The History of Northolt Village

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GUNNERSBURY PARK Options Appraisal

GUNNERSBURY PARK Options Appraisal Report By Jura Consultants and LDN Architects June 2009 LDN Architects 16 Dublin Street Edinburgh EH1 3RE 0131 556 8631 JURA CONSULTANTS www.ldn.co.uk 7 Straiton View Straiton Business Park Loanhead Midlothian Edinburgh Montagu Evans LLP EH20 9QZ Clarges House 6-12 Clarges Street TEL. 0131 440 6750 London, W1J 8HB FAX. 0131 440 6751 [email protected] 020 7493 4002 www.jura-consultants.co.uk www.montagu-evans.co.uk CONTENTS Section Page Executive Summary i. 1. Introduction 1. 2. Background 5. 3. Strategic Context 17. 4. Development of Options and Scenarios 31. 5. Appraisal of Development Scenarios 43. 6. Options Development 73. 7. Enabling Development 87. 8. Preferred Option 99. 9. Conclusions and Recommendations 103. Appendix A Stakeholder Consultations Appendix B Training Opportunities Appendix C Gunnersbury Park Covenant Appendix D Other Stakeholder Organisations Appendix E Market Appraisal Appendix F Conservation Management Plan The Future of Gunnersbury Park Consultation to be conducted in the Summer of 2009 refers to Options 1, 2, 3 and 4. These options relate to the options presented in this report as follows: Report Section 6 Description Consultation Option A Minimum Intervention Option 1 Option B Mixed Use Development Option 2 Option C Restoration and Upgrading Option 4 Option D Destination Development Option 3 Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction A study team led by Jura Consultants with LDN Architects and Montagu Evans was commissioned by Ealing and Hounslow Borough Councils to carry out an options appraisal for Gunnersbury Park. Gunnersbury Park is situated within the London Borough of Hounslow and is unique in being jointly owned by Ealing and Hounslow. -

30Hr Childcare: Analysis of Potential Demand and Sufficiency in Ealing

30hr Childcare: Analysis of potential demand and sufficiency in Ealing. Summer 2016 Introduction: Calculating the number of eligible children in each Ward of the borough The methodology utilised by the DfE to predict the number of eligible children in the borough cannot be replicated at Ward level (refer to page 14: Appendix 1 for DfE methodology) Therefore the calculations for the borough have been calculated utilising the most recent data at Ward level concerning the proportions of parents working, the estimates of 3& 4 year population and the number of those 4yr old ineligible as they are attending school. The graph below illustrates the predicted lower and upper estimates for eligible 3&4 year olds for each Ward Page 1 of 15 Executive Summary The 30hr eligibility criteria related to employment, income and the number of children aged 4 years attending reception class (who are ineligible for the funding) makes it much more likely that eligible children will be located in Wards with higher levels of employment and income (potentially up to a joint household income of £199,998) and lower numbers of children aged 4years in reception class. Although the 30hr. childcare programme may become an incentive to work in the future, in terms of the immediate capital bid, the data points to investment in areas which are quite different than the original proposal, which targeted the 5 wards within the Southall area. The 5 Southall Wards are estimated to have the fewest number of eligible children for the 30hr programme. The top 5 Wards estimated to have the highest number of eligible children are amongst the least employment and income deprived Wards in Ealing with the lowest numbers of children affected by income deprivation. -

2021 First Teams - Premier Division Fixtures

2021 First Teams - Premier Division Fixtures Brondesbury vs. North Middlesex North Middlesex vs. Brondesbury Sat. 8 May Richmond vs. Twickenham Sat. 10 July Twickenham vs. Richmond Overs games Teddington vs. Ealing Time games Ealing vs. Teddington 12.00 starts Crouch End vs. Shepherds Bush 11.00 starts Shepherds Bush vs. Crouch End Finchley vs. Hampstead Hampstead vs. Finchley Shepherds Bush vs. Richmond Richmond vs. Shepherds Bush Sat. 15 May Ealing vs. Brondesbury Sat. 17 July Brondesbury vs. Ealing Overs games North Middlesex vs. Finchley Time games Finchley vs. North Middlesex 12.00 starts Twickenham vs. Teddington 11.00 starts Teddington vs. Twickenham Hampstead vs. Crouch End Crouch End vs. Hampstead Brondesbury vs. Teddington Teddington vs. Brondesbury Sat. 22 May Richmond vs. Hampstead Sat. 24 July Hampstead vs. Richmond Overs games Crouch End vs. North Middlesex Time games North Middlesex vs. Crouch End 12.00 starts Finchley vs. Ealing 11.00 starts Ealing vs. Finchley Twickenham vs. Shepherds Bush Shepherds Bush vs. Twickenham Brondesbury vs. Finchley Finchley vs. Brondesbury Sat. 29 May Teddington vs. Shepherds Bush Sat. 31 July Shepherds Bush vs. Teddington Overs games Ealing vs. Crouch End Time games Crouch End vs. Ealing 12.00 starts North Middlesex vs. Richmond 11.00 starts Richmond vs. North Middlesex Hampstead vs. Twickenham Twickenham vs. Hampstead Richmond vs. Ealing Ealing vs. Richmond Sat. 5 June Shepherds Bush vs. Hampstead Sat. 7 August Hampstead vs. Shepherds Bush Overs games Crouch End vs. Brondesbury Time games Brondesbury vs. Crouch End 12.00 starts Finchley vs. Teddington 11.00 starts Teddington vs. Finchley Twickenham vs. -

Northalla Fields Management Plan Northala Fields

Northala Fields Management & Maintenance Plan 2020 - 2025 Issue number: 1 Status: FINAL Date: 21 January 2020 Prepared by: Vanessa Hampton and Mark Reynolds Authorised by: Chris Welsh Reviewed by: Mark Reynolds CFP • The Coach House • 143 - 145 Worcester Road • Hagley • Worcestershire • DY9 0NW t: 01562 887884 • f: 01562 887087 • e: [email protected] • w: cfpuk.co.uk Contents Introduction............................................................................................... 6 About the Plan ................................................................................................................ 6 Management Vision ......................................................................................................... 7 Site Details and Context ............................................................................ 8 Location ......................................................................................................................... 8 Site Description .............................................................................................................. 8 2.2.1. Zone 1 – The Mounds ........................................................................................... 13 2.2.2. Zone 2 – Play areas and Avenue ............................................................................ 13 2.2.3. Zone 3 – Ponds, wetland and visitor centre ............................................................ 13 2.2.4. Zone 4 – Southern Meadow and other habitat areas .............................................. -

Policies Map Booklet

Policies Map Booklet 29th June 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Map Sheet Corresponding Schedules 1 OPEN SPACE 1 Green Belt 2 Metropolitan Open Land 3 Public Open Space (Including Proposed POS) 4 Community Open Space 2 DEFICIENCY MAPPING – LOCAL/DISTRICT NA 3 DEFICIENCY MAPPING – METROPOLITAN NA 4 NATURE CONSERVATION 5 Sites of Metropolitan, Borough and Local Importance 5 ANCIENT MONUMENTS AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL INTEREST AREAS 6 Ancient Monuments 6 Archaeological Interest Ares 6 INDUSTRIAL LOCATIONS 7 Strategic Industrial Locations & Locally Significant Sites 7 SHOPPING AND TOWN CENTRES 8 Town Centres 8 Shopping Frontages 8 VIEWS AND LANDMARKS 9 Local Viewpoints 9 Landmarks Development Sites DPD Final Proposals Consultation June 2012 i This page has been left intentionally blank ii Development Sites DPD Final Proposals Consultation June 2012 INTRODUCTION What is the Policies Map? Covering the whole borough, the Policies Map (formerly the Proposals Map DPD) will show geographically all land use policies set out in the adopted DPDs. In this regard it will: • identify areas of protection, such as Green Belt and nature conservation sites, defined through the development plan process. • Allocate sites for particular land use and development proposals included in any adopted development plan document, and set out the areas to which specific policies apply. Whilst the Policies Map is a separate Development Plan Document in its own right, it essentially forms the graphical representations of the other Development Plan Documents. The Policies Map comprises a large scale map sheet (approximately A0 size), prepared on an Ordnance Survey base, at a scale which is sufficient to allow the policies and proposals to be clearly illustrated. -

Neighbourly Care Free Weekly Exercise Classes

330-332 Ruislip Road Telephone: 0208 571 1929 Northolt Email: [email protected] Neighbourly Care Web-site: www.neighbourlycare.org.uk UB5 6BG Facebook: Neighbourly Care NEIGHBOURLY CARE FREE WEEKLY EXERCISE CLASSES Staying physically active Keeping physically active improves your health and quality of life, and can also help you to live longer. It's never too late to start doing some exercise. Health benefits The best type of activity is one that makes you feel slightly warmer and breathe a bit heavier, getting your heart and pulse pumping faster than usual. Some of the benefits of keeping active include: • a reduced risk of developing a life-threatening disease and a greater sense of well-being • improved sleep, increased day-time vitality and staying independent • having a healthier heart and reducing falls • meeting people and sharing the company of others • feeling happier, keeping your brain sharp and ageing better Neighbourly Care runs weekly exercise classes—free of charge—across the borough. They are friendly and fun but led by qualified instructors and designed to benefit older people. The sessions last for between 30-45 minutes and afterwards you can relax and enjoy the other activities offered at our hubs—talks, games, conversation, companionship. tea and coffee, arts and crafts groups. If you would like more details and/or further information please contact Nurita Bangar (Neighbourly Care Health Services Officer) on 0208 571 1929 or at [email protected]. EVERY MONDAY Ruskin Hall, Church Road, Acton, -

Ealing Civic Society Newsletter – Autumn 2011

Autumn 2011 Chairman’s Message Thank you to all who made it out to the Northala Fields with the development prior to initiating compulsory pur - event in June. Despite uncertain weather those who at - chase procedures in October. Somewhat to everyone's sur - tended seemed to enjoy the talks and the guided walk prise the chief executive of Empire Cinemas, Justin around the mounds. Ribbons, accepted the Council's invitation to appear before Local Listing the Overview & Scrutiny committee in late July. He said On Civic Day (25 June) we launched the "spot your local that the latest delay was caused by the fact that they gems" campaign which wanted to incorpo - seems to have caught peo - In common with all who live in and care about Ealing, we were rate an IMAX screen ple's imagination and we shocked by the recent vandalism and damage to the town centre. into the develop - have had many interesting The Council (with some public-spirited members of the commu - ment which they be - buildings nominated for nity) acted with commendable speed over the short-term clear up lieved only needed a local listing. There is still but it will take time to heal the scars. The Government, Mayor non-material time to nominate a building Johnson and London councils need to act together to ensure that amendment to the or structure – go to our web - there is no repetition of the events which led to the tragic loss of existing planning site for more details. The life, livelihoods, shops and homes and which have proved to be so permission but this Council has taken the local threatening to both the moral and physical fabric of our society. -

Appendix 1 Ealing Heritage Strategy Draft 2010

Appendix 1 Ealing Heritage Strategy Draft 2010 - 2015 1 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Ealing’s Heritage 3. National and local context 4. Ealing’s Heritage: issues and opportunities 5. A new vision for Ealing’s Heritage, Objectives & Delivery Plan 2 1. Introduction 1.1 Ealing has a rich and deep built, natural and material heritage highly valued by residents. As with most councils responsibility for managing and promoting the borough’s heritage is divided amongst council departments. The Executive Director for Environment and Customer Services is responsible for the strategic lead for heritage development and is responsible for the management of important built, natural and material heritage assets. There are further responsibilities including planning, conservation, regeneration and ownership of some heritage assets which sit across the council. 1.2 The development of a sustainable future for key heritage assets has become a higher priority for the council over recent years and it is now necessary to adopt a strategic approach to this area of activity. The heritage strategy is intended to have the following benefits: a framework for maximising investment in Ealing’s heritage set a direction and define priorities within and between heritage initiatives and reconcile competing demands inform the management of the Council’s assets, detailed service plans and the work of individual officers, departments and other agencies encourage innovation and improved partnership working act as a lever and rationale for gaining funding from external agencies and partners demonstrate links with the long term vision for Ealing, central government agendas and with strategies of national and regional agencies 1.3 There are many definitions of heritage in the public domain including built, natural and material elements. -

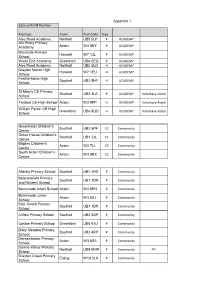

Appendix 1 Sites with Dfe Number Premises Town Post Code Type

Appendix 1 Sites with DfE Number Premises Town Post Code Type Alec Reed Academy Northolt UB5 5LP P ACADEMY Ark Priory Primary Academy Acton W3 8NY P ACADEMY Brentside Primary Hanwell W7 1JL P ACADEMY School Wood End Academy Greenford UB6 0EQ P ACADEMY Alec Reed Academy Northolt UB5 5LQ H ACADEMY Drayton Manor High Hanwell W7 1EU H ACADEMY School Featherstone High Southall UB2 5HF H ACADEMY School St Mary's CE Primary Southall UB2 4LA P ACADEMY Voluntary-Aided School Twyford CE High School Acton W3 9PP H ACADEMY Voluntary-Aided William Perkin CE High Greenford UB6 8QD H ACADEMY Voluntary-Aided School Greenfields Children's Southall UB2 5PF CC Community Centre Grove House Children's Southall UB1 2JL CC Community Centre Maples Children's Acton W3 7LL CC Community Centre South Acton Children's Acton W3 8RX CC Community Centre Allenby Primary School Southall UB1 2HX P Community Beaconsfield Primary Southall UB1 1DR P Community and Nursery School Berrymede Infant School Acton W3 8RN P Community Berrymede Junior Acton W3 8SJ P Community School Blair Peach Primary Southall UB1 1DR P Community School Clifton Primary School Southall UB2 5QP P Community Coston Primary School Greenford UB6 9JU P Community Dairy Meadow Primary Southall UB2 4RP P Community School Derwentwater Primary Acton W3 6SA P Community School Downe Manor Primary Northolt UB5 6NW P Community PFI School Drayton Green Primary Ealing W13 0LA P Community School Premises Town Post Code Type Durdans Park Primary Southall UB1 2PQ P Community School East Acton Primary Acton W3 7HA P Community -

10.3 Green Corridors See Policy 3.2 and Map Sheets 1, 2 and 15

Ealing’s Adopted 2004 Plan for the Environment / DCLG Direction 2007 Chapter Ten 10.3 Green Corridors See Policy 3.2 and Map Sheets 1, 2 and 15 1. Western Avenue A40 The greening of this important transport route from the western boundary of the borough along the A40 to Park Royal station (linking Major Open Areas and branching northwards along Horsenden Lane South) and extending to the borough boundary at East Acton on land originally acquired for road widening. Along the A40, the road and footway/cycleway will be separated by landscaping and mounding where possible, and improvement made to the landscaping of the boundaries of the corridor. 2. North Circular Road NW10 and W5 Where it links Major Open Areas between Twyford Abbey, Hanger Hill Park, Ealing Common and Gunnersbury Park. The road and footway/cycleway will be separated by landscaping where possible, and improvements made to the landscaping of the boundaries of the corridor. The area of the former road improvement line is retained as Green Corridor and all of Gunnersbury Ave is now included. 3. Grand Union Canal Including the towpath, associated land and small related areas. This is also defined as a Green Chain and as a nature conservation Site of Metropolitan Importance by the London Ecology Unit. 4. Ruislip Road Northolt From Down Barns to Rectory Park where landscaping of the Hayes By-pass extends the corridor southwards. 5. Greenford Branch Line Including embankment and adjoining uses from Greenford Station Viaduct through Perivale Park in the Brent River Park to the junction with the London to Swansea main line (see 12d). -

Hounslow West Hatton Cross Northolt South Ruislip

Epping Chesham Watford Junction Enfield Town Chalfont & Theydon Bois Latimer 5 Watford High Street 5 Watford High Barnet Cockfosters Debden Bush Hill Turkey street Amersham Bushey Park Chorleywood Croxley 6 Totteridge & Whetstone Oakwood Loughton 6 Carpenders Park Southbury Buckhurst Hill Rickmansworth Moor Park Woodside Park Southgate Chingford Roding Grange Hatch End Northwood Mill Hill East West Finchley Valley Hill 5 Arnos Grove West Ruislip Northwood Edgware Hills Headstone Lane Stanmore 4 Bounds Green Chigwell Hillingdon Ruislip Harrow & Burnt Oak Finchley Central Hainault Ruislip Manor Pinner Wealdstone Canons Park Wood Green Woodford Harold Wood Uxbridge Ickenham Colindale East Finchley Fairlop Eastcote North Harrow Kenton Harringay South Woodford Queensbury Turnpike Lane Green Lanes Gidea Park 4 Barkingside Northwick Hendon Central Crouch Harrow- Preston Highgate South Tottenham on-the-Hill Park Road Kingsbury Hill Snaresbrook Romford Ruislip Rayners Lane Brent Cross Newbury Park Gardens Seven Blackhorse Gospel Sisters 3 Road Redbridge West South Kenton Golders Green Oak Harrow Hampstead Upper Holloway Chadwell Emerson Park South Harrow Neasden Heath Tottenham Walthamstow Heath North Wembley Wanstead Gants South Ruislip Wembley Arsenal Hale Central Dollis Hill Tufnell Park Finsbury Hill Goodmayes Wembley Central Park Park Leytonstone Finchley Road Holloway Road Walthamstow Leyton Leytonstone Seven Kings Sudbury Hill Stonebridge Park & Frognal Kentish Upminster Town West Kentish Town Queen’s Road Midland Road High Road Ilford Belsize Park Upminster Kilburn Northolt Harlesden Kensal Brondesbury Caledonian Road Highbury & Dalston Manor Park Bridge Sudbury Town Rise Park Islington Kingsland Leyton Dagenham Hornchurch West Hampstead Chalk Farm Camden East Hackney Stratford Elm Park Road 3International Finchley Road Camden Town Central Wanstead Park Kensal Green Brondesbury Caledonian Road & Canonbury Alperton Swiss Cottage 2 Kilburn South Barnsbury Dagenham Queen’s Park Dalston Junction Stratford High Road Hampstead St. -

Early Years Settings Contacts List

Early years settings contacts list Academy Gardens Children's Centre Acton Park Children's Centre 1 Academy Garden Acton Park Northolt, UB5 5QN Acton, W3 7LJ Tel: 020 8842 0220 Tel: 020 8743 6133 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Copley Close Children's Centre Dormers Wells Children's Centre 363 Copley Close Dormers Wells Lane Hanwell, W7 1QG Southall, UB1 3HX Tel: 020 8566 6260 Tel: 020 8574 1200 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Ealing Hospital Children's Centre Grange Children's Centre Uxbridge Road Church Gardens Southall, UB1 3HW Ealing, W5 4HN Tel: 020 8967 5478 Tel: 020 8567 1135 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Greenfields Children's Centre Grove House Children's Centre Recreation Road 77a North Road Southall, UB2 5PF Southall, UB1 2JG DfE No: 307/1007 DfE No: 307/1002 Head of centre: Ellie Larkin Head of centre: Himisha Patel Tel: 020 8813 8079 Tel: 020 8571 0878 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.greenfieldschildren.com Website: http://www.grovehousecc.com Hanbury Nursery Hanwell Children's Centre Park Road North 25a Laurel Gardens London, W3 8RX Hanwell, W7 3JG Tel: (020) 8993 9075 Tel: 020 8825 8200 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Hathaway Children's Centre Havelock Children's Centre Hathaway Gardens 17 Trubshaw Road Ealing, W13 0DH Southall, UB2 4XW Tel: 020 8998 8903 Tel: 020 8571 1219 Email: [email protected]