0.1 ITALY Air France-KLM 0.02 FRANCE Cellnex Telecom SAU 0.23 SPAIN Fastighets AB Balder B 0.06 SWEDEN Air Liquide 1.09 FRANCE Chr. -

Annual Report 2019

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 – HelloFresh SE – HELLOFRESH AT A GLANCE 3 months 3 months 12 months 12 months ended ended ended ended Key Figures 31-Dec 19 31-Dec 18 YoY growth 31-Dec 19 31-Dec-18 YoY growth Key Performance Indicators Group Active customers (in millions) 2.97 2.04 45.3% Number of orders (in millions) 10.54 7.42 42.0% 37.45 27.07 38.3% Orders per customer 3.6 3.6 - Meals (in millions) 79.6 54.7 45.6% 281.1 198.4 41.7% Average order value (EUR) (Exc. Retail) 48.6 48.6 0.0% Average order value constant currency (EUR) (Exc. Retail) 47.8 48.6 (1.7%) USA Active customers (in millions) 1.78 1.09 63.0% Number of orders (in millions) 5.98 3.84 55.7% 20.74 14.94 38.8% Orders per customer 3.4 3.5 (4.5%) Meals (in millions) 40.5 25.2 60.4% 138.2 99.2 39.3% Average order value (EUR) (Exc. Retail) 49.1 50.6 (3.0%) Average order value constant currency (EUR) (Exc. Retail) 47.6 50.6 (5.9%) International Active customers (in millions) 1.18 0.95 24.9% Number of orders (in millions) 4.56 3.58 27.4% 16.71 12.13 37.8% Orders per customer 3.9 3.8 2.0% Meals (in millions) 39.1 29.4 32.9% 142.9 99.2 44.0% Average order value (EUR) (Exc. Retail) 48.0 46.4 3.3% Average order value constant currency (EUR) (Exc. -

Equity Capital Markets Team Germany

Equity Capital Markets Team Germany allenovery.com Our strength is our experience with complex assignments Capital markets are difficult to predict and present serious challenges to investors and issuers. Both investment banks and corporate entities need competent support, especially when it comes to developing innovative and tailor-made structures; they need lawyers who have the necessary specialist knowledge coupled with the practical experience for implementing their ideas. This is why Allen & Overy’s Equity Capital Markets team comprises only acknowledged experts who, thanks to their experience and expertise, ensure that we are very well versed with the ins and outs of the market and offer top-quality advice to our clients at all times. Equity Deal Ranked 1st Tier 1 of the Year EMEA Equity IPO: Chambers Global and IFLR Europe Awards Issuer by value, Legal 500 2020 2016, 2017, 2018 Bloomberg Q3 2020 “Clients speak highly of the team’s The team “handled a very responsiveness and availability, complex, multi-jurisdictional and describe the lawyers as ‘reliable, transaction brilliantly, with a very client-oriented and pragmatic’!” fast turnaround and a focus on Chambers Europe Germany 2019 the core issues at hand.” (Client) Chambers Europe Germany 2020 2 Equity Capital Markets Team Germany | 2020 What you can Our expect from us expertise Leading ECM practice Our Equity Capital Markets team in Germany provides you with access to excellent, Our German Equity Capital Markets team, led by experienced lawyers with a track record of Dr Knut Sauer, has advised on many of the most high- advising our clients on some of the most profile ECM transactions in Germany in recent years. -

Profitieren Vom Megatrend Urbanisierung Umbaupläne

Der Newsletter für Kapitalanleger. Mit Wissen zu Werten. # 10 Börsenpflichtblatt der Börsen Berlin, Düsseldorf, Hamburg, 2014 Hannover, München und Stuttgart # 10 2014 IVU Traffic Technologies AG Profitieren vom Megatrend Urbanisierung Seite 6 Bayer AG FINDE UNS Umbaupläne erzeugen AUF FACEBOOK www.facebook.com/ Wachstumsfantasie AnlegerPlus Seite 12 HV-Bericht Nach dem BuG ist vor dem Squeeze out Seite 20 Kurzmeldungen Nebenwerte Realdepot Neu an der Börse: Zalando und Rocket Internet | RIB Software AG Turbulente Zeiten Beliebt bei Privatanlegern | Privatinvestortag | FORTEC Elektronik AG Europäischer ETF-Markt Setzen Sie auf das, was immer bleibt: Setzen Sie auf Edelmetalle! In unserem Edelmetallshop Lagern Sie Ihre Barren und ... oder erstellen Sie sich präsentieren wir Ihnen die Münzen zu unschlagbar einen Sparplan und sparen ganze Welt der Anlagemetalle günstigen Konditionen im Sie Monat für Monat aufs von ausgezeichneter Qualität! Hochsicherheitslager ein... große Goldvermögen! APPsolut goldrichtig Die neue Handelsapp von Ophirum jetzt kostenlos downloaden! :HLWHUH,QIRUPDWLRQHQdžQGHQ6LHDXIXQVHUHU:HEVHLWHXQWHUwww.ophirum.de! Ophirum Commodity GmbH, Thurn-und-Taxis-Platz 6, 60313 Frankfurt am Main, ©2014 Ophirum Commodity GmbH. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. EDITORIAL Anzeige Abgeschossene IPO-Raketen Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, mit großem Tamtam wurden sie den ganzen September über promotet: Die Börsengänge von Zalando und Rocket Internet. Euphori- sche Meldungen wie „Das Angebot war am obersten Ende der Preisspanne deutlich mehr als zehnfach überzeichnet“ bei Zalando oder eine „außergewöhnlich hohe Investorennach- frage“ bei Rocket Internet ließen erwarten, dass die zwei Neuemissionen der Internet- brüder Samwer ein großer Erfolg werden könnten. Darauf deuteten auch die Grau- marktkurse vor den Tagen der jeweiligen Erstnotiz hin, die durchweg rund 30 % über Setzen Sie auf das, was immer bleibt: dem Emissionspreis lagen. -

NOAH Berlin 2018

Table of Contents Program 6 Venture Capital 10 Growth 107 Buyout 124 Debt 137 Trading Comparables 143 2 Table of Contents Venture Capital Buyout 3TS Capital Partners 11 Frog Capital 50 SevenVentures 90 Apax 125 83North 12 General Catalyst 51 Speedinvest 91 Ardian 126 Accel Partners 13 German Media Pool 52 SpeedUp Venture Capital 92 Bain Capital 127 Acton Capital Partners 14 German Startup Group 53 Group Capvis Equity Partners 128 Astutia Ventures 15 Global Founders Capital 54 STS Ventures 93 EQT Partners 129 Atlantic Labs 16 GPS Ventures 55 Swisscom Ventures 94 FSN Capital Partners 130 AVentures Capital 17 GR Capital 56 TA Ventures 95 GENUI 131 AXA Venture Partners 18 Griffon Capital 57 Target Partners 96 KKR 132 b10 I Venture Capital 19 High-Tech Gruenderfonds 58 Tengelmann Ventures 97 Macquarie Capital 133 BackBone Ventures 20 HV Holtzbrinck Ventures 59 Unternehmertum Venture 98 Maryland 134 Balderton Capital 21 IBB 60 Capital Partners Oakley Capital 135 Berlin Technologie Holding 22 Beteiligungsgesellschaft Vealerian Capital Partners 99 Permira 136 idinvest Partners 61 Ventech 100 Bessemer Venture 23 Partners InMotion Ventures 62 Via ID 101 BCG Digital Ventures 24 Innogy Ventures 63 Vito Ventures 102 BFB Brandenburg Kapital 25 Inovo.vc 64 Vorwerk Ventures 103 Intel Capital 65 W Ventures 104 BMW iVentures 26 Iris Capital 66 WestTech Ventures 105 Boerste Stuttgart - Digital 27 Kizoo Technology Capital 67 XAnge 106 Ventures Debt btov Partners 28 Kreos Capital 68 LeadX Capital Partners 69 Buildit Accelerator 29 Lakestar 70 CapHorn Invest -

NOAH Digital

Curated Introductions for Industry Leaders 10 Years Growth Story Changemakers. Introducing the New NOAH Concept Global Launch Collapses and NOAH at STATION-Berlin Jun-20 Arises Jun-19 2008 NOAH Conference Expands to Berlin The Beginning! Investor Partner Program NOAH Digital Tempodrom, Jun-15 First NOAH Conference Jan-19 Jun-20 Takes Place in London Eric Schmidt on NOAH Stage Hilton Park Lane, Nov-09 NOAH Conference NOAH 2015 Announces Expansion to Zurich Apr-19 NOAH to Host the Dara Khosrowshahi & Family Office Circle Al Gore on NOAH Stage Conference & Product & Conference Conference First NOAH Matchmaking NOAH Connect App v1: Bringing the NOAH 2018 Service Famous Networking Online Early 2021 Oct-12 May-16 Speakers 35 77 142 236 272 332 460 574 703 872 1,144 Attendees 431 862 1,632 2,911 3,794 4,647 6,817 9,327 11,521 14,199 17,262 Investors Unique 171 276 475 683 873 1,065 1,435 1,842 2,166 2,620 2,977 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 (Jul-19) (May-14) (Sep-16) (Aug-17) NOAH advises EMK NOAH advises Au10tix shareholders NOAH advises Yad2 / shareholders NOAH advises Oakley Capital on its Capital on its on the $60m investment at a $260m in its $228m sales to Axel Springer partial sale of Parship to Pro7 acquisition of Luminati valuation led by TPG (Nov-19) (Apr-09) (May-12) (Sep-14) (Oct-16) NOAH advises MagicLab on NOAH advises Fotolia on its $80m NOAH advises Fotolia on its NOAH advises Käuferportal / the acquisition of a 79% stake NOAH advises Facile.it / shareholders majority sale to TA Associates investment from KKR shareholders in the sale to (Jul-18) by Blackstone.