Downloaded on 2017-02-12T14:01:46Z DP ,Too 0 OO'dtj

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0 Golden Hour

GOLDEN HOUR - In the hour after sunrise or the hour before sunset. In light diffused, the party in apricot hues, refused, to end. 0 CONTENTS Cocktails .........................................................................................................................3-4 Aperitif .............................................................................................................................. 5 Beer .................................................................................................................................... 5 Champagne and Wine Selection .............................................................................. 6 Champagne ...................................................................................................................... 7 Champagne Rosé ........................................................................................................... 8 Gin………………………………………………………………………………………………9-10 Vodka .............................................................................................................................. 11 Tequila, Mezcal .................................................................................................... 11-12 Rum, Cachaca ........................................................................................................ 13-14 Whisky Collection ............................................................................................... 15-18 Cognac .................................................................................................................... -

A Miscellany of Irish Proverbs

H^-lv- Aj^ HcJtjL^SM, 'HLQ-f- A MISCELLANY OF IRISH PROVERBS A MISCELLANY IRISH PROVERBS COLLRCTED AND RDITKD BY THOMAS F. O'RAHILLY, M.A. M.R.I. A.; PROFESSOR OF IRISH IN THE UNIVERSITY OF DUBLIN DUBLIN THE TAIvBOT PRESS LIMITED 85 TALBOT STREET J 922 Sapientiam omnium antiquorum exquiret sapiens, et in prophetis vacabit. Narrationem virorum nominatornmi con- servabit, et in veisutias parabolarum simul introibit, Occulta proverbiorum exquiret, et in ab- sconditis parabolarum conversabitur. —ECCI,I. xxxix. 1-3. ' * IT PREFACE In the present book I have made an at- tempt, however modest, to approach the study of Irish proverbs from the historic and comparative points of view. Its princi- pal contents are, first, the proverbs noted by Mícheál Og Ó Longain about the year 1800, and, secondly, a selection of proverbs and proverbial phrases drawn from the literature of the preceding thousand years. I have added an English translation in every case. Sometimes, as will be observed, the Irish proverbs corre-spoud closely to English ones. When this is so, I have given (between quo- tation marks) the English version, either instead of or in addition to a translation. While it is probable that most of the pro- verbs thus common to the two languages have been borrowed into Irish from English, still it should be borne in mind that many of them possess an international character, and are as well known in Continental languages as they are in English or Irish. I have, however, refrained from quoting these Continental versions ; any reader who is interested in them will find what he wants elsewhere, and it would have been a waste of space for me to attempt to give them here. -

Eight Generations of Hennessys N°1 Eight Generations of Hennessys

N°1 EIGHT GENERATIONS OF HENNESSYS N°1 EIGHT GENERATIONS OF HENNESSYS Richard, James, Maurice... 1724-1800: Richard Hennessy The patriarch and founder. After fighting in the army of King Louis XV, he settled in Cognac and created the Hennessy trading com- pany in 1765. 1765-1843: James-Jacques Hennessy The visionary. With his partner, Samuel Turner, Richard’s oldest son structured the company and determined the criteria that would define the brand’s identity: expertise, the will to lead, a dedication to excellence – from the quality of the barrels to the methods of shipping. 1795-1845: James Hennessy, then in 1800-1879: Auguste Hennessy The sons of “James I” inherited values they would pass on to the Hennessy “dynasty”. In particular, the spirit of conquest that, beginning in the nineteenth century, enabled the Maison to expand across five continents. 1835-1905: Maurice Hennessy The innovator who worked in partnership with his Master Blender Emile Fillioux, introducing the star-based classification system, revolutionising shipping methods, creating X.O. At the end of the 1880s, his initiative was decisive in saving Hennessy from the phyl- loxera crisis that had started in the Seventies. With the help of scientists, his son James continued his work, benefitting the entire industry. 1867-1945:James Hennessy, then in 1874-1944:Jean Hennessy James and Jean gave their all to speed up the restoration of the Charente vineyards, decimated by phylloxera, and to reorganise the cognac industry in such a way that it could bounce back under optimum conditions. James was a senator for Charente and Jean a député, a minister and an Ambassador of France. -

De Vesci Papers

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 89 DE VESCI PAPERS (Accession No. 5344) Papers relating to the family and landed estates of the Viscounts de Vesci. Compiled by A.P.W. Malcomson; with additional listings prepared by Niall Keogh CONTENTS INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...........................................................6 I TITLE DEEDS, C.1533-1835 .........................................................................................19 I.i Muschamp estate, County Laois, 1552-1800 ............................................................................................19 I.ii Muschamp estates (excluding County Laois), 1584-1716........................................................................20 I.iii Primate Boyle’s estates, 1666-1835.......................................................................................................21 I.iv Miscellaneous title deeds to other properties c.1533-c. 1810..............................................................22 II WILLS, SETTLEMENTS, LEASES, MORTGAGES AND MISCELLANEOUS DEEDS, 1600-1984 ..................................................................................................................23 II.i Wills and succession duty papers, 1600-1911 ......................................................................................23 II.ii Settlements, mortgages and miscellaneous deeds, 1658-1984 ............................................................27 III LEASES, 1608-1982 ........................................................................................................35 -

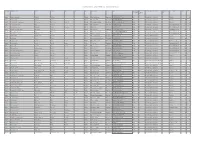

Post Primary Schools Within a 160KM Radius of Maynooth University

Post Primary Schools within a 160KM radius of Maynooth University Roll Number Official School Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Address 4 County Principal Name Phone Email School Gender Pupil Irish Classification - Post Primary Fee Paying School Ethos/Religion FEMALE MALE - Post Primary Attendance (Y/N) Type 61120E St Mary's Academy CBS Station Rd Carlow CARLOW MR. PAUL FIELDS 0599142419 [email protected] Boys Day No subjects taught through Irish N CATHOLIC 583 61130H St Mary's Knockbeg College Knockbeg Co. Carlow CARLOW MR. MICHAEL CAREW 0599142127 [email protected] Boys Day No subjects taught through Irish N CATHOLIC 411 61140K St. Leo's College Dublin Road Carlow CARLOW MISS CLARE RYAN 0599143660 [email protected] Girls Day No subjects taught through Irish N CATHOLIC 966 61141M Presentation College Askea Carlow Co. Carlow CARLOW MR. RAYMOND MURRAY 0599143927 [email protected] Mixed Day No subjects taught through Irish N CATHOLIC 370 354 61150N Presentation / De La Salle College Royal Oak Road Muine Bheag Co. Carlow CARLOW MR. GERARD WATCHORN 0599721860 [email protected] Mixed Day No subjects taught through Irish N CATHOLIC 283 313 70400L Borris Vocational School Borris Co Carlow CARLOW Mr John O'Sullivan 0599773155 [email protected] Mixed Day No subjects taught through Irish N INTER DENOMINATIONAL 237 269 70410O Coláiste Eoin Hacketstown Co Carlow CARLOW Pauline Egan 0596471198 [email protected] Mixed Day No subjects taught through Irish N INTER DENOMINATIONAL 111 122 70420R Carlow Vocational -

Research Guide for Archival Sources of Smock Alley Theatre, Dublin

Research Guide for Archival Sources of Smock Alley theatre, Dublin. October 2009 This research guide is intended to provide an accessible insight into the historical, theatrical and archival legacy of Smock Alley theatre, Dublin. It is designed as an aid for all readers and researchers who have an interest in theatre history and particularly those wishing to immerse themselves in the considerable theatrical legacy of Smock Alley theatre and it’s array of actors, actresses, directors, designers, its many scandals and stories, of what was and is a unique theatrical venue in the fulcrum of Dublin’s cultural heart. Founded in 1662 by John Ogilby, Smock Alley theatre and stage was home to many of the most famous and talented actors, writers and directors ever to work and produce in Ireland, England, Scotland and Wales, throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth century. Celebrated players included Peg Woffington, David Garrick, Colley Cibber, Spranger Barry and George Ann Bellamy. Renowned managers and designers such as John Ogilby, Thomas Sheridan, Louis De Val and Joseph Ashbury would help cement the place of Smock Alley theatre as a venue of immense theatrical quality where more than just a play was produced and performed but more of a captivating, wild and entertaining spectacle. The original playbills from seventeenth century productions at Smock Alley detail many and varied interval acts that often took place as often as between every act would feature singing, dancing, farce, tumbling, juggling and all manner of entertainment for the large public audience. Smock Alley was celebrated for its musical and operatic productions as well as its purely dramatic performances. -

VV-J 0 32-1450 M-Uww U V W a Chapter of Hitherto Unwritten

172 2008 PRE FA CE . The following H ist ory of a family numerous and I prosperous beyond recount, will, hope , prove acceptable no w to their descendants . These are to be found in all classes of society , and many have forgotten all about their forefathers and have not even a tradition remain i ing. Nay, members of this family who st ll live as county families in Ireland have become so culpably careless that a few generations is the limit of their d knowle ge . It will show the difficulty of the historian and n d o f genealogist, here at least whe it is state that George Lewis Jones , who was Bishop of this Diocese 1774— 1790 I not , could gather a particle of informa I tion but the meagre facts have stated . ! I PRE FACE . The transmission of physical conformation and facial expression , as well as that of moral qualities and defects , is an interesting study to the philosopher . In some u families you can trace for cent ries the same expression, featurmes and color, often the same height and very often li the sa e moral and intellectual qua ties . As a general u - rule, the feat res of this wide spread family , no matter i whether rich or poor, gifted or gnorant , are marked n by peculiar characteristics that, o ce seen and noted . N . cannot well be forgotten Captain Jones, R , M P I for Londonderry, whom knew when a boy, now Rear Admiral Sir Lewis Tobias Jones, the Rev . Thomas of I w J . -

Irish Literature, 1750–1900

Wright: Irish Literature 1750–1900 9781405145190_4_001 Page Proof page 131.7.2007 3:38pm Irish Literature, 1750–1900 Wright: Irish Literature 1750–1900 9781405145190_4_001 Page Proof page 231.7.2007 3:38pm Wright: Irish Literature 1750–1900 9781405145190_4_001 Page Proof page 331.7.2007 3:38pm Thomas Sheridan (1719–1788) Thomas Sheridan, probably born in Dublin but Humble Appeal also included a proposal for a possibly in Co. Cavan, was the son of another national theater in Dublin that would be publicly Thomas Sheridan (clergyman and author) and administered and ensure fair treatment of theater the godson of Jonathan Swift (a close friend of workers. the family). He may have been a descendant of As a dramatist, Sheridan mostly adapted other Denis Sheridan (c.1610–83), a native Irish authors’ works, as was common in his day; he speaker who assisted in the translation of the adapted, for instance, Coriolanus (1755) from Old Testament into Irish as part of Bishop texts by English authors William Shakespeare Bedell’s efforts to make the Church of Ireland and James Thomson. His enduringly popular accessible to Irish speakers. The younger Thomas farce The Brave Irishman: Or, Captain O’Blunder Sheridan worked primarily in the theater, as was published and staged throughout the second actor, manager, playwright, and author of var- half of the eighteenth century and compactly ious tracts related to theater reform, but also abbreviated in three double-columned pages published on other subjects, including British for the Cabinet of Irish Literature a century Education: Or the Source of Disorders in Great later. -

Cognac Directory FINAL.Pdf

NICHOLAS FAITH’S GUIDE TO COGNAC NICHOLAS FAITH’S GUIDE TO COGNAC CONTENTS Introduction 5 Land, vine, wine 19 The personality of cognac 41 The producers and their brandies 57 Cognac recipes 122 INTRODUCTION THE UNIQUENESS OF COGNAC In winter you can tell you are in cognac country when you turn off the N10, the old road between Bordeaux and Paris at the little town of Barbezieux and head towards Cognac. The landscape does not change dramatically; it is more rounded, perhaps a little more hilly, than on the road north from Bordeaux, and the vines are thicker on the ground. But the major indicator has nothing to do with the sense of sight. It has to do with the sense of smell. During the distillation season from November to March the whole night-time atmosphere is suffused with an unmistakable aroma, a warm smell that is rich, grapey, almost palpable. It emanates from dozens of otherwise unremarkable groups of farm buildings, distinguished only by the lights burning as the new brandy is distilled. Cognac emerges from the gleaming copper stills in thin, transparent trickles, tasting harsh and oily, raw yet recognisably the product of the vine. If anything, it resembles grappa; but what for the Italians is a saleable spirit is merely an intermediate product for the Cognacais. Before they consider it ready for market it has to be matured in oak casks. Most of the spirits, described by the more poetically minded locals as ‘sleeping beauties’, are and dashed the precious liquid to the floor to ensure that destined to be awakened within a few years and sold off as the glass was free from impurities. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. John Morrill, ‘The Fashioning of Britain’, in Steven Ellis and Sarah Barber (eds), Conquest and Union: Fashioning a British State 1485–1725 (Harlow, 1995). 2. Felicity Heal, ‘Mediating the Word: Language and Dialects in the British and Irish Reformations’, Journal of Ecclesiastical History 56 (2005). 3. J. A. Watt, ‘The Church and the Two Nations in Late Medieval Armagh’, in W. J. Sheils and Diana Wood (eds), The Churches, Ireland and the Irish, Studies in Church History 25 (1989). 4. The first volume of proceedings has been published as Robert Armstrong and Tadhg Ó hAnnracháin (eds), Insular Christianity: Alternative Models of the Church in Britain and Ireland c.1570–c.1700 (Manchester, 2013). 5. Kenneth Nicholls, ‘Celtic Contrasts: Ireland and Scotland’, History Ireland 7.3 (autumn 1999); Nicholls, ‘Worlds Apart? The Ellis Two-nation Theory on Late Medieval Ireland’, History Ireland 7.2 (summer 1999). 6. Patrick Corish, ‘The Cromwellian Regime, 1650–60’, in T. W. Moody, F. X. Martin and F. J. Byrne (eds), A New History of Ireland, III: Early Modern Ireland 1534–1691 (Oxford, 1976). 7. See e.g. Brian Mac Cuarta, Catholic Revival in the North of Ireland 1603–41 (Dublin, 2007); for Scotland see Jane Dawson, ‘Calvinism and the Gaidhealtachd in Scotland’, in Andrew Pettegree, Alastair Duke and Gillian Lewis (eds), Calvinism in Europe 1540–1620 (Cambridge, 1994). 8. Note for instance John Roche’s rather patronizing description of the Gaelic bishops, all of whom were seminary-trained on the Continent, who were appointed to Gaelic sees during the 1620s, in P. -

The Poetic Brehon Lawyers of Early Sixteenth Century Ireland for The

THE POETIC BREHON LAWYERS The Poetic Brehon Lawyers Of Early Sixteenth Century Ireland For the year 1529 the Annals of Loch Cé1 record the deaths of four Irish brehons, or traditional lawyers. Three of them are said to be learned in poetry as well. The longest entry concerns An Cosnamhach Mac Aodhagáin, or MacEgan, the most eminent man in the lands of the Gaeidhel in Irish customary law [fénechas], and in poetry [filidhecht], with secular jurisprudence [breithemnus tuaithi]. (This latter phrase is understood by the editor to refer to a knowledge of Roman civil law, certainly a possible interpretation.) These poetic lawyers of 1529 are by no means unusual. The two most influential families of hereditary Irish lawyers during the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, the MacEgans of Connacht and Tipperary and the MacClancy (Mac Fhlannchadha) judges to the OBriens in Co. Clare, each produced experts in poetry and general Irish literature, generation after generation,2 and the MacEgans also cultivated music.3 We are told the ideal ollamh or master of the legal profession should be expert in every art,4 that is in all branches of vernacular Irish learning: customary law, bardic poetry, music, medicine, 1 Edited W.M. Hennessy, 2 vols, London 1871, reprinted Dublin 1939 [A.L.C.], ii, pp. 268–71; see also Annals of the kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters ed. J. ODonovan, 7 vols, Dublin 1851 [A.F.M.], v, pp. 1396-7. 2 Annála Uladh: Annals of Ulster ed. W.M. Hennessy and B. MacCarthy , 4 vols, Dublin 1887-1901 [A.U.], ii, pp. -

Forms of Patriotism of the Early Modern Irish Nobility

Вестник СПбГУ. История. 2017. Т. 62. Вып. 1 F. E. Levin FORMS OF PATRIOTISM OF THE EARLY MODERN IRISH NOBILITY The article is dedicated to the phenomenon of patriotism of the Irish nobility in the reign of early Stuarts, when specific loyalist consciousness of distinction within the composite British state of the Roman Catholic subjects, both of Old English and Gaelic descent, was formed. The author suggests a term ‘patrimonial patriotism’, which combines both medieval and new aspects, for describing patriotism in early modern Ireland. He compares and contrasts different forms of patriotism in Stuart Ireland: Old English traditional allegiances, Irish patriotism of both Old English and Gaels and also a distinct Gaelic dimension of patriotism. The Old English patriotism is rather to be considered seigneurial loyalty since their constitutional, territorial and historical legitimacy was based on their motherland in England. Patrimonial patriotism of Old English and Gaels was characterized by loyalty to Catholicism and the Stuart’s dynasty. The most complete form of Irish patriotism supposed appropriation of the Gaelic past and cultural practices and at the same time acknowledging the legitimacy of the English invasion. In the Gaelic dimension of patriotism loyalty to Stuarts was combined with non-recognition of the legitimacy of the English invasion and disappointment with the collapse of the traditional Gaelic order. The author highlights that common features of these forms of patriotism were, in part, their politicized, monarchical and Catholic nature, their feeling of distinction and non-Englishness and their non-modern character. He also points out that the case of Ireland shows patriotism is not restricted to only ethnic and territorial aspects, but is always mixed with other elements.