COSMOS an D HISTORY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

2 (2015) Miscellaneous 1: A-N Biographical Metamorphoses in the History of Religion Moshe Idel and Three Aspects of Mircea Eliade EDUARD IRICINSCHI Käte Hamburger Kolleg “Dynamics in the History of Religions between Asia and Europe”, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Germany © 2015 Ruhr-Universität Bochum Entangled Religions 2 (2015) ISSN 2363-6696 http://dx.doi.org./10.13154/er.v2.2015.A–N Biographical Metamorphoses in the History of Religion Biographical Metamorphoses in the History of Religion Moshe Idel and Three Aspects of Mircea Eliade EDUARD IRICINSCHI Ruhr-Universität Bochum ABSTRACT This paper includes an extended review of Moshe Idel’s Mircea Eliade: From Magic to Myth (New York: Peter Lang, 2014) through a triple analysis of Eliade’s early literary, epistolary, and academic texts. The paper examines Idel’s analysis of some important themes in Eliade’s research, such as his shift from understanding religion as magic to its interpretation as myth; the conception of the camouflage of sacred; the notions of androgyny and restoration; and also young Eliade’s theories of death. The paper also discusses Idel’s evaluation of Eliade’s programatic misunderstanding of Judaism and Kabbalah, and also of Eliade’s moral and professional abdication regarding the political and religious aspect of the Iron Guard, a Romanian nationalist extremist and anti-Semitic group he was affiliated with in 1930s. KEY WORDS Mircea Eliade; Moshe Idel; history of religion; magic; myth; sacred and profane; the Iron Guard Gershom Scholem sent Mircea Eliade a rather personal letter on June 6, 1972. The two famous historians of religion met with a certain regularity, between 1950 and 1967, at various summer Eranos meetings in Ascona, Switzerland, for interdisciplinary conferences initially organized under the guidance of Carl G. -

Voronina, "Comments on Krzysztof Michalski's the Flame of Eternity

Volume 8, No 1, Spring 2013 ISSN 1932-1066 Comments on Krzysztof Michalski's The Flame of Eternity Lydia Voronina Boston, MA [email protected] Abstract: Emphasizing romantic tendencies in Nietzsche's philosophy allowed Krzysztof Michalski to build a more comprehensive context for the understanding of his most cryptic philosophical concepts, such as Nihilism, Over- man, the Will to power, the Eternal Return. Describing life in terms of constant advancement of itself, opening new possibilities, the flame which "ignites" human body and soul, etc, also positioned Michalski closer to spirituality as a human condition and existential interpretation of Christianity which implies reliving life and death of Christ as a real event that one lives through and that burns one's heart, i.e. not as leaned from reading texts or listening to a teacher. The image of fire implies constant changing, unrest, never-ending passing away and becoming phases of reality and seems losing its present phase. This makes Michalski's perspective on Nietzsche and his existential view of Christianity vulnerable because both of them lack a sufficient foundation for the sustainable present that requires various constants and makes it possible for life to be lived. Keywords: Nietzsche, Friedrich; life; eternity; spontaneity; spirituality; Romanticism; existential Christianity; death of God; eternal return; overman; time; temporality. People often say that to understand a Romantic you have occurrence of itself through the eternal game of self- to be even a more incurable Romantic or to understand a asserting forces, becomes Michalski's major explanatory mystic you have to be a more comprehensive mystic. -

Sanatana-Dharma

BASICS OF SANATANA DHARMA YUGAS • Satya Yuga (also known as Krita Yuga "Golden Age"): • The first and best Yuga. It was the age of truth and perfection. • Humans were gigantic, powerfully built, handsome, honest, youthful, vigorous, erudite and virtuous. The Vedas were one. All mankind could attain to supreme blessedness. • There was no agriculture or mining as the earth yielded those riches on its own. • Weather was pleasant and everyone was happy. There were no religious sects. There was no disease, decrepitude or fear of anything. • Human lifespan was 100,000 years and humans tended to have hundreds or thousands of sons or daughters. • People had to perform penances for thousands of years to acquire Samadhi and die. • Matsya, Kurma, Varaha and Narasimha are the four avatars of Vishnu in this yuga. • Treta Yuga: • Is considered to be the second Yuga in order, however Treta means the "Third". • In this age, virtue diminishes slightly. • At the beginning of the age, many emperors rise to dominance and conquer the world. Wars become frequent and weather begins to change to extremities. • Oceans and deserts are formed. • People become slightly diminished compared to their predecessors. • Agriculture, labor and mining become existent. Average lifespan of humans is around 1000- 10,000 years. • Vamana, ParasuRama, and Sri RamaChandra are the three avatars of Vishnu in Treta Yuga. • Dvapara Yuga: • Is considered to be the third Yuga in order. • Dvapara means "two pair" or "after two". • In this age, people become tainted with Tamasic qualities and aren't as strong as their ancestors. • Diseases become rampant. -

Welcome to the Great Ring

Planescape Campaign Setting Chapter 1: Introduction Introduction Project Managers Ken Marable Gabriel Sorrel Editors Gabriel Sorrel Sarah Hood Writers Gabriel Sorrel Sarah Hood Layout Sarah Hood 1 There hardly seem any words capable of expressing the years of hard work and devotion that brings this book to you today, so I will simply begin with “Welcome to the planes”. Let this book be your doorway and guide to the multiverse, a place of untold mysteries, wonders the likes of which are only spoken of in legend, and adventurers that take you from the lowest depths of Hell to the highest reaches of Heaven. Here in you will leave behind the confines and trappings of a single world in order to embrace the potential of infinity and the ability to travel Introduction wherever you please. All roads lie open to planewalkers brave enough to explore the multiverse, and soon you will be facing wonders no ordinary adventure could encompass. Consider this a step forward in your gaming development as well, for here we look beyond tales of simple dungeon crawling to the concepts and forces that move worlds, make gods, and give each of us something to live for. The struggles that define existence and bring opposing worlds together will be laid out before you so that you may choose how to shape conflicts that touch millions of lives. Even when the line between good and evil, lawful and chaotic, is as clear as the boundaries between neighboring planes, nothing is black and white, with dark tyrants and benevolent kings joining forces to stop the spread of anarchy, or noble and peasant sitting together in the same hall to discuss shared philosophy. -

Planescape Part One: Sigil by Cutter

Planescape Part One: Sigil By Cutter Welcome to Sigil, the City of Doors! The centre of the Planes and the local multiverse too. Sitting on the inside of a giant torus that itself floats above an infinitely tall mountain at the centre of the very plane of neutrality itself – the Concordant Domains of the Outlands. Here neutrality is enforced. Gods are barred from the city, and the Lady of Pain takes very aggressive steps to make sure nobody drags Sigil into the troubles outside. It is even a haven from the Blood War. Unfortunately, this means many, many criminals and troublemakers from outside land come here as a last resort. ‘Course, not everyone’s here of their own free choice. Sigil’s ridded in doors to other planes, and sometimes a local from outside falls in. What got them in Sigil rarely is what gets them out of Sigil, and they’re stuck here until they find a door back home. These planar doors all throughout Sigil would make it the most valuable place in the multiverse to hold. Master Sigil, you can master the Planes. But the Lady won’t let that happen. Piss her off and the best thing you can hope for is being locked in an extradimensional maze unable to die of age, hunger, or thirst. The unlucky ones get flayed alive in an instant. But on the bright side, you’ll see all kinds of things in Sigil. A devil and a demon (don’t call ‘em that, trust me) having friendly drinks in a bar. -

INTUITION .THE PHILOSOPHY of HENRI BERGSON By

THE RHYTHM OF PHILOSOPHY: INTUITION ·ANI? PHILOSO~IDC METHOD IN .THE PHILOSOPHY OF HENRI BERGSON By CAROLE TABOR FlSHER Bachelor Of Arts Taylor University Upland, Indiana .. 1983 Submitted ~o the Faculty of the Graduate College of the · Oklahoma State University in partial fulfi11ment of the requirements for . the Degree of . Master of Arts May, 1990 Oklahoma State. Univ. Library THE RHY1HM OF PlllLOSOPHY: INTUITION ' AND PfnLoSOPlllC METHOD IN .THE PHILOSOPHY OF HENRI BERGSON Thesis Approved: vt4;;. e ·~lu .. ·~ests AdVIsor /l4.t--OZ. ·~ ,£__ '', 13~6350' ii · ,. PREFACE The writing of this thesis has bee~ a tiring, enjoyable, :Qustrating and challenging experience. M.,Bergson has introduced me to ·a whole new way of doing . philosophy which has put vitality into the process. I have caught a Bergson bug. His vision of a collaboration of philosophers using his intuitional m~thod to correct, each others' work and patiently compile a body of philosophic know: ledge is inspiring. I hope I have done him justice in my description of that vision. If I have succeeded and that vision catches your imagination I hope you Will make the effort to apply it. Please let me know of your effort, your successes and your failures. With the current challenges to rationalist epistemology, I believe the time has come to give Bergson's method a try. My discovery of Bergson is. the culmination of a development of my thought, one that started long before I began my work at Oklahoma State. However, there are some people there who deserv~. special thanks for awakening me from my ' "''' analytic slumber. -

Duration, Temporality and Self

Duration, Temporality and Self: Prospects for the Future of Bergsonism by Elena Fell A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire 2007 2 Student Declaration Concurrent registration for two or more academic awards I declare that white registered as a candidate for the research degree, I have not been a registered candidate or enrolled student for another award of the University or other academic or professional institution. Material submitted for another award I declare that no material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award and is solely my own work Signature of Candidate Type of Award Doctor of Philosophy Department Centre for Professional Ethics Abstract In philosophy time is one of the most difficult subjects because, notoriously, it eludes rationalization. However, Bergson succeeds in presenting time effectively as reality that exists in its own right. Time in Bergson is almost accessible, almost palpable in a discourse which overcomes certain difficulties of language and traditional thought. Bergson equates time with duration, a genuine temporal succession of phenomena defined by their position in that succession, and asserts that time is a quality belonging to the nature of all things rather than a relation between supposedly static elements. But Rergson's theory of duration is not organised, nor is it complete - fragments of it are embedded in discussions of various aspects of psychology, evolution, matter, and movement. My first task is therefore to extract the theory of duration from Bergson's major texts in Chapters 2-4. -

PSCS Chapter 8

Planescape Campaign Setting DM’s Dark Chapter 9: DM’s Dark Project Managers Sarah Hood Editors Gabriel Sorrel Sarah Hood Andy Click Writers Janus Aran Dhampire Orroloth Rip Van Wormer Chef‘s Slaad Nerdicus Bret Smith Charlie Hoover Galen Musbach W. Alexander Michael Mudsif Simson Leigh Smeazel Mitra Salehi Sarah Hood Layout Sarah Hood 1 Well, by now a canny cutter like yourself is itching to gather your favorite victi—ahem—players, and start running a game. Of course, if you‘re completely green to the task you could always use a little bit of advice on where to start. And if you‘re old-hat, a little bit of a refresh DM’s Dark couldn‘t hurt, now could it? This chapter of the PSCS aims to help any new GMs out there who don‘t have anyone locally they can turn to for advice on some of the common or stereotypical problems with a planar game. We‘ve tried to cover the major ‗issues‘ that creep up for bashers lost in a sea of clueless, and of course if you have a question that isn‘t answered here, please feel free to drop by Planewalker.com and we‘ll be glad to give some extra advice. Preparing the Game Starting advice for a Planescape campaign is the same as it is for any other game really: Define what sort of a campaign you‘re looking to run. A planar campaign can have as wide or as narrow a scope as you like, and any sort of tone that you care to adopt. -

Evaluating Near-Death Testimony: a Challenge for Theology' Carol G

Evaluating Near-Death Testimony: A Challenge for Theology' Carol G. Zaleski Committee on the Study of Religion Harvard University ABSTRACT In nearly every culture, people have told stories of visionary journey to other worlds, in which an individual dies, enters the afterlife, and-by divine decree or medical prodigy-comes back to life. The return-from-death story has a long history in Western culture, developing within the apocalyptic traditions of late antiquity, flourishing in the medieval Christian vision narratives that inspired Dante's Divine Comedy, and re-emerging today in reports of near-death ex periences (NDEs). Evaluating the literature of NDEs is a task for historians of religion and theologians as well as psychologists. On the basis of a comparative study of medieval and contemporary accounts, this article proposes a nonreduc tionist interpretation, showing that it is possible to give credit to individual testimony while still taking into account the physiological, psychological, and cultural conditions that influence visionary experience in the face of death. In nearly all cultures, people have told stories of travel to another world, in which a hero, shaman, prophet, king, or ordinary mortal passes through the gates of death and returns with a message for the living. In its most familiar form, this journey is a descent into the underworld. Countless figures of myth, sacred history, and literature are said to have ventured underground to the kingdom of death, to rescue its shadowy captives or to learn its secrets. The voyage to the underworld-portrayed in religious epics and enacted in rituals, dramas and games-is often associated with in itiatory death and rebirth. -

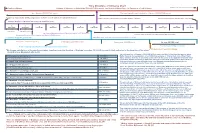

Time Structure of Universe Chart

Time Structure of Universe Chart Creation of Universe Lifespan of Universe - 1 Maha Kalpa (311.040 Trillion years, One Breath of Maha-Visnu - An Expansion of Lord Krishna) Complete destruction of Universe Age of Universe: 155.52197 Trillion years Time remaining until complete destruction of Universe: 155.51803 Trillion years At beginning of Brahma's day, all living beings become manifest from the unmanifest state (Bhagavad-Gita 8.18) 1st day of Brahma in his 51st year (current time position of Brahma) When night falls, all living beings become unmanifest 1 Kalpa (Daytime of Brahma, 12 hours)=4.32 Billion years 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas 1 Manvantara 306.72 Million years Age of current Manvantara and current Manu (Vaivasvata): 120.533 Million years Time remaining for current day of Brahma: 2.347051 Billion years Between each Manvantara there is a juncture (sandhya) of 1.728 Million years 1 Chaturyuga (4 yugas)=4.32 Million years 28th Chaturyuga of the 7th manvantara (current time position) Satya-yuga (1.728 million years) Treta-yuga (1.296 million years) Dvapara-yuga (864,000 years) Kali-yuga (432,000 years) Time remaining for Kali-yuga: 427,000 years At end of each yuga and at the start of a new yuga, there is a juncture period 5000 years (current time position in Kali-yuga) "By human calculation, a thousand ages taken together form the duration of Brahma's one day [4.32 billion years]. -

Implicit Theories of Friendships: Examining the Roles of Growth and Destiny Beliefs in Children's Friendships a DISSERTATION

Implicit Theories of Friendships: Examining the Roles of Growth and Destiny Beliefs in Children’s Friendships A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sara Gayle Kempner IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY W. Andrew Collins, Ph.D., Nicki R. Crick, Ph.D. August 2008 © Sara Gayle Kempner 2008 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisors, Andy Collins and Nicki Crick. Andy, thank you for being a mentor and advisor to me and supporting the development of my interests. Your continuing dedication to my education means so much to me. Nicki, you welcomed me into your lab and allowed me to broaden my research experiences. I am grateful for your nurturance and support. I would like to thank my committee members Richard Weinberg and Jeffry Simpson. Rich, you have been a great supporter of all my interests in graduate school. Jeff, it was in your close relationships seminar where the ideas for this project first emerged. Thank you for being a part of this project. I owe a great deal of gratitude to the schools, teachers, and children who participated in this study and shared their thoughts with me. Especially one child who asked me how I was going to use their answers to get a Ph.D. After explaining that I would put their answers into a computer, analyze it, and write a paper the child remarked, “Well that sounds pretty easy!” I would like to thank all the undergraduates who helped collect and enter data. -

Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, and the Horror of Existence Philip J

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Philosophy College of Arts & Sciences Spring 2007 Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, and the Horror of Existence Philip J. Kain Santa Clara University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/phi Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Kain, P. J. "Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, and the Horror of Existence," The ourJ nal of Nietzsche Studies, 33 (2007): 49-63. Copyright © 2007 The eP nnsylvania State University Press. This article is used by permission of The eP nnsylvania State University Press. http://doi.org/10.1353/nie.2007.0007 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, and the Horror of Existence PHILIP J. KAIN I t the center ofNietzsche's vision lies his concept of the "terror and horror A of existence" (BT 3). As he puts it in The Birth of Tragedy: There is an ancient story that King Midas hunted in the forest a long time for the wise Silenus, the companion of Dionysus .... When Silenus at last fell into his hands, the king asked what was the best and most desirable of all things for man. Fixed and immovable, the demigod said not a word, till at last, urged by the king, he gave a shrill laugh and broke out into these words: "Oh, wretched ephemeral race, children of chance and misery, why do you compel me to tell you what it would be most expedient for you not to hear? What is best of all is utterly beyond your reach: not to be born, not to be, to be nothing.