Arxiv:1906.06171V2 [Cs.SD] 1 Jun 2020 Therefore Be Considered Solutions to the Problem of Partitioning of Imperfect fifths – Perfect fifths with a Tolerance for Error

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Absolute and Relative Pitch Processing in the Human Brain: Neural and Behavioral Evidence

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/526541; this version posted March 18, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Absolute and relative pitch processing in the human brain: Neural and behavioral evidence Simon Leipold a, Christian Brauchli a, Marielle Greber a, Lutz Jäncke a, b, c Author Affiliations a Division Neuropsychology, Department of Psychology, University of Zurich, 8050 Zurich, Switzerland b University Research Priority Program (URPP), Dynamics of Healthy Aging, University of Zurich, 8050 Zurich, Switzerland c Department of Special Education, King Abdulaziz University, 21589 Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Corresponding Authors Simon Leipold Binzmühlestrasse 14, Box 25 CH-8050 Zürich Switzerland [email protected] Lutz Jäncke Binzmühlestrasse 14, Box 25 CH-8050 Zürich Switzerland [email protected] Keywords Absolute Pitch, Multivariate Pattern Analysis, Neural Efficiency, Pitch Processing, fMRI Acknowledgements This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), grant no. 320030_163149 to LJ. We thank our research interns Anna Speckert, Chantal Oderbolz, Désirée Yamada, Fabian Demuth, Florence Bernays, Joëlle Albrecht, Kathrin Baur, Laura Keller, Marilena Wilding, Melek Haçan, Nicole Hedinger, Pascal Misala, Petra Meier, Sarah Appenzeller, Tenzin Dotschung, Valerie Hungerbühler, Vanessa Vallesi, -

TUNING JUDGMENTS 1 1 2 3 4 Does Tuning Influence Aesthetic

TUNING JUDGMENTS 1 1 2 3 4 5 Does Tuning Influence Aesthetic Judgments of Music? Investigating the Generalizability 6 of Absolute Intonation Ability 7 8 Stephen C. Van Hedger 1 2 and Huda Khudhair 1 9 10 11 1 Department of Psychology, Huron University College at Western 12 2 Department of Psychology & Brain and Mind Institute, University of Western Ontario 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Author Note 21 Word Count (Main Body): 7,535 22 Number of Tables: 2 23 Number of Figures: 2 24 We have no known conflict of interests to disclose. 25 All materials and data associated with this manuscript can be accessed via Open Science 26 Framework (https://osf.io/zjcvd/) 27 Correspondences should be sent to: 28 Stephen C. Van Hedger, Department of Psychology, Huron University College at Western: 1349 29 Western Road, London, ON, N6G 1H3 Canada [email protected] 30 31 32 TUNING JUDGMENTS 2 1 Abstract 2 Listening to music is an enjoyable activity for most individuals, yet the musical factors that relate 3 to aesthetic experiences are not completely understood. In the present paper, we investigate 4 whether the absolute tuning of music implicitly influences listener evaluations of music, as well 5 as whether listeners can explicitly categorize musical sounds as “in tune” versus “out of tune” 6 based on conventional tuning standards. In Experiment 1, participants rated unfamiliar musical 7 excerpts, which were either tuned conventionally or unconventionally, in terms of liking, interest, 8 and unusualness. In Experiment 2, participants were asked to explicitly judge whether several 9 types of musical sounds (isolated notes, chords, scales, and short excerpts) were “in tune” or 10 “out of tune.” The results suggest that the absolute tuning of music has no influence on listener 11 evaluations of music (Experiment 1), and these null results are likely caused, in part, by an 12 inability for listeners to explicitly differentiate in-tune from out-of-tune musical excerpts 13 (Experiment 2). -

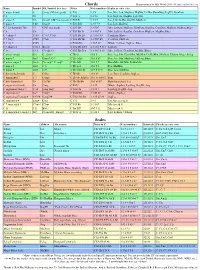

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM Chords Charts written by Mal Webb 2014-18 http://malwebb.com Name Symbol Alt. Symbol (best first) Notes Note numbers Scales (in order of fit). C major (triad) C Cmaj, CM (not good) C E G 1 3 5 Ion, Mix, Lyd, MajPent, MajBlu, DoHar, HarmMaj, RagPD, DomPent C 6 C6 C E G A 1 3 5 6 Ion, MajPent, MajBlu, Lyd, Mix C major 7 C∆ Cmaj7, CM7 (not good) C E G B 1 3 5 7 Ion, Lyd, DoHar, RagPD, MajPent C major 9 C∆9 Cmaj9 C E G B D 1 3 5 7 9 Ion, Lyd, MajPent C 7 (or dominant 7th) C7 CM7 (not good) C E G Bb 1 3 5 b7 Mix, LyDom, PhrDom, DomPent, RagCha, ComDim, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 9 C9 C E G Bb D 1 3 5 b7 9 Mix, LyDom, RagCha, DomPent, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 7 sharp 9 C7#9 C7+9, C7alt. C E G Bb D# 1 3 5 b7 #9 ComDim, Blues C 7 flat 9 C7b9 C7alt. C E G Bb Db 1 3 5 b7 b9 ComDim, PhrDom C 7 flat 5 C7b5 C E Gb Bb 1 3 b5 b7 Whole, LyDom, SupLoc, Blues C 7 sharp 11 C7#11 Bb+/C C E G Bb D F# 1 3 5 b7 9 #11 LyDom C 13 C 13 C9 add 13 C E G Bb D A 1 3 5 b7 9 13 Mix, LyDom, DomPent, MajBlu, Blues C minor (triad) Cm C-, Cmin C Eb G 1 b3 5 Dor, Aeo, Phr, HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin, MinPent, Ukdom, Blues, Pelog C minor 7 Cm7 Cmin7, C-7 C Eb G Bb 1 b3 5 b7 Dor, Aeo, Phr, MinPent, UkDom, Blues C minor major 7 Cm∆ Cm maj7, C- maj7 C Eb G B 1 b3 5 7 HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin C minor 6 Cm6 C-6 C Eb G A 1 b3 5 6 Dor, MelMin C minor 9 Cm9 C-9 C Eb G Bb D 1 b3 5 b7 9 Dor, Aeo, MinPent C diminished (triad) Cº Cdim C Eb Gb 1 b3 b5 Loc, Dim, ComDim, SupLoc C diminished 7 Cº7 Cdim7 C Eb Gb A(Bbb) 1 b3 b5 6(bb7) Dim C half diminished Cø -

Philosophy of Music Education

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Honors Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2017 Philosophy of Music Education Mary Elizabeth Barba Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/honors Part of the Music Education Commons, and the Music Pedagogy Commons Recommended Citation Barba, Mary Elizabeth, "Philosophy of Music Education" (2017). Honors Theses and Capstones. 322. https://scholars.unh.edu/honors/322 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Philosophy of Music Education Mary Barba Dr. David Upham December 9, 2016 Barba 1 Philosophy of Music Education A philosophy of music education refers to the value of music, the value of teaching music, and how to practically utilize those values in the music classroom. Bennet Reimer, a renowned music education philosopher, wrote the following, regarding the value of studying the philosophy of music education: “To the degree we can present a convincing explanation of the nature of the art of music and the value of music in the lives of people, to that degree we can present a convincing picture of the nature of music education and its value for human life.”1 In this thesis, I will explore the philosophies of Emile Jacques-Dalcroze, Carl Orff, Zoltán Kodály, Bennett Reimer, and David Elliott, and suggest practical applications of their philosophies in the orchestral classroom, especially in the context of ear training and improvisation. -

Effects of Harmonics on Relative Pitch Discrimination in a Musical Context

Perception & Psychophysics 1996, 58 (5), 704-712 Effects of harmonics on relative pitch discrimination in a musical context LAUREL J. TRAINOR McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada The contribution of different harmonics to pitch salience in a musical context was examined by re quiring subjects to discriminate a small (% semitone) pitch change in one note of a melody that re peated in transposition. In Experiment 1,performance was superior when more harmonics were pres ent (first five vs. fundamental alone) and when the second harmonic (of tones consisting of the first two harmonics) was in tune compared with when it was out of tune. In Experiment 2, the effects ofhar monies 6 and 8, which stand in octave-equivalent simple ratios to the fundamental (2:3 and 1:2, re spectively) were compared with harmonics 5 and 7, which stand in more complex ratios (4:5 and 4:7, respectively). When the harmonics fused into a single percept (tones consisting of harmonics 1,2, and one of 5, 6, 7, or 8), performance was higher when harmonics 6 or 8 were present than when harmon ics 5 or 7 were present. When the harmonics did not fuse into a single percept (tones consisting of the fundamental and one of 5, 6, 7, or 8), there was no effect of ratio simplicity. This paper examines the contribution of different har gion depended to some extent on the fundamental fre monics to relative pitch discrimination in a musical con quency: The fourth and higher harmonics dominated for text. Relative pitch discrimination refers to the ability to fundamental frequencies up to 350 Hz, the third and higher compare the pitch interval (i.e., distance on a log frequency for fundamentals between 350 and 700 Hz, the second and scale) between one set oftwo tones and another, where the higher for fundamental frequencies between 700 and fundamentals ofthe tones are at different absolute frequen 1400 Hz, and the first for frequencies above 1400 Hz. -

3 Manual Microtonal Organ Ruben Sverre Gjertsen 2013

3 Manual Microtonal Organ http://www.bek.no/~ruben/Research/Downloads/software.html Ruben Sverre Gjertsen 2013 An interface to existing software A motivation for creating this instrument has been an interest for gaining experience with a large range of intonation systems. This software instrument is built with Max 61, as an interface to the Fluidsynth object2. Fluidsynth offers possibilities for retuning soundfont banks (Sf2 format) to 12-tone or full-register tunings. Max 6 introduced the dictionary format, which has been useful for creating a tuning database in text format, as well as storing presets. This tuning database can naturally be expanded by users, if tunings are written in the syntax read by this instrument. The freely available Jeux organ soundfont3 has been used as a default soundfont, while any instrument in the sf2 format can be loaded. The organ interface The organ window 3 MIDI Keyboards This instrument contains 3 separate fluidsynth modules, named Manual 1-3. 3 keysliders can be played staccato by the mouse for testing, while the most musically sufficient option is performing from connected MIDI keyboards. Available inputs will be automatically recognized and can be selected from the menus. To keep some of the manuals silent, select the bottom alternative "to 2ManualMicroORGANircamSpat 1", which will not receive MIDI signal, unless another program (for instance Sibelius) is sending them. A separate menu can be used to select a foot trigger. The red toggle must be pressed for this to be active. This has been tested with Behringer FCB1010 triggers. Other devices could possibly require adjustments to the patch. -

Construction and Verification of the Scale Detection Method for Traditional Japanese Music – a Method Based on Pitch Sequence of Musical Scales –

International Journal of Affective Engineering Vol.12 No.2 pp.309-315 (2013) Special Issue on KEER 2012 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Construction and Verification of the Scale Detection Method for Traditional Japanese Music – A Method Based on Pitch Sequence of Musical Scales – Akihiro KAWASE Department of Corpus Studies, National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics, 10-2 Midori-cho, Tachikawa City, Tokyo 190-8561, Japan Abstract: In this study, we propose a method for automatically detecting musical scales from Japanese musical pieces. A scale is a series of musical notes in ascending or descending order, which is an important element for describing the tonal system (Tonesystem) and capturing the characteristics of the music. The study of scale theory has a long history. Many scale theories for Japanese music have been designed up until this point. Out of these, we chose to formulate a scale detection method based on Seiichi Tokawa’s scale theories for traditional Japanese music, because Tokawa’s scale theories provide a versatile system that covers various conventional scale theories. Since Tokawa did not describe any of his scale detection procedures in detail, we started by analyzing his theories and understanding their characteristics. Based on the findings, we constructed the scale detection method and implemented it in the Java Runtime Environment. Specifically, we sampled 1,794 works from the Nihon Min-yo Taikan (Anthology of Japanese Folk Songs, 1944-1993), and performed the method. We compared the detection results with traditional research results in order to verify the detection method. If the various scales of Japanese music can be automatically detected, it will facilitate the work of specifying scales, which promotes the humanities analysis of Japanese music. -

Helmholtz's Dissonance Curve

Tuning and Timbre: A Perceptual Synthesis Bill Sethares IDEA: Exploit psychoacoustic studies on the perception of consonance and dissonance. The talk begins by showing how to build a device that can measure the “sensory” consonance and/or dissonance of a sound in its musical context. Such a “dissonance meter” has implications in music theory, in synthesizer design, in the con- struction of musical scales and tunings, and in the design of musical instruments. ...the legacy of Helmholtz continues... 1 Some Observations. Why do we tune our instruments the way we do? Some tunings are easier to play in than others. Some timbres work well in certain scales, but not in others. What makes a sound easy in 19-tet but hard in 10-tet? “The timbre of an instrument strongly affects what tuning and scale sound best on that instrument.” – W. Carlos 2 What are Tuning and Timbre? 196 384 589 amplitude 787 magnitude sample: 0 10000 20000 30000 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 time: 0 0.23 0.45 0.68 frequency in Hz Tuning = pitch of the fundamental (in this case 196 Hz) Timbre involves (a) pattern of overtones (Helmholtz) (b) temporal features 3 Some intervals “harmonious” and others “discordant.” Why? X X X X 1.06:1 2:1 X X X X 1.89:1 3:2 X X X X 1.414:1 4:3 4 Theory #1:(Pythagoras ) Humans naturally like the sound of intervals de- fined by small integer ratios. small ratios imply short period of repetition short = simple = sweet Theory #2:(Helmholtz ) Partials of a sound that are close in frequency cause beats that are perceived as “roughness” or dissonance. -

250 + Musical Scales and Scalecodings

250 + Musical Scales and Scalecodings Number Note Names Of Notes Ascending Name Of Scale In Scale from C ScaleCoding Major Suspended 4th Chord 4 C D F G 3/0/2 Major b7 Suspend 4th Chord 4 C F G Bb 3/0/3 Major Pentatonic 5 C D E G A 4/0/1 Ritusen Japan, Scottish Pentatonic 5 C D F G A 4/0/2 Egyptian \ Suspended Pentatonic 5 C D F G Bb 4/0/3 Blues Pentatonic Minor, Hard Japan 5 C Eb F G Bb 4/0/4 Major 7-b5 Chord \ Messiaen Truncated Mode 4 C Eb G Bb 4/3/4 Minor b7 Chord 4 C Eb G Bb 4/3/4 Major Chord 3 C E G 4/34/1 Eskimo Tetratonic 4 C D E G 4/4/1 Lydian Hexatonic 6 C D E G A B 5/0/1 Scottish Hexatonic 6 C D E F G A 5/0/2 Mixolydian Hexatonic 6 C D F G A Bb 5/0/3 Phrygian Hexatonic 6 C Eb F G Ab Bb 5/0/5 Ritsu 6 C Db Eb F Ab Bb 5/0/6 Minor Pentachord 5 C D Eb F G 5/2/4 Major 7 Chord 4 C E G B 5/24/1 Phrygian Tetrachord 4 C Db Eb F 5/24/6 Dorian Tetrachord 4 C D Eb F 5/25/4 Major Tetrachord 4 C D E F 5/35/2 Warao Tetratonic 4 C D Eb Bb 5/35/4 Oriental 5 C D F A Bb 5/4/3 Major Pentachord 5 C D E F G 5/5/2 Han-Kumo? 5 C D F G Ab 5/23/5 Lydian, Kalyan F to E ascending naturals 7 C D E F# G A B 6/0/1 Ionian, Major, Bilaval C to B asc. -

ANNEXURE Credo Theory of Music Training Programme GRADE 5 by S

- 1 - ANNEXURE Credo Theory of Music training programme GRADE 5 By S. J. Cloete Copyright reserved © 2017 BLUES (JAZZ). (Unisa learners only) WHAT IS THE BLUES? The Blues is a musical genre* originated by African Americans in the Deep South of the USA around the end of the 19th century. The genre developed from roots in African musical traditions, African-American work songs, spirituals and folk music. The first appearance of the Blues is often dated to after the ending of slavery in America. The slavery was a sad time in history and this melancholic sound is heard in Blues music. The Blues, ubiquitous in jazz and rock ‘n’ roll music, is characterized by the call-and- response* pattern, the blues scale (which you are about to learn) and specific chord progressions*, of which the twelve-bar blues* is the most common. Blue notes*, usually 3rds or 5ths flattened in pitch, are also an essential part of the sound. A swing* rhythm and walking bass* are commonly used in blues, country music, jazz, etc. * Musical genre: It is a conventional category that identifies some music as belonging to a shared tradition or set of conventions, e.g. the blues, or classical music or opera, etc. They share a certain “basic musical language”. * Call-and-response pattern: It is a succession of two distinct phrases, usually played by different musicians (groups), where the second phrase is heard as a direct commentary on or response to the first. It can be traced back to African music. * Chord progressions: The blues follows a certain chord progression and the th th 7 b harmonic 7 (blues 7 ) is used much of the time (e.g. -

Course Name : Indonesian Cultural Arts – Karawitan (Seni Budaya

Course Name : Indonesian Cultural Arts – Karawitan (Seni Budaya Indonesia – Karawitan) Course Code / Credits : BDU 2303/ 3 SKS Teaching Period : January-June Semester Language Instruction : Indonesian Department : Sastra Nusantara Faculty : Faculty of Arts and Humanities (FIB) Course Description The course of Indonesian Cultural Arts (Karawitan) is a compulsory course for (regular) students of Faculty of Cultural Sciences Universitas Gadjah Mada, especially for the first and second semesters. The course is held every semester and is offered and can be taken by every student from semester 1 to 2. There are no prerequisites for Karawitan courses. The position of Indonesian Culture Arts (Karawitan) as the compulsory course serves to introduce the students to one aspect of Indonesian (or Javanese) art and culture and the practical knowledge related to the performance of traditional Javanese musical instruments, namely gamelan. This course also aims to provide both introduction and theoretical and practical understanding for the students of the Faculty of Cultural Science on gamelan instrument techniques, namely gendhing technique, that is found in Karawitan. Topics in this course include identification of Javanese gamelan instruments, exploration of tones in Javanese gamelan, gendhing instrument method and practice, as well as observation of traditional art performances. Proportionally, 30% of these courses contains briefing theoretical insights, 40% contains gamelan practice, and 30% contains provision of experience in a form of group collaboration and interaction Course Objectives The course of Indonesian Culture Arts (Karawitan) in general aims to provide theoretical and practical supplies through skill, application, and carefulness to recognize various instruments of Gamelan. Through this course, students are observant in identifying the various instruments of the gamelan and its application as instrumental and vocal art in karawitan. -

In Search of the Perfect Musical Scale

In Search of the Perfect Musical Scale J. N. Hooker Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, USA [email protected] May 2017 Abstract We analyze results of a search for alternative musical scales that share the main advantages of classical scales: pitch frequencies that bear simple ratios to each other, and multiple keys based on an un- derlying chromatic scale with tempered tuning. The search is based on combinatorics and a constraint programming model that assigns frequency ratios to intervals. We find that certain 11-note scales on a 19-note chromatic stand out as superior to all others. These scales enjoy harmonic and structural possibilities that go significantly beyond what is available in classical scales and therefore provide a possible medium for innovative musical composition. 1 Introduction The classical major and minor scales of Western music have two attractive characteristics: pitch frequencies that bear simple ratios to each other, and multiple keys based on an underlying chromatic scale with tempered tuning. Simple ratios allow for rich and intelligible harmonies, while multiple keys greatly expand possibilities for complex musical structure. While these tra- ditional scales have provided the basis for a fabulous outpouring of musical creativity over several centuries, one might ask whether they provide the natural or inevitable framework for music. Perhaps there are alternative scales with the same favorable characteristics|simple ratios and multiple keys|that could unleash even greater creativity. This paper summarizes the results of a recent study [8] that undertook a systematic search for musically appealing alternative scales. The search 1 restricts itself to diatonic scales, whose adjacent notes are separated by a whole tone or semitone.