Locality Pay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Twig of the Branch Branch 1477 West Coast Florida Letter Carriers

The Twig of the Branch Branch 1477 West Coast Florida Letter Carriers Serving: St. Petersburg — Largo — Dunedin — Pinellas Park — Indian Rocks Beach Punta Gorda — Englewood— Bradenton Beach — Palmetto — Ellenton VOLUME 604 VOICE OF BRANCH 1477 March, 2020 Inside This Issue: PRESIDENT’S REPORT By President Joe Henschen President’s Report 1-2 by Joe Henschen Twitter @ JaHe1 St. Pete Grand Prix 2 MDA Annual Golf Outing 3 This month is dedicated to the members of Branch 36 who on March 17, Entry Form 1970, voted to walk off the job, then backed it up. Executive Vice President 4-5 article—Hubble’s Troubles On Saturday March 21, 2020 at the Manhattan Center, 311 W. 34th Street by Chris Hubble New York NY 1000 where the vote took place the NALC will Vice President 5 commemorate the Wildcat Strike of 1970 and honor the heroes who went by Zulma Betancourt out on strike. Editor’s Corner 5-7 th by Judy Dorris Celebrating the 50 anniversary of the walkout in New York City Last Punch Retiree 7 It can be difficult for letter carriers to understand what it was like for our Minutes of the Branch 7-9 brethren to have launched, at 12:01 a.m. on March 18, 1970, what is now by Recording/Financial Secretary called the Great Postal Strike. Today, we are guaranteed a decent wage Ken Grasso and benefits, are protected from management abuses, and are Sergeant at Arms 9 represented by a strong union. But it wasn’t always like that. by Clay Hansen Auxiliary 181 News 9 Letter carriers in the late 1960s were poorly paid and denied collective by Dottie Tutt-Hutchinson bargaining rights. -

Man Sentenced for Assaulting Pregnant Mail Carrier

United States Attorney David E. Nahmias Northern District of Georgia FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Patrick Crosby 1/21/09 (404)581-6016 http://www.usdoj.gov/usao/gan/ FAX (404)581-6160 MAN SENTENCED FOR ASSAULTING PREGNANT MAIL CARRIER Robber Violently Stole Parcel Containing Marijuana Atlanta, GA - HAJJA KENYATTA MARTIN, 35, of Lithonia, Georgia, was sentenced today by United States District Judge William S. Duffey, Jr. to serve 2 years in federal prison on a charge of assaulting and robbing a United States Postal Service mail carrier. United States Attorney David E. Nahmias said, “Like all government employees, mail carriers for the U.S. Postal Service deserve protection while carrying out their official duties. In this robber’s desperate efforts to steal a package containing illegal drugs, he physically restrained and assaulted not just a postal employee, but an expectant mother. Thankfully, both mother and baby are fine. This defendant, however, will pay for his crime by sitting in federal prison for two years.” “The safety of its employees is critical to the manner in which the Postal Service performs its functions. As the law enforcement, security and crime prevention officers of the Postal Service, U.S. Postal Inspectors promptly investigate incidents of assaults and threats against our employees, and we will continue to make these cases high priority. We have no tolerance for acts of violence committed against our employees and criminal charges are initiated whenever possible in federal or state courts,” said Martin D. Phanco, Inspector in Charge, Atlanta Division, U.S. Postal Inspection Service. MARTIN was sentenced to 2 years in prison to be followed by 3 years of supervised release. -

Extensions of Remarks

April 26, 1990 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 8535 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS BENEFITS OF AUTOMATION First-class mail delivery performance was "The mail is not coming in here so we ELUDE POSTAL SERVICE at a five-year low last year, and complaints have to slow down," to avoid looking idle, about late mail rose last summer by 35 per said C. J. Roux, a postal clerk. "We don't cent, despite a sluggish 1 percent growth in want to work ourselves out of a job." HON. NEWT GINGRICH mall volume. The transfer infuriated some longtime OF GEORGIA Automation was to be the service's hope employees, who had thought that they IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES for a turnaround. But efforts to automate would be protected in desirable jobs because have been plagued by poor management and of their seniority. Thursday, April 26, 1990 planning, costly changes of direction, inter "They shuffled me away like an old piece Mr. GINGRICH. Mr. Speaker, as we look at nal scandal and an inability to achieve the of furniture," said Alvin Coulon, a 27-year the Postal Service's proposals to raise rates paramount goal of moving the mall with veteran of the post office and one of those and cut services, I would encourage my col fewer people. transferred to the midnight shift in New Or With 822 new sorting machines like the leans. "No body knew nothing" about the leagues to read the attached article from the one in New Orleans installed across the Washington Post on the problems of innova change. "Nobody can do nothing about it," country in the last two years, the post of he said. -

Postal Worker Appreciation Month” in Suffolk County

Intro. Res. No. 1668-2020 Laid on Table 9/9/2020 Introduced by Presiding Officer Calarco and Legislators Sunderman, Fleming, Anker, Richberg, Berland RESOLUTION NO. 732 -2020, DESIGNATING OCTOBER AS “POSTAL WORKER APPRECIATION MONTH” IN SUFFOLK COUNTY WHEREAS, the United States Postal Service (“USPS”) traces its roots to 1775 during the Second Continental Congress, when Benjamin Franklin was appointed the first postmaster general; and WHEREAS, the Post Office Department was created in 1792 with the passage of the Postal Service Act and was elevated to a cabinet-level department in 1872, with the Postal Reorganization Act of 1970 transforming the United States Postal Service into an independent agency; and WHEREAS, considered an “essential service” by an act of Congress, “The United States Postal Service shall be operated as a basic and fundamental service provided to the people by the Government of the United States, authorized by the Constitution, created by an Act of Congress, and supported by the people.”; and WHEREAS, today the postal service employs 7.3 million people, is one of the largest employers of military veterans and has a diverse workforce, with almost 40% minority employees; and WHEREAS, the USPS continually strives to support the communities it serves; the day before Mother’s Day the postal service conducts the largest one-day food drive in America, collecting more than 75.7 million pounds of food in all 50 states and each year during the holiday season, the USPS sponsors “Operation Santa” to provide a channel where people -

I!1'C[F&!) POSTAL RATE Commlsston WASHINGTON, DC

BEFORE THE i!1‘C[f&!) POSTAL RATE COMMlSStON ‘(3 Ii WASHINGTON, DC. 20266~661 5 2J, p/j 90, pw:,I fi,\iE c”, OFFICEOF r//C s;hkk,>,,,, POSTAL RATE AND FEE CHANGES,2001 i Docket No. R2001-1 RESPONSE OF UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE WITNESS TAYMAN TO INTERROGATORIES OF THE OFFICE OF THE CONSUMER ADVOCATE (OCA/USPS-T&l-21) The United States Postal Service hereby provides the responses of witness Tayman to the following interrogatories of the Office of the Consumer Advocate: OCA/USPS-T6-l-21, filed on October 3,200l. Each interrogatory is stated verbatim and is followed by the response. Respectfully submitted, UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE By its attorneys: Daniel J. Foucheaux, Jr. Chief Counsel, Ratemaking 475 L’Enfant Plaza West, S.W. Washington, D.C. 20260-l 137 (202) 266-2999; Fax -5402 October 17,200l RESPONSE OF UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE WITNESS TAYMAN TO INTERROGATORIES OF THE OFFICE OF THE CONSUMER ADVOCATE OCA/USPS-16-l. The following refer to the USPS FY 2001 and FY 2002 Operating Plans. (a) Please provide the FY 2001 Operating Plan and the most current USPS FY 2002 Operating Plan by accounting periods for Postal Service operating revenues, appropriations, investment income, expenses and volumes. 04 For each of the thirteen accounting periods presented in part “a” of this interrogatory, please provide the most current USPS Operating Plan with operating revenues broken out by mail class and subclass cost categories. RESPONSE: (a) The FY 2001 Operating Plan by accounting period is attached. The FY 2002 accounting period Operating Plan has not been finalized. -

Association for Postal Commerce

Association for Postal Commerce 1901 N. Fort Myer Dr., Ste 401 * Arlington, VA 22209-1609 * USA * Ph.: +1 703 524 0096 * Fax: +1 703 524 1871 Postal News from February 2011: February 28, 2011 The U.S. Postal Service Office of Inspector General invites you to comment on the this week’s “Pushing the Envelope” blog topic: • Bridging the Digital Divide. What is the Postal Service’s role in the digital age? New Audit Projects: LINK here to visit our audit project pages. This week we opened the following new project(s): (Please share any information you may have that would help with this audit currently in progress by clicking on the link below): A new audit project has been started on the external website. • Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Regulations – 11YG019HR000. We are going to look at Postal Service processes in place to prevent and address Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulations, limit their impact on Postal operations, and prevent future violations. • Western Pennsylvania District PVS Scheduling and Staffing – 11XG026NL000. The purpose of this audit is to determine whether scheduling and staffing of Postal vehicle Service (PVS) operations are efficient, effective, and economical. This audit will focus on a district identified and extracted from our Risk Model, Western Pennsylvania. The audit will use current schedules for the facilities in the district and evaluate staffing levels based on need and benchmarking information. Courier, Express, and Postal Observer: The Office of Management and Budget media office has provided the following response to my question regarding why OMB Director Jacob Lew is not testifying at the Postal Hearing this Wednesday. -

Bob· Chester: Trotskyist Leader & Educator by Ed Harris American Workers Party, Led by A.J

JULY 18, 1975 25 CENTS VOLUME 39/NUMBER 27 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE SIOD discriminatory IBVOIIS! LABOR UPSURGE IN ARGENTINA CABINET RESIGNS AS GOVERNMENT IS ROCKED BY MASSIVE STRIKES. PAGE 5. PINE RIDGE I IS BEHIND FBI INVASION: TWO YEARS OF GOVERNMENT TERROR .. PAGE 16. lEW YORK UNION LEADERS RETREAT ON Militant/Mary Scully FIGHT FOR JOBS. PAGE 3. Workers rally in Lisbon. Is Armed Forces Movement leading struggle for socialism? See page 14. WOMEN UN MEETING SHOWS IMPACT OF FEMINIST STRUGGLE. PAGE 9. liNGS. L.A. COPS COVER UP RIGHT WING CAMPAIGN. PAGE 18. 7II In Brief THIS UNCOMMON CAUSE: The Militant has been reporting front of Japan; and if Japan were directly exposed and WEEK'S how Common Cause chief John Gardner has been going to threatened," Helms said, "her intricate economy bat for the two-party system. The Washington Star recently interwoven so closely with the needs and stability ·of the MILITANT asked him if he didn't think that this was a strange cause Western economies-would collapse." for the so-called People's Lobby to embrace "when many 3 Union leaders retreat voters are expressing no confidence in either the Democratic GAY RIGHTS GAIN: The U.S. Civil Service Commission from jobs fight or Republican parties." The question referred to the has backed off from its policy of excluding homosexuals 4 AFSCME ends Pa. strike Common Cause-promoted public election financing law, f~om government jobs. Newly issued guidelines state that with few gains · which provides tax money to the Democrats and Republi court.decisions and injunctions require "the same standard cans, and excludes smaller parties. -

Congress Should Free the Postal Service, Not Bail It out Romina Boccia, David A

BACKGROUNDER No. 3495 | MAY 8, 2020 GROVER M. HERMANN CENTER FOR THE FEDERAL BUDGET Congress Should Free the Postal Service, Not Bail It Out Romina Boccia, David A. Ditch, James L. Gattuso, and Rachel Greszler he United States Postal Service (USPS) was KEY TAKEAWAYS long a dominant force in American life. In the past, it was essential to enabling communi- The United States Postal Service has long T cation among family and friends across the country. been on the road to financial collapse, and Businesses relied on it to contact suppliers and cus- the coronavirus pandemic has only accel- erated its pace. tomers, making interstate commerce itself possible. Those days are long gone. The USPS no longer holds this position. E-mail, Bailing out the Postal Service will texting, and social networking have largely replaced not save it; aid absent reform merely letter mail. Business-to-business correspondence perpetuates its many challenges in is virtually all electronic. Consumers pay most bills today’s digital world. online and are receiving an increasing portion of their bills electronically. As a result of these changes, the Congress can protect both postal workers use of letter mail has shrunk dramatically. First-Class and taxpayers by freeing the USPS from mail volume has plunged by almost 50 percent since political control to enable sustainable and 2001.1 With the exception of package delivery, every competitive operations. category of mail is shrinking. This paper, in its entirety, can be found at http://report.heritage.org/bg3495 The Heritage Foundation | 214 Massachusetts Avenue, NE | Washington, DC 20002 | (202) 546-4400 | heritage.org Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of The Heritage Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before Congress. -

Owney - the Railway Mail Service Mascot

1935 - 2012 VOLUME 43 NUMBER 2 CHAPTER WEBSITE: WWW.NRHS1.ORG FEBRUARY 2012 OWNEY - THE RAILWAY MAIL SERVICE MASCOT NANCY POPE, HISTORIAN SMITHSONIAN NATIONAL POSTAL MUSEUM On July 27, 2011, one of the National Postal Museum’s most interesting objects was commemorated with a United States postage stamp. During his lifetime a scruffy mutt named Owney was the nation’s most famous canine. From 1888 until his death in 1897 Owney rode with Railway Mail Service clerks and mailbags all across the nation. Owney’s story begins in 1888 with his attachment to the mail clerks and mailbags at the Albany, New York, post office. His owner was likely a postal clerk who let the dog walk him to work. Owney was attracted to the texture or scent of the mailbags and when his master moved away, Owney stayed with his new mail clerk friends. He soon began to follow mailbags. At first, he followed them onto mail wagons and then onto mail trains, beginning an almost decade-long story of travels far and wide. Owney’s journeys took him across the United States, into Canada, and possibly Mexico. On August 19, 1895, as part of a publicity stunt for the town of Tacoma, Washington, Owney left that city on a mail steamer and spent the next few months traveling around the world. He docked back in at New OWNEY AND FRIENDS POSING WITH A U.S. RAILWAY York City harbor in late December, returning by train to Tacoma on December 29, 1895. MAIL SERVICE CAR Among the first to visit the dog upon his arrival in town was often the local reporter, eager to learn where the dog had been, and share his travels with readers. -

EA Baker Union Update

E.A. Baker Union Update ARVIN AVENAL BAKERSFIELD BORON CALIFORNIA CITY DELANO EDWARDS AFB LAMONT McFARLAND MOJAVE RIDGECREST SHAFTER TAFT TEHACHAPI TRONA WASCO CHARTERED FEBRUARY 25, 1901 Web Version AUGUST 2014 Philadelphia was an amazing experience which required a lot of energy and dedication by your Branch delegates! There are resolutions that are made from various branches across the country that Johnny are heard, debated, then voted on by your delegates. The “theme” this year was CCA’s. The CCA topic dominated most of the resolutions made. There were resolutions approved to negotiate for: CCA Sunday premium; Allow on CCA’s to carry over the maximum amount of annual leave currently 440 hours; Including CCA’s to be eligible employees to receive military pay; Allowing CCA’s to put in for mutual exchanges with other CCA’s; Allow Article 25 to ap- the ply to CCA’s for bargaining unit work (T-6 details). Please remember that these are resolutions. These are requests the membership is telling National we want them to bargain for, we still have to negotiate with Spot Postal management to get them resolved. Postmaster Donohoe is back again with his shrink to survive ideas. He now claims he has the author- ity to slow down delivery standards and thus is The 69th NALC Biannual Convention was moving forward with a plan to close 82 processing held in Philadelphia, PA from July 21st thru plants. One of those 82 is our very own Bakers- July 25, 2014. Branch 782 sent nine del- field facility. No big deal right its only clerks jobs. -

Fight for Hazard Pay Administrative Leave and Postal Funding

Communities and Postal Workers United (CPWU) SPRING 2020 -- No Closures! No Cuts! No Delay of the Mail! - www.cpwunited.com Fight for Hazard Pay Administrative Leave and Postal Funding We, the undersigned elected union representatives (shop stew- ards, alternate shop stewards, executive board members, local officers, national business agents, etc.) call on our national un- ions – APWU, NALC, NPMHU, and NRLCA – to mobilize our members and demand of the USPS and Congress: HAZARD PAY. As COVID-19 spreads across the country, the danger on the job increases exponentially. Those who con- tinue to work should be paid hazard pay. ADMINISTRATIVE LEAVE. With our lives at risk, admin- The Plan: Organizing Your istrative leave (beyond limited emergency sick leave) for all Facility for Safety vs. Covid-19* workers who need to isolate or self-quarantine instead of com- ing to work. This pandemic is similar to a community disaster, You must talk to EVERYONE about The Plan like a flood, fire, or storm, an “Act of God” as defined in USPS Find an “organizer” in each department (work sta- Employee and Labor Relations Manual, 519.21. tion, aisle, shift) Ideally, about one organizer per ten co-workers FUND THE USPS, FORGIVE THE DEBT, END THE That’s your “organizing committee” PREFUNDING MANDATE. Pass the Protect Our Post Of- Agitate – “This pandemic is life and death. If not for you, fices Act (HR 6425), which would provide $25 billion in emer- for a co-worker, for your family, for their family, for our customers” gency appropriations to the Postal Service. Eliminate the Postal Explain -- The Plan Service’s current debt. -

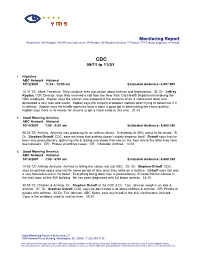

Monitoring Report I=Interview; GR=Graphic; PC=Press Conference; R=Reader; SI=Studio Interview; T=Teaser; TZ=Teased Segment; V=Visual

Monitoring Report I=Interview; GR=Graphic; PC=Press Conference; R=Reader; SI=Studio Interview; T=Teaser; TZ=Teased Segment; V=Visual CDC 09/11 to 11/01 1. Nightline ABC Network National 10/12/2001 11:35 - 12:05 am Estimated Audience: 4,997,900 15.37 TZ; More Terrorism. They continue their discussion about anthrax and bioterrorism. SI; Dr. Jeffrey Koplan, CDC Director, says they received a call from the New York City Health Department involving the NBC employee. Koplan says the woman was exposed to the contents of an ill intentioned letter and developed a skin rash and lesion. Koplan says the amount of powder matters when trying to determine if it is anthrax. Koplan says the health agencies have a done a good job in determining the cases quickly. Koplan says there is no reason for anyone to get a nasal swab at this time. 21.42 2. Good Morning America ABC Network National 10/15/2001 7:00 - 8:00 am Estimated Audience: 4,660,780 08.23 TZ; Anthrax. America was preparing for an anthrax attack. Everybody at NBC wants to be tested. SI; Dr. Stephen Ostroff, CDC, says we know that anthrax doesn't widely disperse itself. Ostroff says they've been very precautionary, gathering info & testing everybody that was on the floor where the letter may have been present. GR; Photos of anthrax cases. GR; Inhalation Anthrax. 13.04 3. Good Morning America ABC Network National 10/16/2001 7:00 - 8:00 am Estimated Audience: 4,660,780 14.50 TZ; Anthrax Analysis.