Ethiopia Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Aman Andom

Remembering unique Eritreans in contemporary history A short biographical sketch Of General Aman Andom Source: google.com Compiled and edited from cyber sources By Emnetu Tesfay Stavanger, Norway September, 20 14 List of content Early life and personal data Exceptional hero of war and peace A strong leader equipped with knowledge, principle and justice A person of amazing character combinations: Victorious as a soldier Principled as a person Guided by respect of law and humanity General Aman as a family man and a churchgoer Popular across borders and a pride to nations Prominence in Andom family. Siblings prominent in their own right. End of life: Tragic but exit with pride Early life and personal data Name meaning & history The name Aman has its own meaning in Geez but many use it as a shortened version of the masculine-gender name Ammanuel. In Hebrew, as in biblical name, the meaning of the name Ammanuel is: "God is with us". This was the foretold name of the Messiah in the Old Testament. It has been used by the Christian population in Eritrea and Ethiopia though it has not been widespread. Pastor Mussa Aron in his book ‘dictionary of Eritrean names’ describes the name Aman as meaning ‘the Truth’. It gives confirmation of reality to events, situations and deeds. The name is also widely used in the Islamic world with the meaning: Protection. Fearless. Interestingly enough when I googled I found out what Soul Urge describes personalities with that name. ‘People with this name tend to be creative and excellent at expressing themselves. -

PM Abiy Ahmed Wins Nobel Peace Prize

The Monthly Publication from the Ethiopian Embassy in London Ethiopian News October 2019 Inside this issue Technical Talks on GERD must and will succeed……………………………………..………………………………..2 CONNECT WITH US Ambassador Fesseha presents his credentials to Her Majesty the Queen………………………………....4 THEY DID IT! UK and Ethiopian amputee duo ascend Ethiopia’s highest mountain…………………..7 Habeshaview - bringing Ethiopian film to London theatres………………………………………………………9 Prime Minister Abiy’s Book on MEDEMER launched……………………………………………………………….16 President Sahle -Work delivers maiden address at the opening of Parliament ………………………..17 Ethiopia successfully hosts the Social Enterprise World Forum……………………………………………..18 “You are looking at a new Ethiopia...we hope you jump in and ride with us” – Dr Eyob…………….20 Ethiopia at World Travel Market London……………………………………………………………………………….22 More than 200,000 visitors arrive in Ethiopia on e -Visa…………… ……………………………………………24 Kenenisa wins Berlin Marathon 2 seconds short of the world record……………………………………..26 @EthioEmbassyUK Ethiopia: We’re open for business says mining minister …………… …………………………………………..28 PM Abiy Ahmed wins Nobel Peace Prize Ethiopian News File Photo: Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed with Egypt's President Egypt's President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi Technical Talks on GERD must and will succeed On 11th October 2019, the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize embodied by Ethiopia’s role in the establishment of was awarded to Ethiopian Prime Minister, Dr Abiy the first and only all-inclusive basin-wide Ahmed. A first for the nation, the awarding of the institution in the history of the River – the Nile Basin 100th edition of the Prize is deserved recognition of Initiative – and in its ratification of the Cooperative Ethiopia’s indefatigable commitment to the Framework Agreement (CFA). -

Ethiopia, the TPLF and Roots of the 2001 Political Tremor Paulos Milkias Marianopolis College/Concordia University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarWorks at WMU Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU International Conference on African Development Center for African Development Policy Research Archives 8-2001 Ethiopia, The TPLF and Roots of the 2001 Political Tremor Paulos Milkias Marianopolis College/Concordia University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.wmich.edu/africancenter_icad_archive Part of the African Studies Commons, and the Economics Commons WMU ScholarWorks Citation Milkias, Paulos, "Ethiopia, The TPLF nda Roots of the 2001 Political Tremor" (2001). International Conference on African Development Archives. Paper 4. http://scholarworks.wmich.edu/africancenter_icad_archive/4 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for African Development Policy Research at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Conference on African Development Archives by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ETHIOPIA, TPLF AND ROOTS OF THE 2001 * POLITICAL TREMOR ** Paulos Milkias Ph.D. ©2001 Marianopolis College/Concordia University he TPLF has its roots in Marxist oriented Tigray University Students' movement organized at Haile Selassie University in 1974 under the name “Mahber Gesgesti Behere Tigray,” [generally T known by its acronym – MAGEBT, which stands for ‘Progressive Tigray Peoples' Movement’.] 1 The founders claim that even though the movement was tactically designed to be nationalistic it was, strategically, pan-Ethiopian. 2 The primary structural document the movement produced in the late 70’s, however, shows it to be Tigrayan nationalist and not Ethiopian oriented in its content. -

Nationalism As a Contingent Event: Som Ereflections on the Ethio-Eriterean Experience

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU International Conference on African Center for African Development Policy Development Archives Research 8-2001 Nationalism as a Contingent Event: Som eReflections on the Ethio-Eriterean Experience Mesfin Araya City University of New York (CUNY) Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/africancenter_icad_archive Part of the African Studies Commons, and the Economics Commons WMU ScholarWorks Citation Araya, Mesfin, "Nationalism as a Contingent vE ent: Som eReflections on the Ethio-Eriterean Experience" (2001). International Conference on African Development Archives. 8. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/africancenter_icad_archive/8 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for African Development Policy Research at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Conference on African Development Archives by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact wmu- [email protected]. NATIONALISM AS A CONTINGENT EVENT: SOME REFLECTIONS ON ETHIO-ERITREAN EXPERIENCE* Mesfin Araya * This paper is a bare outline of a larger manuscript near completion. Dr. Mesfin Araya is a professor of African and African-American Studies and Director of its Research Center at York College, CUNY. Background What is politically significant and what really attracts scholarly research in any nationalism is the awakening of the masses - i.e. the effective transition from elite-based to mass- based nationalism; this study is concerned with that transition in the Eritrean experience in the modern political history of Ethiopia. Eritrea is a multi-ethnic society comprising eight linguistic groups, but historically, the great cultural and political divide has been religion - with roughly equal population distribution between Christians and Moslems. -

Democracy Deficiency and Conflict in the Horn of Africa Making Sense of Ethiopia’S December 2006 War in Somalia

Democracy Deficiency and Conflict in the Horn of Africa Making Sense of Ethiopia’s December 2006 War in Somalia Solomon Gashaw Tadese Master’s Program in Peace and Conflict Studies (PECOS) Department of Political Science UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2012 ii Democracy Deficiency and Conflict in the Horn of Africa Making Sense of Ethiopia’s December 2006 War in Somalia Solomon Gashaw Tadese A Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Peace and Conflict Studies Master’s Program in Peace and Conflict Studies (PECOS) Department of Political Science UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2012 iii © Solomon Gashaw Tadese 2012 Democracy Deficiency and Conflict in the Horn of Africa: Making Sense of Ethiopia’s December 2006 War in Somalia http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo iv Abstract Ethiopia, situated at the heart of the volatile Horn of Africa, has long found itself in various conflicts that have ravaged the region. Among them is its 2006 war with the Union of Islamic Courts (UIC) inside Somalia in support of the country’s weak Transitional Federal Government (TFG). It was a major projection of power by an African state in another country that ended up with Ethiopia’s ‘occupation’ of Somalia for the next two years. Nonetheless, the nature of the threat, the scale of the military operation, the justifications given to it and the context in which it was conducted show that it would have been unlikely to fight the war had Ethiopia been a democracy. Despite the conduct of periodic elections since the current EPRDF regime militarily took power in 1991, its rule has been characterized as authoritarian. -

F a S T Update Ethiopia Special Update July to December 2006

F A S T Update Ethiopia Special Update July to December 2006 T S A F © swisspeace FAST Update Ethiopia | July to December 2006 | Page 2 Contents Country Stability and Conflictive Domestic Events 3 Conflictive and Cooperative International Events 11 Outlook 16 Appendix: Map of Ethiopia 17 Acronyms 18 The FAST International Early Warning Program 19 FAST Update Subscription: www.swisspeace.org/fast/subscription_form.asp Monitoring activities in Ethiopia have temporarily been suspended since January 2006 due to the increased curbing of press freedoms and resulting effects on our Local Information Network. Consequently, there is no data set for the period under review. We have, however, included in this Special Update, a detailed list of events that are pertinent to the themes covered as background to the qualitative analysis. Contact FAST International: Country Expert: Phone: +41 31 330 12 19 Anonymous Fax: +41 31 330 12 13 mailto:[email protected] www.swisspeace.org/fast © swisspeace FAST Update Ethiopia | July to December 2006 | Page 3 Country Stability and Conflictive Domestic Events • Compared with the first half of the year, in the second half of 2006 internal conflictive events registered a sharp decline. The expected possibility that, given the high degree of disaffection particularly among the urban youth driving growing numbers into militancy and the massive Eritrean support for the violent opposition, bomb attacks and armed infiltration into the peripheral areas might increase, did not materialize. On the one hand this was a result of the past and on-going governmental counter-measures to curb such activities. On the other hand, however, this was due to the internal problems of both the legal opposition within the country and the externally based one. -

Ethiopian Embassy UK Newsletter October 2018 Issue

The Monthly Publication from the Ethiopian Embassy in London Ethiopian October 2018 News Inside this issue PM Abiy’s memorable visit to Europe………………………………………… ……………………………………………6 CONNECT WITH US Quadruple amputee to scale Ethiopia’s highest mountain………… …………………………………………….7 Addis Fine Art showcases Ethiopian art at 1-54 Contemporary Art Fair in London…………………9 UK and Ethiopia sign £176 million grant……………………………………………………………………………….10 UK-Ethiopia Trade and Investment Forum affirms Ethiopia is open for Business………………….12 Ethiopia makes ‘strong gains’ from FDI flow…………………………………………………………………………14 Clothing giant Calzedonia opens its first African factory in Ethiopia………………………………………15 Ethiopian Diaspora Trust Fund goes live…………………………………… …………………………………………16 th 47,500 participants registered for the Great Ethiopian Run – 18 November………………………17 Ethiopia launches visa-on-arrival for African travellers…………… ………………………………………….18 @EthioEmbassyUK Meet the 19 -year-old tech genius coding at Ethiopia's first AI lab …………………………………………19 Ethiopia Shows the World that Women can Lead Country now boasts first female President, Supreme Court President and gender-balanced Cabinet Page 2 Ethiopian News Ethiopia’s three weeks of historic firsts Women take centre stage in Prime Minister Abiy’s new Government line up In just three weeks, Ethiopia made Aisha Mohammed, formerly Minister history with the elevation of women to of Construction, will now serve as top government posts: a cabinet Defence Minister – the first woman to reshuffle saw a gender-balanced hold that position in the country. cabinet with women taking up half the ministerial posts, the first female Muferiat Kamil will lead the newly- president and first female supreme established Ministry of Peace, which court president. will oversee the intelligence and security agencies. -

Leaders' Dialogue on Africa COVID-Climate Emergency

LEADERS’ DIALOGUE ON THE AFRICA COVID-CLIMATE EMERGENCY Agenda Tuesday, 6 April, 2021 – 1 – 3 p.m. (GMT) CONTEXT The Covid-19 pandemic and climate change have combined to create compound crises for the world. For Africa, besides fighting the pandemic, this also amplifies the need to rapidly adapt to climate change. Although Africa did relatively well to shield itself from the worst of the health crisis in 2020, the impact of the pandemic on Africa’s development is already clear: the first recession in 25 years, with economic activity expected to have dropped by more than 3% in 2020, and as many as 40 million people falling into extreme poverty. African countries will need a comprehensive support package that drives growth and investments, and reaps the full benefits of healthy and decent jobs to re-start their economies and embark on a low carbon, resilient and inclusive recovery. Improved access to finance, at scale, will be key to simultaneously address urgent development needs including renewable energy access for all and to implement climate action plans. To keep the 1.5°C temperature goal of the Paris Agreement within reach all countries, including the G20 and other major emitters, will need to do their part by setting and translating net zero by mid-century commitments as stipulated in the Paris AGreement into ambitious and credible 2030 tarGets. This will be critical to limit the most extreme impacts of climate change on the African continent and its people. The African Development Bank and the Global Center on Adaptation (GCA) have responded to the urgent call by African leaders for a new and expanded effort to shore up momentum on Africa’s climate adaptation efforts. -

Ethiopia Assessment

ETHIOPIA COUNTRY ASSESSMENT OCTOBER 2002 Country Information and Policy Unit IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE Home Office, United Kingdom Ethiopia October 2002 CONTENTS 1 SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 – 1.4 2 GEOGRAPHY 2.1 – 2.3 3 Economy 3.1 4 HISTORY 4.1 – 4.55 Early Ethiopia to the End of the Monarchy 4.1 The Dergue and the "Red Terror" 4.2 – 4.33 Ethnic Resistance 1974 to 1991 and the Overthrow of Mengistu 4.4 – 4.11 The Transition, Eritrea and Federalism 4.12 – 4.14 The Elections of 1992 and 1994 4.15 – 4.20 1995 CPR & National State Elections, Dergue Trials 4.21 – 4.27 Border Conflict With Eritrea 1998-2001 4.28 – 4.38 National Elections May 2000 4.39 – 4.44 Events of 2001 and 2002 4.45 – 4.55 5 STATE STRUCTURES 5.1 – 5.65 The Constitution 5.1 – 5.5 - Citizenship and Nationality 5.6 Political System 5.7 – 5.27 - Political Overview 5.7 - The Executive Branch 5.8 – 5.9 - The Legislative Branch 5.10 - Ethiopian Politics in General 5.11 – 5.12 - Ethnicity in Ethiopian Politics 5.13 – 5.14 - The Ethiopian Peoples Revolutionary Democratic Party 5.15 – 5.17 - The Opposition 5.18 – 5.25 - Former Members of the Dergue/Workers Party of Ethiopia 5.26 – 5.27 The Judiciary 5.28 – 5.36 - Overview 5.28 – 5.33 - Recent Experience 5.34 – 5.35 Legal Rights/Detention 5.36 – 5.40 - Overview 5.36 – 5.38 - Recent Experience 5.39 – 5.40 Internal Security 5.41 – 5.42 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.43 – 5.47 - Overview 5.43 – 5.46 - Recent Experience 5.47 The Military 5.48 – 5.50 - Military Service 5.48 - Child Soldiers 5.49 – 5.50 Medical Services 5.51 -

General Aman Andom

Remembering unique Eritreans in contemporary history A short biographical sketch Of General Aman Andom Source: google.com Compiled and edited from cyber sources By Emnetu Tesfay Stavanger, Norway September, 20 14 List of content Early life and personal data Exceptional hero of war and peace A strong leader equipped with knowledge, principle and justice A person of amazing character combinations: Victorious as a soldier Principled as a person Guided by respect of law and humanity General Aman as a family man and a churchgoer Popular across borders and a pride to nations Prominence in Andom family. Siblings prominent in their own right. End of life: Tragic but exit with pride Early life and personal data Name meaning & history The name Aman has its own meaning in Geez but many use it as a shortened version of the masculine-gender name Ammanuel. In Hebrew, as in biblical name, the meaning of the name Ammanuel is: "God is with us". This was the foretold name of the Messiah in the Old Testament. It has been used by the Christian population in Eritrea and Ethiopia though it has not been widespread. Pastor Mussa Aron in his book ‘dictionary of Eritrean names’ describes the name Aman as meaning ‘the Truth’. It gives confirmation of reality to events, situations and deeds. The name is also widely used in the Islamic world with the meaning: Protection. Fearless. Interestingly enough when I googled I found out what Soul Urge describes personalities with that name. ‘People with this name tend to be creative and excellent at expressing themselves. -

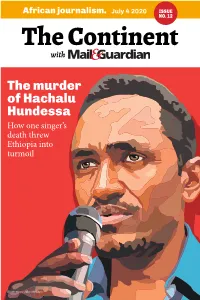

The Continent ISSUE 12

African journalism. July 4 2020 ISSUE NO. 12 The Continent with The murder of Hachalu Hundessa How one singer’s death threw Ethiopia into turmoil Illustration: John McCann Graphic: JOHN McCANN The Continent Page 2 ISSUE 12. July 4 2020 Editorial Abiy Ahmed’s greatest test When Abiy Ahmed became prime accompanying economic crisis, from minister of Ethiopia in 2018, he made which Ethiopia is not spared. the job look easy. Within months, he had released thousands of political All this occurs against prisoners; unbanned independent media and opposition groups; fired officials the backdrop of the implicated in human rights abuses; and global pandemic and made peace with neighbouring Eritrea. the accompanying Last year, he was rewarded with the economic crisis Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of his efforts in brokering that peace. But the job of prime minister is never The future of 109-million Ethiopians easy, and now Abiy faces two of his now depends on what Abiy and his sternest tests – simultaneously. administration do next. The internet With the rainy season approaching, and information blackout imposed this Ethiopia is about to start filling the week, along with multiple reports of Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam brutality from state security forces and on the Blue Nile. No deal has been the arrests of key opposition leaders, are concluded with Egypt and Sudan, who a worrying sign that the government are both totally reliant on the waters of is resorting to repression to maintain the Nile River, and regional tensions are control. rising fast. Prime Minister Abiy was more than And then, this week, the assassination happy to accept the Nobel Peace Prize of Hachalu Hundessa (p15), an iconic last year, even though that peace deal singer and activist, sparked a wave of with Eritrea had yet to be tested (its key intercommunal conflict and violent provisions remain unfulfilled by either protests that threatens to upend side). -

Downloaded from the Internet

FSS MONOGRAPH SERIES 3 DEMOCRATIC ASSISTANCE TO POST-CONFLICT ETHIOPIA Impact and Limitations Dessalegn Rahmato Forum for Social Studies and Meheret Ayenew Faculty of Business and Economics Addis Ababa University Forum for Social Studies Addis Ababa The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of FSS or its Board of Advisors. Financial support for the printing of this publication was provided by the ROYAL NORWEGIAN EMBASSY for which we are grateful. Copyright: © The Authors and Forum for Social Studies 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements i Acronyms ii Abstract v Preface viii I Country Introduction 1 1 Background 1 2 Conflict History 4 3 The Elusive Peace 7 4 Post Conflict Assistance 10 a Development Assistance 12 b Humanitarian/Relief Assistance 16 c Assistance to Democratization and Governance 18 5 Methodology 20 6 Outline of Study 22 II International Electoral Assistance 24 1 Introduction 24 2 Electoral Context 25 3 Post-Conflict Elections 27 a The 1992 Interim Elections 27 b The 1995 Constituent Assembly Elections 29 c The 1995 First National Assembly Elections 30 d The 2000 National Elections 31 4 International Electoral Assistance 36 a Technical and Financial Assistance for Constitutional and Legal Reforms 36 b Assistance to the National Electoral Board 38 c Political Party Assistance 42 d International Election Monitoring 44 e Civic and Voter Education 44 5 Impact of Electoral Assistance 45 6 Conclusions 47 III International Human Rights Assistance 49 1 Background: History of Human Rights Violations 49 2 Post-Conflict Human Rights Context 51 3 International Assistance to Human Rights 55 a Human Rights Observation 55 b Red Terror Tribunals…………………………………….