'“Upon Your Entry Into the World”: Masculine Values and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter 298 AMDG F E B R U a R Y 2 0 0 9

stonyhurst association NEWSLETTER NEWSLETTER 298 AMDG FEBRU A R Y 2 0 0 9 1 stonyhurst association NEWSLETTER NEWSLETTER 298 AMDG FEBRUA RY 2009 lourdes 150th anniversary edition CONTENTS FROM THE CH A IR man F CHRist came TO TURN THE Pedro Arrupe arrived in Lourdes as a Diary of Events 4 world upside down, Berna dette, medical student but left to become a Congratulations 5 that stalwart by whom Lourdes Jesuit. His life was transformed, and Iis now known throughout the world, he challenged us also, as Jesuit alumni, Correspondence is another example of his amazing to transform our lives. To him, a Jesuit & Miscellany 6 aptitude to choose the right people to education that was not an education be vehicles of his grace. Bernadette for justice was deficient. By justice, Reunions & Convivia 8 was the antithesis of worldly power; Arrupe meant first a basic respect for small, frail, illiterate, living in all which forbids the use of others 1983 Reunion 9 absolute poverty in the Cachot (the as instruments for our own profit; Eagle Aid 10 town gaol). The transformational second, a firm resolve not to profit force of the messages that she passed passively from the active oppression Charities’ News 11 to us reflects the power of the gospel. of others and which refuses to be a Lourdes is an upside down place, silent beneficiary of injustice; third, a Lourdes 13 where the ‘malades’ are carried or decision to work with others towards Headmaster’s Report 21 pushed at the front of all the liturgies dismantling unjust social structures, and processions, where so called so as to set free those who are weak Committee Report 23 “broken humanity” is promoted to and marginalised. -

H. T. Weld Family History

HENRY THOMAS WELD FAMILY HISTORY Including the Research of Guy Sinclair in Great Britain Written by William Bauman C & O Canal Association Volunteer Revised SEPTEMBER 2016 1 2 PREFACE This family history was written starting with the Last Will and Testament of Henry Thomas Weld, then the disposition of his estate, then the Last Will and Testament of his wife, Harriet Emily Weld, and what could be found about the disposition of her estate. Then census data was found and, with the help of Guy Sinclair of Great Britain, the table of family statistics was built. From there newspapers and other sources were culled to fill in the life and time of this couple. They had no children and so this branch of the family tree stops with their deaths. There is a lot of information provided as attachments which the casual reader is not expected to read. It is included for completeness; many of the references are obscure and thus, rather than tax the family devotees to reconstruct them, I have included them here. Mr. & Mrs. Weld wintered in Baltimore and had a summer residence in Mount Savage; he had coal mining interests as well as a canal boat building yard to run. Presumably he commuted to Cumberland. The inventory of Mr. Weld's estate shows they lived comfortably. The General Index to Deeds, Etc., Allegany County, Md. lists 79 deeds, starting from 1844 through 1894, under the family name Weld. Most of the deeds were in Henry’s name, a few in Harriet’s name and the balance in both their names. -

The Rite of Sodomy

The Rite of Sodomy volume iii i Books by Randy Engel Sex Education—The Final Plague The McHugh Chronicles— Who Betrayed the Prolife Movement? ii The Rite of Sodomy Homosexuality and the Roman Catholic Church volume iii AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution Randy Engel NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Export, Pennsylvania iii Copyright © 2012 by Randy Engel All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, New Engel Publishing, Box 356, Export, PA 15632 Library of Congress Control Number 2010916845 Includes complete index ISBN 978-0-9778601-7-3 NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Box 356 Export, PA 15632 www.newengelpublishing.com iv Dedication To Monsignor Charles T. Moss 1930–2006 Beloved Pastor of St. Roch’s Parish Forever Our Lady’s Champion v vi INTRODUCTION Contents AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution ............................................. 507 X AmChurch—Posing a Historic Framework .................... 509 1 Bishop Carroll and the Roots of the American Church .... 509 2 The Rise of Traditionalism ................................. 516 3 The Americanist Revolution Quietly Simmers ............ 519 4 Americanism in the Age of Gibbons ........................ 525 5 Pope Leo XIII—The Iron Fist in the Velvet Glove ......... 529 6 Pope Saint Pius X Attacks Modernism ..................... 534 7 Modernism Not Dead— Just Resting ...................... 538 XI The Bishops’ Bureaucracy and the Homosexual Revolution ... 549 1 National Catholic War Council—A Crack in the Dam ...... 549 2 Transition From Warfare to Welfare ........................ 551 3 Vatican II and the Shaping of AmChurch ................ 561 4 The Politics of the New Progressivism .................... 563 5 The Homosexual Colonization of the NCCB/USCC ....... -

Male Anxiety Among Younger Sons of the English Landed Gentry, 1700-1900

The Historical Journal Male anxiety among younger sons of the English landed gentry, 1700-1900 Journal: The Historical Journal Manuscript ID HJ-2016-158.R2 Manuscript Type: Article Period: 1700-99, 1800-99 Thematic: General, Social Geographic: Britain Cambridge University Press Page 1 of 39 The Historical Journal Male Anxiety and Younger Sons of the Gentry MALE ANXIETY AMONG YOUNGER SONS OF THE ENGLISH LANDED GENTRY, 1700-1900 HENRY FRENCH & MARK ROTHERY* University of Exeter & University of Northampton Younger sons of the gentry occupied a precarious and unstable position in society. They were born into wealthy and privileged families yet, within the system of primogeniture, were required to make their own way in the world. As elite men their status rested on independence and patriarchal authority, attaining anything less could be deemed a failure. This article explores the way that these pressures on younger sons emerged, at a crucial point in the process of early adulthood, as anxiety on their part and on the part of their families. Using the correspondence of 11 English gentry families across this period we explore the emotion of anxiety in this context: the way that it revealed ‘anxious masculinities’; the way anxiety was traded within an emotional economy; the uses to which anxiety was put. We argue that anxiety was an important and formative emotion within the gentry community and that the expression of anxiety persisted among younger sons and their guardians across this period. We therefore argue for continuity in the anxieties experienced within this emotional community. On 23 February 1711 Thomas Huddlestone, a merchant’s apprentice in Livorno, Italy, penned a letter home to Cambridge, addressed to his mother but intended for the attention of both of his parents.1 In it he explained his predicament concerning his relationship with his employer, Mr. -

UNDER the BLACK HORSE FLAG ~Nnals of the Weld Family and Some of Its Branches

UNDER THE BLACK HORSE FLAG ~nnals of the Weld Family and Some of its Branches BY ISABEL ANDERSON, L1rr. D~ (Mrs. Larz Anderson) WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY Ut:bt l\ibet.sibe ~res~ Qtamlltibgt 1926 COPYRIGHT, 1926, BY ISABEL ANDERSON ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ilrf:Jt B.fbtrsibt ~rtss CAMBRIDGE • MASSACHUSETTS PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. , ..-L r ~ ...... ~ ·\?' :. _,./ ..- . ' . < ~ • U~DER THE BLACK HORSE FLAG Under the Black Horse Flag Preface THIS book is written for the f amity, and also, per haps, for those who love the sea, for my grand father's firm, the William Fletcher Weld Company, outlasted most of the merchant ship-owning houses in Boston, and after the Civil War it had the largest sailing fleet in America. The Black Horse Flag, which flew above his clippers, was a familiar sight to sailors, and many of his vessels were famous for their speed and general seaworthiness. The largest and swiftest of them all was the Great Admiral. At first I planned simply to collect and bind the logs of these clippers, but, finding that the greater portion of them would be of interest only to mari ners, I decided merely to use extracts. I have drawn as well upon family papers, which include both Weld and Anderson documents and my father's naval journals during the Civil War. These papers and logs opened up vistas of the Orient, the Barbary Coast, the Spanish Main, and pirates of the seven seas. When clippers no longer made white the ocean, the Black Horse Flag did not disappear, but flies to-day from the masthead of the yachts owned by different members of the Weld family. -

Impotence Trials and the Trans-Historical Right to Marital Privacy

BEHIND CLOSED DOORS: IMPOTENCE TRIALS AND THE TRANS-HISTORICAL RIGHT TO MARITAL PRIVACY * Stephanie B. Hoffman INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1725 I. SEPARATION BASED ON IMPOTENCE ................................................. 1728 A. Impotence as a Cause for Nullification ..................................... 1728 B. Procedure in Consistory Courts ................................................ 1730 C. Building a Case for Impotence .................................................. 1731 1. The Inquisitorial System and Evidence in Consistory Courts………. ....................................................................... 1731 2. The Wife’s Allegations ........................................................ 1732 D. Litigants ..................................................................................... 1735 II. POPULARIZING IMPOTENCE TRIALS ................................................... 1738 A. Publication ................................................................................ 1739 1. Edmund Curll and the Rise of Published Courtroom Drama.………. ....................................................................... 1740 2. Lady Elizabeth Weld: An Impotence Trial Case Study ....... 1743 3. Non-Book Publications ....................................................... 1745 B. Factors in Society ...................................................................... 1746 III. IMPOTENCE TRIALS: THE MARITAL PRIVACY COUNTEREXAMPLE ... 1749 CONCLUSION -

Dr. a NT) ER SO N%

% yohofhaH make fucb Discoveries as are abov*-nt entioftd,'t ab'j^he i# Day jpf this Termj requiring him -to appear to aVid * to be paid upon the Convidion of the faid Offenders, antwer the fame; but the Defendant hath not So done, as by rhe Six Clerks Certificate appeared ; and that upon Inquiry t0r hrh oni or niore of them, bj" Jamei Fel(, of Ten at the. laid Defendant's usual Place of Abode, he ia not, to be tburcbfrsst, London, Hpbezd&Jber, found so as to served with such Procesi, and that he is -gone out James Fell, \ of riœ Realm, and doth abscond to avoid being served therewith, as by Affidavit ajso appeared ; and that the said Certificates and Affidavits being now read, this Court doth order, thac the said Mine-Office, Oftober 30, 1745. Defendant do appear on or before the lost Day of thia Term, This is to give Nofce, that a Qeneral Court of tbe Wl HEREAS a Letter has been transmitted to thc Earl of Governor and Company of the Mine Adventurers of •VV Shastsbury, Lord Lieutenant of the County "of Dorset, sjid to be found on the Highway near Poole, dated Sept* 2Z, England, -witlbt held at'this Office; on Thursday the 1745^ and figned J. W. with the Words £fqj Weld ist iqjb Day of November nixi* at Twelve at Noont for Purbeck superscribed, insinuating some Promises of Assistance hi tbe Elt&ion of ar Governor, Deputy Governor, and \ Cafe of a Descent in the West! I Edward Weld do tal^e Twelve X>ireclors for the Itear enffiingx pursuant to the th's publipk Opportunity to testify my Innocence, and my .De Charter and Att os parliaments concerning (he Affairs sire to bring the Author or Authors of so base, scandalous ani malicious a Libel, to condign Punishment; and in ordeV thereto, of tbe said Company* And that the-Tr an ser Books do hereby promise a Reward of F< rty Pounds to arty Person who will j?e Jhtit from a> d after 'Thursday the Jib, anU sliall discover the Author or Authors of the said Letter J tb Be optntd again on Thursday the Zist Day os the said paid immediately on his or their Conviction, by me, month of November next* Lulworth Castle* Oct. -

Salters (Deer Leaps) in Historical Deer Parks: Leagram Park in 1608

Salters (deer-leaps) in Leagram deer-park, 1608 SaltersSalters (deer (Deer--leaps)Leaps) in in historicalHistorical deerDeer park-Park boundariesBoundaries: A case studyA C aseemploying Study Using a 1 a608 1608 dispute Dispute map Map ofof Leagram Park in Bowland Leagram park in Bowland, Lancashire Image goes here Crop to 19cm wide by 9.36cm deep Click format picture then under layout click advanced and place 1cm to the right of page and 5.65cm below page. DELETE THIS BOX Dr Graham Cooper September 2014 Dr Graham Cooper Salters (deer-leaps) in Leagram deer-park, 1608 Salters (deer-leaps) in Leagram deer-park, 1608 Salters (Deer-Leaps) in Historical Deer-Park Boundaries: A Case Study Using a 1608 Dispute Map of Leagram Park in Bowland Ver. 1 Dr Graham Cooper [email protected] Salters (deer-leaps) in Leagram deer-park, 1608 Contents Summary ....................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Foreword ...................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Report structure .................................................................................................................................................... 9 Part 1: Deer-parks, -

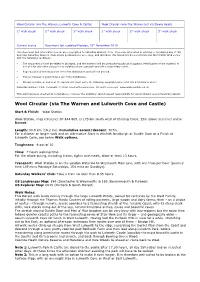

Wool Circular (Via the Warren and Lulworth Cove and Castle)

Wool Circular (via The Warren, Lulworth Cove & Castle) Wool Circular (w/o The Warren but via Swyre Head) 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check Current status Document last updated Monday, 25th November 2019 This document and information herein are copyrighted to Saturday Walkers’ Club. If you are interested in printing or displaying any of this material, Saturday Walkers’ Club grants permission to use, copy, and distribute this document delivered from this World Wide Web server with the following conditions: • The document will not be edited or abridged, and the material will be produced exactly as it appears. Modification of the material or use of it for any other purpose is a violation of our copyright and other proprietary rights. • Reproduction of this document is for free distribution and will not be sold. • This permission is granted for a one-time distribution. • All copies, links, or pages of the documents must carry the following copyright notice and this permission notice: Saturday Walkers’ Club, Copyright © 2019, used with permission. All rights reserved. www.walkingclub.org.uk This walk has been checked as noted above, however the publisher cannot accept responsibility for any problems encountered by readers. Wool Circular (via The Warren and Lulworth Cove and Castle) Start & Finish: Wool Station Wool Station, map reference SY 844 869, is 173 km south west of Charing Cross, 15m above sea level and in Dorset. Length: 30.9 km (19.2 mi). Cumulative ascent/descent: 707m. For a shorter or longer walk and an Alternative Start in Winfrith Newburgh or Durdle Door or a Finish at Lulworth Cove, see below Walk options. -

The Ceremony

The Ceremony. LULWORTH CASTLE THE CEREMONY PAGE 1 THE CEREMONY PAGE 2 Photo: David Wheeler Photography Wheeler David Photo: Photography Wheeler David Photo: A FAIRYTALE CASTLE BY THE SEA Built to entertain royalty, this stunning 17th century castle is set at the heart of the family-owned Lulworth Estate in extensive rolling parkland, with sea views, a beautiful church and a private chapel in the grounds. Through the centuries, Lulworth Castle has played host to countless guests - including seven monarchs. Today, it offers a breathtakingly beautiful backdrop for your wedding in a truly iconic setting on the Jurassic Coast. THE CEREMONY PAGE 1 THE CEREMONY PAGE 2 “Grow Old With Me. The Best Is Yet To Be.” Robert Browning Photo: David Wheeler Photography Photo: Emma Hurley Photography Exclusively Yours Photo: David Wheeler Photography Wheeler David Photo: Available for exclusive hire, the magical Lulworth Castle is a blank and flexible canvas waiting for you to create your perfect day. Choose a civil ceremony in the castle, or take your vows in its ancient church or historic private chapel. Then eat, drink and celebrate the happiest day of your life in this magical and timeless place. THE CEREMONY PAGE 3 “Once Upon A Time, I Became Photo: David Wheeler Photography Wheeler David Photo: Yours And You Became Mine.” Anon Your Ceremony Lulworth Castle is licensed for civil ceremonies and symbolic blessings, which take place at the heart of this historic building. The 15th century Anglican church and the 17th century private Catholic chapel are also just a short walk from the castle. -

British Aristocratic Women and Their Role in Politics, 1760-1860

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 11-1-1994 British Aristocratic Women and Their Role in Politics, 1760-1860 Nancy Ann Henderson Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Henderson, Nancy Ann, "British Aristocratic Women and Their Role in Politics, 1760-1860" (1994). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4799. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6682 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Nancy Ann Henderson for the Master of Arts in History were presented November 1, 1994, and accepted by the thesis committee and the department. COMMITTEE APPROVALS: Ann/~ikel, Chair David Joe_,~on susan Karant- unn .. r Christine Thompson Representative of the Office of Graduate Studies DEPARTMENT APPROVAL: David John,s6nJ Chair Departmen~ off History ******************************************************** ACCEPTED FOR PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY BY THE LIBRARY b on/Z..&&e~42¢.- /9'9<f ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Nancy Ann Henderson for the Master of Arts in History presented November, 1, 1994. Title: British Aristocratic Women and Their Role in Politics, 1760-1860. British aristocratic women exerted political influence and power during the century beginning with the accession of George III. They expressed their political power through the four roles of social patron, patronage distributor, political advisor, and political patron/electioneer. -

Pedigrees of the County Families of Yorkshire

Gc ,1- 942.7401 ^' '— F81p v,2 1242351 GENEALOGY COLLECTION 3 1833 01941 3043 PEDIGREES YORKSHIRE FAMILIES. PEDIGREES THE COUNTY FAMILIES YORKSHIRE JOSEPH FOSTER AND AUTIIRNTICATRD BY THE MEMBERS Of EACH FAMIL\ VOL. II.—WEST RIDING LONDON: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED FOR THE COMPILER BY W. WILFRED HEAD, P L O U O H COURT, FETTER LANE, E.G. 1874. 1242351 LIST OF PEDIGREES IN VOL. II. small type refer to fa Hies introduced into the Pedigrees, the second name being the Pedis the former appears: 'hus, Marriott will be found on reference to the Maude Pedigree. MARKHAM, of Cufforth Hall, forjierlv Becca. Nooth—Vavasour. Marriott—Maude. Norcliffe- Dalton. Marshall, of Ne\vton Kyme and Laughton— Hatfeild. North—Rockley. Martin—Edmunds. NORTON (Baron Gr.antley), of Gk.vntlev i MAUDE, OF Alverthorpe, Wakefield, &c. GATES, OF Nether Denby, and Raw'.marsh. Maude—Tempest GATES, OF Meanwoodside. Mauleverer—Laughton. Ogden—Maude. Maxwell—Midelton. Oliver—Gascoigne. Maynard—Sherd, Westby. Ormston—Aldam Melvill— Lister. Owen—Radclyffe, Rodgers. Metcalfe—More. Palmer—Roundell, Meynell—Ingram. PARKER, LATE OF WoodjWiorpe, MICKLETHWAITE, OF INGBIRCHWORTH, .\rdslev Parker—Lister, Walker. HOUSE, &C. (jft'Vol. 3.) St. Paul—Bosvile. MIDDELTON, of Stockeld a.\d Miiuielto.N' Lodge. Pease—Aldam. Milbanke—Wentworth, Nos. i and 2. Pedwardyn— Savile of Thornhill. MILNER, of Burton Grange. Pemberton—Stapleton. MILNER, of Pudsev, now of Nun Arpleto.n. Perceval—Westby. MlLNESj of Wakefield and (Baron Houghton) Percy—Foljambe, Heber. Fryston. Pickford-Radcliffe. Montagu—Wortley. Pickford, of Macclesfield—Radclyffe. Moore, of Frampton—More, of Barnborough. Pigot—Wood, of Hickleton. Moore—Foljambe. Pigott— Fairfax Moorsome —Maude. PILKINGTON, of Chevet Park, \-c.