Ÿþm Icrosoft W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded on 2017-02-12T14:01:46Z DP ,Too 0 OO'dtj

Title Edmund Burke and the heritage of oral culture Author(s) O'Donnell, Katherine Publication date 2000 Original citation O'Donnell, K. 2000. Edmund Burke and the heritage of oral culture. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Link to publisher's http://library.ucc.ie/record=b1306492~S0 version Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2000, Katherine O'Donnell http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Embargo information No embargo required Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/1611 from Downloaded on 2017-02-12T14:01:46Z DP ,too 0 OO'DtJ Edmund Burke & the Heritage of Oral Culture Submitted by: Katherine O'Donnell Supervisor: Professor Colbert Kearney External Examiner: Professor Seamus Deane English Department Arts Faculty University College Cork National University of Ireland January 2000 I gcuimhne: Thomas O'Caliaghan of Castletownroche, North Cork & Sean 6 D6naill as Iniskea Theas, Maigh Eo Thuaidh Table of Contents Introduction - "To love the little Platoon" 1 Burke in Nagle Country 13 "Image of a Relation in Blood"- Parliament na mBan &Burke's Jacobite Politics 32 Burke &the School of Irish Oratory 56 Cuirteanna Eigse & Literary Clubs n "I Must Retum to my Indian Vomit" - Caoineadh's Cainte - Lament and Recrimination 90 "Homage of a Nation" - Burke and the Aisling 126 Bibliography 152 Introduction· ''To love the little Platoon" Introduction - "To love the little Platoon" To be attached to the subdivision, to love the little platoon we belong to in society, is the first principle (the germ as it were) ofpublic affections. -

De Vesci Papers

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 89 DE VESCI PAPERS (Accession No. 5344) Papers relating to the family and landed estates of the Viscounts de Vesci. Compiled by A.P.W. Malcomson; with additional listings prepared by Niall Keogh CONTENTS INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...........................................................6 I TITLE DEEDS, C.1533-1835 .........................................................................................19 I.i Muschamp estate, County Laois, 1552-1800 ............................................................................................19 I.ii Muschamp estates (excluding County Laois), 1584-1716........................................................................20 I.iii Primate Boyle’s estates, 1666-1835.......................................................................................................21 I.iv Miscellaneous title deeds to other properties c.1533-c. 1810..............................................................22 II WILLS, SETTLEMENTS, LEASES, MORTGAGES AND MISCELLANEOUS DEEDS, 1600-1984 ..................................................................................................................23 II.i Wills and succession duty papers, 1600-1911 ......................................................................................23 II.ii Settlements, mortgages and miscellaneous deeds, 1658-1984 ............................................................27 III LEASES, 1608-1982 ........................................................................................................35 -

Post Primary Schools Within a 160KM Radius of Maynooth University

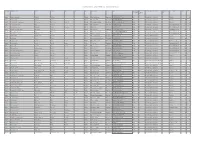

Post Primary Schools within a 160KM radius of Maynooth University Roll Number Official School Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Address 4 County Principal Name Phone Email School Gender Pupil Irish Classification - Post Primary Fee Paying School Ethos/Religion FEMALE MALE - Post Primary Attendance (Y/N) Type 61120E St Mary's Academy CBS Station Rd Carlow CARLOW MR. PAUL FIELDS 0599142419 [email protected] Boys Day No subjects taught through Irish N CATHOLIC 583 61130H St Mary's Knockbeg College Knockbeg Co. Carlow CARLOW MR. MICHAEL CAREW 0599142127 [email protected] Boys Day No subjects taught through Irish N CATHOLIC 411 61140K St. Leo's College Dublin Road Carlow CARLOW MISS CLARE RYAN 0599143660 [email protected] Girls Day No subjects taught through Irish N CATHOLIC 966 61141M Presentation College Askea Carlow Co. Carlow CARLOW MR. RAYMOND MURRAY 0599143927 [email protected] Mixed Day No subjects taught through Irish N CATHOLIC 370 354 61150N Presentation / De La Salle College Royal Oak Road Muine Bheag Co. Carlow CARLOW MR. GERARD WATCHORN 0599721860 [email protected] Mixed Day No subjects taught through Irish N CATHOLIC 283 313 70400L Borris Vocational School Borris Co Carlow CARLOW Mr John O'Sullivan 0599773155 [email protected] Mixed Day No subjects taught through Irish N INTER DENOMINATIONAL 237 269 70410O Coláiste Eoin Hacketstown Co Carlow CARLOW Pauline Egan 0596471198 [email protected] Mixed Day No subjects taught through Irish N INTER DENOMINATIONAL 111 122 70420R Carlow Vocational -

Research Guide for Archival Sources of Smock Alley Theatre, Dublin

Research Guide for Archival Sources of Smock Alley theatre, Dublin. October 2009 This research guide is intended to provide an accessible insight into the historical, theatrical and archival legacy of Smock Alley theatre, Dublin. It is designed as an aid for all readers and researchers who have an interest in theatre history and particularly those wishing to immerse themselves in the considerable theatrical legacy of Smock Alley theatre and it’s array of actors, actresses, directors, designers, its many scandals and stories, of what was and is a unique theatrical venue in the fulcrum of Dublin’s cultural heart. Founded in 1662 by John Ogilby, Smock Alley theatre and stage was home to many of the most famous and talented actors, writers and directors ever to work and produce in Ireland, England, Scotland and Wales, throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth century. Celebrated players included Peg Woffington, David Garrick, Colley Cibber, Spranger Barry and George Ann Bellamy. Renowned managers and designers such as John Ogilby, Thomas Sheridan, Louis De Val and Joseph Ashbury would help cement the place of Smock Alley theatre as a venue of immense theatrical quality where more than just a play was produced and performed but more of a captivating, wild and entertaining spectacle. The original playbills from seventeenth century productions at Smock Alley detail many and varied interval acts that often took place as often as between every act would feature singing, dancing, farce, tumbling, juggling and all manner of entertainment for the large public audience. Smock Alley was celebrated for its musical and operatic productions as well as its purely dramatic performances. -

VV-J 0 32-1450 M-Uww U V W a Chapter of Hitherto Unwritten

172 2008 PRE FA CE . The following H ist ory of a family numerous and I prosperous beyond recount, will, hope , prove acceptable no w to their descendants . These are to be found in all classes of society , and many have forgotten all about their forefathers and have not even a tradition remain i ing. Nay, members of this family who st ll live as county families in Ireland have become so culpably careless that a few generations is the limit of their d knowle ge . It will show the difficulty of the historian and n d o f genealogist, here at least whe it is state that George Lewis Jones , who was Bishop of this Diocese 1774— 1790 I not , could gather a particle of informa I tion but the meagre facts have stated . ! I PRE FACE . The transmission of physical conformation and facial expression , as well as that of moral qualities and defects , is an interesting study to the philosopher . In some u families you can trace for cent ries the same expression, featurmes and color, often the same height and very often li the sa e moral and intellectual qua ties . As a general u - rule, the feat res of this wide spread family , no matter i whether rich or poor, gifted or gnorant , are marked n by peculiar characteristics that, o ce seen and noted . N . cannot well be forgotten Captain Jones, R , M P I for Londonderry, whom knew when a boy, now Rear Admiral Sir Lewis Tobias Jones, the Rev . Thomas of I w J . -

Irish Literature, 1750–1900

Wright: Irish Literature 1750–1900 9781405145190_4_001 Page Proof page 131.7.2007 3:38pm Irish Literature, 1750–1900 Wright: Irish Literature 1750–1900 9781405145190_4_001 Page Proof page 231.7.2007 3:38pm Wright: Irish Literature 1750–1900 9781405145190_4_001 Page Proof page 331.7.2007 3:38pm Thomas Sheridan (1719–1788) Thomas Sheridan, probably born in Dublin but Humble Appeal also included a proposal for a possibly in Co. Cavan, was the son of another national theater in Dublin that would be publicly Thomas Sheridan (clergyman and author) and administered and ensure fair treatment of theater the godson of Jonathan Swift (a close friend of workers. the family). He may have been a descendant of As a dramatist, Sheridan mostly adapted other Denis Sheridan (c.1610–83), a native Irish authors’ works, as was common in his day; he speaker who assisted in the translation of the adapted, for instance, Coriolanus (1755) from Old Testament into Irish as part of Bishop texts by English authors William Shakespeare Bedell’s efforts to make the Church of Ireland and James Thomson. His enduringly popular accessible to Irish speakers. The younger Thomas farce The Brave Irishman: Or, Captain O’Blunder Sheridan worked primarily in the theater, as was published and staged throughout the second actor, manager, playwright, and author of var- half of the eighteenth century and compactly ious tracts related to theater reform, but also abbreviated in three double-columned pages published on other subjects, including British for the Cabinet of Irish Literature a century Education: Or the Source of Disorders in Great later. -

Thomas Sheridan: Pioneer in British Speech Technology

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 67-2513 PATTERSON, Robert Ellis, 1907- THOMAS SHERIDAN: PIONEER IN BRITISH SPEECH TECHNOLOGY. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1966 %)eech University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan 0 Copyright by Robert Ellis Patterson 19671 THOMAS SHERIDAN; PIONEER IN BRITISH SPEECH TECHNOLOGY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert Ellis Patterson, A.B., B.S., M.A. * A *. ft ft ft * The Ohio State University 1966 Approved by à J ï Adviser Department of Speech PREFACE But when he [the author] adds, that he is. the first who ever laid open the principles upon which our language is founded, and the rules by which it is regulated, he hopes the claim he has laid in to the office he has undertaken, will not be considered either vain or pre sumptuous . Thomas Sheridan Dictionary, Preface, p. xi. Probably everyone would like to discover, or be the first to do something. It is only a vicarious thrill that this author has. This is a study in the evaluation and comparison of one who pioneered. Thomas Sheridan may not have thought of himself as having pioneered in three aspects of the speaking situation. He may not have thought of himself as having pioneered in three phases of British speech technology. But this is. the way the present author looks upon one man th a t h isto ry has overlooked. Evaluation is made easy by the passing of time. -

Jonathan Swift's Hoax of 1722 Upon Ebenezor Elliston

JONATHAN SWIFT'S HOAX OF 1722 UPON EBENEZOR ELLISTON BY GEORGE P. MAYHEW, M.A., Ph.D. ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH AT THE CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY I HILE examining some Dublin newspapers from the Wperiod 1719-22 I lately came upon additional information which may be useful to readers of Dr. Daniel L. McCue's recent scholarly account of " A Newly Discovered Broadsheet of Swift's Last Speech and Dying Words of Ebenezor Elliston '. * In addition to Swift's parody, the three other sources of information about Ebenezor Elliston, the victim of Swift's hoax of 1722, have hitherto been : The Last Farewell of Ebenezor Elliston To This Transitory World, an autobiographical Dublin broadsheet of 1722 preserved now in Archbishop Marsh's Library, Dublin, and printed by Professor Herbert Davis as an Appendix (pp. 363-7) to volume IX of his edition of Swift's Prose Writings ; 2 George Faulkner's headnote to Swift's broadsheet as published in the 1735 Dublin edition of Swift's Works ;3 and a note appended to the same piece by Thomas Sheridan, the younger, in his 1784 edition of Swift's Works.* Both of these last two pieces of in formation were accepted without question and have been merely paraphrased or summarized by such later editors of Swift's Works as John Nichols, who mistakenly attributed Sheridan's note to Faulkner, by Sir Walter Scott, and by Temple Scott.5 1 Harvard Library Bulletin, xiii (Autumn, 1959), 362-8. Hereafter referred to within the text by page number alone. 2 14 vols., Oxford, 1939- (in progress). -

Thomas Sheridan and the Evil Ends of Writing

Conrad Brunstr?m Thomas Sheridan and the Evil Ends ofWriting Two new biographies of the great dramatist and parliamentarian Richard Brins ley Sheridan have provoked a renewal of interest in the whole Sheridan dynasty.1 InA TraitorysKiss (1997), Fintan O' Toole occasionally discusses Thomas Sheri dan's educational obsessions, but his sympathy for the son leads him to focus on the lackluster parenting skills of the father. In her life of Sheridan, Linda Kelly remarks of the dramatist's father that although "Thomas Sheridan's achieve ments had never been fully recognized in his lifetime. [...] Thomas Sheridan own on to con has his claims posterity."2 These claims have yet receive serious sideration, even by scholars of the eighteenth century. Thomas Sheridan (1719-1788), son of the poet, father of the dramatist, hus as band of the novelist?as well actor, stage manager, educational reformer, and public lecturer?passionately believed that speech was a higher and truer form of communication than writing, and understandably so, because he was the most influential elocutionist of his day. In his own lifetime, however, Thomas Sheridan was perhaps best known as one of the greatest tragic actors of the mid eighteenth century. Charles Churchill's poem The Rosciad, a best-selling survey of contemporary (1760) acting talent, regards Sheridan as a flawed but fasci nating touchstone of dramatic and rhetorical taste. But, spite of all defects, his glories rise; And Art, by Judgement form'd, with Nature vies. Where he falls short 'tis Nature's fault alone; Where he succeeds, the Merit's all his own.3 Sheridan is the penultimate player in Churchill's catalogue. -

Jonathan Swift: Journal to Stella: Letters to Esther Johnson and Rebecca Dingley, 1710–1713 Edited by Abigail Williams Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-84166-5 - Jonathan Swift: Journal to Stella: Letters to Esther Johnson and Rebecca Dingley, 1710–1713 Edited by Abigail Williams Frontmatter More information the cambridge edition of the works of jonathan swift © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-84166-5 - Jonathan Swift: Journal to Stella: Letters to Esther Johnson and Rebecca Dingley, 1710–1713 Edited by Abigail Williams Frontmatter More information the cambridge edition of the works of jonathan swift General Editors Claude Rawson Yale University Ian Higgins Australian National University David Womersley University of Oxford Ian Gadd Bath Spa University Textual Adviser James McLaverty Keele University AHRC Research Fellows Paddy Bullard University of Oxford Adam Rounce Keele University Daniel Cook Keele University Advisory Board John Brewer Sean Connolly Seamus Deane Denis Donoghue Howard Erskine-Hill Mark Goldie Phillip Harth Paul Langford James E. May Ronald Paulson J. G. A. Pocock Pat Rogers G. Thomas Tanselle David L. Vander Meulen © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-84166-5 - Jonathan Swift: Journal to Stella: Letters to Esther Johnson and Rebecca Dingley, 1710–1713 Edited by Abigail Williams Frontmatter More information the cambridge edition of the works of jonathan swift 1. A Tale of a Tub and Other Works 2. Parodies, Hoaxes, Mock Treatises: Polite Conversation, Directions to Servants and Other Works 3.–6. Poems 7. English Political Writings 1701–1711: The Examiner and Other Works 8. English Political Writings 1711–1714: The Conduct of the Allies and Other Works 9 Journal to Stella: Letters to Esther Johnson and Rebecca Dingley 1710–1713 10. -

Complete Volume

THE PARISH REGISTERS OF CHRIST CHURCH, DELGANY VOLUME 3 BAPTISMS 1819-1840 MARRIAGES 1819-1840 BURIALS 1819-1840 TRANSCRIBED AND INDEXED Diocese of Glendalough County of Wicklow The Anglican Record Project The Anglican Record Project - the transcription and indexing of Registers and other documents/sources of genealogical interest of Anglican Parishes in the British Isles. Twenty-third in the Register Series. CHURCH (County, Diocese ) BAPTISMS MARRIAGES BURIALS Longcross, Christ Church 1847-1990 1847-1990 1847-1990 (Surrey, Guildford ) [Aug 91] Kilgarvan, St Peter's Church 1811-1850 1812-1947 1819-1850 (Kerry, Ardfert & Aghadoe )[Mar 92] 1878-1960 Fermoy Garrison Church 1920-1922 (Cork, Cloyne ) [Jul 93] Barragh, St Paul's Church 1799-1805 1799-1805 1799-1805 (Carlow, Ferns ) [Apr 94] 1831-1879 1830-1844 1838-1878 Newtownbarry, St Mary's Church 1799-1903 1799-1903 1799-1903 (Wexford, Ferns ) [Oct 97] Affpuddle, St Laurence's Church 1728-1850 1731-1850 1722-1850 (Dorset, Salisbury ) [Nov 97] Barragh, St Paul's Church 1845-1903 (Carlow, Ferns ) [Jul 95] Kenmare, St Patrick's Church 1819-1950 (Kerry, Ardfert & Aghadoe )[Sep 95] Clonegal, St Fiaac's Church 1792-1831 1792-1831 1792-1831 (Carlow/Wexford/Wicklow, Ferns ) [May 96] Clonegal, St Fiaac's Church 1831-1903 (Carlow/Wexford/Wicklow, Ferns ) [Jul 96] Kilsaran, St Mary’s Church 1818-1840 1818-1844 1818-1900 (Louth, Armagh ) [Sep 96] Clonegal, St Fiaac's Church 1831-1906 (Carlow/Wexford/Wicklow, Ferns ) [Feb 97] (Continued on inside back cover.) JUBILATE DEO (Psalm 100) O be joyful in the Lord, all ye lands: serve the Lord with gladness, and come before his presence with a song. -

Collection of Jonathan Swift Materials: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8zk5n35 No online items Collection of Jonathan Swift materials: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Diann Benti. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Rare Books Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2015 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Collection of Jonathan Swift mssHM 1599, etc. mssHM 1599, mssHM 14326-14390, mssHM 1 materials: Finding Aid 22660; mssHM 24016-HM 24018; mssHM 27942-HM 27943; mssHM 31303; mssHM 51865 Overview of the Collection Title: Collection of Jonathan Swift materials Dates (inclusive): 1698-1881 Bulk dates: 1720-1745 Collection Number: mssHM 1599, etc. Additional Collection Numbers: mssHM 1599, mssHM 14326-14390, mssHM 22660; mssHM 24016-HM 24018; mssHM 27942-HM 27943; mssHM 31303; mssHM 51865 Creator: Swift, Jonathan, 1667-1745. Extent: 74 items in 1 box and 1 volume Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Rare Books Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains 74 pieces related to Anglo-Irish writer, satirist and cleric Jonathan Swift (1667-1745), chiefly representing his later life in Ireland from the 1720s to the late 1730s. Documents include manuscripts in Swift's hand, or contemporary copies, as well as letters and verse to and from Swift and his friends, and documents endorsed by Swift or once in his possession. Language: English. Note: Finding aid last updated on November 20, 2015.