Ethnic and Racial Formation on the Concert Stage: a Comparative Analysis of Tap Dance and Appalachian Step Dance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voices of Feminism Oral History Project: Roma, Catherine

Voices of Feminism Oral History Project Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College Northampton, MA CATHERINE ROMA Interviewed by JOYCE FOLLET June 19 and 20, 2005 Northampton, Massachusetts This interview was made possible with generous support from the Ford Foundation. © Sophia Smith Collection 2006 Sophia Smith Collection Voices of Feminism Oral History Project Narrator Catherine Roma was born in Philadelphia January 29, 1948, the youngest of three children of Italian-born parents. Her mother completed high school and, once married, was a community volunteer. Her father graduated from Princeton University and Temple Law School, but when his own father died young, he left legal practice to run the family’s barbershops in Philadelphia and other East Coast railroad terminals. Practicing Catholics, Catherine’s parents sent her to Germantown Friends School K-12; she remains a Convinced Friend. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Roma earned a BA in music and an MM in Choral Conducting at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she became involved in socialist-feminist politics and began organizing a feminist choral group in 1974. Returning to Philadelphia the following year to teach music at Abington Friends School, she organized and conducted Anna Crusis, the first feminist women’s choir in the US. In 1983 she undertook the doctorate in musical arts at the University of Cincinnati, where she founded MUSE, the community chorus she continues to lead. Under Roma’s leadership, MUSE is a vital group in what has become a national and international grassroots movement of women’s choruses. MUSE is recognized as a model anti-racist community organization and a progressive force in Cincinnati politics. -

FSGW Midwinter Festival

Volume 49, Number 5 NEWSLETTERwww.fsgw.org January 2013 FSGW Midwinter Festival Takoma Park Middle School 7611 Piney Branch Rd., Silver Spring, MD Saturday, February 2, 2013 12 noon–10:30 pm Hooray! It’s time for the FSGW Mini-Fest—dancers and dumbeks, washboards and waltzing, tales and the tango, blues and ballads, morris and more! With two all-day dance tracks, and seven workshop and performance sites, plus unscheduled hallway shenanigans, there’s no shadow of a doubt that it’ll cure your winter blues!! Daytime Performance/Workshops. Check fsgw.org for updates; as of December 16, the schedule is as follows (see grid on page 27): In the Cafetorium, fabulous music programmed by Charlie Baum— Shenandoah Run at noon. Then at 1, The Chro- matics, an a cappella group with a distinctive scientific bent, followed by the versatile Capitol Hillbillies and by Sarenica’s rousing tamburitza music. Kensington Station is next, with folk music of the 60s. And lastly, the Bumper Jacksons with traditional jazz and Appalachian hollers. (Food will also be available in the Cafetorium, from noon until 7:30 pm.) The “Roots Americana” room, programmed by Emily Hilliard, opens with a Shape Note Singing, followed by a “Party at Ralph’s House” featuring Jeff Place, Smithsonian Folkways Archivist. At 2, ballads and traditional singing, and at 3 FSGW explores Foodways Traditions, a panel discussion of historic and current foods and traditions with folklorists and food producers. Also, discover what exciting new plans are developing at FSGW in the realm of food lore. End the day here with string-band music and an open jam. -

GIRL with a CAMERA a Novel of Margaret Bourke-White

GIRL WITH A CAMERA A Novel of Margaret Bourke-White, Photographer Commented [CY1]: Add Photographer? By Carolyn Meyer Carolyn Meyer 100 Gold Avenue SW #602 Albuquerque, NM 87102 505-362-6201 [email protected] 2 GIRL WITH A CAMERA Sometime after midnight, a thump—loud and jarring. A torpedo slams into the side of our ship, flinging me out of my bunk. The ship is transporting thousands of troops and hundreds of nurses. It is December 1942, and our country is at war. I am Margaret Bourke-White, the only woman photographer covering this war. The U.S. Army Air Forces has handed me a plum assignment: photographing an Allied attack on the Germans. I wanted to fly in one of our B-17 bombers, but the top brass ordered me to travel instead in the flagship of a huge convoy, headed from England through the Straits of Gibraltar towards the coast of North Africa. It would be safer than flying, the officers argued. As it turns out, they were dead wrong. Beneath the surface of the Mediterranean, German submarines glide, silent and lethal, stalking their prey. One of their torpedoes has found its mark. I grab my camera bag and one camera, leaving everything else behind, and race to the bridge. I hear the order blare: Abandon ship! Abandon ship! There is not enough light and not enough time to take photographs. I head for Lifeboat No. 12 and board with the others assigned to it, mostly nurses. We’ve drilled for it over and over, but this is not a drill. -

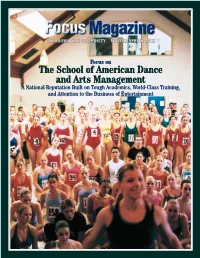

Focus Winter 2002/Web Edition

OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY • WINTER/SPRING 2002 Focus on The School of American Dance and Arts Management A National Reputation Built on Tough Academics, World-Class Training, and Attention to the Business of Entertainment Light the Campus In December 2001, Oklahoma’s United Methodist university began an annual tradition with the first Light the Campus celebration. Editor Robert K. Erwin Designer David Johnson Writers Christine Berney Robert K. Erwin Diane Murphree Sally Ray Focus Magazine Tony Sellars Photography OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY • WINTER/SPRING 2002 Christine Berney Ashley Griffith Joseph Mills Dan Morgan Ann Sherman Vice President for Features Institutional Advancement 10 Cover Story: Focus on the School John C. Barner of American Dance and Arts Management Director of University Relations Robert K. Erwin A reputation for producing professional, employable graduates comes from over twenty years of commitment to academic and Director of Alumni and Parent Relations program excellence. Diane Murphree Director of Athletics Development 27 Gear Up and Sports Information Tony Sellars Oklahoma City University is the only private institution in Oklahoma to partner with public schools in this President of Alumni Board Drew Williamson ’90 national program. President of Law School Alumni Board Allen Harris ’70 Departments Parents’ Council President 2 From the President Ken Harmon Academic and program excellence means Focus Magazine more opportunities for our graduates. 2501 N. Blackwelder Oklahoma City, OK 73106-1493 4 University Update Editor e-mail: [email protected] The buzz on events and people campus-wide. Through the Years Alumni and Parent Relations 24 Sports Update e-mail: [email protected] Your Stars in action. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Students Help Peers Presidents Sunday and Gave Her Information

Eastern Illinois University The Keep February 2007 2-2-2007 Daily Eastern News: February 02, 2007 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2007_feb Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: February 02, 2007" (2007). February. 2. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2007_feb/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2007 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in February by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "TELL THE TRUTH AND DON'T BE AFRAID." W\NVV.DENNEWS.COM Student roduction crew to learn from ESPN2 Eastern's event staff scurries angles and inserting game stats National coverage of from one end of the gym to the and other graphics onto viewers' basketball game lets other with chairs and ladders, while televisions all with the push of a students with WEIU-TV duct tape button. WEIU employees work down the colored cables. Price transferred here from Everyone is busy and the Southern Illinois University with professionals preparation is a game in its own this year to study corporate right: Be ready before tip off. communications. By Sarah Whitney For the 12th time, Lantz Arena But Saturday, Price won't attend Senior Reporter will transform from a recreational the game as a WEIU-TV employee, gymnasium into an official N CAA but as an employee for ESPN 2. A basketball game begins before basketball arena on Saturday For the first time in Eastern's tipoff. night. history, a men's basketball game Gray curtains sweep back to Saturday's game will be no will air on ESPN2. -

MVP Packet 7.Pdf

Musical Visual Packet A tournament by the Purdue University Quiz Bowl Team Questions by Drew Benner, John Petrovich, Patrick Quion, Andrew Schingel, Lalit Maharjan, Pranav Veluri, and Ben Dahl ROUND 7: Finale 1) In a musical production choreographed by John Heginbotham, this scene introduces an electric guitar to the acoustic score and during it, boots fall from the rafters one by one. Gabrielle Hamilton stars in this scene in a revival that has it performed by a single dancer, barefoot, in a modern style. The film version of this scene has a tornado roaring in the background, while Susan Stroman’s choreography for this scene has the main cast perform it themselves, instead of having trained dancers play (*) avatars of them. This sequence occurs after a character consumes the “Elixir of Egypt,” and it begins with a cheerful wedding that changes tone when the bride realizes two men have suddenly switched characters. Originally choreographed by Agnes de Mille, this revolutionary scene is regarded as the first dance sequence in a musical to incorporate plot. For ten points, name this fantasy sequence from a Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, where Laurey struggles choosing between Jud and Curly after taking a sleeping drug. ANS: the dream ballet from Oklahoma! (prompt on partial, ask for “from what musical” if just dream ballet is given) <Musicals | Quion> 2) For one show, this composer created polyphonic chants in the fictional Zentraedi language and songs for the pop star Sharon Apple. Sound engineer Rudy Van Gelder, famous for recording albums like Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, recorded this composer’s tracks for their most famous show. -

NOTICE! Land in Batavia Tomorrow

k: ■ ■ Ss T H U R SD A Y , N O VE M B ER 8,194 ' ■) . PAlit: FOUBTEEM Manchester Evening Herald Average Daily Circulation The Weather For the Moath ot October, 1945 Fsreeaet off U. 8. Weathor niroaii A public card party will be held ments. The necessity fo r that Mrs, John M. Connolly and Homemakers and others in this ’stand-by” basis seems now to Otoudy with showers tonight and vicinity are reminded of the lec tomorrow evening In the Bucking 8,995^ young son, who have been making Blood Donor have definitely dlaappeared, and, aa Saturday; eolder Saturday. About Towii ture-demonstration on Frozen ham church. The service at the Member of the Audit their home with Mrs. Connolly’s church Sunday morning will be a result, the existence o f the Man parents Mr. and Mrs. D. I. August Foods and types of Freezing Bureau ot Circulations omitted, and Instead will be held chester Red Cross Blood Donor r r s U P TO u s . to keep It In good arorldng order, f Sgt. t«eon 8. Cl«*«ynaki( of 12 of SOsWllllam street, have moved equipment, "tomorrow afternoon at Service Ends Service has been terminated. The Manchester— A City of Viiiage Charm 1:30 at the Wapplng Community at eigh t, o’clock In the evening, Sclentlfle Servicing does the trick. Call ns; We are ■ WMtfleld atreet, who for the p « t to wyhnefleld, Pennsylvania, resignatlona of the co-chairmen of trained and'eqnlpped to servlee home anlts or larger House. 'The principal speaker will when Chaplain Dudley Burr will : *7 month! hm! served tn the Army where they V lll make their home. -

Compton Music Stage

COMPTON STAGE-Saturday, Sept. 18, FSU Upper Quad 10:20 AM Bear Hill Bluegrass Bear Hill Bluegrass takes pride in performing traditional bluegrass and gospel, while adding just the right mix of classic country and comedy to please the audience and have fun. They play the familiar bluegrass, gospel and a few country songs that everyone will recognize, done in a friendly down-home manner on stage. The audience is involved with the band and the songs throughout the show. 11:00 AM The Jesse Milnes, Emily Miller, and Becky Hill Show This Old-Time Music Trio re-envisions percussive dance as another instrument and arrange traditional old-time tunes using foot percussion as if it was a drum set. All three musicians have spent significant time in West Virginia learning from master elder musicians and dancers and their goal with this project is to respect the tradition the have steeped themselves in while pushing the boundaries of what old-time music is. 11:45 AM Ken & Brad Kolodner Quartet Regarded as one of the most influential hammered dulcimer players, Baltimore’s Ken Kolodner has performed and toured for the last ten years with his son Brad Kolodner, one of the finest practitioners of the clawhammer banjo, to perform tight and musical arrangements of original and traditional old-time music with a “creative curiosity that lets all listeners know that a passion for traditional music yet thrives in every generation (DPN).” The dynamic father-son duo pushes the boundaries of the Appalachian tradition by infusing their own brand of driving, innovative, tasteful and unique interpretations of traditional and original fiddle tunes and songs. -

…But You Could've Held My Hand by Jucoby Johnson

…but you could’ve held my hand By JuCoby Johnson Characters Eddie (He/Him/His)- Black Charlotte/Charlie (They/Them/Theirs)- Black Marigold (She/Her/Hers)- Black Max (He/Him/His)- Black Setting The past and present. Author’s Notes Off top: EveryBody in this play is Black. I strongly encourage anyone casting this play to avoid getting bogged down in a narrow understanding of blackness or limit themselves to their own opinions on what it means to be black. Consider the full spectrum of Blackness and what you will find is the full spectrum of humanity. One character in this play is gender non-binary. I encourage people to fill the role with an actor who is also gender non-binary. I also urge people not to stop there. Consider trans performers for any and all roles. This play can only benefit from their presence in the room. The ages of the actors don’t need to match the ages of the characters. I would actually encourage an ensemble of all different ages. As we play with time in this play, this will open us up to possibilities that extend beyond realism or any other genre. Speaking of genre, my only request is that the play be theatrical. Whatever that means to you. This is not realism, or naturalism, or expressionism, or any other ism. Forget all about genre. All that to say: Be Bold. Have fun. Lead with love. 2 “Love is or it ain’t. Thin love ain’t love at all.” -Toni Morrison 3 A Beginning Darkness. -

Reggie Workman Working Man

APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM REGGIE WORKMAN WORKING MAN JIM JONNY RICHARD EDDIE McNEELY KING WYANDS JEFFERSON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JIM Mcneely 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JONNY KING 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : REGGIE WORKMAN 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : RICHARD WYANDS by marilyn lester Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest WE Forget : EDDIE JEFFERSON 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : MINUS ZERO by george grella US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviews 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne