Patterns of Temporal and Spatial Variability of Sponge Assemblages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taxonomy and Diversity of the Sponge Fauna from Walters Shoal, a Shallow Seamount in the Western Indian Ocean Region

Taxonomy and diversity of the sponge fauna from Walters Shoal, a shallow seamount in the Western Indian Ocean region By Robyn Pauline Payne A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Magister Scientiae in the Department of Biodiversity and Conservation Biology, University of the Western Cape. Supervisors: Dr Toufiek Samaai Prof. Mark J. Gibbons Dr Wayne K. Florence The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF. December 2015 Taxonomy and diversity of the sponge fauna from Walters Shoal, a shallow seamount in the Western Indian Ocean region Robyn Pauline Payne Keywords Indian Ocean Seamount Walters Shoal Sponges Taxonomy Systematics Diversity Biogeography ii Abstract Taxonomy and diversity of the sponge fauna from Walters Shoal, a shallow seamount in the Western Indian Ocean region R. P. Payne MSc Thesis, Department of Biodiversity and Conservation Biology, University of the Western Cape. Seamounts are poorly understood ubiquitous undersea features, with less than 4% sampled for scientific purposes globally. Consequently, the fauna associated with seamounts in the Indian Ocean remains largely unknown, with less than 300 species recorded. One such feature within this region is Walters Shoal, a shallow seamount located on the South Madagascar Ridge, which is situated approximately 400 nautical miles south of Madagascar and 600 nautical miles east of South Africa. Even though it penetrates the euphotic zone (summit is 15 m below the sea surface) and is protected by the Southern Indian Ocean Deep- Sea Fishers Association, there is a paucity of biodiversity and oceanographic data. -

Patterns in Marine Community Assemblages on Continental Margins: a Faunal and Floral Synthesis from Northern Western Australian Atolls

Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia, 94: 267–284, 2011 Patterns in marine community assemblages on continental margins: a faunal and floral synthesis from northern Western Australian atolls A Sampey 1 & J Fromont 2 1 Aquatic Zoology, Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, WA 6986 [email protected] 2 Aquatic Zoology, Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, WA 6986 [email protected] Manuscript received November 2010; accepted January 2011 Abstract Corals and fishes are the most visually apparent fauna on coral reefs and the most often monitored groups to detect change. In comparison, data on noncoral benthic invertebrates and marine plants is sparse. Whether patterns in diversity and distribution for other taxonomic groups align with those detected in corals and fishes is largely unknown. Four shelf-edge atolls in the Kimberley region of Western Australia were surveyed for marine plants, sponges, scleractinian corals, crustaceans, molluscs, echinoderms and fishes in 2006, with a consequent 1521 species reported. Here, we provide the first community level assessment of the biodiversity of these atolls based on these taxonomic groups. Four habitats were surveyed and each was found to have a characteristic community assemblage. Different species assemblages were found among atolls and within each habitat, particularly in the lagoon and reef flat environments. In some habitats we found the common taxa groups (fishes and corals) provide adequate information for community assemblages, but in other cases, for example in the intertidal reef flats, these commonly targeted groups are far less useful in reflecting overall community patterns. -

Diversity of Norwegian Sea Slugs (Nudibranchia): New Species to Norwegian Coastal Waters and New Data on Distribution of Rare Species

Fauna norvegica 2013 Vol. 32: 45-52. ISSN: 1502-4873 Diversity of Norwegian sea slugs (Nudibranchia): new species to Norwegian coastal waters and new data on distribution of rare species Jussi Evertsen1 and Torkild Bakken1 Evertsen J, Bakken T. 2013. Diversity of Norwegian sea slugs (Nudibranchia): new species to Norwegian coastal waters and new data on distribution of rare species. Fauna norvegica 32: 45-52. A total of 5 nudibranch species are reported from the Norwegian coast for the first time (Doridoxa ingolfiana, Goniodoris castanea, Onchidoris sparsa, Eubranchus rupium and Proctonotus mucro- niferus). In addition 10 species that can be considered rare in Norwegian waters are presented with new information (Lophodoris danielsseni, Onchidoris depressa, Palio nothus, Tritonia griegi, Tritonia lineata, Hero formosa, Janolus cristatus, Cumanotus beaumonti, Berghia norvegica and Calma glau- coides), in some cases with considerable changes to their distribution. These new results present an update to our previous extensive investigation of the nudibranch fauna of the Norwegian coast from 2005, which now totals 87 species. An increase in several new species to the Norwegian fauna and new records of rare species, some with considerable updates, in relatively few years results mainly from sampling effort and contributions by specialists on samples from poorly sampled areas. doi: 10.5324/fn.v31i0.1576. Received: 2012-12-02. Accepted: 2012-12-20. Published on paper and online: 2013-02-13. Keywords: Nudibranchia, Gastropoda, taxonomy, biogeography 1. Museum of Natural History and Archaeology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway Corresponding author: Jussi Evertsen E-mail: [email protected] IntRODUCTION the main aims. -

A Soft Spot for Chemistry–Current Taxonomic and Evolutionary Implications of Sponge Secondary Metabolite Distribution

marine drugs Review A Soft Spot for Chemistry–Current Taxonomic and Evolutionary Implications of Sponge Secondary Metabolite Distribution Adrian Galitz 1 , Yoichi Nakao 2 , Peter J. Schupp 3,4 , Gert Wörheide 1,5,6 and Dirk Erpenbeck 1,5,* 1 Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Palaeontology & Geobiology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, 80333 Munich, Germany; [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (G.W.) 2 Graduate School of Advanced Science and Engineering, Waseda University, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 169-8555, Japan; [email protected] 3 Institute for Chemistry and Biology of the Marine Environment (ICBM), Carl-von-Ossietzky University Oldenburg, 26111 Wilhelmshaven, Germany; [email protected] 4 Helmholtz Institute for Functional Marine Biodiversity, University of Oldenburg (HIFMB), 26129 Oldenburg, Germany 5 GeoBio-Center, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, 80333 Munich, Germany 6 SNSB-Bavarian State Collection of Palaeontology and Geology, 80333 Munich, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Marine sponges are the most prolific marine sources for discovery of novel bioactive compounds. Sponge secondary metabolites are sought-after for their potential in pharmaceutical applications, and in the past, they were also used as taxonomic markers alongside the difficult and homoplasy-prone sponge morphology for species delineation (chemotaxonomy). The understanding Citation: Galitz, A.; Nakao, Y.; of phylogenetic distribution and distinctiveness of metabolites to sponge lineages is pivotal to reveal Schupp, P.J.; Wörheide, G.; pathways and evolution of compound production in sponges. This benefits the discovery rate and Erpenbeck, D. A Soft Spot for yield of bioprospecting for novel marine natural products by identifying lineages with high potential Chemistry–Current Taxonomic and Evolutionary Implications of Sponge of being new sources of valuable sponge compounds. -

(1104L) Animal Kingdom Part I

(1104L) Animal Kingdom Part I By: Jeffrey Mahr (1104L) Animal Kingdom Part I By: Jeffrey Mahr Online: < http://cnx.org/content/col12086/1.1/ > OpenStax-CNX This selection and arrangement of content as a collection is copyrighted by Jerey Mahr. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Collection structure revised: October 17, 2016 PDF generated: October 17, 2016 For copyright and attribution information for the modules contained in this collection, see p. 58. Table of Contents 1 (1104L) Animals introduction ....................................................................1 2 (1104L) Characteristics of Animals ..............................................................3 3 (1104L)The Evolutionary History of the Animal Kingdom ..................................11 4 (1104L) Phylum Porifera ........................................................................23 5 (1104L) Phylum Cnidaria .......................................................................31 6 (1104L) Phylum Rotifera & Phylum Platyhelminthes ........................................45 Glossary .............................................................................................53 Index ................................................................................................56 Attributions .........................................................................................58 iv Available for free at Connexions <http://cnx.org/content/col12086/1.1> Chapter 1 (1104L) Animals introduction1 -

Proposal for a Revised Classification of the Demospongiae (Porifera) Christine Morrow1 and Paco Cárdenas2,3*

Morrow and Cárdenas Frontiers in Zoology (2015) 12:7 DOI 10.1186/s12983-015-0099-8 DEBATE Open Access Proposal for a revised classification of the Demospongiae (Porifera) Christine Morrow1 and Paco Cárdenas2,3* Abstract Background: Demospongiae is the largest sponge class including 81% of all living sponges with nearly 7,000 species worldwide. Systema Porifera (2002) was the result of a large international collaboration to update the Demospongiae higher taxa classification, essentially based on morphological data. Since then, an increasing number of molecular phylogenetic studies have considerably shaken this taxonomic framework, with numerous polyphyletic groups revealed or confirmed and new clades discovered. And yet, despite a few taxonomical changes, the overall framework of the Systema Porifera classification still stands and is used as it is by the scientific community. This has led to a widening phylogeny/classification gap which creates biases and inconsistencies for the many end-users of this classification and ultimately impedes our understanding of today’s marine ecosystems and evolutionary processes. In an attempt to bridge this phylogeny/classification gap, we propose to officially revise the higher taxa Demospongiae classification. Discussion: We propose a revision of the Demospongiae higher taxa classification, essentially based on molecular data of the last ten years. We recommend the use of three subclasses: Verongimorpha, Keratosa and Heteroscleromorpha. We retain seven (Agelasida, Chondrosiida, Dendroceratida, Dictyoceratida, Haplosclerida, Poecilosclerida, Verongiida) of the 13 orders from Systema Porifera. We recommend the abandonment of five order names (Hadromerida, Halichondrida, Halisarcida, lithistids, Verticillitida) and resurrect or upgrade six order names (Axinellida, Merliida, Spongillida, Sphaerocladina, Suberitida, Tetractinellida). Finally, we create seven new orders (Bubarida, Desmacellida, Polymastiida, Scopalinida, Clionaida, Tethyida, Trachycladida). -

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS of the 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project March 2018 DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project Citation: Aguilar, R., García, S., Perry, A.L., Alvarez, H., Blanco, J., Bitar, G. 2018. 2016 Deep-sea Lebanon Expedition: Exploring Submarine Canyons. Oceana, Madrid. 94 p. DOI: 10.31230/osf.io/34cb9 Based on an official request from Lebanon’s Ministry of Environment back in 2013, Oceana has planned and carried out an expedition to survey Lebanese deep-sea canyons and escarpments. Cover: Cerianthus membranaceus © OCEANA All photos are © OCEANA Index 06 Introduction 11 Methods 16 Results 44 Areas 12 Rov surveys 16 Habitat types 44 Tarablus/Batroun 14 Infaunal surveys 16 Coralligenous habitat 44 Jounieh 14 Oceanographic and rhodolith/maërl 45 St. George beds measurements 46 Beirut 19 Sandy bottoms 15 Data analyses 46 Sayniq 15 Collaborations 20 Sandy-muddy bottoms 20 Rocky bottoms 22 Canyon heads 22 Bathyal muds 24 Species 27 Fishes 29 Crustaceans 30 Echinoderms 31 Cnidarians 36 Sponges 38 Molluscs 40 Bryozoans 40 Brachiopods 42 Tunicates 42 Annelids 42 Foraminifera 42 Algae | Deep sea Lebanon OCEANA 47 Human 50 Discussion and 68 Annex 1 85 Annex 2 impacts conclusions 68 Table A1. List of 85 Methodology for 47 Marine litter 51 Main expedition species identified assesing relative 49 Fisheries findings 84 Table A2. List conservation interest of 49 Other observations 52 Key community of threatened types and their species identified survey areas ecological importanc 84 Figure A1. -

Biodiversity Journal, 2020, 11 (4): 861–870

Biodiversity Journal, 2020, 11 (4): 861–870 https://doi.org/10.31396/Biodiv.Jour.2020.11.4.861.870 The biodiversity of the marine Heterobranchia fauna along the central-eastern coast of Sicily, Ionian Sea Andrea Lombardo* & Giuliana Marletta Department of Biological, Geological and Environmental Sciences - Section of Animal Biology, University of Catania, via Androne 81, 95124 Catania, Italy *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT The first updated list of the marine Heterobranchia for the central-eastern coast of Sicily (Italy) is here reported. This study was carried out, through a total of 271 scuba dives, from 2017 to the beginning of 2020 in four sites located along the Ionian coasts of Sicily: Catania, Aci Trezza, Santa Maria La Scala and Santa Tecla. Through a photographic data collection, 95 taxa, representing 17.27% of all Mediterranean marine Heterobranchia, were reported. The order with the highest number of found species was that of Nudibranchia. Among the study areas, Catania, Santa Maria La Scala and Santa Tecla had not a remarkable difference in the number of species, while Aci Trezza had the lowest number of species. Moreover, among the 95 taxa, four species considered rare and six non-indigenous species have been recorded. Since the presence of a high diversity of sea slugs in a relatively small area, the central-eastern coast of Sicily could be considered a zone of high biodiversity for the marine Heterobranchia fauna. KEY WORDS diversity; marine Heterobranchia; Mediterranean Sea; sea slugs; species list. Received 08.07.2020; accepted 08.10.2020; published online 20.11.2020 INTRODUCTION more researches were carried out (Cattaneo Vietti & Chemello, 1987). -

Marine Biodiversity Survey of Mermaid Reef (Rowley Shoals), Scott and Seringapatam Reef Western Australia 2006 Edited by Clay Bryce

ISBN 978-1-920843-50-2 ISSN 0313 122X Scott and Seringapatam Reef. Western Australia Marine Biodiversity Survey of Mermaid Reef (Rowley Shoals), Marine Biodiversity Survey of Mermaid Reef (Rowley Shoals), Scott and Seringapatam Reef Western Australia 2006 2006 Edited by Clay Bryce Edited by Clay Bryce Suppl. No. Records of the Western Australian Museum 77 Supplement No. 77 Records of the Western Australian Museum Supplement No. 77 Marine Biodiversity Survey of Mermaid Reef (Rowley Shoals), Scott and Seringapatam Reef Western Australia 2006 Edited by Clay Bryce Records of the Western Australian Museum The Records of the Western Australian Museum publishes the results of research into all branches of natural sciences and social and cultural history, primarily based on the collections of the Western Australian Museum and on research carried out by its staff members. Collections and research at the Western Australian Museum are centred on Earth and Planetary Sciences, Zoology, Anthropology and History. In particular the following areas are covered: systematics, ecology, biogeography and evolution of living and fossil organisms; mineralogy; meteoritics; anthropology and archaeology; history; maritime archaeology; and conservation. Western Australian Museum Perth Cultural Centre, James Street, Perth, Western Australia, 6000 Mail: Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, Western Australia 6986 Telephone: (08) 9212 3700 Facsimile: (08) 9212 3882 Email: [email protected] Minister for Culture and The Arts The Hon. John Day BSc, BDSc, MLA Chair of Trustees Mr Tim Ungar BEc, MAICD, FAIM Acting Executive Director Ms Diana Jones MSc, BSc, Dip.Ed Editors Dr Mark Harvey BSC, PhD Dr Paul Doughty BSc(Hons), PhD Editorial Board Dr Alex Baynes MA, PhD Dr Alex Bevan BSc(Hons), PhD Ms Ann Delroy BA(Hons), MPhil Dr Bill Humphreys BSc(Hons), PhD Dr Moya Smith BA(Hons), Dip.Ed. -

Comparative Ultrastructure of the Spermatogenesis of Three Species of Poecilosclerida (Porifera, Demospongiae)

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329545710 Comparative ultrastructure of the spermatogenesis of three species of Poecilosclerida (Porifera, Demospongiae) Article in Zoomorphology · December 2018 DOI: 10.1007/s00435-018-0429-4 CITATION READS 1 72 4 authors: Vivian Vasconcellos Philippe Willenz Universidade Federal da Bahia Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences 6 PUBLICATIONS 118 CITATIONS 85 PUBLICATIONS 1,200 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Alexander V Ereskovsky Emilio Lanna French National Centre for Scientific Research Universidade Federal da Bahia 202 PUBLICATIONS 3,317 CITATIONS 31 PUBLICATIONS 228 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Organization and patterning of sponge epithelia View project Sponges from Peru - Esponjas del Perú View project All content following this page was uploaded by Alexander V Ereskovsky on 25 April 2020. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Zoomorphology https://doi.org/10.1007/s00435-018-0429-4 ORIGINAL PAPER Comparative ultrastructure of the spermatogenesis of three species of Poecilosclerida (Porifera, Demospongiae) Vivian Vasconcellos1,2 · Philippe Willenz3,4 · Alexander Ereskovsky5,6 · Emilio Lanna1,2 Received: 15 August 2018 / Revised: 26 November 2018 / Accepted: 30 November 2018 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract The spermatogenesis of Porifera is still relatively poorly understood. In the past, it was accepted that all species presented a primitive-type spermatozoon, lacking special structures and acrosome. Nonetheless, a very peculiar spermatogenesis resulting in a sophisticated V-shaped spermatozoon with an acrosome was found in Poecilosclerida. -

Omnibus Essential Fish Habitat (Efh) Amendment 2 Draft Environmental Impact Statement

New England Fishery Management Council 50 WATER STREET | NEWBURYPORT, MASSACHUSETTS 01950 | PHONE 978 465 0492 | FAX 978 465 3116 E.F. “Terry” Stockwell III, Chairman | Thomas A. Nies, Executive Director OMNIBUS ESSENTIAL FISH HABITAT (EFH) AMENDMENT 2 DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Appendix D: The Swept Area Seabed Impact (SASI) approach: a tool for analyzing the effects of fishing on Essential Fish Habitat Appendix D: The Swept Area Seabed Impact Approach This document was prepared by the following members of the NEFMC Habitat Plan Development team, with feedback from the NEFMC Habitat Oversight Committee, NEFMC Habitat Advisory Panel, and interested members of the public. Michelle Bachman, NEFMC staff Peter Auster, University of Connecticut Chad Demarest, NOAA/Northeast Fisheries Science Center Steve Eayrs, Gulf of Maine Research Institute Kathyrn Ford, Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Jon Grabowski, Gulf of Maine Research Institute Brad Harris, University of Massachusetts School of Marine Science and Technology Tom Hoff, Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council Mark Lazzari, Maine Department of Marine Resources Vincent Malkoski, Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries Dave Packer, NOAA/ Northeast Fisheries Science Center David Stevenson, NOAA/Northeast Regional Office Page Valentine, U.S. Geological Survey January 2011 Page 2 of 257 Appendix D: The Swept Area Seabed Impact Approach Table of Contents 1.0 OVERVIEW OF THE SWEPT AREA SEABED IMPACT MODEL ........... 13 2.0 DEFINING HABITAT ...................................................................................... -

Table of Contents

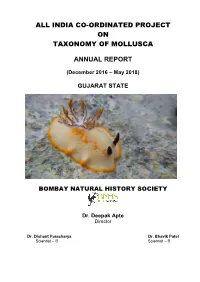

ALL INDIA CO-ORDINATED PROJECT ON TAXONOMY OF MOLLUSCA ANNUAL REPORT (December 2016 – May 2018) GUJARAT STATE BOMBAY NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY Dr. Deepak Apte Director Dr. Dishant Parasharya Dr. Bhavik Patel Scientist – B Scientist – B All India Coordinated Project on Taxonomy – Mollusca , Gujarat State Acknowledgements We are thankful to the Department of Forest and Environment, Government of Gujarat, Mr. G. K. Sinha, IFS HoFF and PCCF (Wildlife) for his guidance and cooperation in the work. We are thankful to then CCF Marine National Park and Sanctuary, Mr. Shyamal Tikader IFS, Mr. S. K. Mehta IFS and their team for the generous support, We take this opportunity to thank the entire team of Marine National Park and Sanctuary. We are thankful to all the colleagues of BNHS who directly or indirectly helped us in our work. We specially thank our field assistant, Rajesh Parmar who helped us in the field work. All India Coordinated Project on Taxonomy – Mollusca , Gujarat State 1. Introduction Gujarat has a long coastline of about 1650 km, which is mainly due to the presence of two gulfs viz. the Gulf of Khambhat (GoKh) and Gulf of Kachchh (GoK). The coastline has diverse habitats such as rocky, sandy, mangroves, coral reefs etc. The southern shore of the GoK in the western India, notified as Marine National Park and Sanctuary (MNP & S), harbours most of these major habitats. The reef areas of the GoK are rich in flora and fauna; Narara, Dwarka, Poshitra, Shivrajpur, Paga, Boria, Chank and Okha are some of these pristine areas of the GoK and its surrounding environs.