Improving International Cooperation To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vancouver, Bc / January 27 – 29, 2017

VANCOUVER, BC / JANUARY 27 – 29, 2017 VANCOUVER CONVENTION CENTRE / GENERAL ADMISSION FREE MISSIONSFESTVANCOUVER.CA Proclaiming Jesus Christ as Life! • Bible School • Conferences • Outdoor Education • Private Retreats • Personal Getaways VISIT US! Booths R7 & S7! CAPERNWRAY . CA TABLE OF Missions Fest Program Magazine is the official publication of Missions Festival CONTENTS (Missions Fest) Society. Missions Fest Program Magazine is published by Missions Fest Vancouver. PROGRAMMING Weekend at a Glance 4 Missions Fest & Design and Missions Theme: Justice and the Gospel 5 Fest are trademarks owned by the Missions Fest International Association Children’s Programs 13 and used under licence by Missions New this Year 14 Festival (Missions Fest) Society. Arts Café 14 Prayer 20 Managing Editor John Hall Saturday Night @ MFV; Youth Rally, Club 67 22 Assistant Editor Sandra Crawford Copy Editor Angela Lee Atesto 22 Agency Relations Emily Aspinall Mini Conference 26 Church Relations Claudia Rossetto General Sessions (Themes & Narrative) 28 Layout and Design Peter Pasivirta Fit Faith Challenge 28 Cover Colors and Shapes Worship Team: Worship Central & Performing Artists 29 Film Festival 30 Missions Fest gratefully accepts Seminar Series 33 donations online and through cash, Seminars (By Time - By Presenter - By Theme) 34 cheques or credit card. EDITORIAL Missions Fest is a certifi ed member of the Canadian Welcome from the Director John Hall 9 Council of Christian Charities. Welcome from the Board Chair Calvin Weber 9 Plenary Speakers’ Biographies -

The Sexual Exploitation of Children in Travel and Tourism Creating A

ECPAT International Creating a United Front against the Sexual Exploitation of Children in Travel and Tourism The following papers in this journal were presented at the XVIIth ISPCAN International Congress on Child Abuse and Neglect, held from 7-10 September 2008, in Hong Kong: Understanding the linkages between CST and other forms of CSEC in East Asia and the Pacific. Extraterritorial laws: why they are not really working and how they can be strengthened. Lessons learned and good practices on working with the private sector to combat CST and trafficking for sexual exploitation. June 2009 Copyright © ECPAT International ECPAT International is a global network of organisations and individuals working together to eliminate child prostitution, child pornography and the trafficking of children for sexual purposes. It seeks to encourage the world community to ensure that children everywhere enjoy their fundamental rights free and secure from all forms of commercial sexual exploitation. Extracts from this publication may be freely reproduced provided that due acknowledgment is given to ECPAT International. ECPAT International 328/1 Phayathai Road Ratchathewi Bangkok 10400 THAILAND Tel: +662 215 3388, +662 611 0972 Fax: +662 215 8272 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ecpat.net 1 Table of Contents Acronyms 3 Preface 4 Extraterritorial laws: why they are not really working and how they can be strengthened 6 2 Understanding the linkages between CST and other forms of CSEC in East Asia and the Pacific 23 Lessons learned and good practices on working -

Code of Conduct to Protect Children from Sexual Exploitation in Travel and Tourism

Code of Conduct for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation in Travel and Tourism International Newsletter No. 28 April - June 2011 Contributors: 1. The Tourism Child-Protection Code of Conduct, Secretariat, Dr. Camelia Tepelus Americas 2. Belize Tourism Board, Raymond Mossiah 3. IBCR Canada, Nadja Pollaert 4. Beyond Borders Canada, Deborah Zanke 5. ECPAT USA, Carol Smolenski, Michelle Guelbart Europe 6. ECPAT Netherlands, Celine Verheijen 7. IDH Dutch Sustainable Trade Initiative, Marieke Abcouwer Africa 8. Fair Trade in Tourism South Africa, Julia Kandzia CNN Jim Clancy interviewing ECPAT USA Carol Smolenski on 9. Sun‘n‘Sand Kenya, Shahinoor Visram child protection in tourism and the Code implementation. 10. AllAfrica.com - Kenya Video available at http://edition.cnn.com/video/#/video/world/2011/05/19/cf Asia p.tourism.code.smolenski.cnn 11. ECPAT International, Patchareeboon Sakulpitakphon 12. ECPAT New Zealand, Alan Bell Foreseen Welcome to 27 new Code members so far in 2011! Colombia (Cartagena de Indias) Hotel El Pueblito; Hotel LM; Hotel Cartagena Plaza; Playas del Caribe s.a; Hotel Casa Pestagua; Hotel Delirio; Casa Quero; Quadrifolio; Hotel Dorado y San Felipe; Hotel Puertas de Cartagena y Hotel Santa Cruz USA Delta Air Lines and Hilton Hotels (Washington DC and Seattle) Germany ITB Messe and Accor Germany South Africa Access Guest Lodge; Andulela ExperienceCactusberry Lodge; Calabash Tours; CityLodge Hotel Ltd; Europcar South Africa; Fairfield Tours PTY Ikhayalam Lodge & Tours; The Safari Lodge; Spier Resort Management -

FCPO-Canada National Conference June 25 – 28Th 2015, Burlington, ON

January, 2015 Ph: (604) 200-FCPO (3276) Email: [email protected] From the Editor’s Desk - IMPORTANT – You need to register online It has been some years since we last updated our membership list. So, notwithstanding the fact that you may have taken out a membership with FCPO-Canada many years ago, or even just recently, we are asking that you go online and register again. There is no membership fee. There are two important reasons we need you to do this. First, we want to ensure that we have Merv Tippe an updated list of members with their most current information. Second, one of the FCPO – Canada’s best communication tools has always been the PeaceMaker and since our inception, we have regularly mailed hard copies of the PeaceMaker to our subscribers. We are now in an era where many folks prefer receiving newsletters electronically. Thanks to an upgrade to our website, we are moving to “real time” delivery of the PeaceMaker to one’s email or mobile device. This electronic format will include enhanced features such as actionable links to other references and the ability to contact us through a variety of means with just one click. The electronic format will allow you to easily forward the PeaceMaker to friends and others who may be interested in a particular issue. In addition, the electronic PeaceMaker is environmentally friendly and a cost effective distribution method for us. We realize that perhaps not all of our members use email and perhaps there are some who haven’t moved to the use of computers. -

Brief Submitted to ETHI

To the Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics Re. Protection of Privacy and Reputation on Platforms such as Pornhub February 22, 2021 We applaud the Canadian Government for working to hold MindGeek accountable for facilitating and profiting from sexual abuse and exploitation.1 MindGeek, which owns Pornhub and at least 160 other hardcore pornography websites, has received criticism for facilitating and profiting from criminal acts including sex trafficking, filmed sexual abuse of children, and non- consensually recorded and distributed pornography.2 By investigating these criminal acts, the Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics has set an example of a commitment to the protection of the rights of some of the most vulnerable members of society, particularly children who are victims of or at risk of sexual abuse. As experts, survivors, and advocates combating sexual violence and exploitation, we found the February 5, 2021, testimonies of MindGeek executives Feras Antoon, David Tassillo and Corey Urman to the Committee notably egregious in their failure to take responsibility for the destruction of countless victims’ lives over the past decade.3 Antoon, Tassillo and Urman appeared to be obfuscating their current and historical business practices4 in the obtaining, distributing and advertising of child sexual abuse images,5 rape, trafficking6 and non-consensually recorded and/or distributed pornography.7 MindGeek executives appeared to mislead the Committee and the public regarding MindGeek’s role in enabling and profiting from a range of criminal content that was uploaded and distributed through their platform.8 Based on the evidence,9 including testimony of victims and the potentially criminally implicating testimony of MindGeek executives on February 5, it appears that MindGeek has violated 1 House of Commons Canada, “Meeting No. -

1 Au Comité Permanent De L'accès a L'information, De La Protection Des

Au Comité permanent de l’accès a l’information, de la protection des renseignements personnels et de l’éthique Protection de la vie privée et de la réputation sur les plateformes telle Pornhub Le 22 février, 2021 Nous félicitons le gouvernement canadien de s'être efforcé de tenir MindGeek responsable de la facilitation et d’avoir profité des abus et de l'exploitation sexuels.[1]MindGeek, propriétaire de Pornhub et au moins 160 autres sites Web de pornographie hardcore, a été critiqué pour avoir facilité et tiré profit d'actes criminels, y compris le trafic sexuel, l’abus sexuel filmé d'enfants, ainsi que de la pornographie enregistrée et distribuée sans consentement.1 En enquêtant sur ces actes criminels, le Comité permanent de l'accès à l'information, de la protection des renseignements personels et de l'éthique a donné l'exemple d'un engagement à protéger les droits de certains des membres les plus vulnérables de la société, en particulier les enfants victimes ou à risque d’abus sexuel. En tant qu'experts, survivants et défenseurs de la lutte contre la violence et l'exploitation sexuelles, nous avons trouvé les témoignages du 5 février 2021 des dirigeants de MindGeek Feras Antoon, David Tassillo et Corey Urman au Comité, particulièrement flagrants dans leur incapacité à assumer la responsabilité de la destruction de la vie d'innombrables victimes au cours de la dernière décennie.2 Antoon, Tassillo et Urman semblaient obscurcir leurs pratiques commerciales actuelles et historiques3 dans l'obtention, la distribution et la publication d'images d'abus pédosexuels,4 de viol, de trafic5 et de pornographie non consensuellement enregistrée et/ou distribuée.6 Les dirigeants de MindGeek ont semblé induire en erreur le Comité et le public en ce qui concerne le rôle de MindGeek en permettant et en tirant parti d'une gamme de contenus criminels téléchargés et distribués via leur plateforme.7 1 Nicholas Kristof, “The Children of Pornhub. -

Combating-Child-Sex-Tourism-English-1.Pdf

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The IBCR would like to thank… The members of our coalition One Child : http://onechild.ca/ Plan Canada : http://plancanada.ca/ UNICEF Canada : http://www.unicef.ca/ Our institutional partners The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), the Minister of Justice of Canada, Public Safety Canada, the SPVM (Service de police de la Ville de Montreal), the Surêté du Quebéc The private sector BCP advertising, Air Canada, Astral Media, Cybertip The Montreal International Airport authorities Our dedicated team of interns who worked on various stages of this 2 year long effort lead by Programme Manager, Marco Sotelo, and Director General, Nadja Pollaert: Anne-Marie Levesque, Marie Bernier, Mia Choinière, Caroline Rochon-Gruselle, Tina Iriotakis, Kristina Ziaugra, Marie-Luise Ermisch, Catherine Legault and Vienna Napier. Our deepest gratitude goes to the religious communities in Canada who believed from the beginning that the promotion of the extraterritorial law, the prevention of child sex tourism through the collaboration of key stakeholders and the prosecution of Canadians exploiting children abroad is a main concern. We are thankful to the Minister of Justice of Canada who generously contributed to promote the protection of children in 2011. Who is the International Bureau for Children’s Rights (IBCR)? The IBCR is an international nongovernmental organisation based in Montreal, Canada. Our mission is to contribute to the promotion and the respect of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), an international legal instrument adopted by the UN in 1989 and now ratified by 192 countries. It was the CRC that lead to the creation of the IBCR. -

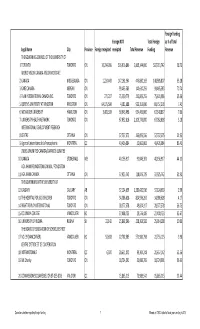

Canadian-Charities-Table-A.Pdf

Foreign Funding Foreign NOT Total Foreign as % of Total Legal Name City Province Foreign receipted receipted Total Revenue Funding Revenue THE GOVERNING COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF 1 TORONTO TORONTO ON 10,294,936 526,916,806 2,865,144,000 537,211,742 18.75 WORLD VISION CANADA‐VISION MONDIALE 2 CANADA MISSISSAUGA ON 1,224,443 147,161,364 445,830,169 148,385,807 33.28 3 CARE CANADA NEPEAN ON 99,465,583 140,610,259 99,465,583 70.74 4 PLAN INTERNATIONAL CANADA INC. TORONTO ON 271,207 75,330,779 213,809,255 75,601,986 35.36 5 QUEEN'S UNIVERSITY AT KINGSTON KINGSTON ON 64,175,590 4,581,688 923,353,036 68,757,278 7.45 6 MCMASTER UNIVERSITY HAMILTON ON 3,405,339 63,943,498 954,409,000 67,348,837 7.06 7 UNIVERSITY HEALTH NETWORK TORONTO ON 67,052,818 2,105,776,000 67,052,818 3.18 INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH 8 CENTRE OTTAWA ON 57,737,575 263,099,556 57,737,575 21.95 9 Agence Universitaire de la Francophonie MONTREAL QC 43,426,084 52,062,002 43,426,084 83.41 DUCKS UNLIMITED CANADA/CANARDS ILLIMITES 10 CANADA STONEWALL MB 40,156,917 91,046,301 40,156,917 44.11 AGA KHAN FOUNDATION CANADA / FONDATION 11 AGA KHAN CANADA OTTAWA ON 37,925,742 118,879,729 37,925,742 31.90 THE GOVERNORS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF 12 CALGARY CALGARY AB 37,124,639 1,280,420,916 37,124,639 2.90 13 THE HOSPITAL FOR SICK CHILDREN TORONTO ON 34,386,628 824,936,261 34,386,628 4.17 14 RIGHT TO PLAY INTERNATIONAL TORONTO ON 28,277,578 49,824,317 28,277,578 56.75 15 COLUMBIA COLLEGE VANCOUVER BC 27,408,723 29,576,489 27,408,723 92.67 16 UNIVERSITY OF REGINA REGINA SK 22,142 25,892,096 258,363,582 25,914,238 10.03 THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF SCHOOL DISTRICT 17 NO. -

Paper 1: an Automated Approach to Measuring Competitive Issue Framing at Scale

DRAFT An Automated Approach to Measuring Competitive Issue Framing at Scale Vincent Hopkins Mark Pickup Simon Fraser University Motivation Political groups frame issues to build support for their policy agenda. Issue framing helps unite diverse coalitions, but it may also invite competition from political opponents. Identifying political “discourse coalitions” – communities of allied interest groups that invoke similar semantic concepts during legislative debate (Hajer 1993) – is valuable but has proven not easily amenable to large-scale quantification. It involves identifying discursive concepts (“frames”), associating each frame with a political actor, and measuring the shared frames and other ties connecting those actors. The biggest scalability hurdle is reliance on human coders. The sheer amount of political debate – thousands of utterances between hundreds of actors over days, months or years – seems to demand a selection of a subset of the data for a small-N case study analysis. Similarly, the complexity of debate would appear to call for qualitative analysis. Indeed, the study of political discourse is perhaps best associated with the qualitative and post- modern traditions of social science (e.g. Hajer 1993, 1995; Schmidt 2008; Fischer 2012). Here, we propose a scalable, automated approach to identify discourse coalitions and measure the degree to which they compete over framing. Our approach builds off Leifeld and Haunss (2012), and combines web-scraping, topic modeling, and network analysis. First, we collect legislative committee debates and use unidimensional scaling to identify a political actor’s support (or opposition) for a given legislative proposal. Second, we use topic modeling to associate each actor with one or more issue frames. -

Extraterritorial Laws 1 Why They Are Not Really Working and How They Can Be Strengthened

EXTRATERRITORIAL LAWS 1 WHY THEY ARE NOT REALLY WORKING AND HOW THEY CAN BE STRENGTHENED SEPTEMBER 2008 2 Written by: Catherine Beaulieu Layout and Design by: Manida Naebklang September 2008 Copyright © ECPAT International ECPAT International 328/1 Phayathai Road Ratchathewi Bangkok 10400 THAILAND Tel: +662 215 3388, +662 611 0972 Fax: +662 215 8272 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ecpat.net TABLE OF conTENTS 3 EXTRATERRITORIAL LAWS: Why they are not really working and how they can be strengthened . 4 Extraterritorial legislation: a tool to fight child sex tourism . 5 Extraterritorial legislation regarding offences against children As implemented in selected examples of domestic jurisdiction . 8 Some obstacles to extraterritorial jurisdiction . 8 International cooperation and assistance . 13 Analysis and recommendations . 16 ENDNOTES . .19 EXTRATERRITORIAL LAWS: WHY THEY ARE NOT REALLY WORKING AND HOW THEY CAN BE STRENGTHENED The problem of child sex tourism was first brought to the world’s attention in the early 1990s largely as a result of the work of ECPAT and other non- governmental organisations (NGOs). The international community’s recognition and concern “at the widespread and continuing practice of sex tourism, to which children are especially vulnerable, as it directly promotes the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography” was also clearly stated in the preamble to the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography (OPSC)1. While a number of legally binding instruments currently impose obligations upon States to take measures to counter child sex tourism, the problem persists and continues to devastate the lives of countless children around the world, with often irreparable 4 consequences. -

A Question of Respect

A Question of Respect A Question of Respect: A Qualitative Text Analysis of the Canadian Parliamentary Committee Hearings on The Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act∗ Genevieve Fuji Johnson, Department of Political Science, Simon Fraser University Mary Burns, Department of Political Science, Simon Fraser University Kerry Porth, Independent Sex Worker Rights Educator, Researcher, and Writer This Accepted Manuscript will appear in a revised form, subsequent to editorial input, in the Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique (December 2017), published by Cambridge University Press. The authors have assigned full copyright of this manuscript to the Canadian Political Science Association (excluding the Methodological Appendix [Appendix B], which will be deposited in the Qualitative Data Repository [https://qdr.syr.edu/]). Abstract We evaluate the Canadian parliamentary hearings on The Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act to determine whether respectful and fair deliberation occurred. Our focus is on the content, tone, and nature of each question posed by committee members in hearings in both chambers. We find that, on the whole, the vast majority of questions met this baseline, but that committee members were biased toward witnesses in agreement with their position and against witnesses in opposition to it. In addition to our substantive findings, we contribute methodological insights, including a coding scheme, for this kind of qualitative text analysis. ∗ Esther Shannon provided the initial inspiration for this paper, and we would like to express our gratitude to her for planting the seed that led not only to this paper but also to its methodological appendix (deposited in the Qualitative Data Repository [https://qdr.syr.edu/]). -

Crime and Criminology Fifteenth Edition

Supplement to Accompany CRIME AND CRIMINOLOGY FIFTEENTH EDITION Sue Titus Reid Wolters Kluwer services its customers worldwide with CCH, Aspen Publishers, and Kluwer Law International products. See www.wolterskluerlb.com. This Supplement constitutes copyrighted material and is subject to United States Copyright laws. This Supplement is being made available as a courtesy to those teachers who have adopted the underlying textbook that accompanies the Supplement, as well as those teachers who have shown a genuine interest in adopting the underlying textbook. This may not be modified, reproduced, displayed, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the express, prior, written permission of Wolters Kluwer. Those teachers who have adopted the underlying textbook may assign this Supplement to their class and incorporate it into their class notes, presentation slides, and testing materials, or make certain other noncommercial uses of this Supplement as permitted by copyright law, but those teachers may not otherwise modify, reproduce, display, distribute, or transmit the manual in any form or by any means without the express prior written permission of Wolters Kluwer. For permission requests, visit us at www.wolterskluwerlb.com, or fax a written request to our permissions department at 212-771-0803. Table of Contents Chapter 1. Crime, Criminal Law, and Criminology .................................................................1 Supplement 1.1. Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Upholds Necessity Defense for Homeless