View of Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

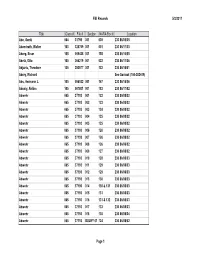

5/3/2011 FBI Records Page 1 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box

FBI Records 5/3/2011 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box # Location Abe, Genki 064 31798 001 039 230 86/05/05 Abendroth, Walter 100 325769 001 001 230 86/11/03 Aberg, Einar 105 009428 001 155 230 86/16/05 Abetz, Otto 100 004219 001 022 230 86/11/06 Abjanic, Theodore 105 253577 001 132 230 86/16/01 Abrey, Richard See Sovloot (100-382419) Abs, Hermann J. 105 056532 001 167 230 86/16/06 Abualy, Aldina 105 007801 001 183 230 86/17/02 Abwehr 065 37193 001 122 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 002 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 003 124 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 004 125 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 005 125 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 006 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 007 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 008 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 009 127 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 010 128 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 011 129 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 012 129 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 013 130 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 014 130 & 131 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 015 131 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 016 131 & 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 017 133 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 018 135 230 86/08/04 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 01 124 230 86/08/02 Page 1 FBI Records 5/3/2011 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box # Location Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 20 127 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 133 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 35 134 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 EBF 014X 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 EBF 014X 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr -

The Place of Music, Race and Gender in Producing Appalachian Space

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Geography Geography 2012 PERFORMING COMMUNITY: THE PLACE OF MUSIC, RACE AND GENDER IN PRODUCING APPALACHIAN SPACE Deborah J. Thompson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Thompson, Deborah J., "PERFORMING COMMUNITY: THE PLACE OF MUSIC, RACE AND GENDER IN PRODUCING APPALACHIAN SPACE" (2012). Theses and Dissertations--Geography. 1. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/geography_etds/1 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Geography at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Geography by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. -

Focused, Solid and Ready for Growth Annual Report 2002

Leif Leif Höegh & Co – Annual report 2002 ...focused, solid and ready for growth Annual report 2002 Leif Höegh & Co Wergelandsveien 7 P.O. Box 2596 Solli, N-0203 Oslo Phone: +47 22 86 97 00 Telex: 70935 HSHIP Fax: +47 22 20 14 08 E-mail: [email protected] www.hoegh.no Org no: 921483957 JØMERK IL ET M 241 344 Trykksaker Contents The fleet per 31.12.2002 Service Vessel LHC-share % Built Dwt Cargo capacity Service Vessel LHC-share % Built Dwt Cargo capacity Ro/Ro HUAL Trailer 100 1980 15 5935 250 Dry Bulkceu SG Prosperity 100 1996 211 202 HUAL Tramper 100 1980 12 169 3 550 ceu SG Enterprise 100 1997 211 485 HUAL Trubadour 100 1980 12 169 3 550 ceu Open Hatch Höegh Merchant 100 1977 44 895 1 724 teu HUAL Tropicana 100 1980 11 977 3 550 ceu Höegh Merit 100 1977 44 926 1 724 teu HUAL Tracer 100 1981 12 961 3 640 ceu Höegh Musketeer 100 1977 44 892 1 724 teu President’s report 1 HUAL Trapper 100 1981 12 961 3 640 ceu Höegh Marlin 100 1977 45 0631 740 teu Company profile 2 HUAL Trekker 100 1981 11 977 3 550 ceu Höegh Mascot 100 1977 45 0631 740 teu Financial summary 4 HUAL Trinity 100 1981 17 938 5 550 ceu August Oldendorff 1) 100 1979 43 571 1 492 teu Main events 5 HUAL Transit 100 1981 17 650 5 550 ceu Max Oldendorff 2) 100 1979 44 016 1 492 teu HUAL Trapeze 100 198316 694 4 110 ceu Höegh Mistral 100 1986 30 402 1 204 teu HUAL Traveller 100 1983 15 370 3 710 ceu Höegh Monal 100 1996 49 755 2 217 teu Annual report HUAL Trotter 100 1983 15 392 3 710 ceu Höegh Morus 100 1997 49 755 2 217 teu Annual report 2002 6 HUAL Trophy 100 1987 20 600 5 910 ceu -

Gravrättsinnehavare Sökes Mölltorp.Pdf

Kungörelse Vid inventering av gravplatser på Mölltorps kyrkogård har följande gravplatser befunnits sakna registrerade gravrättsinnehavare. Gravplats Senast gravsatta Plats Dödsår Uppdaterad 2021-03 G B 3-A-B Gustava Bjerstedt Johansson 1918 G B 5-A-B Karl August Kärrman 1926 G B 9-A-B Manny Hulda Maria Thübeck 1980 G B 10 Johanna Ulrika Rosalia Emilia Ewerts 1929 G B 11-A-B Astrid Matilda Ahlqvist 1974 G B12-A-B Lotta Kajsa Carlsson 1923 G B 13-A-B Malin Teresia Göransson 1916 G C 8-A_B Karolina Rantzén Krogstorp 1925 G C 10-A-B Margit Kristina Berglund Karlsborg 1982 G C 18-A-F Johanna Fredrika Andersdotter Sjövik 1939 G D 3 A-B Svea Hjelmberg 1974 G D 5 A-C-D Anders Fredrik Eriksson ”Ebbetorp” 1927 G D 12 Karolina Torstenson Skäverud 1926 G D 22 A-B Selma Andersson 1923 G E 1 A-B Rut Ingeborg Landelius 1991 G E 4 A-B Anna Karolina Holm 1944 G E 7 A-B Anna Lovisa Holmqvist 1951 G E 16 A-B Carl August Eriksson 1938 G E 18 A-B Karl Johan Jansson 1940 G F 4 A-B Tore Ragnar Lundgren 1990 G G 60 Axel Verner Johansson Älebäcken 1973 G G 106 Maria Sofia Harnesk 1929 G G 109 Karl Karlsson 1928 G G 110-111 Karl Arvid Pettersson 1979 G G 171,172 Frans Oskar Johansson Gräshult 1935 G G 215 Anders Viktor Andersson Gräshult 1931 G G 252,253 Ada Charlotta Persson Furugården 1969 G G 254,255 Jenny Paulina Persson Måsebo 1958 G G 276 Amanda Karolina Lake Furugården 1950 G G 277,278 Karl David Viselius Malm Ingesborg 1984 G G 279 Hulda Gustava Andersson 1963 G G 286 Frans Vilhelm Eriksson 1948 G G 289 Anders Martin Ljung 1967 G G 293 Gerda Hedvig Altea -

Class of 2020

Virtual Celebration and Degree Conferral for the CLASS OF 2020 Saturday, May 16, 2020 Contents Board of Visitors, 2 Administration, 3 Graduates and Degree Candidates* Graduate School of Arts & Sciences, 4 College of Arts & Sciences, 8 School of Medicine, 18 School of Law, 19 School of Engineering & Applied Science, 21 Curry School of Education and Human Development, 26 Darden Graduate School of Business Administration, 30 School of Architecture, 31 School of Nursing, 32 McIntire School of Commerce, 34 School of Continuing & Professional Studies, 36 Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy, 37 School of Data Science, 37 Student and Faculty Awards, 38 Honorary Societies, 39 The Good Old Song, 42 * The degree candidates in this program were applicants for degrees as of May 1, 2020. The August 2019 and December 2019 degree recipients precede the list of May 2020 degree candidates in each section. © 2020 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia Designed by University of Virginia Printing and Copying Services University of Virginia Board of Visitors James B. Murray, Jr., Rector (Keene, VA) Whittington W. Clement, Vice Rector (Richmond, VA) Robert M. Blue (Richmond, VA) Mark T. Bowles (Goochland, VA) L.D. Britt, M.D., MPH (Suffolk, VA) Frank M. Conner III (Alexandria, VA) Elizabeth M. Cranwell (Vinton, VA) Thomas A. DePasquale (Washington, DC) Barbara J. Fried (Crozet, VA) John A. Griffin (New York, NY) Louis S. Haddad (Suffolk, VA) Robert D. Hardie (Charlottesville, VA) Maurice A. Jones (Norfolk, VA) Babur B. Lateef, M.D. (Manassas, VA) Angela Hucles Mangano (Playa del Rey, CA) C. -

Missouri Folklore Society Journal

Missouri Folklore Society Journal Special Issue: Songs and Ballads Volumes 27 - 28 2005 - 2006 Cover illustration: Anonymous 19th-century woodcut used by designer Mia Tea for the cover of a CD titled Folk Songs & Ballads by Mark T. Permission for MFS to use a modified version of the image for the cover of this journal was granted by Circle of Sound Folk and Community Music Projects. The Mia Tea version of the woodcut is available at http://www.circleofsound.co.uk; acc. 6/6/15. Missouri Folklore Society Journal Volumes 27 - 28 2005 - 2006 Special Issue Editor Lyn Wolz University of Kansas Assistant Editor Elizabeth Freise University of Kansas General Editors Dr. Jim Vandergriff (Ret.) Dr. Donna Jurich University of Arizona Review Editor Dr. Jim Vandergriff Missouri Folklore Society P. O. Box 1757 Columbia, MO 65205 This issue of the Missouri Folklore Society Journal was published by Naciketas Press, 715 E. McPherson, Kirksville, Missouri, 63501 ISSN: 0731-2946; ISBN: 978-1-936135-17-2 (1-936135-17-5) The Missouri Folklore Society Journal is indexed in: The Hathi Trust Digital Library Vols. 4-24, 26; 1982-2002, 2004 Essentially acts as an online keyword indexing tool; only allows users to search by keyword and only within one year of the journal at a time. The result is a list of page numbers where the search words appear. No abstracts or full-text incl. (Available free at http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Search/Advanced). The MLA International Bibliography Vols. 1-26, 1979-2004 Searchable by keyword, author, and journal title. The result is a list of article citations; it does not include abstracts or full-text. -

Of Names 91, 92, 95–97 Davies, Brian 13, 49 Adorno, Theodor Wiesengrund 34, 43, 44, 90, Davis, Scott G

Davidson, Donald 9, 10, 15, 33, 59, 63, 66–84, Index of Names 91, 92, 95–97 Davies, Brian 13, 49 Adorno, Theodor Wiesengrund 34, 43, 44, 90, Davis, Scott G. 69, 74 116, 121, 123, 140, 161, 162, 213 Dawkins, Richard 16 Agamben, Giorgio 202, 207, 212 Deleuze, Giles 11, 138, 143, 208 Albinus, Lars 16, 45, 56, 59, 63, 67, 105, 137, Dennett, Daniel 16 153, 177, 179, 196, 198, 199, 202 Derrida, Jacques 15, 16, 21, 22, 152, 207–209, Alston, William 13, 28, 29, 41 212, 215 Ananda Sri G. 102 Detienne, Marcel 91–93, 99, 141 Apel, Karl Otto 15, 50, 51, 58, 169 Doležel, Lubomir 55, 155 Arendt, Hannah 104, 116, 120 Donald, Merlin 57 Aristotle 43, 66, 90–92, 94, 99, 115, 138, 158 Doniger, Wendy 198 Asad, Talal 36 Drury, M. O‘C. 127 Augustine 43, 84, 186 Duns Scotus 215 Bachelard, Gaston 8, 35 Eiland, H. 113, 114, 121, 122, 125, 128, 130 Badiou, Alain 17, 37, 41, 202 Eliade, Mircea 18, 19 Bakhtin, Mikhael M. 98, 202 Engler, Steven 6, 9, 13, 40, 63, 69, 70, 71 Barbour, Ian G. 13, 47 Feyerabend, Ludwig 15 Barnes, Barry 15 Fitzgerald, Timothy 18, 20, 36, 40, 190 Barth, Karl 142 Flood, Gavin 6, 16, 17, 20, 223 Baudelaire, Charles 118, 211 Foucault, Michel 2, 4, 8, 15, 24, 35, 38–40, 48, Bellah, Robert 40, 219 50, 51, 66, 96, 100, 128, 129, 141, 152, 195, Benjamin, Walter 2, 4, 10, 11, 33, 41, 79, 86, 202, 208, 214 89–91, 96–98, 101, 102, 105–107, 111–140, Frankenberry, Nancy 18, 66, 69–71 143–146, 148, 151, 160, 161, 167, 192, 202, Frazer, James George 83–87, 89, 108, 110, 119, 205–207, 210–213, 216–219, 222, 223 130, 132, 133, 135, 183–185, 190, 202, 213 Berger, Peter 7, 15, 80, 91 Freud, Sigmund 13, 182, 206 Bloor, David 15 Frege, Gottlob 32, 62, 144, 145 Bonhoeffer, Dietrich 142 Gabrielli, Paolo 105, 120, 123, 131, 132, 211 Borges, Luis 211, 218, 223 Gadamer, Hans Georg 37, 38, 72, 73, 156, 157 Boyer, Pascal 60, 197 Gardiner, Mark Q. -

3358 the LONDON GAZETTE, 18 JULY, 1947 Meitner, Franz Philipp

3358 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 18 JULY, 1947 Meitner, Franz Philipp. Child of Meitner,, Walter. Meyerhoff, Fritz (known as Fred Meyerhofl); Gei- Meitner, Walter; Austria; Chemist; 198, Wilmslow many; Manufacturer; 24, Colinton Mains Terrace, Road, Manchester 20. 10 June, 1947- Edinburgh 13, Midlothian, Scotland. 13 June, Melcher, Kitty Katherina; Austria; Hosiery Fore- 5947- s.- woman; 16, Portsdown Road, Leicester, Leicester- Meyerhofl, Heinz Julius (known as Henry). Child shire. 6 June, 1947. of Meyerhofl, Fritz (known as Fred Meyerhoff). Mellinger, Lucas Emmanuel Matthias; Germany; Meyerhoff, Henry. See Meyerhofl, Heinz Julius. Student; 37, Emperors Gate, London, S.W-7. 31 Meyerhoff, Peter Adolf Wilhelm; Germany; May, 1947. Economist; 17, Windmill Road, Brentford, Mellinger, Michael Andreas; Germany; Student; 66, Middlesex. 24 June, 1947. Scarsdale Villas, London, W.8. n June, 1947. Meyersohn, Herbert; Germany; Dental Surgeon; *Melzak, Ada; Poland; Supervisor; 44, Wheatlands 8, Harbord Street, London, S.W.6. 19 May, Drive, Bradford, Yorkshire. 29 May, 1947. 1947. Melzer, Leo; Austria; Technical Assistant; 132, Meyerstein, Wilhelm; Germany; Lecturer of Anson Road, London, N.W.2. 20 June, 1947- Physiology; 123, Willow Avenue, Birmingham, Mendel, Rahel Luise; Germany; Student Nurse; Warwickshire. 14 June, 1947. Withington Hospital, Nell Lane, West Didsbury, *Meyns, Christena Winifred Claudia; Germany; Manchester. 2 June, 1947. Housewife; " Ivybank," Fawkham, Kent. n Mendels, Louis Philip; Netherlands; Managing June, 1947. Director; Sea View, 26, Daglands Road, Fowey, Michaelis, Martha; Germany; Social Worker; 51, Cornwall. 20 May, 1947. Fitzjphns Avenue, London, N.W.3- 26 June, Mendelsohn, Heinrich. Child of Mendelsohn, 1947. Johannes. Michel, Stefame Caroline; Germany; Secretary; Mendelsohn, Johannes; Germany; Distiller; 8, Holm- 9, Edmunds Walk, London, N.2. -

2015 Conference

37th annual September 10–13, 2015 Thursday, September 10 Saturday, September 12 The Lyric Theatre, 300 East 3rd Street, downtown Lexington All daytime sessions are held a The Carnegie Center for Literacy and Learning, 251 West 2nd Street. 6:00–8:00 p.m. BadddDDD Sonia Sanchez: a new documentary film and conversation with Sonia Sanchez and Patrice Muhammad 8:00–9:00 a.m. Small Group Workshops, 2:00–4:15 p.m. Free and open to the public registration and complimentary continental breakfast by reservation only Writing Lives: Loud and Quiet 9:00–10:00 a.m., plenary session biography/nonfiction workshop with Emily Bingham, part 2 What I Think I’m Doing by reservation only, lower level, Sexton Room fiction craft talk by Ann Beattie Friday, September 11 open to all registrants, first floor, Stuart Room Self-Exposure vs. Self-Examination All daytime sessions are held a The Carnegie Center for Literacy and Learning, 251 West 2nd Street. workshop in memoir and personal essay 10:15 a.m.–12:30 p.m., small group workshops with Meghan Daum, part 2 by reservation only by reservation only, second floor, Allen Room The Obstructions 8:00–9:00 a.m. by reservation only workshop in poetry with Angela Ball, part 2 Road Trip: Finding Inspiration in Place registration and complimentary continental breakfast Writing Lives: Loud and Quiet by reservation only, lower level, Caudill Room workshop in playwriting with Carson Kreitzer, part 2 biography/nonfiction workshop with Emily Bingham, part 1 by reservation only, lower level, Brown Room 9:00–10:00 a.m., plenary session by reservation only, lower level, Sexton Room One Poem, Two Attitudes reading by Sonia Sanchez, with introduction and Q &A by workshop in poetry with Kathleen Driskell, part 2 From “What If?” to “What Now?” to “What Just Happened?” DaMaris Hill Self-Exposure vs. -

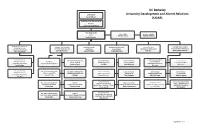

UC Berkeley University Development and Alumni Relations (UDAR)

UC Berkeley Chancellor University Development and Alumni Relations Carol Christ (UDAR) Executive Vice Chancellor & Provost Catherine Koshland Vice Chancellor Chief of Staff Executive Assistant UDAR Kim Kincannon Matthew Weinberg Julie Hooper Assistant Vice Chancellor Associate Vice Chancellor Campaign Director Associate Vice Chancellor Executive Director Associate Vice Chancellor PRINCIPAL GIFTS & CONSTITUENT PROGRAMS FOUNDATION OPERATIONS ADVANCEMENT OPERATIONS STRATEGIC INITIATIVES CAMPAIGN DEVELOPMENT Michelle McClellan Leslie Schibsted Lishelle Blakemore MiHi Ahn Nancy Lubich McKinney Christine Schmidt Executive Director Chief Technology Officer Asst. Dean of Development Executive Director Executive Director Senior Director PRINCIPAL GIFTS & 26 CAMPUS ADVANCEMENT SOCIAL SCIENCES ALUMNI RELATIONS GIFT PLANNING FUND MANAGEMENT STRATEGIC INITIATIVES Chief Development Officers INFORMATION SERVICES Christian Gordon Jay Dillon Randi Silverman Ali De Gros Jenny Cutting Karl Otto Executive Director Asst. Dean of Development Asst. Dean of Development Executive Director Executive Director Senior Director Senior Director PRINCIPAL GIFTS & ARTS & HUMANITIES UNDERGRADUATE STUDIES ANNUAL PROGRAMS MAJOR GIFTS DONOR RECOGNITION GIFT SERVICES STRATEGIC INITIATIVES Lynnette Teti VACANT Howard Heevner Tami Cardenas Katy Galli-Kreps Matthew Weaver Leti Light Executive Director Human Resources Director Asst. Dean of Development Director Executive Director Executive Director EXTERNAL RELATIONS & TALENT MANAGEMENT & BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES PROSPECT DEVELOPMENT STUDENT EXPERIENCE & DIVERSITY FINANCE & ADMINISTRATION MARKETING COMMUNICATIONS WORKFORCE PLANNING Kirsten Swan Terence Kissack Brooke Hendrickson Loraine Binion Colleen Rovetti Ron Coverson Asst. Dean of Development Director Executive Director MATH & PHYSICAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS & OUTREACH FOUNDATION RELATIONS & Maria Hjelm Carolyn Iyoya Irving CORPORATE PHILANTHROPY Sylvia Bierhuis Updated 7/1/21. -

The Real Y'alternative

v i b e s THE REAL Y’ALTERNATIVE NYC string band navigates the ebony and irony of Americana BY KANDIA CRAZY HORSE version of “Dueling Banjos (Black to the Future mix)” anytime soon. owboy Troy, the long, tall Texas country- The Ebony Hillbillies’ own extant CDs will rapper, is the nation’s leading proponent of have to tide y’all over until the eventual sepia hick-hopC — or rather the most prominent one. His twang revolution (don’t tell Diddy!). Sabrina’s heavily rotated CMT clip for the infectious, fiddle- Holiday and I Thought You Knew (forthcoming and-banjo-fueled single “I Play Chicken with the on Lincolnton-based Gaff Records) provide a Train” features a curiously integrated audience great introduction to a largely forgotten African “raising the roof” to lyrics like “I’m big and black, American cultural legacy. The trio’s take on classic clickety-clack/And I made the train jump the track black string-band repertoire includes “Cotton- like that.” A tepid rap boast, indeed. Eyed Joe,” “Sugar in the Gourd,” “Hell Among How much cooler would Cowboy Troy’s the Yearlings” and “Yellow Rose of Texas,” a tune challenge to Music Row be if he had enlisted New originating from a black minstrel show which is York’s Ebony Hillbillies, three urban hipsters who actually an ode to the singer’s “sweetest girl of play the subway stations and city streets as the self- color a fella ever knew.” proclaimed “last black string band in America”? Head Hillbilly Enrique Prince certainly has the chops to back anyone. -

1935-Commencement.Pdf

University of Minnesota COMMENCEMENT CONVOCATION WINTER QUARTER 1935 NORTHROP MEMORIAL AUDITORIUM Thursday, March 21, 1935, Eleven O'Clock PROGRAM President LOTUS D. COFFMAN, Presiding PROCESSIONAL-HMarche de Fete" - Claussmann GEORGE H. FAIRCLOUGH HYMN-HAmerica" My country! 'tis of thee Our fathers' God! to Thee, Sweet land of liberty, Author of Liberty, Of thee I sing; To Thee we sing; Land where my fathers died, Long may our land be bright Land of the Pilgrims' pride, With freedom's holy light; From every mountain side Protect us by Thy might, Let freedom ring! Great God, our King! COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS-"Telescopes, Microscopes, and Politics" THOMAS V. SMITH, Ph.D. Professor of Philosophy, University of Chicago ORGAN SOLO-"Toccata and Fugue in D Minor" Bach (Born March 21, 1685) MR. FAIRCLOUGH CONFERRING OF DEGREES LOTUS D. COFFMAN, Ph.D., LL.D. President of the University 2 SONG-"Hail, Minnesota!" Minnesota, hail to thee! Like the stream that bends to sea Hail to thee, our College dear! Like the pine that seeks the blue I Thy light shall ever be Minnesota, still for thee, A beacon bright and clear; Thy sons are strong and true. Thy sons and daughters true From thy woods and waters fair, Will proclaim thee near and far; From thy prairies waving far, They will guard thy fame At thy call they throng, And adore thy name; With their shout and song, Thou shalt be their Northern Star. Hailing thee their Northern Star. RECESSIONAL-"Finale (Symphony V)" Widor MR. FAIRCLOUGH SMOKING As a courtesy to those attending functions, and out of respect for the character of the building, be it resQlved by the Board of Regents that there be printed in the programs of .11 functions held in the Cyrus Northrup Memorial Auditorium a request that smoking be confined to the outer lobby on the main floor, to the gallery lobbies, and to the lounge rooms.