Thomas Sheridan and the Evil Ends of Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Gothic Fiction

THE ‘If the Gothic emerges in the shadows cast by modernity and its pasts, Ireland proved EME an unhappy haunting ground for the new genre. In this incisive study, Jarlath Killeen shows how the struggle of the Anglican establishment between competing myths of civility and barbarism in eighteenth-century Ireland defined itself repeatedly in terms R The Emergence of of the excesses of Gothic form.’ GENCE Luke Gibbons, National University of Ireland (Maynooth), author of Gaelic Gothic ‘A work of passion and precision which explains why and how Ireland has been not only a background site but also a major imaginative source of Gothic writing. IRISH GOTHIC Jarlath Killeen moves well beyond narrowly political readings of Irish Gothic by OF IRISH GOTHIC using the form as a way of narrating the history of the Anglican faith in Ireland. He reintroduces many forgotten old books into the debate, thereby making some of the more familiar texts seem suddenly strange and definitely troubling. With FICTION his characteristic blend of intellectual audacity and scholarly rigour, he reminds us that each text from previous centuries was written at the mercy of its immediate moment as a crucial intervention in a developing debate – and by this brilliant HIST ORY, O RIGI NS,THE ORIES historicising of the material he indicates a way forward for Gothic amidst the ruins of post-Tiger Ireland.’ Declan Kiberd, University of Notre Dame Provides a new account of the emergence of Irish Gothic fiction in the mid-eighteenth century FI This new study provides a robustly theorised and thoroughly historicised account of CTI the beginnings of Irish Gothic fiction, maps the theoretical terrain covered by other critics, and puts forward a new history of the emergence of the genre in Ireland. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title "Furbish'd Remnants": Theatrical Adaptation and the Orient, 1660-1815 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0998z0zz Author Del Balzo, Angelina Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “Furbish’d Remnants”: Theatrical Adaptation and the Orient, 1660-1815 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Angelina Marie Del Balzo 2019 Ó Copyright by Angelina Marie Del Balzo 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “Furbish’d Remnants”: Theatrical Adaptation and the Orient, 1660-1815 by Angelina Marie Del Balzo Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Felicity A. Nussbaum, Chair Furbish’d Remnants argues that eighteenth-century theatrical adaptations set in the Orient destabilize categories of difference, introducing Oriental characters as subjects of sympathy while at the same time defamiliarizing the people and space of London. Applying contemporary theories of emotion, I contend that in eighteenth-century theater, the actor and the character become distinct subjects for the affective transfer of sympathy, increasing the emotional potential of performance beyond the narrative onstage. Adaptation as a form heightens this alienation effect, by drawing attention to narrative’s properties as an artistic construction. A paradox at the heart of eighteenth-century theater is that while the term “adaptation” did not have a specific literary or theatrical definition until near the end of the period, in practice adaptations and translations proliferated on the English stage. -

Downloaded on 2017-02-12T14:01:46Z DP ,Too 0 OO'dtj

Title Edmund Burke and the heritage of oral culture Author(s) O'Donnell, Katherine Publication date 2000 Original citation O'Donnell, K. 2000. Edmund Burke and the heritage of oral culture. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Link to publisher's http://library.ucc.ie/record=b1306492~S0 version Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2000, Katherine O'Donnell http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Embargo information No embargo required Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/1611 from Downloaded on 2017-02-12T14:01:46Z DP ,too 0 OO'DtJ Edmund Burke & the Heritage of Oral Culture Submitted by: Katherine O'Donnell Supervisor: Professor Colbert Kearney External Examiner: Professor Seamus Deane English Department Arts Faculty University College Cork National University of Ireland January 2000 I gcuimhne: Thomas O'Caliaghan of Castletownroche, North Cork & Sean 6 D6naill as Iniskea Theas, Maigh Eo Thuaidh Table of Contents Introduction - "To love the little Platoon" 1 Burke in Nagle Country 13 "Image of a Relation in Blood"- Parliament na mBan &Burke's Jacobite Politics 32 Burke &the School of Irish Oratory 56 Cuirteanna Eigse & Literary Clubs n "I Must Retum to my Indian Vomit" - Caoineadh's Cainte - Lament and Recrimination 90 "Homage of a Nation" - Burke and the Aisling 126 Bibliography 152 Introduction· ''To love the little Platoon" Introduction - "To love the little Platoon" To be attached to the subdivision, to love the little platoon we belong to in society, is the first principle (the germ as it were) ofpublic affections. -

An Examination of the Theories and Methodologies of John Walker (1732- 1807) with Emphasis Upon Gesturing

This dissertation has been 64—7006 microfilmed exactly as received DODEZ, M. Leon, 1934- AN EXAMINATION OF THE THEORIES AND METHODOLOGIES OF JOHN WALKER (1732- 1807) WITH EMPHASIS UPON GESTURING. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1963 Speech—Theater University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan AN EXAMINATION OP THE THEORIES AND METHODOLOGIES OP JOHN WALKER (1732-1807) WITH EMPHASIS UPON GESTURING DISSERTATION Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By M. Leon Dodez, B.Sc., M.A ****** The Ohio State University 1963 Approved by Department of Speech ACKNOWLEDGMENT I wish to express my gratitude to Dr. George Lewis for his assistance In helping to shape my background, to Dr. Franklin Knower for guiding me to focus, and to Dr. Keith Brooks, my adviser, for his cooperation, patience, encouragement, leadership, and friendship. All three have given much valued time, encouragement and knowledge. ii CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................... 1 Chapter I. INTRODUCTION............................... 1 II, BIOGRAPHY................................... 9 III. THE PUBLICATIONS OP JOHN WALKE R............. 27 IV. JOHN WALKER, ORTHOEPIST AND LEXIGRAPHER .... 43 V. NATURALISM AND MECHANICALISM............... 59 VI. THEORY AND METHODOLOGY..................... 80 VII^ POSTURE AND P A S S I O N S ......................... 110 VIII. APPLICATION AND PROJECTIONS OP JOHN WALKER'S THEORIES AND METHODOLOGIES......... 142 The Growth of Elocution......................143 L a n g u a g e ................................... 148 P u r p o s e s ................................... 150 H u m o r ....................................... 154 The Disciplines of Oral Reading and Public Speaking ......................... 156 Historical Analysis ....................... 159 The Pa u s e .................................. -

De Vesci Papers

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 89 DE VESCI PAPERS (Accession No. 5344) Papers relating to the family and landed estates of the Viscounts de Vesci. Compiled by A.P.W. Malcomson; with additional listings prepared by Niall Keogh CONTENTS INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...........................................................6 I TITLE DEEDS, C.1533-1835 .........................................................................................19 I.i Muschamp estate, County Laois, 1552-1800 ............................................................................................19 I.ii Muschamp estates (excluding County Laois), 1584-1716........................................................................20 I.iii Primate Boyle’s estates, 1666-1835.......................................................................................................21 I.iv Miscellaneous title deeds to other properties c.1533-c. 1810..............................................................22 II WILLS, SETTLEMENTS, LEASES, MORTGAGES AND MISCELLANEOUS DEEDS, 1600-1984 ..................................................................................................................23 II.i Wills and succession duty papers, 1600-1911 ......................................................................................23 II.ii Settlements, mortgages and miscellaneous deeds, 1658-1984 ............................................................27 III LEASES, 1608-1982 ........................................................................................................35 -

Post Primary Schools Within a 160KM Radius of Maynooth University

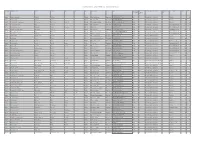

Post Primary Schools within a 160KM radius of Maynooth University Roll Number Official School Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Address 4 County Principal Name Phone Email School Gender Pupil Irish Classification - Post Primary Fee Paying School Ethos/Religion FEMALE MALE - Post Primary Attendance (Y/N) Type 61120E St Mary's Academy CBS Station Rd Carlow CARLOW MR. PAUL FIELDS 0599142419 [email protected] Boys Day No subjects taught through Irish N CATHOLIC 583 61130H St Mary's Knockbeg College Knockbeg Co. Carlow CARLOW MR. MICHAEL CAREW 0599142127 [email protected] Boys Day No subjects taught through Irish N CATHOLIC 411 61140K St. Leo's College Dublin Road Carlow CARLOW MISS CLARE RYAN 0599143660 [email protected] Girls Day No subjects taught through Irish N CATHOLIC 966 61141M Presentation College Askea Carlow Co. Carlow CARLOW MR. RAYMOND MURRAY 0599143927 [email protected] Mixed Day No subjects taught through Irish N CATHOLIC 370 354 61150N Presentation / De La Salle College Royal Oak Road Muine Bheag Co. Carlow CARLOW MR. GERARD WATCHORN 0599721860 [email protected] Mixed Day No subjects taught through Irish N CATHOLIC 283 313 70400L Borris Vocational School Borris Co Carlow CARLOW Mr John O'Sullivan 0599773155 [email protected] Mixed Day No subjects taught through Irish N INTER DENOMINATIONAL 237 269 70410O Coláiste Eoin Hacketstown Co Carlow CARLOW Pauline Egan 0596471198 [email protected] Mixed Day No subjects taught through Irish N INTER DENOMINATIONAL 111 122 70420R Carlow Vocational -

Research Guide for Archival Sources of Smock Alley Theatre, Dublin

Research Guide for Archival Sources of Smock Alley theatre, Dublin. October 2009 This research guide is intended to provide an accessible insight into the historical, theatrical and archival legacy of Smock Alley theatre, Dublin. It is designed as an aid for all readers and researchers who have an interest in theatre history and particularly those wishing to immerse themselves in the considerable theatrical legacy of Smock Alley theatre and it’s array of actors, actresses, directors, designers, its many scandals and stories, of what was and is a unique theatrical venue in the fulcrum of Dublin’s cultural heart. Founded in 1662 by John Ogilby, Smock Alley theatre and stage was home to many of the most famous and talented actors, writers and directors ever to work and produce in Ireland, England, Scotland and Wales, throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth century. Celebrated players included Peg Woffington, David Garrick, Colley Cibber, Spranger Barry and George Ann Bellamy. Renowned managers and designers such as John Ogilby, Thomas Sheridan, Louis De Val and Joseph Ashbury would help cement the place of Smock Alley theatre as a venue of immense theatrical quality where more than just a play was produced and performed but more of a captivating, wild and entertaining spectacle. The original playbills from seventeenth century productions at Smock Alley detail many and varied interval acts that often took place as often as between every act would feature singing, dancing, farce, tumbling, juggling and all manner of entertainment for the large public audience. Smock Alley was celebrated for its musical and operatic productions as well as its purely dramatic performances. -

Die Wörterbücher Von Johannes Ebers Studien Zur Frühen Englisch-Deutschen Lexikografie

Die Wörterbücher von Johannes Ebers Studien zur frühen englisch-deutschen Lexikografie Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät I der Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg Vorgelegt von Derek Lewis aus Exeter Würzburg 2013 Erstgutachter: Professor Dr. Werner Wegstein Zweitgutachter: Professor Dr. Norbert Wolf Tag des Kolloquiums: 31.1.2011 DANK Mein Dank gilt allen, die zum Zustandekommen dieser Arbeit beigetragen haben. Insbesondere danke ich - Prof. Dr. Werner Wegstein von der Universität Würzburg für seine Anregung zu diesem Projekt und für seine kompetente Beratung und Betreuung, - meiner Frau für ihre Geduld und für ihre moralische und praktische Unterstützung, - den Kollegen der Bibliothek in Exeter (Devon and Exeter Institution Library), die mir die Originalexemplare der Wörterbücher von Johannes Ebers zur Verfügung gestellt haben. Inhalt Kapitel 1: Einleitung zur Entwicklung der deutsch-englischen Lexikografie .... 9 1.1 Die Anfänge der deutsch-englischen Lexikografie ............................ 9 1.2 Mehrsprachige Wörterbücher 1500 - ca. 1600 ............................... 10 1.3 Zweisprachige Wörterbücher 1550 - 1700 ...................................... 13 1.4 Entwicklungen im 18. Jahrhundert .................................................. 15 1.4.1 Der politische Hintergrund .............................................................. 15 1.4.2 Der Kulturtransfer zwischen England und Deutschland .................. 17 1.4.3 Übersetzungen als Träger des Kulturtransfers .............................. -

VV-J 0 32-1450 M-Uww U V W a Chapter of Hitherto Unwritten

172 2008 PRE FA CE . The following H ist ory of a family numerous and I prosperous beyond recount, will, hope , prove acceptable no w to their descendants . These are to be found in all classes of society , and many have forgotten all about their forefathers and have not even a tradition remain i ing. Nay, members of this family who st ll live as county families in Ireland have become so culpably careless that a few generations is the limit of their d knowle ge . It will show the difficulty of the historian and n d o f genealogist, here at least whe it is state that George Lewis Jones , who was Bishop of this Diocese 1774— 1790 I not , could gather a particle of informa I tion but the meagre facts have stated . ! I PRE FACE . The transmission of physical conformation and facial expression , as well as that of moral qualities and defects , is an interesting study to the philosopher . In some u families you can trace for cent ries the same expression, featurmes and color, often the same height and very often li the sa e moral and intellectual qua ties . As a general u - rule, the feat res of this wide spread family , no matter i whether rich or poor, gifted or gnorant , are marked n by peculiar characteristics that, o ce seen and noted . N . cannot well be forgotten Captain Jones, R , M P I for Londonderry, whom knew when a boy, now Rear Admiral Sir Lewis Tobias Jones, the Rev . Thomas of I w J . -

Civility, Patriotism and Performance: Cato and the Irish History Play

Ireland, Enlightenment and the English Stage, 1740-1820 7 Civility, patriotism and performance: Cato and the Irish history play David O’Shaughnessy Recent scholarship has underscored history writing as central to the culture of the eighteenth century and as a key mode of Enlightenment thought and practice in both Britain and Ireland.1 British elites, conscious of their own historiographical failings, looked uneasily on the French exemplar national histories which sparked a patriotic urging to match their Continental competitors.2 Writ properly, it was suggested, history could also lead to a more rational patriotic attachment to one’s own country, one enriched by a recognition of other nations in the spirit of Enlightenment.3 The proper framing and writing of national history (understood in the main as that which adhered to rigorous neoclassical values) also conveyed a country’s teleological progressiveness, its emergence from barbarity towards modernity, civilization and associated institutional norms. The form and content of a well written national history—encompassing inter alia a decorous tone, idealized characters, moral didacticism—mirrored each other, allowing a reader to assess their own civility as well as that of the country and its people in question. Enlightenment is a term with a myriad of My sincere thanks to Emily Anderson and David Taylor for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this essay. This chapter has received funding from the European Union’s 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklowdowska-Curie grant agreement No 745896. 1 Noelle Gallagher, Historical Literatures: Writing about the Past in England, 1660–1740 (Manchester University Press, 2012); Ruth Mack, Literary Historicity: Literature and Historical Experience in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Stanford University Press, 2009); and, Karen O’Brien, Narratives of Enlightenment: Cosmopolitan History from Voltaire to Gibbon (Cambridge University Press, 1997). -

Irish Literature, 1750–1900

Wright: Irish Literature 1750–1900 9781405145190_4_001 Page Proof page 131.7.2007 3:38pm Irish Literature, 1750–1900 Wright: Irish Literature 1750–1900 9781405145190_4_001 Page Proof page 231.7.2007 3:38pm Wright: Irish Literature 1750–1900 9781405145190_4_001 Page Proof page 331.7.2007 3:38pm Thomas Sheridan (1719–1788) Thomas Sheridan, probably born in Dublin but Humble Appeal also included a proposal for a possibly in Co. Cavan, was the son of another national theater in Dublin that would be publicly Thomas Sheridan (clergyman and author) and administered and ensure fair treatment of theater the godson of Jonathan Swift (a close friend of workers. the family). He may have been a descendant of As a dramatist, Sheridan mostly adapted other Denis Sheridan (c.1610–83), a native Irish authors’ works, as was common in his day; he speaker who assisted in the translation of the adapted, for instance, Coriolanus (1755) from Old Testament into Irish as part of Bishop texts by English authors William Shakespeare Bedell’s efforts to make the Church of Ireland and James Thomson. His enduringly popular accessible to Irish speakers. The younger Thomas farce The Brave Irishman: Or, Captain O’Blunder Sheridan worked primarily in the theater, as was published and staged throughout the second actor, manager, playwright, and author of var- half of the eighteenth century and compactly ious tracts related to theater reform, but also abbreviated in three double-columned pages published on other subjects, including British for the Cabinet of Irish Literature a century Education: Or the Source of Disorders in Great later. -

Thomas Sheridan: Pioneer in British Speech Technology

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 67-2513 PATTERSON, Robert Ellis, 1907- THOMAS SHERIDAN: PIONEER IN BRITISH SPEECH TECHNOLOGY. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1966 %)eech University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan 0 Copyright by Robert Ellis Patterson 19671 THOMAS SHERIDAN; PIONEER IN BRITISH SPEECH TECHNOLOGY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert Ellis Patterson, A.B., B.S., M.A. * A *. ft ft ft * The Ohio State University 1966 Approved by à J ï Adviser Department of Speech PREFACE But when he [the author] adds, that he is. the first who ever laid open the principles upon which our language is founded, and the rules by which it is regulated, he hopes the claim he has laid in to the office he has undertaken, will not be considered either vain or pre sumptuous . Thomas Sheridan Dictionary, Preface, p. xi. Probably everyone would like to discover, or be the first to do something. It is only a vicarious thrill that this author has. This is a study in the evaluation and comparison of one who pioneered. Thomas Sheridan may not have thought of himself as having pioneered in three aspects of the speaking situation. He may not have thought of himself as having pioneered in three phases of British speech technology. But this is. the way the present author looks upon one man th a t h isto ry has overlooked. Evaluation is made easy by the passing of time.