Salters (Deer Leaps) in Historical Deer Parks: Leagram Park in 1608

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feral Wild Boar: Species Review.' Quarterly Journal of Forestry, 110 (3): 195-203

Malins, M. (2016) 'Feral wild boar: species review.' Quarterly Journal of Forestry, 110 (3): 195-203. Official website URL: http://www.rfs.org.uk/about/publications/quarterly-journal-of-forestry/ ResearchSPAce http://researchspace.bathspa.ac.uk/ This version is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite using the reference above. Your access and use of this document is based on your acceptance of the ResearchSPAce Metadata and Data Policies, as well as applicable law:- https://researchspace.bathspa.ac.uk/policies.html Unless you accept the terms of these Policies in full, you do not have permission to download this document. This cover sheet may not be removed from the document. Please scroll down to view the document. 160701 Jul 2016 QJF_Layout 1 27/06/2016 11:34 Page 195 Features Feral Wild Boar Species review Mark Malins looks at the impact and implications of the increasing population of wild boar at loose in the countryside. ild boar (Sus scrofa) are regarded as an Forests in Surrey, but meeting with local opposition, were indigenous species in the United Kingdom with soon destroyed. Wtheir place in the native guild defined as having Key factors in the demise of wild boar were considered to been present at the end of the last Ice Age. Pigs as a species be physical removal through hunting and direct competition group have a long history of association with man, both as from domestic stock, such as in the Dean where right of wild hunted quarry but also much as domesticated animals with links traced back to migrating Mesolithic hunter-gatherer tribes in Germany 6,000-8,000 B.P. -

Hamish Graham

14 French History and Civilization “Seeking Information on Who was Responsible”: Policing the Woodlands of Old Regime France Hamish Graham In a sense Pierre Robert was simply unlucky. Robert was a forest guard from Saint-Macaire, a small town on the right bank of the Garonne about twelve leagues (or nearly fifty kilometers) upstream from the regional capital of Bordeaux. In 1780 he was convicted of corruption and dismissed from the royal forest service, the Eaux et Forêts. According to lengthy testimonies compiled by his superiors, Robert had identified breaches by local landowners of the regulations about woodland exploitation set down in the 1669 Ordonnance des Eaux et Forêts. He then demanded payment directly from the offenders. The forestry officials took a dim view of these charges, and the full force of the law was brought to bear: Robert’s case went as far as the “sovereign court” of the Parlement in Bordeaux.1 Michel Marchier was also an eighteenth-century forest guard in south-western France whose actions could be considered corrupt: like Robert, Marchier was accused of soliciting a bribe from a known forest offender. Unlike Robert, however, Marchier was not subjected to judicial proceedings, and he was certainly not dismissed. His case was not even reported to the regional headquarters of the Eaux et Forêts in Bordeaux. Instead Marchier’s punishment was extra-judicial: he was publicly denounced in a local market-place, and then beaten up by his target’s son.2 There are several possible ways we could explain the different ways in which these two matters were handled, perhaps by focusing on issues of individual personality or the seriousness of the men’s offenses. -

Draft Order Modified.Pdf

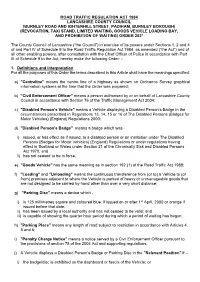

ROAD TRAFFIC REGULATION ACT 1984 LANCASHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL (BURNLEY ROAD AND IGHTENHILL STREET, PADIHAM, BURNLEY BOROUGH) (REVOCATION, TAXI STAND, LIMITED WAITING, GOODS VEHICLE LOADING BAY, AND PROHIBITION OF WAITING) ORDER 202* The County Council of Lancashire (“the Council”) in exercise of its powers under Sections 1, 2 and 4 of and Part IV of Schedule 9 to the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984, as amended (“the Act”) and of all other enabling powers, after consultation with the Chief Officer of Police in accordance with Part III of Schedule 9 to the Act, hereby make the following Order: - 1. Definitions and Interpretation For all the purposes of this Order the terms described in this Article shall have the meanings specified: a) "Centreline" means the centre line of a highway as shown on Ordnance Survey graphical information systems at the time that the Order was prepared; b) "Civil Enforcement Officer" means a person authorised by or on behalf of Lancashire County Council in accordance with Section 76 of the Traffic Management Act 2004; c) "Disabled Person’s Vehicle" means a Vehicle displaying a Disabled Person’s Badge in the circumstances prescribed in Regulations 13, 14, 15 or 16 of The Disabled Persons (Badges for Motor Vehicles) (England) Regulations 2000; d) "Disabled Person’s Badge" means a badge which was - i) issued, or has effect as if issued, to a disabled person or an institution under The Disabled Persons (Badges for Motor Vehicles) (England) Regulations or under regulations having effect in Scotland or Wales under Section 21 of the Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act 1970; and ii) has not ceased to be in force. -

Newsletter 298 AMDG F E B R U a R Y 2 0 0 9

stonyhurst association NEWSLETTER NEWSLETTER 298 AMDG FEBRU A R Y 2 0 0 9 1 stonyhurst association NEWSLETTER NEWSLETTER 298 AMDG FEBRUA RY 2009 lourdes 150th anniversary edition CONTENTS FROM THE CH A IR man F CHRist came TO TURN THE Pedro Arrupe arrived in Lourdes as a Diary of Events 4 world upside down, Berna dette, medical student but left to become a Congratulations 5 that stalwart by whom Lourdes Jesuit. His life was transformed, and Iis now known throughout the world, he challenged us also, as Jesuit alumni, Correspondence is another example of his amazing to transform our lives. To him, a Jesuit & Miscellany 6 aptitude to choose the right people to education that was not an education be vehicles of his grace. Bernadette for justice was deficient. By justice, Reunions & Convivia 8 was the antithesis of worldly power; Arrupe meant first a basic respect for small, frail, illiterate, living in all which forbids the use of others 1983 Reunion 9 absolute poverty in the Cachot (the as instruments for our own profit; Eagle Aid 10 town gaol). The transformational second, a firm resolve not to profit force of the messages that she passed passively from the active oppression Charities’ News 11 to us reflects the power of the gospel. of others and which refuses to be a Lourdes is an upside down place, silent beneficiary of injustice; third, a Lourdes 13 where the ‘malades’ are carried or decision to work with others towards Headmaster’s Report 21 pushed at the front of all the liturgies dismantling unjust social structures, and processions, where so called so as to set free those who are weak Committee Report 23 “broken humanity” is promoted to and marginalised. -

Histories of Value Following Deer Populations Through the English Landscape from 1800 to the Present Day

Holly Marriott Webb Histories of Value Following Deer Populations Through the English Landscape from 1800 to the Present Day Master’s thesis in Global Environmental History 1 Abstract Marriott Webb, H. 2019. Histories of Value: Following Deer Populations Through the English Landscape from 1800 to the Present Day. Uppsala, Department of Archaeology and Ancient His- tory. Imagining the English landscape as an assemblage entangling deer and people throughout history, this thesis explores how changes in deer population connect to the ways deer have been valued from 1800 to the present day. Its methods are mixed, its sources are conversations – human voices in the ongoing historical negotiations of the multispecies body politic, the moot of people, animals, plants and things which shapes and orders the landscape assemblage. These conversations include interviews with people whose lives revolve around deer, correspondence with the organisations that hold sway over deer lives, analysis of modern media discourse around deer issues and exchanges with the history books. It finds that a non-linear increase in deer population over the time period has been accompanied by multiple changes in the way deer are valued as part of the English landscape. Ending with a reflection on how this history of value fits in to wider debates about the proper representation of animals, the nature of non-human agency, and trajectories of the Anthropocene, this thesis seeks to open up new ways of exploring questions about human- animal relationships in environmental history. Keywords: Assemblages, Deer, Deer population, England, Hunting, Landscape, Making killable, Moots, Multispecies, Nativist paradigm, Olwig, Pests, Place, Trash Animals, Tsing, United Kingdom, Wildlife management. -

1580-Cannock Chase Web:6521-Cornwall 8/4/15 10:24 Page 1 a Guide for Parents and Carers of Children Aged Birth-5 Years

1580-Cannock Chase web:6521-Cornwall 8/4/15 10:24 Page 1 A guide for parents and carers of children aged birth-5 years Breastfeeding Immunisations Oral health Smoking Worried, need Confused, unsure or Need advice about If you smoke - now is support and advice? need advice? teething, oral health the time to quit. Common or registering? childhood Speak to your Speak to your Speak to your Health Visitor or Health Visitor or Health Visitor or contact your local Practice Nurse Dentist illnesses & Call 0800 022 4332 Breastfeeding Support or visit Team www.smokefree.nhs.uk well-being There are many everyday illnesses or health concerns which parents and carers need advice and information on. This handbook has been produced by NHS Cannock Chase Clinical Commissioning Group. www.cannockchaseccg.nhs.uk 01622 752160 www.sensecds.com Sense Interactive Ltd, Maidstone. © 2015 All Rights Reserved. Tel: 1580-Cannock Chase web:6521-Cornwall 8/4/15 10:24 Page 3 Welcome Contents This book has been put together by NHS Cannock Chase Clinical Who can help? Allergies 34 Commissioning Group with local Health Visitors, GPs and other healthcare A guide to services 4 Upset tummy 36 professionals. Know the basics 6 Constipation 38 Every parent or carer wants to know what to do when a child is ill - use this The first months Earache and tonsillitis 40 handbook to learn how to care for your child at home, when to call your GP and Crying and colic 8 Chickenpox and measles 42 when to contact the emergency services. Most issues your child will experience are part of growing up and are often helped by talking to your Midwife, Health Visitor Being sick 10 Urticaria or hives 44 or local Pharmacist. -

Lancashire Historic Town Survey Programme

LANCASHIRE HISTORIC TOWN SURVEY PROGRAMME BURNLEY HISTORIC TOWN ASSESSMENT REPORT MAY 2005 Lancashire County Council and Egerton Lea Consultancy with the support of English Heritage and Burnley Borough Council Lancashire Historic Town Survey Burnley The Lancashire Historic Town Survey Programme was carried out between 2000 and 2006 by Lancashire County Council and Egerton Lea Consultancy with the support of English Heritage. This document has been prepared by Lesley Mitchell and Suzanne Hartley of the Lancashire County Archaeology Service, and is based on an original report written by Richard Newman and Caron Newman, who undertook the documentary research and field study. The illustrations were prepared and processed by Caron Newman, Lesley Mitchell, Suzanne Hartley, Nik Bruce and Peter Iles. Copyright © Lancashire County Council 2005 Contact: Lancashire County Archaeology Service Environment Directorate Lancashire County Council Guild House Cross Street Preston PR1 8RD Mapping in this volume is based upon the Ordnance Survey mapping with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Lancashire County Council Licence No. 100023320 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Lancashire County Council would like to acknowledge the advice and assistance provided by Graham Fairclough, Jennie Stopford, Andrew Davison, Roger Thomas, Judith Nelson and Darren Ratcliffe at English Heritage, Paul Mason, John Trippier, and all the staff at Lancashire County Council, in particular Nik Bruce, Jenny Hayward, Jo Clark, Peter Iles, Peter McCrone and Lynda Sutton. Egerton Lea Consultancy Ltd wishes to thank the staff of the Lancashire Record Office, particularly Sue Goodwin, for all their assistance during the course of this study. -

The Old School, Park Lane, Richmond, London Borough of Richmond

T H A M E S V A L L E Y AARCHAEOLOGICALRCHAEOLOGICAL S E R V I C E S The Old School, Park Lane, Richmond, London Borough of Richmond Desk-based Heritage Assessment by Tim Dawson Site Code PLR12/80 (TQ 1793 7520) The Old School, Park Lane, Richmond, London Borough of Richmond Desk-based Heritage Assessment for Renworth Homes (Southern) Ltd In support of a detailed planning application and Conservation Area Consent application for the erection of three new townhouses, with car parking and conversion of existing school building for six residential units with car parking by Tim Dawson Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd Site Code PLR 12/80 AUGUST 2012 Summary Site name: The Old School, Park Lane, Richmond, London Borough of Richmond Grid reference: TQ 17925 75200 Site activity: Desk-based heritage assessment Project manager: Steve Ford Site supervisor: Tim Dawson Site code: PLR 12/80 Area of site: c.0.12ha Summary of results: The Old School lies in an area of high archaeological potential with finds and features dating from the Palaeolithic period onwards being discovered nearby. Richmond itself was an important centre with its royal palace dating from the medieval period. While construction of the school in 1870 is likely to have disturbed at least the most shallow archaeological deposits, the area under the playground is less likely to have been truncated allowing for the preservation of archaeologically sensitive layers. It is anticipated that it will be necessary to provide further information about the archaeological potential of the site from field observations, in order to draw up a scheme to mitigate the impact of the proposed residential development on any below-ground archaeological deposits if necessary. -

Quaternary Science Reviews 42 (2012) 74E84

Author's personal copy Quaternary Science Reviews 42 (2012) 74e84 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Quaternary Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quascirev Phylogeographic, ancient DNA, fossil and morphometric analyses reveal ancient and modern introductions of a large mammal: the complex case of red deer (Cervus elaphus) in Ireland Ruth F. Carden a,*, Allan D. McDevitt b, Frank E. Zachos c, Peter C. Woodman d, Peter O’Toole e, Hugh Rose f, Nigel T. Monaghan a, Michael G. Campana g, Daniel G. Bradley h, Ceiridwen J. Edwards h,i a Natural History Division, National Museum of Ireland (NMINH), Merrion Street, Dublin 2, Ireland b School of Biology and Environmental Science, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland c Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Vienna, Austria d 6 Brighton Villas, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland e National Parks and Wildlife Service, Killarney National Park, County Kerry, Ireland f Trian House, Comrie, Perthshire PH6 2HZ, Scotland, UK g Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, 11 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge 02138, USA h Molecular Population Genetics Laboratory, Smurfit Institute, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin 2, Ireland i Research Laboratory for Archaeology, University of Oxford, Dyson Perrins Building, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3QY, UK article info abstract Article history: The problem of how and when the island of Ireland attained its contemporary fauna has remained a key Received 29 November 2011 question in understanding Quaternary faunal assemblages. We assessed the complex history and origins Received in revised form of the red deer (Cervus elaphus) in Ireland using a multi-disciplinary approach. Mitochondrial sequences of 20 February 2012 contemporary and ancient red deer (dating from c 30,000 to 1700 cal. -

The Earlier Parks Charles I's New Park

The Creation of Richmond Park by The Monarchy and early years © he Richmond Park of today is the fifth royal park associated with belonging to the Crown (including of course had rights in Petersham Lodge (at “New Park” at the presence of the royal family in Richmond (or Shene as it used the old New Park of Shene), but also the Commons. In 1632 he the foot of what is now Petersham in 1708, to be called). buying an extra 33 acres from the local had a surveyor, Nicholas Star and Garter Hill), the engraved by J. Kip for Britannia Illustrata T inhabitants, he created Park no 4 – Lane, prepare a map of former Petersham manor from a drawing by The Earlier Parks today the “Old Deer Park” and much the lands he was thinking house. Carlile’s wife Joan Lawrence Knyff. “Henry VIII’s Mound” At the time of the Domesday survey (1085) Shene was part of the former of the southern part of Kew Gardens. to enclose, showing their was a talented painter, can be seen on the left Anglo-Saxon royal township of Kingston. King Henry I in the early The park was completed by 1606, with ownership. The map who produced a view of a and Hatch Court, the forerunner of Sudbrook twelfth century separated Shene and Kew to form a separate “manor of a hunting lodge shows that the King hunting party in the new James I of England and Park, at the top right Shene”, which he granted to a Norman supporter. The manor house was built in the centre of VI of Scotland, David had no claim to at least Richmond Park. -

Nine Community Radio Licence Awards: October 2017

Community radio Nine community radio licence awards: October 2017 Statement: Publication Date: 8 November 2017 About this document This document announces the award of nine community radio licences. The licences are for stations serving communities in Cannock and Rugeley (Staffordshire), Cinderford (Forest of Dean), each of Keynsham, Yeovil, and Minehead (all in Somerset), each of Swanage and Dorchester (both in Dorset), Newquay (Cornwall) and the Rhondda in south Wales. Contents Section 1. Licence awards 1 2. Statutory requirements relating to community radio licensing 5 Nine community radio licence awards: October 2017 1. Licence awards 1.1 During October 2017, Ofcom made decisions to award nine community radio licences. The licences are for stations serving communities in Cannock and Rugeley (Staffordshire), Cinderford (Forest of Dean), Keynsham, Yeovil, Minehead (all in Somerset), Swanage, Dorchester (both in Dorset), Newquay (Cornwall) and the Rhondda in south Wales. 1.2 All community radio services must satisfy certain 'characteristics of service' which are specified in legislation1 – Ofcom was satisfied that each applicant awarded a licence met these 'characteristics of service'. In addition, each application was considered having regard to statutory criteria2, the details of which are described below. This statement sets out the key considerations in relation to these criteria which formed the basis of Ofcom's decisions to award the licences. Where applicable, the relevant statutory reference (indicated by the sub-paragraph number) -

The Bishop of Winchester's Deer Parks in Hampshire, 1200-1400

Proc. Hampsk. Field Club Archaeol. Soc. 44, 1988, 67-86 THE BISHOP OF WINCHESTER'S DEER PARKS IN HAMPSHIRE, 1200-1400 By EDWARD ROBERTS ABSTRACT he had the right to hunt deer. Whereas parks were relatively small and enclosed by a park The medieval bishops of Winchester held the richest see in pale, chases were large, unfenced hunting England which, by the thirteenth century, comprised over fifty grounds which were typically the preserve of manors and boroughs scattered across six southern counties lay magnates or great ecclesiastics. In Hamp- (Swift 1930, ix,126; Moorman 1945, 169; Titow 1972, shire the bishop held chases at Hambledon, 38). The abundant income from his possessions allowed the Bishop's Waltham, Highclere and Crondall bishop to live on an aristocratic scale, enjoying luxuries (Cantor 1982, 56; Shore 1908-11, 261-7; appropriate to the highest nobility. Notable among these Deedes 1924, 717; Thompson 1975, 26). He luxuries were the bishop's deer parks, providing venison for also enjoyed the right of free warren, which great episcopal feasts and sport for royal and noble huntsmen. usually entitled a lord or his servants to hunt More deer parks belonged to Winchester than to any other see in the country. Indeed, only the Duchy of Lancaster and the small game over an entire manor, but it is clear Crown held more (Cantor et al 1979, 78). that the bishop's men were accustomed to The development and management of these parks were hunt deer in his free warrens. For example, recorded in the bishopric pipe rolls of which 150 survive from between 1246 and 1248 they hunted red deer the period between 1208-9 and 1399-1400 (Beveridge in the warrens of Marwell and Bishop's Sutton 1929).