Development of the HELIUS Food Frequency Questionnaires: Ethnic-Specific Questionnaires to Assess the Diet of a Multiethnic Population in the Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

@ ERDMAN DINING HALL Open for Lunch Tuesday August 28Th

@ ERDMAN DINING HALL Saturday 8/25 Sunday 8/26 Monday 8/27 Tuesday 8/28 Wednesday 8/29 Thursday 8/30 Friday 8/31 BREAKFAST BREAKFAST Oatmeal V & Grits V Oatmeal V & Grits V Belgian Waffles Belgian Waffles* Oreo Muffin Oreo Muffin V Weekday Hours of Operation MENU ITEMS IDENTIFIED WITH Corn Muffins* Monday– Friday Corn Muffins V Shredded Potatoes* Breakfast Weekend Hours of Operation THIS MARK ARE PREPARED IN A Home-fried Sliced Potatoes V Chocolate Chip Pancakes* 7.30am-9am Saturday-Sunday = VEGETARIAN French Toast Sticks* Pork Sausage ∆ & Vegan Sausage Continental Breakfast * COMMON KITCHEN TO BE GLUTEN Continental Breakfast Bacon ∆ & Vegan Sausage Hard Cooked Eggs ∆* 9am-11am 7am-9.30am (Saturday Only) FREE, DAIRY FREE, SHELLFISH FREE Lunch Brunch Hard Cooked Eggs ∆* Scrambled Eggs ∆* 10am-1.30pm V = VEGAN 11am-1.30pm & NUT FREE.BMCDS CAN NOT Scrambled Eggs ∆* Assorted Bagels Dinner Dinner & Firehouse Donuts* 5pm-7pm 5pm-7pm ∆ = PREPARED WHEAT FREE GUARANTEE THAT CROSS-CONTACT Assorted Bagels* Yogurt Bar & Omelet Bar Yogurt Bar & Omelet Bar HAS NOT OCCURRED Firehouse Donuts* Sun-dried Tomato, Create your Congee V∆ Mushroom, Spinach & Tofu Quiche INTERNATIONAL LUNCH CUSTOMS LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH Fire Roasted Tomato Soup Tuscan Minestrone Smoked Turkey Cobb Salad New England Clam Chowder Creole Beef & Okra Soup ∆ Grilled Pesto Chicken Sandwich Blackened Salmon Nicoise Lentil Soup V∆ Local Mushroom Bisque* Fingerling Potatoes Dave’s Crabcakes Pulled BBQ Carrot Sandwiches Cajun Marinated Chicken Breast Singapore Street Noodles Grilled Asparagus -

Menu Week 1 Day 1: Lunch: Ajiaco, Hungarian Seitan Stew Dinner: Zucchini Bisque, Seared Whitefish with Artichokes, Apple Turnover

The Pritikin® Eating Plan at Home Menu Week 1 Day 1: Lunch: Ajiaco, Hungarian Seitan Stew Dinner: Zucchini Bisque, Seared Whitefish with Artichokes, Apple Turnover Day 2: Lunch: Black Bean , Lentil & Spinach Stew Dinner: Lentil, Roasted Bison, Strawberry Yogurt Swirl Day 3: Lunch: Garbanzo Soup, Spinach Ravioli with Black Bean Sauce Dinner: Okra Soup, Seared Trout with Pickled Veggies, Cheese Cake Day 4: Lunch: Barley Shiitake Soup, Mango & Seitan Stew Dinner: Tuscan Leek Soup, Seared Salmon with Potato Hash, Cherry Pie Day 5: Lunch: Black Eyed Pea Soup, Pasta with “Meatballs” Dinner: Mexican Vegetables, Roast Turkey Sweet Potato, Mango Parfait Day 6: Lunch, Calabaza Soup, Vegetable Pizza Dinner: Eight Bean Soup, Lemon Mahi Mahi, Poached Pear Day 7: Lunch: Vegetable Soup, Vegetarian Crab Cake Dinner: Sweet & Sour Cabbage Soup, Coriander Scallops, Jewel of Fruit Pie Choose any two sides of vegetables for lunch and choose any two sides of vegetables for dinner. Choose any salad dressing for your lunch and dinner salad. The Pritikin® Eating Plan at Home Menu Week 2 Day 1: Lunch: Green & Chile Tomato, Vegetable Lasagna Dinner: Wild Mushroom, Fish en Pappiolette, Cherries Jubilee Day 2: Lunch: Minestrone, Pasta Tomato/Mushroom Dinner: Yellow Split Pea, Roasted Bison, Pumpkin Pie Day 3: Lunch: Tomato Basil, Vegetable Stuffed Shells with Tomato Sauce Dinner: White Bean Soup, Poached Salmon with Roasted Potatoes, Mango Compote Day 4: Lunch: Orange Saffron Soup, African Stew Dinner: Sweet Potato & Kale Soup, Roasted Lobster, Melon Tapioca Day 5: Lunch: Ajiaco Soup, White Bean & Mushroom Ragout Dinner: Vegetable Soup, Jerked Chicken Breast, Apple Turnover Day 6: Lunch: Lentil Soup, Vegetable Garden Pizza Dinner: Mexican Vegetable Soup, Whitefish with Orange & Thyme, Cheesecake Day 7: Lunch: Eight Bean Soup, Shepherd’s Pie Dinner: Garbanzo, Stuffed Trout, Jewel of Fruit Pie Choose any two sides of vegetables for lunch and choose any two sides of vegetables for dinner. -

Classic Nigerian Food Recipes

CLASSIC NIGERIAN FOOD RECIPES This ebook is an Intellectual Property of Michael Toye Faleti © All rights reserved The content of this ebook is not warranted for correctness, and is used by the reader at his/her own will. No other warranty is given for using the content of this ebook. 1 INTRODUCTION This ebook is written as a guide to learning how to cook Nigerian foods. You will find fifteen main recipes of some of the most popular dishes enjoyed all across southern Nigeria. So why make an ebook about Nigerian food recipes? Firstly, I love Nigerian foods. I think Nigerian cuisine has penerated a lot of cultures across the world and many people are becoming more curious of African cuisine in general. However, this ebook is for women and maybe men who are Nigerians or have been influenced by the culture through marriage, family or friendship to broaden their knowledge about Nigerian cuisine and develop their confidence in the kitchen. And most importantly for the young women starting out wanting to become better skilled at the Nigerian culinary arts. If you are Yoruba and have always wanted to learn how to cook Ibo food then there are plenty of Ibo food recipes here to get you started. Or maybe you learned to cook Nigerian foods in countries like the U.S, Great Britain, South Africa or elsewhere and want to improve on the recipes you know or learn some new ones. This ebook will take your cooking to the next level by extending the range of Nigerian foods you can cook and teach you how to combine native ingredients to get the most authentic flavour and taste. -

Call 2Go Services for Delivery 206-246-2626 Online at Www

Call 2Go Services for Delivery 206-246-2626 Online at www.2goservices.com 1 Hours of operation: About 2Go Services Monday–Thursday 8:30am–10pm, Friday 8:30am–11pm Place your food order from any of the restaurants listed in this guide by calling us at Saturday 4pm–11pm, Sunday 5pm–10pm 206-246-2626, by ordering online at 2GoServices.com, or by faxing us Individual restaurant hours are listed at the bottom of each page. at 425-917-0776 (please call to confirm that your fax was received). DELIVERY FEES A single delivery fee is charged per restaurant regardless of the size of the order. You may order from as many restaurants as you wish but a delivery fee will apply for each restaurant. MINIMUM FOOD ORDER total is $15 per restaurant. Average delivery time is one hour. Delivery times vary due to meal preparation time and traffic conditions. CATERING Catering is available 24 hours a day with advance notice. Most items can be served buffet style. See catering and group specials on page 75. GRATUITIES Our drivers work very hard to insure that your order is complete, on time and arrives at the appropriate temperature. Gratuities are accepted and appreciated, but are not included in the delivery fee. A suggested 12% gratuity appears on orders over $100 – this gratuity can be modified at your discretion to reflect the quality of service received. PAYMENT METHOD We welcome cash, MasterCard, Visa, Discover and American Express. Sorry, but personal checks are not accepted. Corporate billing is also available with prior credit approval. -

Xmlns:W="Urn:Schemas-Microsoft-Com

Edit and Find may help in locating desired links. If links don’t work you can try copying and pasting into Netscape or Explorer Browser Definitions of International Food Related Items (Revised 2/14) [A] [B] [C] [D] [E] [F] [G] [H] [I] [J] [K] [L] [M] [N] [O] [P] [Q] [R] [S] [T] [U] [V] [W] [X] [Y] [Z] A Aaloo Baingan (Pakistani): Potato and aubergines (eggplant) Aaloo Ghobi (Paskistani): Spiced potato and cauliflower Aaloo Gosht Kari (Pakistani): Potato with lamb Aam (Hindu): Mango Aam Ka Achar (Indian): Pickled mango Aarici Halwa (Indian): A sweet made of rice and jaggery Abaisee: (French): A sheet of thinly rolled, puff pastry mostly used in desserts. Abalone: A mollusk found along California, Mexico, and Japan coast. The edible part is the foot muscle. The meat is tough and must be tenderized before cooking. Abats: Organ meat Abbacchio: Young lamb used much like veal Abena (Spanish): Oats Abenkwan (Ghanaian): A soup made from palm nuts and eaten with fufu. It is usually cooked with fresh or smoked meat or fish. Aboukir: (Swiss): Dessert made with sponge cake and chestnut flavored alcohol based crème. Abuage: Tofu fried packets cooked in sweet cooking sake, soy sauce, and water. Acapurrias (Spanish, Puerto Rico): Banana croquettes stuffed with beef or pork. Page 1 of 68 Acar (Malaysian): Pickle with a sour sweet taste served with a rice dish. Aceite (Spanish): Oil Aceituna: (Spanish): Olive Acetomel: A mixture of honey and vinegar, used to preserve fruit. Accrats (Hatian, Creol): Breaded fried cod, also called marinades. Achar (East Indian): Pickled and salted relish that can be sweet or hot. -

Soups Stews Chowders Chilis & Other Soupy Things

Soups Stews Chowders Chilis & Other Soupy Things To make a good soup, the pot must only simmer or smile. —French Proverb F 1 The Magic of Soups Satisfies the Soul johnclinockart.com "Beautiful soup, so rich and green Waiting in a hot tureen! Who for such dainties would not stoop? Soup of the evening, beautiful soup! Beautiful soup! Who cares for fish Game, or any other dish? Who would not give all else for two Pennyworth of beautiful soup?" Lewis Carroll, ‘Alice in Wonderland’ F 2 Beef-Based Soups & Stews skinnyms.com Texas Bean Soup This recipe card says it’s from someone named Ginger. She closes her recipe card with a hand-written “Happy eating!” agoodappetite.blogspot.com 3 6 12 SERVINGS Red Beans & Rice Soup ¾ 1½-2 3-4 Cups bean mix 20 SERVINGS 1-2 2-3 4-6 Cups water ½ 1 2 Large onions, chopped 1 Onion, chopped ½ 1-2 2-4 Cloves garlic, minced Garlic to taste Ham soup bone 3 Tbsp. olive oil (or other seasoning meat) 4 Carrots, sliced Salt to taste 4 Celery ribs, sliced ⅓ ⅔ 1⅓ Cup rice or barley (optional) 1 Green Pepper, chopped ½ 1 2 Cans tomatoes (optional) 12 Cups chicken broth Grated cheese 2 Cups red beans, soaked overnight 1 tsp. salt Rinse and soak bean mix overnight. Drain and place in 1 tsp. fresh ground pepper saucepan with water. Add onion, garlic and hambone. Salt to 1½ tsp. thyme taste. Add rice or barley, if using. Simmer, covered, for 1-2 1½ tsp. marjoram hours, stirring occasionally. Add tomatoes, if using, and heat 1 14-ounce can chopped tomatoes with juice, chopped through. -

Kentucky Wic Farmers' Market Nutrition Program (Fmnp)

KENTUCKY WIC FARMERS’ MARKET NUTRITION PROGRAM (FMNP) RECIPE BOOK Recipes for Farmers’ Market Fruits and Vegetables “WIC is a registered service mark of the Department of Agriculture for USDA’s Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children.” This institution is an equal opportunity provider. Developed By: Department for Public Health Division of Maternal and Child Health Nutrition Services Branch 275 East Main Street, HS2W-D Frankfort, Kentucky 40621 (502) 564-3827 Revised March 2019 For questions contact: [email protected] Or (502) 564-3827 In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, sex, religious creed, disability, age, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g. Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.), should contact the Agency (State or local) where they applied for benefits. Individuals who are deaf, hard of hearing or have speech disabilities may contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program complaint of discrimination, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, (AD-3027) found online at: How to File a Complaint, and at any USDA office, or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. -

Noodle Types

noodle types = Favorites = Gluten Free V = Vegetarian = Contains Dairy = Spicy - served medium spicy unless otherwise requested *Images intended for reference only; dishes may not come out exactly as shown. *Please let your server know if you have any food allergies or dietary restrictions. * Consuming raw or undercooked meats, poultry, seafood, shellfish, or eggs may increase your risk of foodborne illness. A1. Fried Eggrolls (Chả Giò) | 5.95 minced filling rolled in a crispy wrapper and deep fried until golden brown (4pc per order) shrimp and pork – served with fish sauce vegetable – served with sweet and sour sauce vegan net eggrolls – served with fish sauce A2. Fried Crab Rangoon (Hoành Thánh Chiên) | 5.95 appetizers creamy crab and veggie dumplings deep fried in a crispy golden wonton wrapper (8pcs per order) A3. Summer Rolls (Gỏi Cuốn) | 4.95 fresh rice paper rolls served cold with noodles, lettuce, mint, and a side of our delicious peanut sauce (2pcs per order) add avocado for 1.00 shrimp (tôm) grilled pork patties (nem nướng) shrimp and pork patty combo (tôm & nem nướng) A4. Dumplings (Sủi Cảo) | 5.95 savory steamed or fried dumplings with your choice of veggie or meat filling and a side of our tangy homemade dumpling sauce (8pcs per order) A5. Fried Chicken Wings (Cánh Gà) | 6.95 crispy wings served with a side of house spicy mayo (6pcs per order) A6. Crispy Squid (Mực Chiên Dòn) | 6.95 beautiful golden rings of squid deep fried in a crispy panko batter and served with a side of our homemade sweet and sour or spicy mayo (10 pcs per order) A7. -

Soup Recipes

Soup Recipes Collection of Easy to Follow Soup Recipes Compiled by Amy Tylor Ebook with Master Resale and Redistribution Rights!! Legal Notice :- You have full rights to sell or distribute this document. You can edit or modify this text without written permission from the compiler. This Ebook is for informational purposes only. While every attempt has been made to verify the information provided in this recipe Ebook, neither the author nor the distributor assume any responsibility for errors or omissions. Any slights of people or organizations are unintentional and the Development of this Ebook is bona fide. This Ebook has been distributed with the understanding that we are not engaged in rendering technical, legal, accounting or other professional advice. We do not give any kind of guarantee about the accuracy of information provided. In no event will the author and/or marketer be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, consequential or other loss or damage arising out of the use of this document by any person, regardless of whether or not informed of the possibility of damages in advance. Contents Contents • All about soups • Value of soup in the meal • General classes of soup. • Classes of soup denoting consistency. • Classes of soups denoting quality • Stock for soup and its uses • Varieties of stock • Additional uses of stock. • Soup extracts • The stockpot - nature, use and care of stockpot. • Flavoring stock. • Making of soup. • Principal ingredients. • Meat used for soup making • Herbs and vegetables used for soup making. • Processes involved in making stock. • Cooking meat for soup. • Removing grease from soup. • Clearing soup. -

Healing & Easy Eats

Healing & Easy Eats Recipes for Head and Neck Cancer Patients & Survivors Official Cookbook Second Edition Healing & Easy Eats Recipes for Head and Neck Cancer Patients & Survivors Head and Neck Cancer Alliance Official Cookbook Second Edition Copyright © 2018 by Head and Neck Cancer Alliance All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. Recipes were provided by families and/or survivors of head and neck cancer and cannot be distributed or reproduced without our consent. FISH & SEAFOOD Fish & Seafood Acorn Squash Soup with Shredded Shrimp 99 Breadfruit Tuna Patties 100 Easy Oven Broiled Salmon Dilly 100 George’s She Crab Soup 101 Greek Fish Stew 102 with Black Mussels & Fresh Rosemary Lobster Bisque 103 Mexican Fish & Okra Soup with Tomatillos 104 Moist Poached Salmon 105 Poached Salmon with Hollandaise Sauce 105 Portuguese Seafood Stew 106 (Sopa Leao Vellosa) Russian Clam Chowder 107 Salmon in Dill Sauce 108 Stir-Fried Luffa Squash 109 with Diced Shrimp & Garlic West Indian Callaloo Soup 110 with Lobster Meat White Asparagus Soup 111 with Back Fin Crab Meat & Yuzu Juice 98 Acorn Squash Soup with Shredded Shrimp 4 acorn squashes 1. Cut squash in half lengthwise and remove seeds. Brush a non-stick baking pan with olive 3 carrots diced oil. Place the squash, cut side down on the pan 1 sweet onion diced and bake for 30 minutes at 350°F. Spoon pulp from squash to create a serving bowl. -

The American Racial Diet

EDIBLE THOUGHTS THE AMERICAN RACIAL DIET SPRING 2019 1 7 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A cookoff is impossible without help. So is a cookbook. We’d like to extend a very special thanks to the following people and communities that came together to make this possible: —The staff who clean and maintain every inch and corner of Princeton University, and work the longest hours to keep the University running. Without them, nothing would be possible. —The Princeton Dining Services staff who were on-call for the entire event and made sure all the hot dishes were hot, cold dishes cold, and cleaned up after the festivities were completed. —The Friend Center staff who worked with us to organize the event, opening literal and figurative doors. —Chef Brad Ortega, from Princeton Dining, for serving as a judge in the cookoff and for engaging with each and every dish as seriously as any dish prepared by a fellow chef. —Smitha Haneef, head of Dining Services, for once again working with us to host this event and for taking the time to visit the class and serve as a judge during the cookoff. —Tara Broderick, from the English Department, who did an incalculable amount of planning, double-checking, and organizing. She is the entire reason why we had tables, a location, utensils, and help. —Sarah Malone for her wonderful coverage of the event for the Program in American Studies webpage and for her excellent photography. —Renae C. Hill for the gorgeous photos, many of which are featured here. —Ali, Catie, Dan, Jason, Jenn, Kim, and Mike, our Assistant Instructors, for reading, lecturing, grading, meeting, and conversing with students and their work all semester long. -

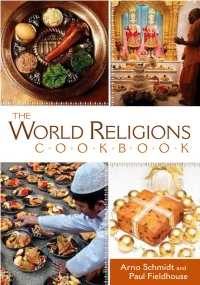

The World Religions Cookbook

THE WORLD RELIGIONS COOKBOOK THE WORLD RELIGIONS COOKBOOK ARNO SCHMIDT AND PAUL FIELDHOUSE Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schmidt, Arno, 1937– The world religions cookbook / Arno Schmidt and Paul Fieldhouse. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–313–33504–4 (alk. paper) 1. Cookery, International. 2. Cookery—Religious aspects. I. Fieldhouse, Paul. II. Title. TX725.A1S42155 2007 641.59—dc22 2007002974 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright C 2007 by Arno Schmidt and Paul Fieldhouse All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007002974 ISBN-13: 978–0–313–33504–4 ISBN-10: 0–313–33504–4 First published in 2007 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 Copyright Acknowledgments The authors and the publisher gratefully acknowledge permission for use of the following material: Illustrations by J. Susan Cole Stone. The publisher has done its best to make sure the instructions and/or recipes in this book are correct. However, users should apply judgment and experience when preparing recipes, especially parents and teachers working with young people. The publisher accepts no responsibility for the outcome of any recipe included in this volume. To Margaret To Corinne, Emma, and Veronica CONTENTS List of Recipes ix Glossary xvii Measurement Conversions xxix Acknowledgments xxxi Introduction xxxiii 1.