Modernist Sculpture and the Maternal Body

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Explosion of Modernism Transcript

The Explosion of Modernism Transcript Date: Wednesday, 19 October 2011 - 1:00PM Location: Museum of London 19 October 2011 Christian Faith and Modern Art The Explosion of Modernism The Rt Revd Lord Harries Prologue Christian art once provided a shared “symbolic order” (Peter Fuller). Shared narratives and recognised images through which the deeper meaning of life could be explored. This has gone. “The disassociation between art and faith is not written in stone but is not easy to overcome”. Formidable obstacles: of style-how to avoid pastiche, images that have gone stale-overwhelming plurality of styles, so artist has to choose-forced to choose a private language, and so lose some of the audience. [1] David Jones, particularly aware of this. Human beings are essentially sign makers. Most obviously we give someone a bunch of flowers or a kiss as a sign. So what are works of art a sign of? Here we come across the great crisis with which Jones wrestled both in his writing and his art. For he believed, and he said this view was shared by his contemporaries in the 1930’s, that the 19th century experienced what he called “The Break”.[2] By this he meant two things. First, the dominant cultural and religious ideology that had unified Europe for more than a 1000 years no longer existed. All that was left were fragmentary individual visions. Secondly, the world is now dominated by technology, so that the arts seem to be marginalised. They are no use in such a society, and their previous role as signs no longer has any widespread public resonance. -

JACOB EPSTEIN EXHIBIT at FERMILAB an Exhibition of 31 of the Sculptures of Sir Jacob Epstein, American-Born English Sculptor, Wi

~ I fermi national accelerator laboratory Operated by Universities Research Association Inc. Under Contract with the Energy Research & Development Administration Vol. 7 No. 16 April17, 1975 SCULPTURES BY JACOB EPSTEIN JACOB EPSTEIN EXHIBIT AT FERMILAB An exhibition of 31 of the sculptures of Sir Jacob Epstein, American-born English sculptor, will be at Fermilab through May 9. The exhibit is lo cated in the lounge on the second floor of the Central Laboratory. It is on loan from the Museum of African Art, Washington, D.C. The exhibition will be open to the public from 1-5 p.m. on Satur day, April 26 and Sunday, April 27. Jacob Epstein was born on Manhattan's lower East Side in 1880. His earliest sketches were of people in his neighborhood. In 1901 he was asked to illustrate Hapgood's classic book, The Spirit ... Third Portrait of Kathleen, Ralph of the Ghetto. With the proceeds of this work he Vaughan Williams, Second Portrait of sailed to Paris where he studied for three years Esther, T.S. Eliot, Third Portrait of before moving to London. He became a British Dolores ... subject in 1910; he was knighted in 1954. A prolific artisan, he produced literally hundreds of works before his death in 1959. Information about the sculptures accompanying the exhibit points out that Epstein remained com mitted throughtout his career to naturalistic depiction of the human figure. This humanist bias led him to devote a major portion of his time to non-commissioned portraits of family members or favorite models. These he undertook partly for the challenges inherent in modelling or structuring a particular face and head. -

WE the Moderns' Teachers' Pack Kettle's Yard, 2007 WE the Moderns: Gaudier and the Birth of Modern Sculpture

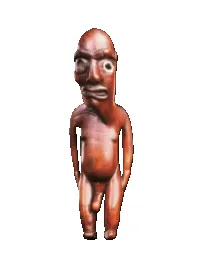

'WE the Moderns' Teachers' Pack Kettle's Yard, 2007 WE the moderns: Gaudier and the birth of modern sculpture 20 January - 18 March 2007 Information for teachers • What is the exhibition about? 2 • Key themes 3 • Who was Gaudier? 4 • Gaudier quotes 5 • Points of discussion 6 • Activity sheets 7-11 • Brief biography of the artists 12-18 1 'WE the Moderns' Teachers' Pack Kettle's Yard, 2007 What is the exhibition about? "WE the moderns: Gaudier-Brzeska and the birth of modern sculpture", explores the work of the French sculptor in relation to the wider continental context against which it matured. In 1911, aged 19, Gaudier moved to London. There he was to spend the rest of his remarkably concentrated career, which was tragically cut short by his death in the trenches four years later. These circumstances have granted the sculptor a rather ambiguous position in the history of art, with the emphasis generally falling on his bohemian lifestyle and tragic fate rather than on his artistic achievements, and then on his British context. The exhibition offers a fresh insight into Gaudier's art by mapping its development through a selection of works (ranging from sculptures and preparatory sketches to paintings, drawings from life, posters and archival material) aimed at highlighting not only the influences that shaped it but also striking affinities with contemporary and later work which reveal the artist's modernity. At the core of the exhibition is a strong representation of Gaudier's own work, which is shown alongside that of his contemporaries to explore themes such as primitivism, artists' engagement with the philosophy of Bergson, the rendition of movement and dynamism in sculpture, the investigation into a new use of space through relief and construction by planes, and direct carving. -

Memorandum To: Colleagues From: Peter Levine (405-4767)

Memorandum To: Colleagues From: Peter Levine (405-4767) Re: CP4 Workshop April 23, 2001 Attached is the paper for the next CP4 workshop: "Public Art, Public Outcry: The Scandalous Sculptures of Jacob Epstein and Richard Serra" Caroline Levine, English Department, Rutgers University/Camden May 3, 12:30 to 2pm, in the Humanities Dean's Conference Room, 1102 Francis Scott Key Hall Abstract: What kind of art belongs in public spaces? Who speaks for the “public” in controversies over public space? In 1925, Rima, a sculpture by Jacob Epstein, was installed in Hyde Park in London. An avant-garde relief, the sculpture became the focus of public controversy for almost a decade—both reviled and defended in the tabloids, disparaged in the House of Commons, extolled by art critics, and defaced three times by vandals who scrawled “Jew” and “Bolshevist” across it. Taken by some as a proof of England's innovative role in the art world and by others as the subversive work of a foreigner, Rima became the emblem of a dispute over the national character of British art. Sixty years later and across the ocean, a comparable quarrel played itself out, and this time with more troubling consequences for the art work. In the early 1980s, Richard Serra's sculpture, Tilted Arc, appeared in Federal Plaza in New York City. It was a tall, curving steel wall that bisected the plaza, transforming the public space—and, some said, ruining it for the public. Protests became increasingly forceful, and eventually, after a hearing, the sculpture was demolished. Tilted Arc, like Rima, came to embody competing ideas of the community that had allowed the object to enter its space. -

The Interwar Years,1930S

A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN This two-hour talk is part of a series of twenty talks on the works of art displayed in Tate Britain, London, in June 2017. Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain. References and Copyright • The talk is given to a small group of people and all the proceeds, after the cost of the hall is deducted, are given to charity. • My sponsored charities are Save the Children and Cancer UK. • Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain and the Tate’s online notes, display captions, articles and other information are used. • Each page has a section called ‘References’ that gives a link or links to sources of information. • Wikipedia, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Khan Academy and the Art Story are used as additional sources of information. • The information from Wikipedia is under an Attribution-Share Alike Creative Commons License. • Other books and articles are used and referenced. • If I have forgotten to reference your work then please let me know and I will add a reference or delete the information. 1 A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN • The Aesthetic Movement, 1860-1880 • Late Victorians, 1880-1900 • The Edwardians, 1890-1910 • The Great War and After, 1910-1930 • The Interwar Years, 1930s • World War II and After, 1940-1960 • Pop Art & Beyond, 1960-1980 • Postmodern Art, 1980-2000 • The Turner Prize • Summary West galleries are 1540, 1650, 1730, 1760, 1780, 1810, 1840, 1890, 1900, 1910 East galleries are 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 Turner Wing includes Turner, Constable, Blake and Pre-Raphaelite drawings Agenda 1. -

Sculpture and Modernity in Europe, 1865-1914

ARTH 17 (02) S c u l p t u r e a n d M o d e r n i t y i n E u r o p e , 1 8 6 5 - 1 9 1 4 Professor David Getsy Department of Art History, Dartmouth College Spring 2003 • 11 / 11.15-12.20 Monday Wednesday Friday / x-hour 12.00-12.50 Tuesday office hours: 1.30-3.00 Wednesday / office: 307 Carpenter Hall c o u r s e d e s c r i p t i o n This course will examine the transformations in figurative sculpture during the period from 1865 to the outbreak of the First World War. During these years, sculptors sought to engage with the rapidly evolving conditions of modern society in order to ensure sculpture’s relevance and cultural authority. We will examine the fate of the figurative tradition in the work of such sculptors as Carpeaux, Rodin, Leighton, Hildebrand, Degas, Claudel, and Vigeland. In turn, we will evaluate these developments in relation to the emergence of a self-conscious sculptural modernism in the work of such artists as Maillol, Matisse, Brancusi, Gaudier-Brzeska, and Picasso. In addition to a history of three-dimensional representation in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, this course will also introduce the critical vocabularies used to evaluate sculpture and its history. s t r u c t u r e o f t h e c o u r s e Each hour session will consist of lectures and discussions of images, texts, and course themes. -

Sir Jacob Epstein

Former building of the British Medical Association, with sculptures by Sir Jacob Epstein. 1930. Royal Academy of Arts, London. > 234 > Charlie Godin Sir Jacob Epstein, “Primitive Mercenary in the Modern World” 235 > > Sir Jacob Epstein, “Primitive Mercenary in the Modern World” acob Epstein, born in Manhattan in 1880, is a figure for London at the age of twenty-four. too little known in the French-speaking world, even Having settled in the poor neighbourhood of St Pancras, Jtoday. The son of Polish Jewish émigrés, he spent Epstein, who had just completed his art training, launched his youth on Hester Street on the Lower East Side of New his career by sculpting a few children’s heads. His first York, a neighbourhood whose residents at the time were major public commission was for a group of sculptures immigrants from throughout the world. As a child, Epstein for the British Medical Association building on the Strand. had a passion for reading and for drawing, and he rapidly Here, he created his response to Greek statuary, especially acquired a taste for sketching the people around him and the Parthenon’s metopes, which he had seen at the British those he happened to run into. Gradually, his curiosity Museum and that represented the classical ideal. But he was impelled him to visit monuments and galleries, notably Paul also influenced by the aesthetic audacity of Indian art. The Durand-Ruel’s gallery on Fifth Avenue. Epstein, an admirer artist thus undertook a vast cycle on the Ages of Man (title of Manet, Pissarro and Renoir, enrolled at the prestigious Art pages), a project that lasted fourteen months. -

The Slade: Early Work, 1909–1913

The Slade: Early Work, 1909–1913 The Slade School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture was founded in 1871 by a series of endowments made by the collector and antiquary Felix Slade, and formed part of University College London. By 1893, when Fred Brown became Slade Professor, it had established a reputation for its liberal outlook and high standards of draughtsmanship. As his assistants Brown appointed the surgeon Henry Tonks to teach drawing, and Philip Wilson Steer to teach painting. Their students in the 1890s included Gwen and Augustus John, Spencer Gore, Ambrose McEvoy, William Orpen and Percy Wyndham Lewis. Tonks would later dub this era the Slade’s first ‘crisis of brilliance’. Students drawn to the School between 1908 and 1914 included the six young artists featured in this exhibition: Paul Nash, C.R.W. Nevinson, Stanley Spencer, Mark Gertler, Dora Carrington and David Bomberg. Though born in England, Bomberg and Gertler were the sons of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, and grew up in relative poverty in the East End of London. Their fees at the Slade were paid by a loan from a charitable organization, the Jewish Education Aid Society. Carrington, Nash, Nevinson and Spencer all came from middle class families, and grew up respectively in Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Hampstead and Berkshire. Their peers at the School included other such ambitious young artists as Adrian Allinson, John Currie, Ben Nicholson, William Roberts and Edward Wadsworth. Tonks called this flourish of talent and torment the School’s second and last ‘crisis of brilliance’. Most went on to become the leading British artists of the twentieth-century. -

Jacob Epstein's London

Jacob Epstein’s London The sculptor’s legacy 50 years after his death 5 Jacob Epstein (who died on 6 Field Marshal Smuts, August 19 1959) was one of the 1 Parliament Square, greatest British sculptors of Westminster (1956) the twentieth century. He was Like an ice skater, hands clasped also the most controversial. firmly behind his back, the former His sculptures have been South African prime minister Jan decapitated, castrated, covered in Christian Smuts cuts a thrusting paint and tarred and feathered. figure. Smuts was a controversial ‘He took the brickbats,’ said subject – soldier, statesman and Henry Moore, ‘and he scholar, he was seen as a ground- took them first.’ 2 4 breaking humanitarian for his role Graham Barker in establishing the League of scours London for Nations, but he advocated racial his finest works. segregation and opposed black enfranchisement. Nelson Mandela, 1 BMA, now arms aloft, now attracts more Zimbabwe House, attention in the opposite corner. Strand (1908) On the junction with 6 ‘Pietà’, Congress House, Agar Street you’ll see Great Russell Street, a macabre spectacle: Bloomsbury (1957) 18 mutilated naked Speak nicely to the receptionists at figures in niches Congress House and around Zimbabwe House. 5 3 they’ll let you sneak Epstein was a daring choice as into the café to marvel sculptor for the British Medical at Epstein’s ‘Pietà’ Association headquarters. His across the courtyard. ‘Ages of Man’ figures were more Stark and square, the than Edwardian London could towering mother bear. Here were statues that ‘no figure grows out of the careful father would wish his stone plinth, the figure daughter… to see’, warned the of her lifeless son Evening Standard. -

Read More About Henry Moore

Henry Moore MEDIUM Sculpture NATIONALITY British LIFE DATES 1898 - 1986 Moore, a draftsman and printmaker, is generally acknowledged as the most important British sculptor of the 20th century. The seventh child of a miner, he was brought up in the small industrial town of Castleford. Moore joined the army in 1917 and was sent to France. He was gassed in the Battle of Cambrai and returned to England to convalesce. In 1919 he began the two-year course at Leeds School of Art. There he read Roger Fry’s Vision and Design (London, 1920), which introduced him to his most important formative influences: non-Western sculpture, with its three-dimensional realization of form and use of direct carving. In 1921 Moore was awarded a scholarship to study sculpture at the Royal College of Art in London. Visits to the British Museum were far more influential on his early development than his academic course work. Drawings of sculptures in Moore’s early sketchbooks indicate that Palaeolithic fertility goddesses, Cycladic and early Greek art, Sumerian, Egyptian and Etruscan sculpture, African, Oceanic, Peruvian and Pre-Columbian sculpture particularly interested him. Like Constantin Brancusi, Amedeo Modigliani, Jacob Epstein and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Moore believed passionately in direct carving and in “truth to materials,” respecting the inherent character of stone or wood. Almost all of his works from the 1920s and 1930s were carved sculptures, initially inspired by Pre-Columbian stone carving. Moore made his first visit to Paris in 1923 and was overwhelmed by the work of Cézanne, which he saw in the private collection of Auguste Pellerin (1852-1929) in Neuilly. -

Contemporary Art Society Annual Report 1953-54

Contemporary Art Society Contemporary Art Society, Tate Gallery, Millbank, S.W.I Patron Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother Executive Committee Raymond Mortimer, Chairman Sir Colin Anderson, Hon. Treasurer E. C. Gregory, Hon. Secretary Edward Le Bas, R.A. Sir Philip Hendy W. A. Evill Eardley Knollys Hugo Pitman Howard Bliss Mrs. Cazalet Keir Loraine Conran Sir John Rothenstein, C.B.E. Eric Newton Peter Meyer Assistant Secretary Denis Mathews Hon. Assistant Secretary Pauline Vogelpoel Annual Report 19534 Contents The Chairman's Report Acquisitions, Loans and Presentations The Hon. Treasurer's Report Auditor's Accounts Future Occasions Bankers Orders and Deeds of Covenant 10 Oft sJT CD -a CD as r— ««? _s= CO CO "ecd CO CO CD eds tcS_ O CO as. ••w •+-» ed bT CD ss_ O SE -o o S ed cc es ed E i Gha e th y b h Speec This year the Society can boast of having been more active than privileged to visit the private collections of Captain Ernest ever before in its history. We have, alas, not received by donation Duveen, Mrs. Edward Hulton, Mrs. Oliver Parker and Mrs. Lucy or legacy any great coliection of pictures or a nice, fat sum of Wertheim. We have been guests also at a number of parties, for money. Sixty members have definitely abandoned us, and a good which we have to thank the Marlborough Fine Art Ltd., (who many others, you will be surprised to hear, have without resigning, have entertained us twice), the Redfern Gallery, Messrs. omitted to pay their subscription. -

Jacob Epstein – the Indian Connection by RUPERT RICHARD ARROWSMITH Christ Church, University of Oxford

Jacob Epstein – the Indian connection by RUPERT RICHARD ARROWSMITH Christ Church, University of Oxford SURVEYS OF MODERNIST British sculpture regularly begin with a description of the architectural carvings made by Jacob Epstein for the new British Medical Association building on the Strand in London during 1907 and 1908 (Fig.26). Despite this apparent consensus among art histor- ians, it is still far from clear exactly why the carvings should herald such a radical change in sculptural aesthetics and tech - niques, and what Epstein’s intentions were in creating them. Fortunately, a century after the sculptor began work on the project, new evidence has emerged that goes a long way towards clarifying both questions. The present article not only confirms the position of the BMA carvings at the roots of British Modernism, but also exposes their debt to a specific artistic tradition from outside Europe. Intercultural aesthetic exchange is persistently ignored in discussions of early Modernism, in particular, but Epstein’s trans-national leanings confirm it as an important factor even during the first decade of the twentieth century. Epstein’s sculptures for the BMA are regularly lumped together by critics into one series, when in fact they fall into two distinct groups. 1 Charles Holden, the architect of the new headquarters, pointed this out to a journalist for the British Medical Journal as early as 1907. While an initial group of reliefs was to ‘represent medicine and its allied sciences, chemistry, anatomy, hygiene, medical research and experi - 26. The British Medical Association Headquarters (429 Strand, Westminster), designed by Charles Holden as partner of Adams, Holden & Pearson.