Acute and Chronic Mediastinitis Julius Dean Yale University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Study of Pneumomediastinums Based on Clinical Experience

ORIGINAL ARTICLE A comparative study of pneumomediastinums based on clinical experience Ersin Sapmaz, M.D.,1 Hakan Işık, M.D.,1 Deniz Doğan, M.D.,2 Kuthan Kavaklı, M.D.,1 Hasan Çaylak, M.D.1 1Department of Thoracic Surgery, Gülhane Training and Research Hospital, Ankara-Turkey 2Department of Pulmonology, Gülhane Training and Research Hospital, Ankara-Turkey ABSTRACT BACKGROUND: Pneumomediastinum (PM) is the term which defines the presence of air in the mediastinum. PM has also been described as mediastinal emphysema. PM is divided into two subgroups called as Spontaneous PM (SPM) and Secondary PM (ScPM). METHODS: A retrospective comparative study of the PM diagnosed between February 2010 and July 2018 is presented. Forty patients were compared. Clinical data on patient history, physical characteristics, symptoms, findings of examinations, length of the hospital stay, treatments, clinical time course, recurrence and complications were investigated carefully. Patients with SPM, Traumatic PM (TPM) and Iatrogenic PM (IPM) were compared. RESULTS: SPM was identified in 14 patients (35%). In ScPM group, TPM was identified in 16 patients (40%), and IPM was identified in 10 patients (25%). On the SPM group, the most frequently reported symptoms were chest pain, dyspnea, subcutaneous emphysema and cough. CT was performed to all patients to confirm the diagnosis and to assess the possible findings. All patients prescribed pro- phylactic antibiotics to prevent mediastinitis. CONCLUSION: The present study aimed to evaluate the clinical differences and managements of PMs in trauma and non-trauma patients. The clinical spectrum of pneumomediastinum may vary from benign mediastinal emphysema to a fatal mediastinitis due to perforation of mediastinal structures. -

Tuberculosis Mediastinal Fibrosis Misdiagnosed As Chronic Bronchitis for 10 Years: a Case Report

1183 Letter to the Editor Tuberculosis mediastinal fibrosis misdiagnosed as chronic bronchitis for 10 years: a case report Wei-Wei Gao, Xia Zhang, Zhi-Hao Fu,Wei-Yi Hu, Xiang-Rong Zhang, Guang-Chuan Dai, Yi Zeng Department of Tuberculosis of Three, Nanjing Public Health Medical Center, Nanjing Second Hospital, Nanjing Hospital Affiliated to Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Nanjing 211132, China Correspondence to: Dr. Yi Zeng. Department of Tuberculosis of Three, Nanjing Public Health Medical Center, Nanjing Second Hospital, Nanjing Hospital Affiliated to Nanjing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, No. 1, Kangfu Road, Nanjing 211132, China. Email: [email protected]. Submitted Feb 27, 2019. Accepted for publication Jun 19, 2019. doi: 10.21037/qims.2019.06.13 View this article at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/qims.2019.06.13 Background over previous 2 months. All vital signs at presentation were normal (temperature: 37.6 , heart rate: 97/min, blood Mediastinal fibrosis (MF, or fibrosing mediastinitis) is a rare pressure: 155/95 mmHg, saturation: 95%). Clinical physical condition characterized by rapid increase of fibrous tissues in ℃ examination revealed a lip purpura and reduced breath the mediastinum and is often associated with granulomatous sound in the right lung. diseases such as histoplasmosis, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, and other fibroinflammatory and autoimmune diseases (1-3). It can cause compression and obliteration of vital mediastinal Laboratory tests structures, e.g., trachea, esophagus, and great vessels (4,5). Blood test results were as follows: blood cell count and Given that the disease is rare and its clinical symptoms liver and kidney function normal. -

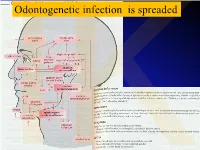

Anatomical Overview

IKOdontogenetic infection is spreaded Možné projevy zlomenin a zánětů IKPossible signs of fractures or inflammations Submandibular space lies between the bellies of the digastric muscles, mandible, mylohyoid muscle and hyoglossus and styloglossus muscles IK IK IK IK IK Submandibulární absces Submandibular abscess IK Sběhlý submandibulární absces Submandibular abscess is getting down IK Submental space lies between the mylohyoid muscles and the investing layer of deep cervical fascia superficially IK IK Spatium peritonsillare IK IK Absces v peritonsilární krajině Abscess in peritonsilar region IK Fasciae Neck fasciae cervicales Demarcate spaces • fasciae – Superficial (investing): • f. nuchae, f. pectoralis, f. deltoidea • invests m. sternocleidomastoideus + trapezius • f. supra/infrahyoidea – pretrachealis (middle neck f.) • form Δ, invests infrahyoid mm. • vagina carotica (carotic sheet) – Prevertebral (deep cervical f.) • Covers scaleni mm. IK• Alar fascia Fascie Fascia cervicalis superficialis cervicales Fascia cervicalis media Fascia cervicalis profunda prevertebralis IKsuperficialis pretrachealis Neck spaces - extent • paravisceral space – Continuation of parafaryngeal space – Nervous and vascular neck bundle • retrovisceral space – Between oesophagus and prevertebral f. – Previsceral space – mezi l. pretrachealis a orgány – v. thyroidea inf./plx. thyroideus impar • Suprasternal space – Between spf. F. and pretracheal one IK– arcus venosus juguli 1 – sp. suprasternale suprasternal Spatia colli 2 – sp. pretracheale pretracheal 3 – -

Mediastinitis and Bilateral Pleural Empyema Caused by an Odontogenic Infection

Radiol Oncol 2007; 41(2): 57-62. doi:10.2478/v10019-007-0010-0 case report Mediastinitis and bilateral pleural empyema caused by an odontogenic infection Mirna Juretic1, Margita Belusic-Gobic1, Melita Kukuljan3, Robert Cerovic1, Vesna Golubovic2, David Gobic4 1Clinic for Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 2Clinic for Anaesthesiology and Reanimatology, 3Department of Radiology, 4Clinic for Internal Medicine, Clinical hospital, Rijeka, Croatia Background. Although odontogenic infections are relatively frequent in the general population, intrathoracic dissemination is a rare complication. Acute purulent mediastinitis, known as descending necrotizing mediastin- itis (DNM), causes high mortality rate, even up to 40%, despite high efficacy of antibiotic therapy and surgical interventions. In rare cases, unilateral or bilateral pleural empyema develops as a complication of DNM. Case report. This case report presents the treatment of a young, previously healthy patient with medias- tinitis and bilateral pleural empyema caused by an odontogenic infection. After a neck and pharynx re-inci- sion, and as CT confirmed propagation of the abscess to the thorax, thoracotomy was performed followed by CT-controlled thoracic drainage with continued antibiotic therapy. The patient was cured, although the recognition of these complications was relatively delayed. Conclusions. Early diagnosis of DNM can save the patient, so if this severe complication is suspected, thoracic CT should be performed. Key words: mediastinitis; empyema, pleural; periapical abscess – complications Introduction rare complication of acute mediastinitis.1-6 Clinical manifestations of mediastinitis are Acute suppurative mediastinitis is a life- frequently nonspecific. If the diagnosis of threatening infection infrequently occur- mediastinitis is suspected, thoracic CT is ring as a result of the propagation of required regardless of negative chest X-ray. -

MSS 1. a Patient Presented to a Traumatologist with a Trauma Of

MSS 1. A patient presented to a traumatologist with a trauma of shoulder. What wall of axillary cavity contains foramen trilaterum and foramen quadrilaterum? a) anterior b) posterior c) lateral d) medial e) intermediate 2. A patient presented to a traumatologist with a trauma of leg, which he had sustained at a sport competition. Upon examination, damage of posterior muscle, that is attached to calcaneus by its tendon, was found. This muscle is: a) triceps surae b) tibialis posterior c) popliteus d) fibularis longus e) fibularis brevis 3. In the course of a cesarean section, an incision was made in the pubic area and vagina of rectus abdominis muscle was cut. What does anterior wall of the vagina of rectus abdominis muscle consist of? A. aponeurosis of m. transversus abdominis, m. obliquus internus abdominis. B. aponeurosis of m. transversus abdominis, m. pyramidalis. C. aponeurosis of m. obliquus internus abdominis, m. obliquus externus abdominis. D. aponeurosis of m. transversus abdominis, m. obliquus externus abdominis. E. aponeurosis of m. transversus abdominis, m. obliquus internus abdominis 4. A 30 year-old woman complained of pain in the lower part of her forearm. Traumatologist found that her radio-carpal joint was damaged. This joint is: A. complex, ellipsoid B.simple, ellipsoid C.complex, cylindrical D.simple, cylindrical E.complex condylar 5. A woman was brought by an ambulance to the emergency department with a trauma of the cervical part of her vertebral column. Radiologist diagnosed a fracture of a nonbifid spinous processes of one of her cervical vertebrae. Spinous process of what cervical vertebra is fractured? A.VI. -

Fibrosing Mediastinitis, Severe Pulmonary Hypertension, And

Vascular Diseases and Therapeutics Case Report ISSN: 2399-7400 Troublesome triad: fibrosing mediastinitis, severe pulmonary hypertension, and pulmonary vein stenosis Gregory W Wigger*1 and Jean Elwing2 1Resident Physician, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Cincinnati Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH 45267, USA 2Associate Professor of Medicine, Department of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, University of Cincinnati Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH 45267, USA Abstract Fibrosing mediastinitis is a disorder of invasive and proliferative fibrous tissue growth in the mediastinum. Its occurrence is rare and cause unknown, though it has been associated with several infections. The fibrosis of mediastinal structures, particularly vasculature, results in common symptoms of cough, dyspnea and hemoptysis due to pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary edema, and parenchyma fibrosis. Progression of disease carries a high mortality rate and causes of death are typically due to cor pulmonale,pulmonary infections and respiratory failure. Several medical treatments and surgical procedures have been unsuccessful; however the use of endovascular stenting is showing promising results. Early recognition and diagnosis are essential to provide patients with the best chance of survival and management options.We review the case of a 43 year-old female diagnosed with fibrosing mediastinitis and sequelae of pulmonary vein stenosis and pulmonary hypertension. Unfortunately, she was a poor candidate for pulmonic vein stenting due to her unstable condition. Without treatment of the stenosis, her clinical status and pulmonary hypertension worsened. Pulmonary vasodilators resulted in pulmonary edema and diuresis resulted in hypotension. Ultimately her condition was untreatable. This case illustrates the devastating effects of advanced fibrosing mediastinitis. Clinical presentation/Course The patient’s family elected to withdraw care and the patient passed after extubation. -

Esophageal Perforation by a Sengstaken Balloon

1130-0108/2017/109/5/371 REVISTA ESPAÑOLA DE ENFERMEDADES DIGESTIVAS REV ESP ENFERM DIG © Copyright 2017. SEPD y © ARÁN EDICIONES, S.L. 2017, Vol. 109, N.º 5, pp. 371 PICTURES IN DIGESTIVE PATHOLOGY Esophageal perforation by a Sengstaken balloon Antonio José Fernández-López, María Encarnación Tamayo-Rodríguez, Francisco Miguel González-Valverde and Antonio Albarracín-Marín-Blázquez Department of Surgery. Hospital General Reina Sofía. Murcia, Spain CASE REPORT A 55-year-old patient presented with ethanolic cirrhosis A B (CHILD B9) and hemodynamic instability (heart rate: 112 bpm, blood pressure: 83/62) from massive upper gastroin- testinal bleeding (UGIB). Upper gastrointestinal endosco- py (UGIE) revealed active bleeding from esophageal var- ices. As sclerotherapy and band ligation failed to provide hemostasis; the decision was made to use a Sengstaken balloon (SB). The balloon was insufflated with 300 ml for the gastric channel and 200 ml for the esophageal chan- nel. X-rays after insufflation showed the gastric balloon at the distal esophagus. A repeat UGIE procedure showed a laceration at the lower third of the esophagus. A CT scan Fig. 1. A. Pneumomediastinum from esophageal perforation. B. Left revealed pneumomediastinum (Fig. 1A). Given his clini- posterolateral longitudinal esophageal tear. cal instability, the patient was operated on immediately, and an 8-cm longitudinal esophageal rupture was found in the lower third (Fig. 1B), which underwent primary suture repair. She died after five days from hepatorenal syndrome. Surgery is the treatment of choice for esophageal rup- ture. Conservative endoscopic management with Ovesco clips and self-expandable stents has been described for DISCUSSION smaller tears (< 10 mm) in the absence of sepsis (3). -

Esophageal Perforations: New Perspectives and Treatment Paradigms James T

Review Article The Journal of TRAUMA Injury, Infection, and Critical Care Esophageal Perforations: New Perspectives and Treatment Paradigms James T. Wu, MD, Kenneth L. Mattox, MD, and Matthew J. Wall Jr, MD Despite significant advances in mod- ever, less invasive approaches to esophageal attempt to summarize the pathogenesis ern surgery and intensive care medicine, perforation continue to evolve. As the inci- and diagnostic evaluation of esophageal esophageal perforation continues to present dence of esophageal perforation increases injuries, and highlight the evolving thera- a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Con- with the advancement of invasive endo- peutic options for the management of troversies over the diagnosis and manage- scopic procedures, early recognition of esophageal perforation. ment of esophageal perforation remain, and clinical features and implementation of Key Words: Esophageal trauma, debate still exists over the optimal therapeu- effective treatment are essential for a fa- Esophageal perforation, Minimally inva- tic approach. Surgical therapy has been the vorable clinical outcome with minimal sive thoracoscopic surgery, Esophageal traditional and preferred treatment; how- morbidity and mortality. This review will stenting, Esophageal endoclipping. J Trauma. 2007;63:1173–1184. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY injuries to the esophagus occurred in 4% of patients, and the External Trauma overall mortality rate was 19%.5 enetrating esophageal trauma occurs mainly in the cer- Esophageal perforation from external blunt trauma is an vical esophagus, and morbidity is usually associated exceedingly rare event. The most common cause is related to 6–9 Pwith vascular, tracheal, and spinal cord injuries.1,2 high-speed motor vehicle crashes. Beal et al. examined 96 Hirshberg et al. evaluated 34 patients with transcervical gun- reported cases of blunt esophageal trauma, and found that the shot wounds, and found 2 patients (6%) with esophageal site of perforation occurred in the cervical and upper thoracic 10 injuries.1 Similarly, Demetriades et al. -

Treatment of Spontaneous Esophageal Rupture (Boerhaave Syndrome) Using Thoracoscopic Surgery and Sivelestat Sodium Hydrate

2212 Original Article Treatment of spontaneous esophageal rupture (Boerhaave syndrome) using thoracoscopic surgery and sivelestat sodium hydrate Hiroshi Okamoto1, Ko Onodera2, Rikiya Kamba3, Yusuke Taniyama1, Tadashi Sakurai1, Takahiro Heishi1, Jin Teshima1,4, Makoto Hikage1,5, Chiaki Sato1, Shota Maruyama1, Yu Onodera1, Hirotaka Ishida1, Takashi Kamei1 1Department of Gastroenterological Surgery, Graduate School of Medicine, 2Department of General Practitioner Development, Graduate School of Medicine, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan; 3Department of Surgery, Osaki Citizen Hospital, Osaki, Japan; 4Department of Surgery, Iwate Prefectural Central Hospital, Morioka, Japan; 5Department of Surgery, Sendai City Hospital, Sendai, Japan Contributions: (I) Conception and design: H Okamoto, T Kamei; (II) Administrative support: T Kamei; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: K Onodera, R Kamba; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: H Okamoto, Y Taniyama, T Sakurai, T Heishi, J Teshima, M Hikage, C Sato, S Maruyama; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: H Okamoto, Y Onodera, H Ishida; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Hiroshi Okamoto, MD, PhD. Department of Gastroenterological Surgery, Graduate School of Medicine, Tohoku University, 1-1 Seiryo-machi, Aoba-ku, Sendai 980-8574, Japan. Email: [email protected]. Background: The mortality rate of spontaneous esophageal rupture remains 20% to 40% due to severe respiratory failure. We have performed thoracoscopic surgery for esophageal disease at our department since 1994. Sivelestat sodium hydrate reportedly improves the pulmonary outcome in the patients with acute lung injury (ALI). Methods: We retrospectively evaluated the usefulness of thoracoscopic surgery and perioperative administration of sivelestat sodium hydrate for spontaneous esophageal rupture in 12 patients who underwent thoracoscopy at our department between 2002 and 2014. -

Boerhaave Syndrome Due to Excessive Alcohol Consumption

Haba et al. International Journal of Emergency Medicine (2020) 13:56 International Journal of https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-020-00318-5 Emergency Medicine CASE REPORT Open Access Boerhaave syndrome due to excessive alcohol consumption: two case reports Yuichiro Haba1,2*, Shungo Yano1, Hikaru Akizuki2, Takashi Hashimoto3, Toshio Naito1 and Naoyuki Hashiguchi2 Abstract Background: Spontaneous esophageal rupture, or Boerhaave syndrome, is a fatal disorder caused by an elevated esophageal pressure owing to forceful vomiting. Patients with Boerhaave syndrome often present with chest pain, dyspnea, and shock. We report on two patients of Boerhaave syndrome with different severities that was triggered by excessive alcohol consumption and was diagnosed immediately in the emergency room. Case presentation: The patient in case 1 complained of severe chest pain and nausea and vomited on arrival at the hospital. He was subsequently diagnosed with Boerhaave syndrome coupled with mediastinitis using computed tomography (CT) and esophagogram. An emergency operation was successfully performed, in which a 3-cm tear was found on the left posterior wall of the distal esophagus. The patient subsequently had anastomotic leakage but was discharged 41 days later. The patient in case 2 complained of severe chest pain, nausea, vomiting, and hematemesis on arrival. He was suggested of having Boerhaave syndrome without mediastinitis on CT. The symptoms gradually disappeared after conservative treatment. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy performed on the ninth day revealed a scar on the left wall of the distal esophagus. The patient was discharged 11 days later. In addition to the varying severity between the cases, the patient in case 2 was initially considered to have Mallory– Weiss syndrome. -

Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine Sumy State University 0

Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine Sumy State University 0 Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine Sumy State University SPLANCHNOLOGY, CARDIOVASCULAR AND IMMUNE SYSTEMS STUDY GUIDE Recommended by the Academic Council of Sumy State University Sumy Sumy State University 2016 1 УДК 611.1/.6+612.1+612.017.1](072) ББК 28.863.5я73 С72 Composite authors: V. I. Bumeister, Doctor of Biological Sciences, Professor; L. G. Sulim, Senior Lecturer; O. O. Prykhodko, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Assistant; O. S. Yarmolenko, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Assistant Reviewers: I. L. Kolisnyk – Associate Professor Ph. D., Kharkiv National Medical University; M. V. Pogorelov – Doctor of Medical Sciences, Sumy State University Recommended for publication by Academic Council of Sumy State University as а study guide (minutes № 5 of 10.11.2016) Splanchnology Cardiovascular and Immune Systems : study guide / С72 V. I. Bumeister, L. G. Sulim, O. O. Prykhodko, O. S. Yarmolenko. – Sumy : Sumy State University, 2016. – 253 p. This manual is intended for the students of medical higher educational institutions of IV accreditation level who study Human Anatomy in the English language. Посібник рекомендований для студентів вищих медичних навчальних закладів IV рівня акредитації, які вивчають анатомію людини англійською мовою. УДК 611.1/.6+612.1+612.017.1](072) ББК 28.863.5я73 © Bumeister V. I., Sulim L G., Prykhodko О. O., Yarmolenko O. S., 2016 © Sumy State University, 2016 2 Hippocratic Oath «Ὄμνυμι Ἀπόλλωνα ἰητρὸν, καὶ Ἀσκληπιὸν, καὶ Ὑγείαν, καὶ Πανάκειαν, καὶ θεοὺς πάντας τε καὶ πάσας, ἵστορας ποιεύμενος, ἐπιτελέα ποιήσειν κατὰ δύναμιν καὶ κρίσιν ἐμὴν ὅρκον τόνδε καὶ ξυγγραφὴν τήνδε. -

Neck Formation and Growth. MAIN TOPOGRAPHIC REGIONS in NECK

Neck formation and growth. MAIN TOPOGRAPHIC REGIONS IN NECK. ANATOMICAL BACKGROUND FOR URGENT LIFE SAVING PERFORMANCES. orofac Ivo Klepáček orofac Vymezení oblasti krku Extent of the neck region Sensitivní oblasti V1, V2, V3., plexus cervicalis orofac * * * * * orofac** * orofac orofac orofaccranial middle caudal orofac orofac Clinical classification of neck lymph nodes orofacClinical classification of neck lymphatic nodes: I - VI Nodi lymphatici out of regiones above: Perifacial, periparotic, retroauricular, suboccipital, retropharyngeal Metastasa v krčních uzlinách Metastasis in cervical orofaclymphonodi TOPOGRAPHIC REGIONS orofacand SPACES Regio colli anterior anterior neck triangle Trigonae : submentale, submandibulare, caroticum (musculare), regio suprasternalis Triangles : submental, submandibular, carotic (muscular), orofacsuprasternal region podkožní sval na povrchové krční fascii r. colli nervi facialis ovládá napětí kůže krku Platysma orofac proc. mastoideus manubrium sterni, clavicula Sternocleidomastoid m. n.accessorius (XI) + branches sternocleidomastoideus from plexus cervicalis orofac Punctum nervosum (Erb ´s point) : there C5 and C6 nerves are connected, + branches from suprascapulari and subclavian nerves orofacWilhelm Heinrich Erb (1840 - 1921), German neurologist orofac orofac mm. suprahyoid suprahyoidei and et mm. infrahyoid orofacinfrahyoidei muscles orofac Thyroid gland and vascular + nerve bundle in neck orofac orofac Žíly veins orofac štítná žláza příštitné orofactělísko a. thyroidea inferior n. laryngeus inferior