Il Capitale Culturale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Best Tours in Rome"

"Best Tours in Rome" Created by: Cityseeker 9 Locations Bookmarked Colosseum "Symbol of Rome" The magnanimous proportions of the Colosseum have long been a source of wonder. Originally envisioned in 70 CE, the construction of this grand structure was completed in 80 CE. At that time, it is believed that this vast amphitheater could seat upwards of 50,000 spectators at once. The Colosseum also features on the Italian version of the five-cent Euro. by TreptowerAlex Deemed as one of the Seven Wonders of the World, the Colosseum was designed to be a horse racing circuit and arena for animal fighting and gladiatorial battles, although it has also hosted significant religious ceremonies in its early days. It is a symmetrical wonder set in the historic landscape of Rome's heart. The enormous ruin is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is considered by many to be an iconic symbol of Italy. +39 06 699841 parcocolosseo.it/area/colosseo/ Piazza del Colosseo 1, Rome Basilica di San Clemente al Laterano "Basilica on Three Levels" A visit to Basilica di San Clemente al Laterano is a fascinating journey through time. From the upper basilica, which dates from the beginning of the 12th Century and whose apse boasts the mosaic The Triumph of the Cross, one passes into the 4th-century lower basilica, and, via a stairway, by Nicholas Hartmann down to the Roman constructions and the mitreo, a 3rd-century temple dedicated to the God Mithra. Of particular interest are the frescoes in the chapel of St Catherine, painted between 1428 and 1431 by Masolino da Panicale, possibly with the collaboration of Masaccio. -

Denominazione Codice Discrizione Scopo Sedeente OPERA

Denominazione Codice DIscrizione Scopo SedeEnte OPERA NAZIONALE PER I FIGLI DEGLI AVIATORI 1 15/01/1940 EDUCAZIONE FIGLI DEGLI AVIATORI (ORFANI) ROMA - VIALE DELL'UNIVERSITA' N°4 FONDAZIONE DI ASSISTENZA E SOLIDARIETA' - ONLUS 1 21/01/1995 ASSISTENZA SOCIALE ROMA - VIA NAZIONALE N°91 FONDAZIONE TERZO PILASTRO - ITALIA E MEDITERRANEO (scissa in: Fondazione terzo pilastro Internazionale iscritta CULTURALE PER PROMUOVERE SOSTENERE E 1 04/01/1996 ROMA - VIA MARCO MINGHETTI N°17 al n.1275/2018 e nella Fondazione Cultura ed Arte iscritta DIFFONDERE L'IDEA DI IMPRESA SOCIALE ECC. al n.1276/2018) CASSA UFFICIALI 1 07/01/1998 SOVVENZIONE PENSIONI INTEGRATIVE ROMA - VIA MARSALA N°104 PARROCCHIA S. ENRICO 1 13/01/1999 RELIGIONE E CULTO ROMA - VIALE RATTO DELLE SABINE N°7 CONGREGAZIONE DELLE PIE DISCEPOLE DEL DIVIN 1 10/01/2000 RELIGIONE E CULTO ROMA - VIA GABRIELE ROSSETTI N°17 MAESTRO FINALITA' EDUCAZIONE ISTRUZIONE FORMAZIONE ROMA - CIRCONVALLAZIONE CLODIA MISSIONE EDUCATIVA CONDIVISA (M.E.C.) 1 19/04/2001 BAMBINI RAGAZZI ADULTI SENZA N°163/171 INT.2 DISCRIMINAZIONI FONDAZIONE EDOARDO AGNELLI 2 15/01/1940 BORSE DI STUDIO A FIGLI DI AVIATORI ROMA - VIALE UNIVERSITA' N. 4 FONDAZIONE "ISTITUTO GUGLIELMO TAGLIACARNE" PER LA PROMOZIONE DELLA CULTURA ECONOMICA PROMUOVERE E DIFFONDERE LA CULTURA 2 23/01/1995 ROMA - VIA NERVA N.1 (trasformata in S.r.l.) (CANCELLATA IN DATA 4 GIUGNO ECONOMICA 2019) FONDO NAZIONALE DI GARANZIA 2 05/01/1996 TUTELA AGENTI DI CAMBIO ROMA - VIA GIACOMO PUCCINI, N°9 PROMUOVERE E FAVORIRE LA RICERCA TECNICO- SCIENTIFICA NEL CAMPO DELL'UROLOGIA LO SOCIETA' ITALIANA DI UROLOGIA 2 16/01/1998 ROMA - VIA GIOVANNI AMENDOLA N°46 SVILUPPO ED IL CORRETTO ESERCIZIO DELLA PROFESSIONE UROLOGICA FONDAZIONE LEONE CAETANI 2 15/01/1999 CONOSCENZA DEL MONDO MUSULMANO ROMA - VIA DELLA LUNGARA N.10 LOGOS INC. -

Catechesi Con Arte Nelle Chiese Di Roma, Roma, Di Chiese Nelle Arte Con Catechesi Di Itinerari Nostri Nei

Programma Divina Rivelazione Divina Missionarie della della Missionarie 2018-2019 a cura delle cura a CATECHESI CON ARTE CON CATECHESI Imparare Roma: la Bellezza tra Cielo e terra. terra. e Cielo tra Bellezza la Roma: Imparare Carissimi amici, MISSIONARIE DELLA DIVINA RIVELAZIONE nei nostri itinerari di Catechesi con Arte nelle chiese di Roma, Via delle Vigne Nuove, 459 - 00139 Roma vogliamo sentirci pellegrini nella vita di ogni giorno; il pellegrino ha la certezza che la morte non è un muro da abbattere, ma la porta che Tel/Fax 06 87130963 si apre sull’Eternità. I luoghi sacri ci ricordano che in Cristo cielo e terra non sono separati, ma che tutti i credenti in Lui formano un solo Per sostenere la nostra missione: corpo e il bene degli uni è comunicato agli altri. “Noi crediamo alla Banca Prossima comunione di tutti i fedeli di Cristo, di coloro che sono pellegrini su IT59K0335901600100000103420 questa terra, dei defunti che compiono la loro purificazione e dei beati del cielo; tutti insieme formano una sola Chiesa; noi crediamo che in questa comunione l’amore misericordioso di Dio e dei suoi santi [email protected] ascolta costantemente le nostre preghiere” [Beato Paolo VI, Credo del www.divinarivelazione.org popolo di Dio, 30]. Dio ci benedica E la Vergine ci protegga Guide ufficiali della Basilica di San Pietro e dei Musei Vaticani per Le Missionarie della Divina Rivelazione itinerari di Arte e Fede IT59K0335901600100000103420 missione: Banca Prossima Prossima Banca missione: Per sostenere la nostra nostra la sostenere -

Medieval Rome and Its Monuments

Dr. Max Grossman Art History 3399/4383 UTEP/John Cabot University Summer II, 2019 Tiber Campus, room ???? CRN# 36302/36303 [email protected] MW 9:00am-1:00pm Cell: (39) 340-4586937 Medieval Rome and its Monuments Art History 3399 is a specialized upper-division course on the urbanism, architecture, sculpture and painting of the city of Rome from the reign of Emperor Constantine to the end of the duecento. Through its artistic treasures, we will trace the transformation of the city from the largest and most populous metropolis on earth to a modest community of less than thirty thousand inhabitants, from the political and administrative capital of the Roman Empire to the spiritual epicenter of medieval Europe. We will focus in particular on the development of the Catholic Church and the papacy; the artistic patronage of popes, cardinals, monasteries, and seignorial families; the cult of relics and the institution of pilgrimage; and the careers of various masters, both local and foreign, who were active in the city. As we examine the style, iconography and symbolic meaning of medieval Roman artworks and place them within their historical, socio-political and theological contexts, we will consider the medieval reception of antiquity, the systematic recycling of Rome’s ancient fabric, and the renovatio urbis that began in Carolingian times and accelerated in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. INSTRUCTOR BIOGRAPHY Dr. Grossman earned his B.A. in Art History and English at the University of California- Berkeley, and his M.A., M.Phil. and Ph.D. in Art History at Columbia University. After seven years of residence in Tuscany, he completed his dissertation on the civic architecture, urbanism and iconography of the Sienese Republic in the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance. -

Favorite Places in Rome Provided by Marie Lorenz, December 2017

Favorite Places in Rome provided by Marie Lorenz, December 2017 Marie lived in Rome during her third year at the Rhode Island School of Design. She returned for a second year as a Fellow at the American Academy in Rome. http://www.aarome.org/ She mapped out each of the spots listed below here. 1) THE TRASTEVERE CHURCHES These churches are only a 15 minute walk from Campo de Fiori and a bit off the tourist path, so they present a rare opportunity to sit quietly with some of the most beautiful artwork in Rome, for free! San Francesco a Ripa Piazza di S. Francesco d'Assisi, 88, 00153 Roma This early Franciscan convent holds Bernini’s masterpiece, Beata Ludovica Albertoni. "The sculpture and surrounding chapel honors a Roman noble woman who entered the Order of St. Francis following the death of her husband. The day before her own death from fever, Ludovica received the eucharist and then ordered everyone out of her room. When her servants were finally recalled, “they found her face aflame, but so cheerful that she seemed to have returned from Paradise.” (paraphrased from wikipedia) By representing this decisive moment, and like many of his other sculptures, Bernini seems to mingle the idea of physical ecstasy and religious martyrdom. In its day, this sculpture would have scandalized the recently reformed protestant church which considered any representation of a divine figure blasphemous. Bernini finished the sculpture in 1674 when he was seventy one years old. Santa Cecilia in Trastevere Piazza di Santa Cecilia, 22, 00153 Roma 5th-century church devoted to the Roman martyr Saint Cecilia. -

Santa Maria in Cosmedin

La basilica di Santa Maria in Cosmedin è un luogo di culto cattolico di Roma, situato in piazza della Bocca della Verità, nel rione Ripa; officiata dalla Chiesa cattolica greco-melchita, ha la dignità di basilica minore e su di essa insiste l'omonima diaconia. La basilica, frutto dell'ampliamento sotto papa Adriano I (772-790) di un precedente luogo di culto cristiano attestato fin dal VI secolo, fu oggetto di un importante rifacimento nel 1123 ed è attualmente uno dei rari esempi di architet- tura sacra del XII secolo a Roma; è nota per la presenza nel nartece della Bocca della Verità. Un po’di storia Il sito su cui sorge la basilica di Santa Maria in Cosmedin, in epoca romana si trovava al margine sud-orientale del Foro Boario, prossimo al fium Tevere e a Circo Massimo. In quest'area trovava luogo l'Ara massima di Ercole invitto, edificata secondo la tradizione da Evandro dopo che Ercole ebbe ucciso il gigante Caco, e che assunse la sua conformazione definitiva con una ricostruzione nel II secolo a.C. Alla metà del IV secolo d.C. venne edificata immediatamente ad ovest dell'Ara massima e ad essa adiacente un'aula porticata, posta su un podio e delimitata da arcate poggianti su colonne; essa era molto probabilmente priva di copertura in quanto sarebbe risultata molto costosa a causa della notevole altezza delle pareti (18 metri), nonché soggetta agli incendi che avrebbe potuto appiccare il fuoco dei sacrifici del santuario attiguo; secondo altri studi, invece, la presenza di stucchi al suo interno avrebbe necessariamente richiesto la presenza di un tetto. -

Arte a Servizio Dell'incontro Con Gesù Cristo

PRESENTAZIONE Lo scopo della presente pubblicazione, non riguarda principalmente la conoscenza del mosaico, della sua tecnica e dei capolavori a cui essa ha dato vita, ma è quello di guidare il lettore a confrontarsi con alcune opere per ascoltarne la voce, apprezzarne la bellezza e accogliere il messaggio di cui esse sono tramite. Non si riflette mai abbastanza sul fatto che, a fondamento di ciò che noi siamo – personalità, formazione, sensibilità, cultura – si trova l’esperienza, vale a dire l’incontro con qualcuno o con qualcosa che investe la sfera del nostro essere e la modifica profondamente. L’arte entra decisamente nell’esperienza personale di ciascuno e contribuisce a darle forma e ad orientarla. Pur senza fare riferimenti all’indagine filosofica, non si può non essere d’accordo con l’affermazione secondo cui l’arte è «una forma di arricchimento, intensificazione e ampliamento dell'esperienza comune»1. Essa crea un’esperienza di senso che restituisce significati, orienta alla verità, induce al pensiero del buono. Tutto ciò è ancora più vero in relazione alla cosiddetta arte cristiana, ma sarebbe meglio dire dell’arte a servizio dell’incontro con Gesù Cristo. Alla base dell’esperienza cristiana, infatti, si trova la dinamica del vedere. Bastino due citazioni, entrambe tratte dagli scritti dell’apostolo Giovanni. Nel Prologo del suo Vangelo, Giovanni afferma: «Il Verbo si fece carne e venne ad abitare in mezzo a noi; e noi vedemmo la sua gloria» (Gv 1,14); parimenti nella sua Prima Lettera, proclama che «la vita si è fatta visibile, noi l’abbiamo veduta e di ciò rendiamo testimonianza» (1 Gv 1,1-2). -

Medieval Rome and Its Monuments

Dr. Max Grossman Art History 5390 UTEP/John Cabot University Summer II, 2014 Tiber Campus, room 1.3 CRN# 34255 [email protected] MW 9:00am-1:00pm Medieval Rome and its Monuments Dr. Grossman earned his B.A. in Art History and English at the University of California- Berkeley, and his M.A., M.Phil. and Ph.D. in Art History at Columbia University. After seven years of residence in Tuscany, he completed his dissertation on the civic architecture, urbanism and iconography of the Sienese Republic in the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance. He served on the faculty of the School of Art and Design at San Jose State University in 2006-2009, taught art history for Stanford University in 2007-2009, and joined the Department of Art at the University of Texas at El Paso as Assistant Professor of Art History in 2009. During summers he is Coordinator of the UTEP Department of Art in Rome program and Adjunct Assistant Professor of Art History at John Cabot University. He has presented papers and chaired sessions at conferences throughout the United States, including at the annual meeting of the Renaissance Society of America, and in Europe, at the annual meetings of the European Architectural History Network. In April 2012 in Detroit he chaired a session at the 65th Annual Meeting of the Society of Architectural Historians: “Medieval Structures in Early Modern Palaces;” and in the following June he chaired a session at the 2nd International Meeting of the European Architectural History Network in Brussels: “Architecture and Territoriality in Medieval Europe,” which was published in the conference proceedings. -

Download the Complete List

Guided tours and educational visits Last update: 2021-09-22 23:40 1. Archeologia in Comune - Il trionfo dell’acqua: il 8. Caravaggio: tra arte e vita privata - Ass. ninfeo di Alessandro Severo all’Esquilino Bellaroma.info Date: 2021-09-22 Date: 2021-09-25 Venue: Trofei di Mario Venues: Chiesa San Luigi dei Francesi, Chiesa Sant'Agostino in Address: Piazza Vittorio Emanuele II Campo Marzio, Chiesa Santa Maria del Popolo Web site: Address: Piazza di San Luigi de' Francesi www.sovraintendenzaroma.it/content/archeologia-comune-il-trionfo Mobile phone: 3407874301 -dell’acqua-il-ninfeo-di-alessandro-severo-all’esquilino-1 Web site: www.bellaroma.info 2. Mausoleo di Augusto - Ass. Ars in urbe 9. Ci vediamo sulla via Biberatica. Giornate Europee Date: 2021-09-22 del Patrimonio 2021 Venue: Mausoleo di Augusto Date: 2021-09-25 Address: Piazza Augusto Imperatore, 31 Venue: Mercati di Traiano - Museo dei Fori Imperiali Mobile phone: 3299740531 Address: Via Quattro Novembre, 94 Web site: www.arsinurbe.org Telephone: 060608 dalle 9.00 alle 19.00 Web site: www.mercatiditraiano.it/didattica/ci-vediamo-sulla-biberatica 3. aMICi online - Il Grande Emiciclo dei Mercati di Traiano e le Aule di testata. Soluzioni costruttive e impianto decorativo 10. C’erano una volta una lupa e due gemelli . Date: 2021-09-23 Giornate Europee del Patrimonio 2021 Venue: Mercati di Traiano - Museo dei Fori Imperiali Date: 2021-09-25 Address: Via Quattro Novembre, 94 Venue: Musei Capitolini Telephone: 060608 dalle 9.00 alle 19.00 Address: Piazza del Campidoglio, 1 - Via delle Tre Pile, 1 Web site: Telephone: 060608 - bookshop 06 82077434 www.mercatiditraiano.it/didattica/amici-online-il-grande-emiciclo-dei-mer Web site: cati-di-traiano-e-le-aule-di-testata www.museicapitolini.org/didattica/c-erano-una-volta-una-lupa-e-due-ge melli 4. -

San Clemente Al Laterano Excavations

San Clemente al Laterano Excavations The site of the basilica has a history that goes back to the Republican era of Ancient Rome. The building underwent multiple transformations, the latest of which took place in the early 12th century. After excavations were done by Irish Dominicans, these changes can be seen through the layers of construction underneath the present-day building. Each layer stems from a different time period and shows how Christianity had a growing influence on Roman life and culture. [2] The entrance to the excavations is through the shop, where you also pay the fee. They are extensive, interesting and well described in the many signs down there, so it's worth the money. Especially, signs by the frescoes provide explanations for them -although buying a guidebook is still a good idea. [1] The access staircase to the right of where you pay, which displays many fragments of sculpture, emerges at the right hand end of the narthex or entrance porch of the old church. From there, you can enter three zones separated by walls formed by blocking up the original arcades. These divide the area into the central nave (which is unequally divided by a third foundational wall), the right hand aisle and the left hand aisle. At the end of the latter is the staircase down to the next level, the ancient Roman remains. Needless to say, the vaults and the brick piers are modern. 4th century church The church was built into and above a large Roman building, and oversailed a narrow alleyway and the remains of the house-church of Flavius Clemens. -

Stemma Di Roma

Stemma di Roma «Questa signoria [dei Consoli] portò col vessillo dell'aquila S.P.Q.R. le quali lettere così dicono: Senatus PopulusQue Romanus cioè il Senato et Popolo Romano; et queste lettere erano d'oro in campo rosso. L'oro è giallo et appropriato al Sole che dà lume, prudentia et signoria a ciascuno che col suo valore cerca aggrandire. Il rosso è dato da Marte il quale essendo il dio della battaglia, a chi francamente lo segue porge vittoria et maggioranza» (Bernardino Corio, Le Vite degl'Imperatori Incominciando da Giulio Cesare fino à Federico Barbarossa, …) Blasonatura Lo stemma è stato approvato con decreto del 26 agosto 1927. La blasonatura ufficiale è la seguente: «Scudo di forma appuntato di rosso alla croce bizantina posta in capo a destra, seguita dalle lettere maiuscole S.P.Q.R. poste in banda e scalinate, il tutto d'oro.» La Bandiera LAZIO Regione Lazio mod. 1995 in uso Bandiera approntata nel 1995 e mai resa ufficiale, copia fedele del gonfalone adottato insieme allo stemma con legge regionale del 17 settembre 1984 (emendata l'8 gennaio 1986). Il modello originario aveva, come il gonfalone, un bordo blu scuro e la scritta "Regione Lazio" su due righe. La bandiera effettivamente in uso non ha il bordo e la scritta è su una sola linea. L'emblema, di forma ottagonale, reca i colori nazionali e gli stemmi delle cinque province laziali: al centro Roma, in alto Frosinone e Latina, in basso Rieti e Viterbo. Ai lati dell'ottagono, spighe di grano e un ramo di quercia, in alto una corona molto peculiare ROMA Bandiera di Roma, rosso porpora e giallo ocra, colori di antica origine bizantina, con o senza stemma. -

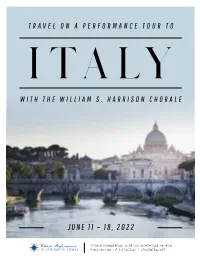

June 11 – 18, 2022

TRAVEL ON A PERFORMANCE TOUR TO I TALY WITH THE WILLIAM S. HARRISON CHORALE JUNE 11 – 18, 2022 41780 W Six Mile Road, Suite 1oo, Northville, MI 48168 P: 866.468.1420 | F: 313.565.3621 | ctscentral.net Price per person after November 30, 2021 READY TO SEE THE WORLD? $4,364 (double occupancy) LEARN MORE & BOOK ONLINE: -$100 Book by November 30, 2021 WWW.CTSCENTRAL.NET/WILLIAMHARRISONCHORALE- Cash discount for payment by cash or check HARRISON-ITALY-202206 -$115 Early booking & cash discount price QUESTIONS? VISIT CTSCENTRAL.NET TO BROWSE OUR FAQ’S OR CALL 866.466.2202 TO SPEAK TO A RESERVATIONS SPECIALIST. $4,149 (double occupancy) DAY 1: SATURDAY, JUNE 11 • OVERNIGHT FLIGHT TO ITALY Depart the USA on overnight flights to Rome. DAY 2: SUNDAY, JUNE 12 • ARRIVE ROME Arrive Rome and meet your professional tour director, transfer by private motor coach to your hotel for lunch and afternoon on your own.. Celebrate Mass this evening, followed by a group welcome dinner. Overnight in Rome. DAY 3: MONDAY, JUNE 13 • ANCIENT ROME TOUR Celebrate Mass at St. Mary Major and attend a performance by William Harrison. Then, the group will enjoy a tour of Ancient Rome, the Coliseum (inside visit), Capitol Hill, the Vittorio Emmanuel Monument (wedding cake), the Roman Forum, Circus Maximus and Michelangelo’s statue of Moses at St. Peter in Chains Church. Free time this evening to explore on your own. Overnight in Rome. DAY 4: TUESDAY, JUNE 14 • ST. SEBASTIAN CATACOMBS | VATICAN MUSEUMS AND SISTINE CHAPEL Celebrate Mass this morning at St.